History

Crow Tribe

The Crow Tribe, also known as the Apsáalooke, is a Native American tribe historically located in the Yellowstone River valley. They are known for their nomadic lifestyle, skilled horsemanship, and distinctive beadwork and clothing. The Crow Tribe has a rich cultural heritage and has played a significant role in the history of the American West.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

3 Key excerpts on "Crow Tribe"

- eBook - ePub

Native American Bilingual Education

An Ethnography of Powerful Forces

- Cheryl K. Crawley(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Emerald Publishing Limited(Publisher)

The reservation today remains the central focus of life for the Crow people. All the major, minor, and familial social events that define Crow identity play out here. People congregate from long distances to attend important functions such as Sun Dance or Tobacco Society adoption, funerals, and children's powwows. They sew and wear colorful team outfits to compete in handgame tournament in the dead of winter. And, of course, people come from all over Indian Country to participate and compete at Crow Fair – that annual week-long extravaganza of camping in tepees, rodeoing, horse racing, parading, and long nights of dancing and drumming contests – to say nothing of youthful romance budding under the stars to the deep base of the drums, between teenagers including those from other tribes that visit from all parts of the pan-Indian powwow circuit.Stabilizing Forces

Several circumstances have set the Crow apart from the experiences of many American Indian tribes and have certainly influenced strong native language retention and provided a sense of socioemotional stability for their young people. One of these is that, despite the shrinking nature of the boundaries, they remain today on their ancestral lands. They have not experienced forced migration from a prior home to a vastly different ecological niche like the various tribes relocated from all over the United States onto reservations in Oklahoma. This fact also supports the power of the place-based myths and stories of the elders to retain impact as they are told to the young.Neither have the Crow experienced being combined on a single reservation with two other tribes that spoke entirely different languages as has been inflicted on the tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation in central Oregon or the Flathead Reservation in Western Montana, to name but two. It is no secret that this was federal Indian policy in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, “to divide and conquer,” and that it was designed and implemented with the intent to make it easier for the United States government to manage its “Indian problem.” - eBook - PDF

Radical Hope

Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation

- Jonathan Lear(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Harvard University Press(Publisher)

To survive as a nomadic tribe, they had to be good hunters, but they also had to be good at protect-ing themselves against rival tribes—notably the Sioux, the Black-feet, and the Cheyenne. Fighting battles, defending one’s ter-ritory, preparing to go to war—all this permeated the Crow way of life. The Crow were and are known to themselves as Absaro-kee, which literally means “children of the Large-Beaked Bird.” French trappers and traders took that bird to be a crow—and thus named the tribe Le Corbeau. It is generally thought that the Eu-ropeans misidentified the bird, though its exact identity remains uncertain. 10 Robert Lowie, an anthropologist who visited the Crow at the After This, Nothing Happened 11 turn of the twentieth century and recorded the memories of those who could remember the old way of life, described the situation this way: War was not the concern of a class nor even of the male sex, but of the whole population, from cradle to grave. Girls as well as boys derived their names from a famous man’s exploit. Women danced wearing scalps, derived honor from their husbands’ deeds, publicly exhibited the men’s shield or weapons; and a woman’s lamentations over a slain son was the most effective goad to a punitive expedition . . . Most characteristic was the intertwining of war and re-ligion. The Sun Dance, being a prayer for revenge, was naturally saturated with military episodes; but these were almost as prominent in the Tobacco ritual, whose avowed purpose was merely the general welfare. More significant still, every single military undertaking was theoretically inspired by a revelation in dream or vision; and since success in life was so largely a matter of mar-tial glory, war exploits became the chief content of prayer. 11 Training for war began in childhood. Apart from athletic games, the boys counted coups on game animals, made the girls dance with the hair of a wolf or coyote in lieu of a scalp . - eBook - ePub

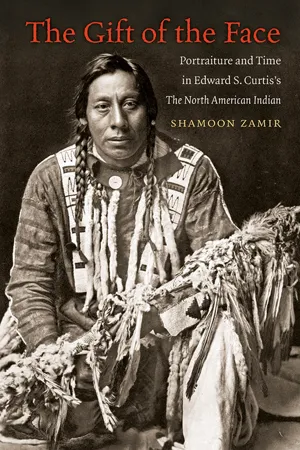

The Gift of the Face

Portraiture and Time in Edward S. Curtis's The North American Indian

- Shamoon Zamir(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- The University of North Carolina Press(Publisher)

A renewed assault on Crow land by Congress in 1906 led to the formation of complex and shifting alliances among older and younger Crow, among different Crow factions, and among the Crow and representatives of the white authorities. Tensions found a focus in grievances against the new tribal agent, Samuel G. Reynolds, and his supporters. A new men’s club, the Elk Lodge, was set up to offer support to Reynolds, and all agency employees, including Upshaw, were members (Hoxie 244). But the aims and motivations of membership in the Elk Lodge were not defined by obedience to the agendas of the reservation administration. The high regard in which Upshaw was held by his fellow Crow and the animosity toward him from local whites makes it clear that he was no lackey of the authorities. Carl Leider, one of the committed new leaders and a supporter of Plenty Coups, was also a member of the lodge, even though Plenty Coups himself was at that time associated with the rival Crow Indian Lodge. Older leaders such as Two Leggings were also members. The conflicts between the lodges or between tribal members and reservation authorities cannot therefore be characterized simplistically through oppositions between one generation and another, or between Crows and whites, or between assimilationists and traditionalists. Rather, they reflected complex debates and struggles among the Crow about their future welfare and survival. By 1908 a more enduring and effective consensus had emerged and old leaders like Plenty Coups, who had become tribal chief in 1904, and the younger generation of men like Upshaw had come together to form something that began to resemble a representative tribal government that accepted cultural and social change but also sought to mold the process of transformation to Crow needs and to a Crow sense of identity.Curtis’s project offered the Crow the first systematic and wide-ranging ethnographic and visual survey of their traditional culture at a time when the tribe faced unprecedented crisis. A million acres of the 3.4 million acres of collectively owned tribal land were lost in 1904 and further losses followed (Hoxie 269). The population, never large, had dropped dramatically from about 3,500 in 1880 to well under 2,000 in 1900, and it continued to decline during the years in which Curtis and his team worked among the Crow (Hoxie 172). During the same years many traditional cultural practices and institutions atrophied, were banned by agency authorities, or were radically transformed by the arrival of either Christian missionaries and educators or of new Native cultural forms such as the Peyote cult (Hoxie chap. 7). This was the context in which the Crow and Upshaw considered the invitation to participate in the making of The North American Indian

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.