History

Ojibwe

Ojibwe is a Native American tribe that originally inhabited the Great Lakes region of North America. They were known for their hunting, fishing, and gathering practices, as well as their use of birch bark canoes and wigwams. The Ojibwe were also known for their oral traditions and storytelling.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

6 Key excerpts on "Ojibwe"

- eBook - PDF

Women's Rights

A Global View

- Lynn Walter(Author)

- 2000(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

As tribal people were introduced to and, in many cases, forced to accept Western culture, the subordinate, disempowered social, economic, and political position of Western women became a reality for many Indian women. This chapter explores the impact of colonization on the rights of Ojibwe women in the western Great Lakes region of the United States. Like other American Indian nations, traditionally the Ojibwe placed pri- mary emphasis on the community over that of individuals and subgroups within the Nation. The primacy of community remains an important cultural value today for Ojibwe people. Thus, an examination of Ojibwe women's rights can only be explored within the larger framework of understanding the historical and contemporary experiences of the Ojibwe Nation as a whole. One cannot isolate the experiences of Ojibwe women from the ex- periences of the Nation as a collective. Thus, throughout this chapter, Ojibwe women's rights will be explored as the combined experiences of the Nation. In precontact Ojibwe society, women were central figures in the cosmol- ogy of the Nation. The significance of Ojibwe women within traditional tribal spiritual beliefs was further reflected within the daily life of the Nation. While Ojibwe women and men often performed separate and distinct gender roles and duties within their communities, those of the women were held in high regard and were not viewed as inferior to those of the men. Balanced roles and relationships between Ojibwe women and men were a reality because human beings were viewed in terms of their shared differ- ences from and similarities with each other, as well as with other living beings. Perceived differences between humans, including differences in bi- ological sex, were viewed in terms of how those variations reflected each other. Such differences were viewed as symmetrical, or as mirroring each other in metaphysical balance. - eBook - PDF

'You're So Fat!'

Exploring Ojibwe Discourse

- Roger Spielmann(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- University of Toronto Press(Publisher)

1 The next question we want to tackle is: What are some of the distinc-tive features of Ojibwe that differentiate it from Indo-European lan-guages such as English and French? As a corollary to that, we will explore what the relationship is between knowing one's Aboriginal lan-guage and one's sense of identity. Linguistic Concepts and Cultural Differences Some of the more glaring examples of cultural differences which lead to tension in Native/non-Native interaction have to do with language dif-ferences. Ojibwe is a very rich and complex language and even minor changes in the pronunciation (or spelling) can completely change the meaning of a word. When I was first learning the language I remember standing with some of the elders watching a hockey game. At one point, one of them turned to me and politely asked 'Gigaawajinan naa?' which means 'Are you cold?' I wanted to answer her with a nifty phrase that I had learned recently from another elder, 'Ehe, nigichi maashkaawidiye,' which means 'Yes, my ass is frozen!' But I forgot the exact phrase and what came out of my mouth was, 'Ehe, nigichi minokwidiye,' which Language as a Window on a People 45 means 'Yes, I have a really nice ass.' The elder immediately went into fits of laughter and turned to her friends and said, 'I asked him if he was cold and he says he has a real nice ass!' Only then did I realize my mis-take. People still remind me of that incident years later. Ojibwe belongs to the great Algonquian family of languages in North America. Other Algonquian languages include Cree, Algonquin, Mon-tagnais, Atikamekw, Blackfoot, Kickapoo, and Micmac, to name but a few. Like many North American Indian languages, the verb is the heart of the language. Ojibwe has a complex set of prefixes and suffixes that can be attached to words to indicate all sorts of things. Also, word order within sentences is much freer than in English. - eBook - PDF

- A. Irving Hallowell(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

16 Prior to the conclusion of treaties with the Ojibwa and their assign-ment to reservations (in the United States not until after the War of 1812 and in Western Canada subsequently to the establishment of the Dominion Government in 1867), they had undergone an enormous ter-117 II. WORLD VIEW, PERSONALITY STRUCTURE, AND THE SELF: ritorial expansion. This was roughly concomitant with the spread of the fur trade in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In what became the states of Wisconsin and Minnesota they had first displaced the Fox and then the Sioux by the middle of the eighteenth century. About the same time and later, many of the Canadian Ojibwa began to move closer to Hudson Bay and westward to the region of Lake Winni-peg and beyond. As early as 1794 Ojibwa were to be found near the Pas and even a considerable distance farther up the Saskatchewan River. Some of them, coming under the cultural influence of the Assiniboine with whom they came into contact on the northern Canadian prairie adjacent to the coniferous forest and poplar parkland, later became known as the Plains Ojibwa. Most of the Ojibwa, however, did not stray outside the northern coniferous forest belt, the region in which their aboriginal hunting, fishing, and gathering culture is so thoroughly rooted. In broad terms, their native culture is essentially a variant of that characteristic of other northern peoples of Algonkian lineage whose habitat in the aboriginal period, as now, was the Eastern Sub-Arctic and the Northern Great Lakes. 17 The ancestors of the Berens River Indians were, then, among the western Ojibwa migrants, a fact for which I have abundant evidence in extensive genealogical data. - eBook - ePub

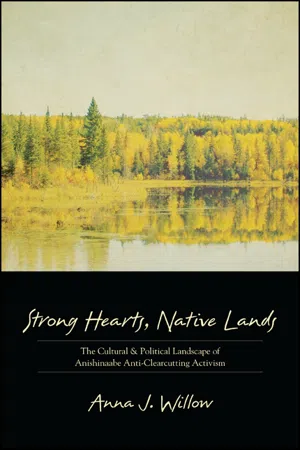

Strong Hearts, Native Lands

The Cultural and Political Landscape of Anishinaabe Anti-Clearcutting Activism

- Anna J. Willow(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- SUNY Press(Publisher)

Furthermore, other societies rarely share the Western fixation with uncovering or proving “objective” historical facts and linear sequences of events (Sahlins 1985 ; Comaroff and Comaroff 1992). Rather than searching for a factual picture of the past, non-Western peoples' understandings of historical truth—as remembered through stories, landmarks, art, and numerous other mnemonic techniques—have more often involved translating past events to fit contemporary circumstances and meanings. In this context, oral history may be best seen “not as ‘evidence’ about the past but as a window on ways the past is culturally constituted and discussed” (Cruikshank 1990: 14). Rather than relegating history to the forgotten past, oral societies have found ways to keep it living and relevant. As Anishinaabe scholar Gerald Vizenor (1984: 24) poetically expounds, The Anishinaabeg did not have written histories; their world views were not linear narratives that started and stopped in manifest barriers. The tribal past lived as an event in visual memories and oratorical gestures; woodland identities turned on dreams and visions. The historical consciousness Vizenor describes continues to inform how Anishinaabe people contemplate their own histories and how they make sense of the intersections between their own views of the past and those held by others. Generally speaking, Anishinaabe and Western historical traditions agree that the people now occupying the Northwestern Great Lakes region have origins in more easterly parts of North America. The group of people today known interchangeably as Anishinaabe, Ojibwe, and Chippewa—together with closely related groups like the Potawatomi and Ottawa/Odawa—migrated from an eastern land of salt water, most probably near the mouth of the St. Lawrence River. Assigning a precise date to the commencement or completion of their westward journey remains impossible and, in any case, the movement did not occur all at once - eBook - ePub

American Nations

Encounters in Indian Country, 1850 to the Present

- Frederick Hoxie, Peter Mancall, James Merrell(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

American Indian Stories (Washington, D.C.: Hayworth Publishing, 1921; rpt. Glorieta, N.M.: The Rio Grande Press, 1976), pp. 44-45.- 2. Ibid., pp. 40-41.

- 3. The Ojibwa (also known as Chippewa) are Algonquian-speaking peoples in the western Great Lakes region, southern Ontario, and Manitoba. During the nineteenth century most groups still retained a seasonal nomadism based on hunting and gathering, combined with occasional horticulture in the southern groups. For cultural and historical descriptions, see Frances Densmore, Chippewa Customs, Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 86 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1929); A. Irving Hallowell, Culture and Experience (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1955); Harold Hickerson, “The Chippewa of the Upper Great Lakes: A Study in Sociopolitical Change,” in Eleanor Burke Leacock and Nancy Oestreich Lurie, eds., North American Indians in Historical Perspective (New York: Random House, 1971), pp. 169-99.

- The people generally known to outsiders by the misnomer “Sioux” (a French mispronunciation of a derogatory Algonquian term meaning “little adders”) consist of seven linguistic and political subgroups, or “Fireplaces.” The eastern groups call themselves “Dakota,” while the western dialect pronounces that name “Lakota.” Before the reservation era they were seminomadic hunter-gatherers who followed the buffalo. See Roy W. Meyer, History of the Santee Sioux: United States Indian Policy on Trial (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1967); Marla N. Powers, Oglala Women: Myth, Ritual, and Reality (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986).

- 4. The last two decades have seen a significant growth in the written history of mission and government schools and Native American children’s experiences in them. See, for example, Robert F. Berkhofer, Jr., Salvation and the Savage: An Analysis of Protestant Missions and American Indian Response, 1787-1862, 2d. ed. (New York: Atheneum, 1976); Henry Warner Bowden, American Indians and Christian Missions: Studies in Conflict (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981); Mary Lou Hultgren and Paulette Fairbanks Molin, To Lead and to Serve: American Indian Education at Hampton Institute, 1878-1923 (Virginia Beach: Virginia Foundation for the Humanities and Public Policy, 1989); Elizabeth Muir, “The Bark School House: Methodist Episcopal Missionary Women in Upper Canada, 1827-1833,” in John S. Moir and C. T. Mclntire, eds., Canadian Protestant and Catholic Missions, 1820s-l960s: Historical Essays in Honor of John Webster Grant

- eBook - ePub

Tribal Worlds

Critical Studies in American Indian Nation Building

- Brian Hosmer, Larry Nesper, Brian Hosmer, Larry Nesper(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- SUNY Press(Publisher)

I have chosen to use “Anishinaabe” as it is the name used by the people themselves and adheres to contemporary scholarly practice. In addition, “Anishinaabe” connotes a broader group than some of these aforementioned terms are associated with. As I hope this article indicates, Anishinaabe conceptions of nationhood are complex and multifarious and involved extensive relationships across nations. Thus, while my focus is primarily on those people who refer to themselves as “Ojibwe” I use the more inclusive category of “Anishinaabe” to recognize the broader peoples discussed within this study. For a list of the various spellings and meanings associated with the Anishinaabe people, see E. S. Rogers, “Southeastern Ojibwa,” in Handbook of the North American Indians; Northeast, ed. Bruce G. Trigger (Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1996); Robert E. Ritzenthaler, “Southwestern Chippewa,” in Handbook of the North American Indians; Northeast, ed. Bruce G. Trigger (Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1996). 9. The English translation of jiibayag niimi'idiwag is “they are the northern lights.” See Nichols and Nyholm, A Concise Dictionary of Minnesota Ojibwe : 73. 10. See Frances Densmore and Smithsonian Institution. Bureau of American Ethnology., Chippewa customs, Reprint ed., Publications of the Minnesota Historical Society. (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1979), 74. For information on the paths of souls, see Basil Johnston, Ojibway Heritage (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1976), 103–8. 11. While there is no etymological connection between ishkode and the morpheme – ode ' within the linguistic method, folk etymologies (the stories told by speakers based on perceived resemblances and connections) have made this connection. 12. “Home” is used here to mean the land of the deceased. 13. For further discussion of the importance of tobacco and offerings, see A. Irving Hallowell, Culture and Experience, ed

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.