History

Cubism

Cubism was an influential art movement pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in the early 20th century. It revolutionized traditional artistic representation by depicting subjects from multiple viewpoints simultaneously, breaking them down into geometric shapes and forms. This approach challenged the conventions of perspective and representation, laying the groundwork for abstract art and influencing a wide range of artistic disciplines.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Cubism"

- eBook - PDF

Gardner's Art through the Ages

A Global History, Volume II

- Fred Kleiner(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

Cubism represented a radical turning point in the history of art, nothing less than a dismissal of the pictorial illusionism that had dominated Western art since the Renaissance. The Cubists rejected naturalistic depictions, preferring compositions of shapes and forms abstracted from the conventionally perceived world. As Picasso once explained: “I paint forms as I think them, not as I see them.” 5 Together, Picasso and Braque pursued the analysis of form central to Cézanne’s artistic explorations (see “Paul Cézanne,” page 868) by deconstructing objects and people into their constitu- ent parts, and then recomposing them by a new logic of design into a coherent, independent aesthetic picture. The Cubists’ rejection of accepted artistic practice illustrates both the period’s avant-garde critique of pictorial convention and the artists’ dwindling faith in a safe, concrete Newtonian world in the face of the physics of Ein- stein and others (see “Science and Art,” page 893). The new style received its name after Matisse described some of Braque’s work to the critic Louis Vauxcelles as having been painted “with little cubes.” In his review, Vauxcelles described the new paintings as “cubic oddities.” 6 The French writer and theorist Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918) summarized well the central concepts of Cubism in 1913: Authentic Cubism [is] the art of depicting new wholes with formal elements borrowed not from the reality of vision, but from that of con- ception. This tendency leads to a poetic kind of painting which stands outside the world of observation; for, even in a simple Cubism, the geometrical surfaces of an object must be opened out in order to give a complete representation of it. . . . Everyone must agree that a chair, from whichever side it is viewed, never ceases to have four legs, a seat and a back, and that, if it is robbed of one of these elements, it is robbed of an important part. - eBook - PDF

Econ-Art

Divorcing Art From Science in Modern Economics

- Rick Szostak(Author)

- 1999(Publication Date)

- Pluto Press(Publisher)

3 Cubism and More 3.1 Cubism As revolutionary as the discoveries of Einstein or Freud, the discoveries of Cubism controverted principles that had prevailed for centuries. (Rosenblum 1976, p. 13) One need not look far in order to find evidence of the importance of Cubism as a movement within twentieth-century art. Arnason (1986) feels that Cubism was the most revolutionary change since the Renaissance, and it became the ‘lingua franca’ of modern art for half a century. Golding (1988) concurs in this revolutionary judgement, and notes that the effects are still with us. Rubin also views the rise of Cubism as a seminal event, ‘from which gradu-ally emerged nothing less than a visual dialectic for twentieth century art’ (1989, p. 15). As mentioned in the previous chapter, Cubism pre-dates Surrealism by decades. Between 1908 and 1913, the collabora-tion of Picasso and Braque yielded an art form of breathtaking novelty. They were soon joined by a number of other talented artists. As the name Cubism implies, the artists rendered their subjects in terms of basic geometrical shapes. Freed from the constraints of trying to paint what the eye sees (a motive which had inspired the post-Impressionists and others from the late nineteenth century), the Cubists were able to represent more than one view of an object (for example, front and profile) on the same canvas. This, they argued, could provide a ‘truer’ depiction than a hyper-realistic portrayal from only one angle. Juan Gris, who joined the Cubists in 1913, viewed Cubism as, at the beginning, ‘simply a new way of representing the world’, a reaction against Impressionism. Cubists wanted to do more than examine ‘the momentary effects of light’. Indeed, early Cubist works, devoted to the exploration of the potentials of geometry, used a very limited range of colours, though by 1912 Cubists such - eBook - PDF

- Lois Fichner-Rathus(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

Analytic Cubism The term Cubism , like so many others, was coined by a hostile critic. In this case, the critic was responding to the predominance of geometrical forms in the works of Picasso and Braque. Cubism is a limited term in that it does not adequately describe the appearance of Cubist paintings, and it minimizes the intensity with which Cubist artists analyzed their subject matter. It ignores their most significant contribution—a new treatment of pictorial space that hinged upon the rendering of objects from multiple and radically different views. The Cubist treatment of space differed significantly from that in use since the Renaissance. Instead of pre-senting an object from a single view, assumed to have been the complete view, the Cubists, like Cézanne, real-ized that our visual comprehension of objects consists of many views that we perceive almost at once. They tried to render this visual “information gathering” in their compositions. In their dissection and reconstruction of imagery, they reassessed the notion that painting should reproduce the appearance of reality. Now the very real-ity of appearances was being questioned. To Cubists, Copyright 2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 468 | CHAPTER 20 The Twentieth Century: The Early Years perceptible triangular human figure, which is alternately constructed from and dissolved into the background. There are only a few concrete signs of its substance: dropped eyelids, a mustache, the circular opening of a stringed instrument. - eBook - ePub

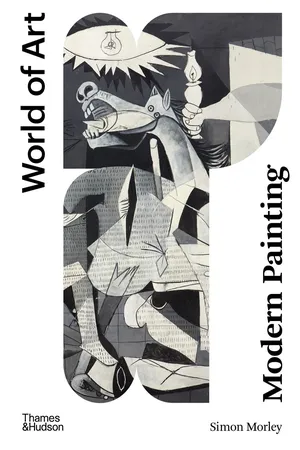

Modern Painting

A Concise History

- Simon Morley(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Thames and Hudson Ltd(Publisher)

Around the same time that Kandinsky was tentatively pushing towards the ‘spiritual’, ‘abstraction’ was being pursued in Paris with very different goals in mind. The style that became known as Cubism began to emerge as a recognizable tendency in 1907 and initially entailed ‘abstracting’ in the older sense of the term – extracting, removing or simplifying selected elements from an external referent. Cubist works made by such artists as Georges Braque, Albert Gleizes, Juan Gris, Fernand Léger and, most famously, Pablo Picasso signalled a shift in painting towards balancing the inner world of the imagination and thought and the outer world of observation and experience.In their quest for an art that was geared less overtly towards self-expression and more to the measured analysis of the visible, in the period 1910 to 1912 the works of the two pioneers of Cubism, Braque (1882–1963) and Picasso (1881–1973), became almost indistinguishable, and were characterized by the selection of an unprepossessing subject – for example, a nude figure or still-life – which was then painted as if observed from multiple viewpoints and reconstructed using faceted or linear ‘cube-like’ or gridded forms. The works were also primarily painted in an almost monochromatic palette of black, grey and muted ochres, so an all-over, homogenous surface was produced. Often, Cubist artworks substituted an abstract sign for an image based on pictorial resemblance. Rather than using perspective and modelling or simulating an ‘impression’ of a visual stimulus, thereby producing a representation of a static theme as seen from a particular point of view, a Cubist painting introduced the movements involved in scanning the visual field that are part of normal vision. It also relied far more than was usually the case in painting based on observation on the memory of what things look like, on a repertoire of repeated visual units designating familiar objects. This was a new kind of pictorial script or visual code that had to be learned, like writing. But it was also a reminder that all paintings – however seemingly ‘natural’ or ‘realistic’ – rely on a code that must be learned. - No longer available |Learn more

Gardner's Art through the Ages

A Global History, Volume II

- Fred Kleiner(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

One of the first to see it was Georges Braque (1882–1963), a Fauve painter who found it so challenging that he began to rethink his own painting style. Using the painting’s revolutionary elements as a point of departure, together Braque and Picasso formulated Cubism around 1908 in the belief that the art of painting had to move far beyond the descrip-tion of visual reality. Cubism represented a radical turning point in the history of art, nothing less than a dismissal of the pictorial illu-sionism that had dominated Western art since the Renaissance. The Cubists rejected naturalistic depictions, preferring compositions of shapes and forms abstracted from the conventionally perceived world. As Picasso once explained: “I paint forms as I think them, not as I see them.” 5 Together, Picasso and Braque pursued the analy-sis of form central to Cézanne’s artistic explorations (see page 860 and figs. 28-22 to 28-23A) by dissecting everything around them into its many constituent features, which they then recomposed, by a new logic of design, into a coherent, independent aesthetic pic-ture. The Cubists’ rejection of accepted artistic practice illustrates both the period’s avant-garde critique of pictorial convention and the artists’ dwindling faith in a safe, concrete Newtonian world in the face of the physics of Einstein and others (see “Science and Art,” page 887). The new style received its name after Matisse described some of Braque’s work to the critic Louis Vauxcelles as having been painted “with little cubes.” In his review, Vauxcelles described the new paint-ings as “cubic oddities.” 6 The French writer and theorist Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918) summarized well the central concepts of Cubism in 1913: Authentic Cubism [is] the art of depicting new wholes with formal elements borrowed not from the reality of vision, but from that of con-ception. - eBook - PDF

Gardner's Art through the Ages

A Concise Western History

- Fred Kleiner(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

One of the first to see it was Georges Braque (1882–1963), a Fauve painter who found it so challenging that he began to rethink his own painting style. Using the painting’s revolutionary elements as a point of departure, together Braque and Picasso formulated Cubism around 1908 in the belief that the art of painting had to move far beyond the descrip- tion of visual reality. Cubism represented a radical turning point in the history of art, nothing less than a dismissal of the pictorial illu- sionism that had dominated Western art since the Renaissance. The Cubists rejected naturalistic depictions, preferring compositions of shapes and forms abstracted from the conventionally perceived world. As Picasso once explained: “I paint forms as I think them, not as I see them.” 4 Together, Picasso and Braque pursued the analy- sis of form central to Cézanne’s artistic explorations (see “Making Impressionism Solid and Enduring,” page 369) by dissecting every- thing around them into their many constituent features, which they then recomposed, by a new logic of design, into a coherent, inde- pendent aesthetic picture. The new style received its name after Matisse described some of Braque’s work to the critic Louis Vauxcelles as having been painted “with little cubes.” In his review, Vauxcelles described the new paint- ings as “cubic oddities.” 5 The French writer and theorist Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918) summarized well the central concepts of Cubism in 1913: Authentic Cubism [is] the art of depicting new wholes with formal elements borrowed not from the reality of vision, but from that of con- ception. This tendency leads to a poetic kind of painting which stands outside the world of observation; for, even in a simple Cubism, the geometrical surfaces of an object must be opened out in order to give a complete representation of it. - eBook - PDF

Gardner's Art through the Ages

A Concise Global History

- Fred Kleiner(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

One of the first to see it was Georges Braque (1882–1963), a Fauve painter who found it so challenging that he began to rethink his own painting style. Using the painting’s revolutionary elements as a point of departure, together Braque and Picasso formulated Cubism around 1908 in the belief that the art of painting had to move far beyond the descrip-tion of visual reality. Cubism represented a radical turning point in the history of art, nothing less than a dismissal of the pictorial illu-sionism that had dominated Western art since the Renaissance. The Cubists rejected naturalistic depictions, preferring compositions of shapes and forms abstracted from the conventionally perceived world. As Picasso once explained: “I paint forms as I think them, not as I see them.” 4 Together, Picasso and Braque pursued the analy-sis of form central to Cézanne’s artistic explorations (see “Making Impressionism Solid and Enduring,” page 369) by dissecting every-thing around them into their many constituent features, which they then recomposed, by a new logic of design, into a coherent, inde-pendent aesthetic picture. The new style received its name after Matisse described some of Braque’s work to the critic Louis Vauxcelles as having been painted “with little cubes.” In his review, Vauxcelles described the new paint-ings as “cubic oddities.” 5 The French writer and theorist Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918) summarized well the central concepts of Cubism in 1913: Authentic Cubism [is] the art of depicting new wholes with formal elements borrowed not from the reality of vision, but from that of con-ception. This tendency leads to a poetic kind of painting which stands outside the world of observation; for, even in a simple Cubism, the geometrical surfaces of an object must be opened out in order to give a complete representation of it. - eBook - PDF

- May Spangler(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

With the use of perspective, Renaissance artists introduced a third dimension—depth—that gave an illusion of reality; five centuries later, Cubism takes on the challenge of representing a fourth dimension—time—and along with it the dynamic way modern man expe- riences space. Cubism and Modern Architecture in Paris | 301 Fig. 8.1. Sauvage, Rue des Amiraux, 1922. Section through pool. Fig. 8.2. Mallet-Stevens, Villa Martel on Rue Mallet-Stevens, 1927. Fig. 8.3. Boileau, Carlu and Azéma, Palais de Chaillot, 1937. 302 | Paris in Architecture, Literature, and Art Cubism is taken here as a generic name for artistic, literary and architectural productions between 1907 and the late 1920s that conceive art as a ground for conceptual experimentation. In painting, Cubism introduces the movement of time by multiplying perspectival points and light sources. Pablo Picasso’s Por- trait of Ambroise Vollard presents a series of intersecting geometric planes, with a transparent quality that make the image look like shattered glass. It is as if the “breaking away” from traditional Renaissance representation had been literal, and Alberti’s Della pittura window set-up had its transparent glass panes smashed into pieces. The intersecting planes also bring a new conception of boundaries, which rather than separating objects, become a place of interaction between figures and environment, solid and void, foreground and background. This confusion brings the beholder into the cubist realm of ambiguous interpretations. A freeing from conventions is apparent in literature as well. Guillaume Apollinaire, poet, art critic and friend of the cubist artists, has a leading role in defending and publicizing Cubism. In his poem Windows, the traditional illu- sion of a narrative centered on a subjective “I” gives place to a multiplication of personal pronouns much like the cubist multiplication of perspective points. - eBook - PDF

Culture and Values

A Survey of the Humanities, Volume II

- Lawrence Cunningham, John Reich, Lois Fichner-Rathus, , Lawrence Cunningham, John Reich, Lois Fichner-Rathus(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

The 2. Stein is said to have penned a new genre of literature—writing another person’s autobiography. thick-lidded eyes stare stage front, calling to mind some of the Mesopotamian votive sculptures we saw in Chapter 1. The bodies of the women are fractured into geometric forms and set before a background of similarly splintered drap- ery. In treating the background and the foreground imagery in the same manner, Picasso collapses the space between the planes and asserts the two-dimensionality of the canvas surface in the manner of Cézanne. In some radical passages, such as the right leg of the leftmost figure, the limb takes on the qualities of drapery, masking the distinction between figure and ground. The extreme faceting of form, the use of multiple views, and the collapsing of space in Les Demoiselles together provided the springboard for Analytic Cubism, cofounded with the French painter Georges Braque in about 1910. ANALYTIC Cubism The term Cubism, like so many oth- ers, was coined by a hostile critic. In this case, the critic was responding to the predominance of geometrical forms in the works of Picasso and Braque. Cubism is a limited term in that it does not adequately describe the appearance of Cubist paint- ings, and it minimizes the intensity with which Cubist artists analyzed their subject matter. It ignores their most significant contribution—a new treatment of pictorial space that hinged upon the rendering of objects from multiple and radically dif- ferent views. The Cubist treatment of space differed significantly from that in use since the Renaissance. Instead of presenting an object from a single view, assumed to have been the complete view, the Cubists—as did Cézanne—realized that our visual comprehen- sion of objects consists of many views that we perceive almost at once. They tried to render this visual “information gathering” in their compositions. - eBook - PDF

- Ian Heywood, Barry Sandywell, Ian Heywood, Barry Sandywell(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Academic(Publisher)

210 ART AND VISUALITY on the belief that painting as an art could refer to, and make something of value from, a common human experience of life, via some kind of metaphoric transformation of ordinary visual appearances. The difficulty is coming to terms with how this works out in practice. Poggi accurately describes these works as composed of contrasts, a ‘play of differen-tiated signifiers: the straight edged versus the curved, the modelled versus the flat, the transparent versus the opaque, the handcrafted versus the machine-made, the literal ver-sus the figurative’ (1992: 78). She claims that Braque and Picasso are practically propos-ing ‘the artificiality of art and the arbitrary, diacritical nature of its signs’ (78). The basic argument is as follows: the whole tradition of painting as an art is about illusion; Cub-ism is sophisticated, self-aware art that rigorously rejects mimesis (while toying with the devices upon which it depends); hence Cubism negates, or is ironical about, painting as an art. Put in poststructuralist terms, Cubism rejects the task of imitating the look of the ‘organic object’, the solid, opaque, self-identical object available for imitation, in fa-vour of a collection of discrete formal units, a bit like letters or words. These units may be combined to create the effect of reference or meaning, but in this case at least, do not tell us anything substantial or new, even by way of metaphor, through the look of the objects they allude to. Indeed, by employing these elements in paradoxical and con-tradictory ways Braque and Picasso do not give the viewer more information about the visible world but seek to ‘undermine the traditional conventions of illusion by isolating them and setting them in opposition’ (Poggi 1992: 46). - eBook - PDF

- Jesse Bryant Wilder(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- For Dummies(Publisher)

Einstein also proved that energy and matter are essentially the same thing. The Futurists capitalized on this idea by merging motion (energy) and matter in their art. Cubism: All Views At Once What is Cubism? Crack an egg and reassemble its fragments on a flat surface. Voilà, you’ve made a kind of Cubist construction. You can see all sides of the egg at once, and yet it’s hard to recognize the egg (or cook with it!). 330 PART 5 Twentieth and Twenty-First Century Art Cubist artists moved art toward abstraction by breaking down physical reality into geomet-ric shapes, usually cubes, and then rearranging the cubes — often independently of what they represent — on a flat surface with little or no perspective. A Cubist painting lets you see an object from multiple viewpoints simultaneously, although you might not recognize the object. Cubists didn’t just fragment the main subject of their paintings (the egg) — they also shat -tered the background (the frying pan, refrigerator, or kitchen). When they reconstructed the fragments, they often mixed the subject and background so that these physical ele-ments interpenetrate one another. In other words, if you shattered both the egg and the frying pan, when you reconstructed them, you might put the frying pan in the egg instead of the egg in the frying pan. The founders of Cubism were Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso. The first fully Cubist painting is Braque’s Houses at L’Estaque. The cluster of cubelike houses in the painting looks like a rockslide on a steep slope. The painting has almost no depth; the background houses are simply the top of the rockslide. Other Cubists include Juan Gris, Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, and Marie Laurencin, until her style changed in the 1920s. Pablo Picasso The art of Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) dominates much of the 20th century, probably because it kept pace with progress — or stayed a few steps ahead of it. - eBook - PDF

- Richard Lewis, Susan Lewis(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

To study their new structure, Picasso and Braque initially limited color in their work, a style called Analytical Cubism . The first Analytical Cubist pictures are a collection of views from different angles fused into a balanced design. Like Cézanne, they wanted to present a truer picture of the way we see, with eyes moving from one part to another. But as Picasso and Braque further explored Cubism, their work became more and more abstract; the arrange-ment of shapes became less like the source objects (see Braque’s Violin and Palette , 3-26), and the design of the many shapes in the picture became more important than any representational function. Picasso and Braque had created a new reality, one that existed only in the painting. Picasso declared that a picture should “live its own life.” The Cubists were posing once more the crucial question of Modern Art: Should art be chained to visual appearances? Their answer, as seen in their works, is a loud “no!” Art can give us experiences that reality cannot, they would say. It is time for the art-ist to be liberated from the old requirement of recreating what anyone can see. While much of the public remained horrified by Cubist pictures, Cubism spread like wildfire in the next few years through the avant-garde in Europe and beyond. Yet by 1912, Picasso wanted to find a way to bring the real world more directly into Cubist pictures. He did it by literally attaching bits and pieces from everyday life— inventing collage (see Chapter 5). The first was Still Life with Chair-Caning ( 18-12 ), where Cubist painting is mixed with a printed pattern of chair caning on it. Picasso used collage to play fast and loose with visual reality, to ques-tion its nature. In the picture, some letters from the French paper Le Journal appear as simulated collage, but they were actually painted on the canvas. This kind of decep-tion forced viewers to examine his art closely, because one cannot always be sure what is paint and what is collage.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.