History

Fair Housing Act 1968

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 is a landmark federal law in the United States that prohibits discrimination in the sale, rental, and financing of housing based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. It was enacted as part of the Civil Rights Act and aimed to address housing discrimination and segregation, promoting fair and equal access to housing opportunities for all.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Fair Housing Act 1968"

- Marcus D. Pohlmann, Linda Vallar Whisenhunt(Authors)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

Individuals had to file suit themselves and then had the burden of proof, even though such discrimination is often subtle and hard to pinpoint. Fair housing groups attempted to help, but little actually changed as a result of this original law. The 1988 Fair Housing Amendments Act strengthened enforcement proce- dures and allowed the Department of Housing and Urban Devel- opment to initiate legal action. Nonetheless, most U.S. cities remained heavily segregated by race. 19 THE LAW Titles VIII and IX of the 1968 Civil Rights of Act, 20 commonly referred to as the Fair Housing Act, barred discriminatory practices in the advertising, sale, rental, or financing of most dwellings. The act specifically prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, or national origin. Injuring, intimidating, or interfering with individuals attempting to exercise rights to fair housing was specifically prohibited by the act and punishable by fines and im- prisonment. 21 Authority for administration of the Fair Housing Act was given to the secretary of housing and urban development, who was also charged with the responsibility of commencing educational and co- operative activities to further the purposes of the act. The secretary was encouraged to cooperate with state and local agencies involved in the administration of fair housing laws. Executive departments and agencies of the Federal government were directed to admin- ister their housing-related programs in accordance with the act and to cooperate with the secretary. The enforcement provisions of the Fair Housing Act required individuals to file a written complaint with the secretary. Upon re- ceipt of the complaint, the secretary was required to investigate and 266 CIVIL RIGHTS ERA determine whether to attempt to resolve the dispute.- eBook - ePub

- Vincent J. Reina, Wendell E. Pritchett, Susan M. Wachter, Vincent J. Reina, Wendell E. Pritchett, Susan M. Wachter(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- University of Pennsylvania Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER 1 The Long History of Unfair Housing Francesca Russello Ammon and Wendell E. PritchettIntroductionWhen Congress passed the Fair Housing Act of 1968, it was responding most immediately to the civil rights and housing crises of that era. But the roots of this policy reach much further back in time to encompass a long history of housing discrimination and segregation. This chapter traces the federal policies, professional practices, legal decisions, and local actions, from the end of Reconstruction through passage of the Fair Housing Act, through which people of color and African Americans in particular have experienced unequal access to affordable housing and homeownership. This is a story of individual choices grounded in larger structural forces that have shaped the legal, economic, and practical accessibility of indiscriminately available and integrated housing through the postwar decades.Following World War II, the issues of housing discrimination and residential segregation emerged as important areas of debate among policymakers, politicians, community members, and activists. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 was the culmination of more than twenty years of advocacy and opposition, and marked a major step forward for the country in the promotion of equality. At the same time, as this chapter shows, the political, economic, and social structures that limited the opportunities for people of color to live where they choose created barriers that legal reforms could not, on their own, overcome.Zoning for SegregationWhile federal policies following the Civil War helped safeguard the civil rights of African Americans, those protections were short-lived or relatively ineffectual. Subsection 1982 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, for example, was the nation’s first fair housing law; but the requirement to demonstrate intentional discrimination limited citizens’ ability to make use of it (Fennell 2017: 391). Instead, with the end of Reconstruction, a set of state and local policies known as the Jim Crow laws instituted segregation in multiple domains. These laws suppressed African American voting and imposed the myth of “separate but equal” institutions and environments. The 1896 Supreme Court ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson - eBook - PDF

Furthering Fair Housing

Prospects for Racial Justice in America's Neighborhoods

- Justin P. Steil, Nicholas F. Kelly, Lawrence J. Vale, Maia S. Woluchem, Justin P. Steil, Nicholas F. Kelly, Lawrence J. Vale, Maia S. Woluchem(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Temple University Press(Publisher)

Having held hearings and debated the bill extensively in previous sessions, Congress now chiefly struggled over proce-dural issues. In February and March, the Democratic leadership maneuvered to obtain additional votes to cut off a filibuster by Southern conservatives. The cloture effort gained almost enough votes when Senate minority leader Dirksen threw his support in return for weakening the bill’s enforcement provision and reducing its coverage. In March, the release of the dramatic Kerner Commission report shook loose the remaining needed votes. 54 After passing the Senate, the bill went to the House, where it appeared it might expire in the Rules Committee. But the assassination of King on April 4, and the ensuing violence in the streets of Washington, galvanized The Origins of the Fair Housing Act of 1968 / 63 the House, which passed the Senate’s version of the bill by a wide margin. On April 11, Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968 into law, including Title VIII. The Provision That Inspired the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing Rule Consistent with its history, the Fair Housing Act aimed to stop discrimina-tion, first in the selling and renting of residences and second in the corollary activities of real estate brokering and lending. It covered anyone involved in private housing transactions, with the exceptions of owner-occupants who owned buildings with four or fewer dwellings or who sold their single-family houses without professional help. As in earlier proposed legislation, the Fair Housing Act prohibited discrimination in any form of real estate financ-ing. Beside prohibiting real estate steering and redlining by lenders, the law included a new provision to ban the practice of blockbusting. The 1968 law placed HUD in charge of enforcement, but the agency could only act in re-sponse to individuals’ complaints and use persuasion to change discrimina-tory behaviors or, as a last resort, refer the cases to the Justice Department. - eBook - PDF

A Decade of Federal Antipoverty Programs

Achievements, Failures, and Lessons

- Robert H. Haveman(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 banned discrimination (on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin) in sale, rental, and financing in 6 3 Henry J. Aaron, Shelter and Subsidies, The Brookings Institution, 1972; Robert Taggart III, Low-Income Housing: A Critique of Federal Aid (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1970); Arthur P. Solomon, Housing the Urban Poor (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1974); United States Commission on Civil Rights, Home Ownership for Lower Income Families: A Report on the Racial and Ethnic Impact of the Section 235 Program (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, June 1961); Michael A. Stegman, ed., Housing and Economics: The American Dilemma (Cam-bridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1970). 6 4 U . S . Commission on Civil Rights, Equal Opportunity in Suburbia, p. 36. Policy Developments in Employment and Housing 353 most of the private housing market as well as federally assisted units. These fair housing provisions established a variety of administrative procedures for filing complaints with the Secretary of HUD, for conciliation, and for litigation. In addition, the executive agencies of the federal government were required to administer their housing programs in an affirmatively nondis-criminatory manner. Affirmative action guidelines, however, were not estab-lished until 1972. Meanwhile the Supreme Court, acting upon a long-forgotten law, the Civil Rights Act of 1866, banned racial discrimination in the sale and rental of all property. The decision was made shortly after the passage of the fair housing provisions of 1968. 65 Jones v. Mayer Co. went beyond the limita-tion in the 1968 law on size of multifamily housing units and applied without regard to whether the owner-occupant conducted the sales or rental transac-tion. In another decision by a federal court in 1970, Shannon et al. - eBook - ePub

The Fight for Fair Housing

Causes, Consequences, and Future Implications of the 1968 Federal Fair Housing Act

- Gregory D. Squires(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

(Remarks on Signing the Civil Rights Act, Lyndon B. Johnson, April 11, 1968)With that, the Civil Rights Act of 1968 officially became the law of the land.The Fair Housing Amendments Act

While the passage of the Fair Housing Act was an undeniable civil rights victory, the true cost of the Dirksen Compromise would soon become clear. Without any significant enforcement power, HUD was incapable of doing anything other than attempting to reach a voluntary conciliation between parties. Private lawsuits and a small number of pattern-or-practice cases brought by the DOJ were not able to fill the void left by the lack of an administrative enforcement mechanism. Enforcement of state and local fair housing laws was spotty: whether or not the laws were enforced in a particular jurisdiction often depended upon whether any committed, experienced lawyers were willing to bring cases.As a result, in the decades to follow, the FHA would fail to live up to its promise to end housing discrimination and foster integrated living patterns. Residential segregation rates remained unacceptably high throughout the 1980s, a situation which scholars likened to apartheid. A 1979 national study by HUD found that housing discrimination was still pervasive. The study estimated that two million acts of housing discrimination took place each year (in contrast with just 5,000 complaints filed annually). It also found the probability of a black homeseeker experiencing discrimination was approximately 75 percent in the rental market and 62 percent in the sales market (Wienk et al. 1979: 64). As one commentator later noted, “Of all the civil rights battles fought during the last three decades, only housing discrimination appears to remain totally unabated, entrenched, and impervious to public policy and civil rights enforcement” (Kushner 1989: 1050).The coverage of the FHA remained an issue as well. The law included only race, color, religion, and national origin as protected characteristics. As the ensuing years would show, other categories of people were also in need of civil rights protections in housing. - eBook - ePub

Local Government Law

A Practical Guidebook for Public Officials on City Councils, Community Boards, and Planning Commissions

- Gerald A. Fisher(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Chapter 7Fair HousingProviding access to decent housing for all, free of discrimination, has long been an important objective in the United States, an objective that has escaped full realization in spite of considerable attention.Traditionally, for purposes of providing an adequate assurance of lawful and decent housing, communities often understood this to involve local government enforcement of zoning and construction code regulations. While such enforcement continues to be relevant, it has become well-recognized that lawful and decent housing requires more comprehensive action in order to resolve the problem of housing segregation that remains in our country. Perhaps the most pervasive additional effort at addressing this issue is embodied in a federal law known as the Federal Fair Housing Act (42 U.S.C. 3601 et seq.) which broadly declared in 1968 that it is “the policy of the United States to provide, within constitutional limitations, for fair housing throughout the United States.” In 1988, the Fair Housing Amendments Act expanded its protections.The Federal Fair Housing Act (or “FHA”) will be the focus of this chapter. The discussion will first consider an historical context, focused on the first half of the 1900s, when the problem of housing segregation took a turn for the worse during the two World Wars, as well as the period after World War II, when the problem was exacerbated as metropolitan areas were created throughout the country. We will then focus on three specific areas of activity in which local governments can become targets for legal action under FHA regulations, thus making the FHA relevant to local officials. The discussion will finally turn to a review of court decisions which discuss the manner in which claims are made against local governments, and reviewed by the courts, under the FHA. - eBook - PDF

Moving toward Integration

The Past and Future of Fair Housing

- Richard H. Sander, Yana A. Kucheva, Jonathan M. Zasloff(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Harvard University Press(Publisher)

Implementation of the Fair Housing Act, 1968–1975 145 4. The courts. The Supreme Court had unanimously upheld the consti-tutionality of all challenged provisions of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, so there was not much doubt that if FaHA was challenged on similar grounds, it would survive. But there were a host of other questions about how specific provisions might be interpreted—from questions of standing (such as, could a white person sue a landlord if aware of discriminatory policies keeping a building all-white?) to questions of proof (must actual discriminatory in-tent be proven?). One could, moreover, imagine that if Republicans recap-tured the White House, the judiciary would become more conservative in general and perhaps more hostile to civil rights enforcement. 5. Broader federal activity. The mandate to affirmatively further fair housing applied to the entire federal government. Potentially, this could mean federal reform in everything from veteran’s housing programs to the comptroller of the currency’s oversight of private lending practices. But if HUD was not proactive in holding other agencies accountable, from where would the impetus to fulfill this mandate come? From this list, it is evident why some observers might doubt whether FaHA would be any more effective than state fair housing efforts had been. But the list also shows that there were multiple, somewhat autonomous moving parts in the federal law; fair housing efforts might be effective in some dimensions and not in others. Nothing illustrates how easily FaHA might be underesti-mated than examining what proved to be perhaps the most important (and most overlooked) enforcement component: the Department of Justice. In April 1968, when President Johnson signed FaHA, Ramsey Clark was attorney general. Clark was an enthusiastic supporter of civil rights, and had been a forceful advocate for fair housing in testimony before a Senate committee in 1967. - eBook - PDF

Building Foundations

Housing and Federal Policy

- Denise DiPasquale, Langley C. Keyes, Denise DiPasquale, Langley C. Keyes(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

Chapter 5 Federal Fair Housing Policy: The Great Misapprehension George C. Galster Martin Luther King fell to an assassin's bullet on April 4, 1968. One week later an omnibus civil rights bill passed Congress, after languishing for years in committees. Title VIII of this bill prohibited discrimination against those who would rent or purchase homes on the basis of race, sex, creed, national-ity, or religion. Federal fair housing law figuratively was born out of King's casket. The passage of federal fair housing statutes brought us a step closer to the goal of equal housing opportunities for all citizens. With twenty years of hindsight it appears to be but a baby step, however, in light of two salient facts. First, illegal acts of housing discrimination continue to be perpetrated at an alarming rate. Recent audits that have utilized interracial pairs of testers have found, on average, that black homebuyers face at least a one-in-five chance of being discriminated against each time they confront a housing agent. 1 The comparable figures for black and Hispanic apartment seekers are one-in-two and one-in-three, respectively. Second, a high level of racial resi-dential segregation persists. On average, 79 percent of black households would need to move from their 1980 location in order to achieve complete integration of our larger metropolitan areas (where most blacks live). The comparable percentages are 48 and 43 for Hispanics and Asians, respec-tively. 2 Recent studies have found that the segregation of blacks within our large metropolitan areas has hardly changed since 1970. The isolation of His-panics from Anglos has increased in areas with significant gains in Hispanic population. 3 Why has federal fair housing policy apparently had such limited effi-cacy? I propose that federal fair housing policy has suffered from crucial mis-apprehensions over the ends of policy, the means of achieving these ends, and the process of implementing these means. - eBook - ePub

- Steven W. Bender, Raquel Aldana, Gilbert Paul Carrasco, Joaquin G. Avila(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

3 Discrimination in Housing Landlord DiscriminationAlthough the purchase of housing will also be discussed to some extent in this chapter, the focus will be primarily on the rental of housing. Latino/as are more likely than others to have the following characteristics associated with lower home-ownership rates:• householder is not a citizen; • householder is foreign-born; • foreign-born householder recently arrived in the United States; • young householder; • low income; • low educational attainment level; • residence located in central city; • residence in multifamily housing unit;• residence in high-cost housing market.1Many of the cases discussed in this chapter relate to African Americans, but a study conducted by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) reveals that discrimination against Hispanic renters has become more common than discrimination against African Americans.2The Civil Rights Act of 1964, although fairly comprehensive, did not prohibit private discrimination in housing. The need for such a provision became clear to Congress, however, in subsequent years, especially as young African Americans and Latino/as returned from fighting in Vietnam only to be denied housing because of their race. The assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, helped spur Congress into action, and the Civil Rights Act of 1968 was enacted a week later. As amended, Title VIII (8) of the 1968 law, also known as the Fair Housing Act (FHA), prohibits discrimination in housing based on race, color, national origin, and familial status, among other categories.At about the same time Congress enacted Title VIII, the Supreme Court revived a federal remedy for violations of the housing discrimination provision of the post–Civil War Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1982 (Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co - eBook - PDF

A Century of Civil Rights

With a Study of State Law Against Discrimination by Theodore Leskes

- Milton R. Konvitz(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Columbia University Press(Publisher)

Chapter 9 FAIR HOUSING PRACTICES Residential housing, despite its importance and its impact upon discrimination in other areas of community life, such as schools, recreational facilities, health and welfare service, and even em-ployment opportunities, appears to be the last of the major areas of discrimination that the states have been willing to attack. Thus, although several states had laws on their books before 1949 prohibiting discrimination in public housing projects, no really effective remedy was available to the person victimized by such discrimination until Connecticut extended the jurisdiction of its Civil Rights Commission in 1949 to include complaints involving public housing. It will be recalled that in that year Connecticut amended its public accommodations statute to broaden the duties of its Civil Rights Commission. The same amendment added the words all public housing projects to the list of place of public accommoda-tion in which discrimination was prohibited. 1 This created a new civil right under state law and provided an administrative rem-edy. The civil right was the right of all persons within the juris-diction of the state to full and equal consideration for public housing projects without discrimination based on race, creed, or color. The administrative remedy was the time-tested procedure established several years earlier as part of the FEP Law. In 1953 the legislature of Connecticut again amended its public accommodations statute. This time the specific listing of places 1 Public Act of July 13, 1949. Fair Housing Practices 237 included within the term place of public accommodation was dropped and general language substituted. The term was defined as any establishment, including, but not limited to, public housing projects and all other forms of publicly assisted housing, which caters or offers its services or facilities or goods to the general public (italics added). - eBook - ePub

- U.S. Government, U.S. Supreme Court, U.S. Congress(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Madison & Adams Press(Publisher)

(f) The provisions of law and Executive orders to Which subsection (e)(6) applies are–(3) cooperate With and render technical assistance to Federal, State, local, and other public or private agencies, organizations, and institutions Which are formulating or carrying on programs to prevent or eliminate discriminatory housing practices;(4) cooperate With and render such technical and other assistance to the Community Relations Service as may be appropriate to further its activities in preventing or eliminating discriminatory housing practices7(5) administer the programs and activities relating to housing and urban development in a manner affirmatively to further the policies of this title; and(6) annually report to the Congress, and make available to the public, data on the race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, handicap, and family characteristics of persons and households Who are applicants for, participants in, or beneficiaries or potential beneficiaries of, programs administered by the Department to the extent such characteristics are Within the coverage of the provisions of law and Executive orders referred to in subsection (f) Which apply to such programs (and in order to develop the data to be included and made available to the public under this subsection, the Secretary shall, Without regard to any other provision of law, collect such information relating to those characteristics as the Secretary determines to be necessary or appropriate).(1) title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964; (2) title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968; (3) section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973; (4) the Age Discrimination Act of 1975; (5) the Equal Credit Opportunity Act; (6) section 1978 of the Revised Statutes (42 U.S.C. 1982); (7) section 8(a) of the Small Business Act; - eBook - PDF

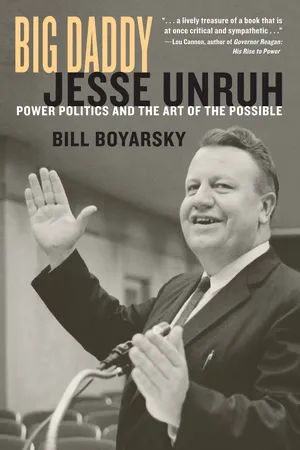

Big Daddy

Jesse Unruh and the Art of Power Politics

- Bill Boyarsky(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

It wasn’t just that he had the votes to push almost anything he wanted through the house. He was faster on his feet, smarter, wittier, more logical, and more eloquent than any of his col-leagues. When Unruh spoke, it was a performance not to be missed. His power, his personality, and his view that the legislature might already have done what it could for civil rights were all in play in the long debate over the most important bill of 1963, a proposal to give the state power to act against property owners who discriminated in the sale or rental of homes and apartment houses, a measure supporters called “fair housing.” The name rankled the opponents, who considered the plan most unfair. The legislation would give the state authority to step in and prohibit dis-crimination because of race, color, religion, or national origin in the sale or rental of housing. It would be a powerful weapon for minorities trying to break the color line. Judicial decisions had banned discrimination. Unruh’s own civil rights act had forbidden the housing industry from engaging in biased practices. But the aggrieved had to go to court to press their rights. The proposed law went much farther, allowing them to bring the investi-gatory power of the state down on the heads of property owners. Violators faced criminal penalties. A maximum penalty of six months in jail and a $500 fine awaited those found guilty of refusing to rent or sell to minori-ties. In other words, jail was a possibility for those who discriminated in housing sales or rentals, a practice that had been considered a right in white neighborhoods. Unruh’s attitude toward the open housing bill was complicated—too nu-anced for the simplicities of political debate. He retained the same sense of outrage he’d felt against bigotry since boyhood, saying in a speech: No man can stand before you and say that injustice and prejudice do not exist.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.