History

Margery Kempe

Margery Kempe was a 15th-century English mystic and author, known for writing the first autobiography in the English language. Her book, "The Book of Margery Kempe," details her religious experiences, including visions and conversations with God. Kempe's work provides valuable insights into medieval spirituality and the role of women in religious life during this period.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Margery Kempe"

- No longer available |Learn more

- Joseph Black, Leonard Conolly, Kate Flint, Isobel Grundy, Don LePan, Roy Liuzza, Jerome J. McGann, Anne Lake Prescott, Barry V. Qualls, Claire Waters(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Broadview Press(Publisher)

Margery Kempe c. 1373 – 1439 W idely varying descriptions of Margery Kempe have been proposed in the past century—mystic, eccentric, feminist, lunatic, saint, fanatic, heretic, visionary—but for literary purposes, one point about her is central: hers is often considered the first extant autobiography written in English. Dictated to two different scribes, The Book of Margery Kempe describes the spiritual awakening and religious fervor of a medieval woman who could neither read nor write, but who had a wide and heartfelt knowledge of theology from listening to sermons and lectures. Modeling herself after various female saints (Bridget of Sweden and Katherine of Alexandria, for example), Kempe was herself on a self-described quest for sainthood; in her autobiography she describes the many obstacles that stood in her spiritual path, as well as her shrewd approaches to dealing with the impediments. Her willingness to challenge powerful men—including the Archbishop of York—and her determination to follow her calling at any cost make her story as fascinating as it is remarkable. Margery Brunham Kempe’s early life was typical of a prosperous woman of the fifteenth century. Her father was an important man in the affluent port town of Bishop’s Lynn (now called King’s Lynn) in Norfolk, England. John Brunham was five times mayor of the town, two times Member of Parliament, and he held various other estimable positions. At the age of 20 Margery married John Kempe, also of Bishop’s Lynn; the couple had 14 children over the following 20 years. Kempe’s autobiogra-phy begins with her marriage, although she mentions having committed some sin, possibly of a sexual nature, before the age of 20 and having felt deeply remorseful about it ever since; she seemed to feel that no amount of penance or atonement would redeem her. - eBook - PDF

The Female Mystic

Great Women Thinkers of the Middle Ages

- Andrea Janelle Dickens(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- I.B. Tauris(Publisher)

A further challenge to under-standing Margery’s writing comes in the form of autobiography itself and the way that modern scholars in various disciplines have read this genre and its focus. Autobiography, some scholars posit, means that the spiritual is de-emphasized in order to focus on the individual. 8 Others have argued the opposite, stating that since Margery constantly refers to herself as ‘this creature’ she de-emphasizes the individual nature of her new genre of writing, the autobiography. Whether one decides to read it as an individual’s narrative or the narrative of a person who sees herself as a creature of God affects whether one finds a coherent spirituality in the work. The Book of Margery Kempe consists of two books of uneven length. The first book, which comprises the majority of the work, is structured around five contemplative visions that track her increasing spiritual progress. The first vision occurs during Advent; 9 it is one in which Margery sees herself within the Holy Family. This vision provides a bridge to connect her life as a mother and the life she desires as a holy woman, and it shows her able to attend first to Anne’s birth of the Virgin Mary and then Mary’s birth of Jesus, serving in the role of a nurse at the Incarnation. The image of Margery as nurse within a contemplative vision combines the active life (nurse) with contemplation (gazing upon the infant Jesus). Four other visions follow this, helping to structure the book’s tales about Margery’s wanderings. The second structuring meditation occurs during her pilgrimage to Jerusalem and describes her mystical marriage to Christ (once her marriage to John Kempe is renegotiated). 10 The third experience continues the themes of the second, and it is a meditation of the Passion The Female Mystic: Great Women Thinkers of the Middle Ages 166 - eBook - ePub

Mystical Theology and Contemporary Spiritual Practice

Renewing the Contemplative Tradition

- Christopher C. H. Cook, Julienne McLean, Peter Tyler, Christopher C. H. Cook, Julienne McLean, Peter Tyler(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

3 The mystical theology of Margery Kempe Writing the inner life Corinne SaundersAbstract

The Book of Margery Kempe , often described as the first autobiographical work in English, offers a remarkable and nuanced account of medieval visionary experience. Yet recent criticism has taken a largely historicist approach, moving away from exploration of Margery’s inner life. Drawing on the insights of the Wellcome Trust-funded interdisciplinary research project ‘Hearing the Voice’, this essay returns to Margery’s mystical theology and its role in her writing of the inner life. Margery’s inner voices and visionary experience more generally are placed in the context of her active domestic and religious life, and of other medieval religious writing, to illuminate the complex, intertextual yet individual quality of her narrative.Introduction

Six hundred years ago, Margery Kempe made the journey from King’s Lynn to Norwich, to visit the celebrated anchorite Dame Julian: the sole manuscript of The Book of Margery Kempe marks the visit in red in the margin. Margery seeks Julian’s advice on the ‘very many holy speeches and converse that our Lord spoke to her soul’ and her ‘many wonderful revelations’, to discover whether there is ‘any deception’ in them (77).1 Julian’s renown for good counsel is rooted in her own visionary experience, recorded in her Revelations of Divine Love .2 - eBook - PDF

- Jane Chance(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

In defense of Margery Kempe, recent criticism has centered on the issue of identity and female authorship (given the vexing problem of clerical and scribal written authority and the accuracy of the transmis- sion of oral and/or vernacular texts as constructed by an allegedly illit- erate woman), but usually always within a feminist context. 12 Most significant here is Lynn Staley’s powerful argument that Kempe artisti- cally manipulated her persona “Margery” in the way that Geoffrey Chaucer manipulated his alter ego “Geffrey” in his works. 13 In addi- tion, Margery’s outrageous behavior has intimated to some critics the possibility of parallels with or influence by (or upon) female literary char- acters, most particularly, Mary Magdalene in the mystery plays and saints’ lives and Chaucer’s Wife of Bath. 14 Other scholars have ignored her behavior but implicitly justified Kempe by drawing parallels between her LITERARY SUBVERSIONS OF MEDIEVAL WOMEN 100 text and those belonging to a written, masculinized literary tradition: specif- ically, Franciscan meditations 15 ; male mystics Walter Hilton and Richard Rolle 16 ; Bede and Chaucer 17 ; and William Thorpe and John Rogers. 18 However inherently misogynistic such diagnoses of psychological aberration may appear, they lead us back into the fruitful area of exam- ining Kempe’s eccentricity as a form of spirituality, which has only begun to be examined. 19 Scholars have not fully recognized the bizarre behavior of paradigmatic women from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries as a form of gendered spiritual “unhomeliness,” or holy alter- ity. Critical refusal to honor Kempe’s eccentricity as gendered contin- ues, even though Margery has been studied in relation to other religious women—for example, Marie of Oignies, Christina Mirabilis, and Elizabeth of Spalbeck 20 ; the king’s daughter of Hungary 21 ; Julian of Norwich and St. - eBook - PDF

- T. Pearman(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

The priest informs his readers of the rambling and unwieldy structure of the book, noting that “[t]hys boke is not wretyn in ordyr, every thyng aftyr other as it wer don, but lych as the mater cam to the creatur in mend whan it schuld be wretyn” (Proem: 49). Wendy Harding finds that, in collaborating with a scribe, Kempe creates with her text a dialogic writing that blurs the boundaries between illiteracy and literacy, the bodily and the spiritual. 17 Considered the first autobiographical text written in English, a hagiography of an exemplary woman’s journey to a spiritual life, and an elaborate fiction by a savvy author who exploits the “conventions of sacred biography and devotional prose [ . . . ] as a means of scrutinizing the very foundations of community,” Kempe’s Book certainly has resisted easy classification. 18 Instead of selecting one category or the other, I acknowledge the dangers of adopting an either/ or understanding of the text’s genre. Calling the Book an autobiography is inherently problematic, as autobiographical writing as we define it today did not exist in the Middle Ages. However, Kempe’s text, shaped as it is by her memories (as well as other hagiographies, mystical trea- tises, and devotional texts), does represent her responses to her everyday activities, a textual impulse that may be considered “autobiographical.” Relegating the text to the status of a hagiography or a fiction erases such impulses, vacating Margery Kempe the historical woman from the text. Each choice seeks to limit the text, which does not neatly fit one category, and to close Kempe within a stable subject position as autobiographical writer, hagiographic exemplar, or creator of the fic- tional character Margery. Thus, like Julian Yates, I consider the Book a hybrid text that includes elements of autobiography. - eBook - PDF

The Embodied Word

Female Spiritualities, Contested Orthodoxies, and English Religious Cultures, 1350-1700

- Nancy Bradley Warren(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- University of Notre Dame Press(Publisher)

69 In a scathing dismissal of The Book of Margery Kempe as a “proper” work of religious contemplation, Stephen Medcalf says, “Many have treated it as a treatise on contemplation. . . . To be that, it should have focused not on her idiosyncrasy but on God. But she does not know the difference.” 70 Though my reading of the Book differs radically from Medcalf ’s, the lack of differentiation between knowledge of God and knowledge of individual experience to which he points is in a way key to my argument. Part of the central point of Margery Kempe’s and Anna Trapnel’s reformist visions of society is that in writing about their idio- syncratic experiences they are writing about God as well as about human others. 71 Staley notes that The Book of Margery Kempe provides a model of com- munity different from the one found in “official pronouncements about the nature of English society.” Margery Kempe, she says, defines “com- 178 T h e E m b o d i e d Wo r d munity in terms of what it can include and thus in terms of those indi- viduals who can now be accommodated in this new society whose foun- dation is love.” The representation of her life in the Book “translates into her mother tongue . . . a vita Christi in the form of a social gospel that breaks down, rather than erects, boundaries.” 72 Margery Kempe’s em- bodied experience of the incarnate Christ recorded in her reiterable, in- carnational (auto)biography contains the script to perform a capacious Christian community not unlike that represented in Grace Mildmay’s meditations or in Julian’s Showings. In other words, Margery posits a re- formed social body grounded in the accessibility to all of Christ’s body, one avenue of access to which is through her own body and her text. - eBook - ePub

Margery Kempe

A Book of Essays

- Sandra J. McEntire(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

The Book where she is adding things she forgot in the main narrative, she gives us the interpretative key to her text: “Also, whil þe forseyd creatur was ocupijd a-bowte þe writyng of þis tretys, sche had many holy teerys & wepingys … and also he þat was hir writer cowde not sumtyme kepyn hym-self fro wepyng” (219) [Also, while the foresaid creature was occupied about the writing of this treatise, she had many holy tears and weepings… and also he that was her writer could not sometimes keep himself from weeping]. Though many women wept tears of devotion, only Margery Kempe has left such a poignant and instructive link between feeling and writing, between the writer’s and the reader’s emotions.University of CincinnatiNOTES

1. For other work on Kempe and the general tradition of mysticism see Clarissa Atkinson, Mystic and Pilgrim; Janel M. Mueller, “Autobiography of a New ‘Creator’”; Karma Lochrie, “The Book of Margery Kempe: The Marginal Woman’s Quest for Literary Authority”; Sue Ellen Holbrook, “Order and Coherence in The Book of Margery Kempe.”2. Sandra McEntire, “Walter Hilton and Margery Kempe: Tears and Compunction,” and “The Doctrine of Compunction from Bede to Margery Kempe”; Susan Eberly, “Margery Kempe, St. Mary Magdalene, and Patterns of Contemplation.”3. Denise L. Despres, “The Meditative Art of Scriptural Interpolation in The Book of Margery Kempe ” and Ghostly Sights: Visual Meditation in Late Medieval Literature.4. Elona K. Lucas, “The Enigmatic, Threatening Margery Kempe”; Maureen Fries, “Margery Kempe”; Susan Dickman, “Margery Kempe and the Continental Tradition of the Pious Woman.” Dickman’s essay makes the strongest statement: “In her singularity, isolation, and individuality, Margery Kempe represents a medieval, English middle-class version of one of the most important feminist movements in history” (166). Hope Phyllis Weissman, in “Margery Kempe in Jerusalem: Hysteria compassio in the Late Middle Ages,” explains how, though Kempe did not “escape thesystem,” she succeeded in “affronting it,” by her “self-created oxymoron of a married virgin” (217).5. For bibliographic information and overview of continental women mystics, see Valerie Lagorio, “The Medieval Continental Women Mystics: An Introduction.”6. Susan Dickman in her 1984 essay believes that the lack of evidence about tertiaries in England indicates that the institution simply did not exist there, at least for women.7. - eBook - PDF

The Romance of Origins

Language and Sexual Difference in Middle English Literature

- Gayle Margherita(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

1 * This perspective was revived during the last decade, which saw a re-newed interest in women mystics in general, and Margery in particular. In her book Mystic and Pilgrim: The Book and the World of Margery Kempe, Clarissa Atkinson places Margery within the tradition of affective piety as revealed in the words and deeds of women mystics such as Catherine of Siena and Dorothea of Montau. 19 Atkinson acknowleges that modern definitions of hysteria may be helpful in the interpretation of Margery Kempe, but cautions that modern judgments about 'normal' and healthy sexuality are not applicable to medieval Christians, whose values, socializa-tion, and world view were so unlike our own. 20 Caroline Bynum, who includes Margery in her study of food practices and body image in the lives of women saints and mystics, also takes pains to de-pathologize women's spirituality. She also sees the resolution of this dilemma in accu-rate contextualization: Those who have felt it necessary to defend the past (always a risky undertak-ing) have . . . had either to take the offensive and blame institutions or indi-viduals who oppressed women or to ignore the full range and extremism of the self-torturing behavior and concentrate on other aspects of women's spirituality. But when we place even the most extravagant fasting and self-mutilation in its medieval context it is not clear that such behavior was rooted either in self-hatred or in dualism. 21 According to Bynum, diligent scholarship can strip away the veils of mod-ern prejudice that insists that self-mutilation and starvation are pathologi-cal behaviors; by amassing enough empirical evidence, one can accurately re-construct the medieval context that will recuperate these strange be-haviors for a canonical history. - eBook - PDF

The Gift of Tongues

Women's Xenoglossia in the Later Middle Ages

- Christine F. Cooper-Rompato(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Penn State University Press(Publisher)

11 Part 1: Miraculous Translation in The Book of Margery Kempe It is well recognized that the Book is patterned on sacred biographies and visionary texts like those of St. Bridget of Sweden and Marie d’Oignies, while at the same time diverging from its models quite significantly. 12 My aim in 10. Perhaps the most extreme argument for Kempe’s control is voiced by Lynn Staley, who suggests that the scribe might have been created by Kempe herself: ‘‘Since Kempe stresses the amount of time Margery spent with her scribe (216), it is likely she exerted a good deal of control over the text itself: either she wrote it herself and created a fictional scribe, or she had it read back to her and was aware of exactly what was in the text.’’ Staley, Margery Kempe’s Dissenting Fictions, 33. 11. In this chapter, I am employing Staley’s distinction, as set out in Margery Kempe’s Dis- senting Fictions, between Kempe the author and Margery the character; Staley sees the latter as a literary construct in much the same way as we distinguish between Chaucer the writer and Chaucer the pilgrim, and Langland the author and Will the pilgrim. I do not go as far, however, as to assert that the scribe is the creation of Kempe. For further discussion of the Book’s author- ship, see Nicholas Watson, ‘‘The Making of The Book of Margery Kempe,’’ in Voices in Dialogue: Reading Women in the Middle Ages, ed. Linda Olson and Kathryn Kerby-Fulton (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2005), 395–434, and Felicity Riddy, ‘‘Text and Self in The Book of Margery Kempe,’’ in Olson and Kerby-Fulton, Voices in Dialogue, 435–53. 12. As the lives and works of holy women, including SS. Bridget of Sweden and Elizabeth of Hungary, are translated to Margery by the priest (and of course she hears vitae in sermons and in other places), she in turn translates the lives and their visions of these women into her own experience. - eBook - PDF

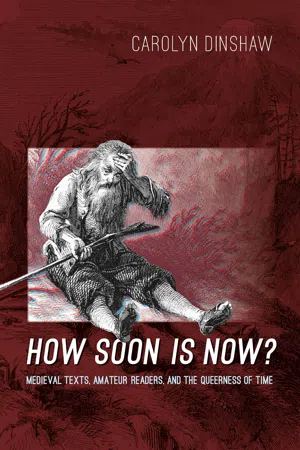

How Soon Is Now?

Medieval Texts, Amateur Readers, and the Queerness of Time

- Carolyn Dinshaw(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Duke University Press Books(Publisher)

It is as if she is in another temporal dimension even from the people who take her under their wings; others insist that Margery eat, others speak for her (“the good lady was hir auoket [ advocate ] and answeryd for hir,” as if Margery is else-where), others take her as an “exampyl” (148).6 They put her into, or con- chapter three 108 nect her to, the stream of mundane, everyday life, out of which she has precipitated. These complex temporal reckonings, and especially an expanded under- standing of contemporaneity, the now , begin this investigation of the Book of Margery Kempe and nonmodern temporalities, not only the tem-poral encounters represented in the book but also the temporalities of readers’ encounters with the book in turn. My hypothesis is that read-ing the book’s multiple temporalities opens up temporal avenues for post-medieval readers in turn, but already we have encountered something like temporal bullying in the text itself.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.