History

Mesa Verde

Mesa Verde is a UNESCO World Heritage site located in Colorado, USA, known for its well-preserved cliff dwellings built by the Ancestral Puebloans. These ancient structures, dating back to the 12th century, provide valuable insights into the lives and culture of the indigenous people who inhabited the region. Mesa Verde is a significant archaeological and historical site, attracting visitors from around the world.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

9 Key excerpts on "Mesa Verde"

- eBook - ePub

- Don Watson(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Perlego(Publisher)

In 1906, one-half of the great mesa was set aside as Mesa Verde National Park in order that the ruins might be preserved for all time and made accessible to visitors. Cliff Palace and some of the other cliff dwellings have been excavated and out on the mesa tops ruins of earlier types have been excavated to complete the archeological story. In the nearby museum are to be seen the things which have been found in the ruins. Displayed in their chronological order they tell the story of the ancient inhabitants of the Mesa Verde.It is a fascinating story of a vanished people. For endless centuries they dominated the Mesa Verde, passing through higher and higher stages of culture. When an unendurable calamity forced them to leave they left behind abundant evidence of their skill and industry. With the care they now receive Cliff Palace, Spruce Tree House, Sun Temple and the innumerable other ruins will stand forever as monuments to the skill of their ancient builders.Mesa Verde National Park was created to preserve the works of those prehistoric people. Slow, silent centuries have spread a cloak of mystery over it and visitors should come with open minds, prepared to hear an absorbing story of a strange people. Complete enjoyment and understanding come only to the visitor who is able to leave his modern self behind, momentarily, and live and think in terms of the past.2 DISCOVERY

After the cliff dwellings were deserted by the Pueblo Indians late in the thirteenth century they stood, unmolested by man, for many hundreds of years. The owls and pack rats took them over and enjoyed their security, but from all evidence it was many centuries before men again entered the caves.The Indians themselves may have intended to return when conditions became normal again but they never came back. There is no evidence that farming Indians ever lived in the Mesa Verde after its desertion by the ancient people. Other Indians came but they were hunters and they seem to have shunned the silent cave cities.A couple of centuries after Mesa Verde was deserted an important event took place, an event that was to have a strange effect on it at a later date. America was rediscovered!Fifteen thousand years after the Indians discovered the continent from the west, white men entered it from the east. A new people blundered into the western hemisphere that had so long belonged to the Indians. - eBook - ePub

For the Enjoyment of the People

The Creation of National Identity in American Public Lands

- Mary E. Stuckey(Author)

- 2024(Publication Date)

- University Press of Kansas(Publisher)

104 The site is enormous, complex, and intricate. Visitors with little knowledge going into the park face challenges in understanding it.Historically, at Mesa Verde the NPS has been better at including historical Indigenous cultures than contemporary ones.105 They are making serious efforts to include contemporary Indigenous voices in park interpretation, but they have much to overcome. The foundation document, for example, is unsurprisingly focused on archeology: “Mesa Verde National Park protects, preserves, researches, and interprets the archeological landscape including more than 600 cliff dwellings, wilderness values, and remarkable scenic resources in southwest Colorado.”106 But there are connections to present Indigenous people—the park’s interpretive themes include the interaction between Puebloan people and the natural and social environments, history and development of the park itself, its links between past and present, its natural landscapes and processes, and its archeology.107 The current park website notes, “Today, the park protects the rich cultural heritage of 26 [unnamed] tribes and offers visitors a spectacular window into the past.”108 This shift from consideration of the past alone to the past as connected to living Indigenous peoples is important. It treats Indigenous heritage as belonging to Indigenous people as well as to the nation and opens the possibility of more equitable treatment within the parks. This possibility has been a long time coming, and yet it creates questions of what must be shared, and what Native peoples may retain solely to themselves even as they are included in the nation.Interpreting Mesa VerdeFrom very early on, the federal government claimed ownership of Mesa Verde and its cultural heritage resources. In so doing, they also claimed ownership over at least some elements of Indigenous culture, which became absorbed into the nation’s cultural heritage. In a 1919 - eBook - ePub

- (Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Lonely Planet(Publisher)

More than 700 years after its inhabitants disappeared, Mesa Verde retains an air of mystery. No one knows for sure why the Ancestral Puebloans left their elaborate cliff dwellings in the 1300s. It's a wonderland for adventurers of all sizes, who can clamber up ladders to carved-out dwellings, see rock art and delve into the mysteries of ancient America.Mesa Verde National Park occupies 81 sq miles of the northernmost portion of the mesa. Ancestral Puebloan sites are found throughout the park's canyons and mesas, perched on a high plateau south of Cortez and Mancos.The National Parks Service (NPS) strictly enforces the Antiquities Act, which prohibits the removal or destruction of any antiquities and prohibits public access to many of the 4000 known Ancestral Puebloan sites.History

A US army lieutenant recorded the spectacular cliff dwellings in the canyons of Mesa Verde in 1849–50. The large number of sites on Ute tribal land, and their relative inaccessibility, protected the majority of these antiquities from pothunters.The first scientific investigation of the sites in 1874 failed to identify Cliff Palace, the largest cliff dwelling in North America. Discovery of the ‘magnificent city’ occurred only when local cowboys Richard Wetherill and Charlie Mason were searching for stray cattle in 1888. The cowboys exploited their ‘discovery’ for the next 18 years by guiding both amateur and trained archaeologists to the site, particularly to collect the distinctive black-on-white pottery.When artifacts started being shipped overseas, Virginia McClurg of Colorado Springs was motivated to embark on a long campaign to preserve the site and its contents. McClurg’s efforts led Congress to protect artifacts on federal land, with the passage of the Antiquities Act establishing Mesa Verde National Park in 1906. - eBook - ePub

Ancient Lives

An Introduction to Archaeology and Prehistory

- Brian M. Fagan(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Both in Mesa Verde itself and in the surrounding countryside, large villages which were almost towns were home to between 1,000 and 2,500 people, living in room clusters associated with kivas and other ceremonial buildings. Everywhere in Mesa Verde, the emphasis was on individual communities. Judging from the numerous kivas, there was considerable cooperative and ritual activity, and there were numerous occasions when inhabitants of different communities organized large labor parties to carry out sophisticated water control works and other communal projects. This Ancestral Pueblo tradition was quite similar to that of Chaco Canyon, with its intricate mechanisms for integrating dispersed communities, or the chiefdoms of the South and Southeast, with their large centers and satellite villages.The twelfth and thirteenth centuries saw the culmination of four centuries of rapid social and political development in the Mesa Verde region. About 1300, however, Pueblan peoples abandoned the entire San Juan drainage, including Mesa Verde. They moved in scattered groups southward and southeastward into the lands of the historic Hopi, Zuñi, and Rio Grande pueblos, where their ultimate descendants live to this day. Following the abandonment of large areas of the Southwest in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth century, large settlements formed in previously sparsely inhabited areas. Some of these pueblos are recognized as those of direct ancestors of modern communities.Figure 14.11 The Cliff Palace at Mesa Verde.(Brad Boserup/Thinkstock)Southwestern Pueblo society never achieved the cultural complexity found in eastern North America or among the Hawaiians or Tahitians, but it achieved the limits of regional integration possible for an area where rainfall was irregular and the climate was harsh. Perhaps, the best way to describe much southwestern organization is as a theocracy, a government that regulated religious and secular affairs through individuals, like chiefs, and kin groups or associations (societies) that cut across kin lines. The basic social and economic unit was the extended family but, for hundreds of years, southwestern peoples fostered a sense of community and undertook communal labors like irrigation works using wider social institutions that worked for the common good. - eBook - PDF

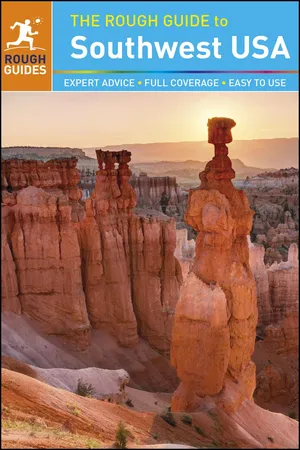

- (Author)

- 0(Publication Date)

- Rough Guides(Publisher)

Consisting of several well-preserved three-storey structures, snugly moulded into the recesses of a rocky alcove and fronted by open plazas, the neat little village was occupied from 1200 AD until 1276 AD. One kiva has been re-roofed, and visitors can enter the dusty, unadorned interior by way of a ladder. Allow around 40min for the complete half-mile loop. 78 1 THE FOUR CORNERS SOUTHWEST COLORADO Ruins Road April to late Oct, daily 8am–sunset Ruins Road , beyond the Chapin Museum area, has two one-way, six-mile loops. The park’s two best-known attractions, Cliff Palace and Balcony House, are on the eastern loop, and can be explored on guided tours only. To see them properly, be sure to buy tour tickets before you come this far; once here though, it’s well worth exploring the Mesa Verde: A HUMAN HISTORY Although Archaic sites in Montezuma Valley, below Mesa Verde, date back to 5500 BC, the earliest trace of humans found on the mesa itself is an Ancestral Puebloan pithouse from 550 AD. People first moved to the mesa, therefore, around the time they acquired the skill of pottery. Not so much farmers as gardeners, they continued to gather wild plants and hunt deer and rabbits as well as grow small fields of corn and own dogs and turkeys. For five hundred years, they lived in pithouses dug into the floors of sheltered caves; then, around 1100, they congregated in walled villages on the mesa-tops. A century later, they returned to the canyon-side alcoves to build the “palaces” for which Mesa Verde is now famous. Archeologists believe each settlement held significantly fewer people than it did rooms; the largest, Cliff Palace , housed a population of around 120. Two or three people may have slept in a typical living room, measuring six feet by eight feet, while each family had its own kiva (see p.463), which when not in ceremonial use was used for weaving and domestic activities. - eBook - ePub

Cliff Dwellings of the Mesa Verde

A Study in Pictures

- Don Watson(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Perlego(Publisher)

CLIFF DWELLINGS OF THE Mesa Verde

A Story in Pictures Mesa Verde Museum Association LogoDon WatsonMesa Verde Museum Association Mesa Verde National Park ColoradoDISCOVERY OF THE FIRST CLIFF DWELLINGS

Although the Spaniards were in the Mesa Verde region as early as 1765, there is no record of their having seen the cliff dwellings. It is probable, however, that they gave the great mesa its name, which in Spanish means, “green table.” First mention of the name was made by Professor J. S. Newberry, a geologist, who climbed to the summit of the mesa in 1859. From the manner in which Newberry used the name, “Mesa Verde,” in his report there can be no doubt that it had been applied prior to that time.In 1874, Mr. W. H. Jackson, later famous as the “Pioneer Photographer,” came into the region. Immediately upon reaching the mining camps of the La Plata Mountains, Jackson, who was making a photographic survey for the government, began to hear of ancient ruins in the Mesa Verde. Intrigued by these stories he hired a garrulous miner, John Moss, to guide him to the ruins which were said to be in the cliffs of the canyon of the Mancos River.Entering the canyon on September 9, 1874, the party traveled slowly, carefully scanning the cliffs far above. According to John Moss the ruins would be found in caves in the sheer sandstone faces. Although many weary miles were covered no cliff dwellings were seen and by the time evening camp was made the men were beginning to lose faith in their guide. Impatiently one of the men asked Moss where the ruins were. Without looking up from the campfire Moss waved his arm at the cliff above.Suddenly the discovery came. Just as the last rays of the sun lighted the uppermost cliff one of the men spied a small dwelling. Seven hundred feet above them it clung to the face of the cliff. The men began to scramble up the canyon wall and just as darkness fell Jackson and another man entered the little ruin. The next morning Jackson returned for his pictures. Thus fame came to the little cliff dwelling shown in the picture below. Not only was it the first Mesa Verde cliff dwelling known to have been entered by white men but it was definitely the first ever to be photographed and the first to be named. Jackson called it Two-Story Cliff House. Although Jackson discovered more small cliff dwellings in the Mancos Canyon, Two-Story Cliff House was the finest and the only one he named. - eBook - PDF

- Jonathan Goldberg, Michèle Aina Barale, Michael Moon, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Michèle Aina Barale, Michael Moon, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick(Authors)

- 2001(Publication Date)

- Duke University Press Books(Publisher)

Camera Chronicle (1941). 39 Not only do both authors treat the site as a kind of national monument or originary moment in U.S. history, they also stress the peacefulness of the former inhabitants and the high level of their artistic accomplishments ( LG, 67). ‘‘Perhaps more than any other place in the United States,’’ Gilpin writes, ‘‘one gains a feeling of antiquity at Mesa Verde. The warm, brilliant sun of the Southwest imbues these ancient buildings and creates a lasting sense of peace’’ ( Pueblos, 38); her sun-infused shots create this impression as well. So, too, Tom’s first description of the sculptural city seen through the snow stresses its ‘‘immortal repose,’’ ‘‘the calmness of eternity’’ ( Professor’s House, 180), a past preserved in amber. Gilpin’s description of the ruin at Betatakin, whose buildings, made of the same stone as the cave in which they are set, produce ‘‘an extraor-dinary semblance of unity, as though it were all the work of a giant sculptor’’ ( Pueblos, 62), guides her composition and has its echo in Tom’s estimation of the Cliff City: ‘‘It was more like sculpture than anything else’’ (180), a characteristically laconic statement that takes in canyon, cave, and buildings, held together in a symmetry that ‘‘made them mean something.’’ Gilpin’s statements and, indeed, her sharp-edged, close-up pho-tographs of the ruins at Mesa Verde correspond to Cather’s writing, sharing the modernist aesthetic that regards them as timeless sculp-ture. 40 Moreover, the ‘‘chronicle’’ of Gilpin’s book parallels Cather’s plotting. - Charles L. Douglas(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Perlego(Publisher)

Under the auspices of the Wetherill Mesa Archeological Project, the flora of the park recently was studied by Erdman (1962), and by Welsh and Erdman (1964). These studies have revealed stands of several distinct types of vegetation in the park and where each type occurs. This information greatly facilitated my study of the mammals inhabiting each type of association. The flora and fauna within the park are protected, in keeping with the policies of the National Park Service, and mammals, therefore, could be studied in a relatively undisturbed setting.Thus, the abundance of these two species of Peromyscus, the botanical studies that preceded and accompanied my study, the relatively undisturbed nature of the park, and the availability of a large area in which extended studies could be carried on, all contributed to the desirability of Mesa Verde as a study area.My primary purpose in undertaking a study of the two species of Peromyscus was to analyze a number of ecological factors influencing each species—their habitat preferences, how the mice lived within their habitats, what they ate, where they nested, what preyed on them, and how one species influenced the distribution of the other. In general, my interest was in how the lives of the two species impinge upon each other in Mesa Verde.PhysiographyThe Mesa Verde consists of about 200 square miles of plateau country in southwestern Colorado, just northeast of Four Corners, where Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona and Utah meet. In 1906, more than 51,000 acres of the Mesa Verde were set aside, as Mesa Verde National Park, in order to protect the cliff dwellings for which the area is famous.The Mesa Verde land mass is composed of cross-bedded sandstone strata laid down by Upper Cretaceous seas. These strata are known locally as the Mesaverde group, and are composed, from top to bottom, of Cliff House sandstone, the Menefee formation, the Point Lookout sandstone, the well known Mancos shale, and the Dakota sandstone, the lowest member of the Cretaceous strata. The Menefee formation is 340 to 800 feet thick, and contains carbonaceous shale and beds of coal.- eBook - ePub

Antiquities of the Mesa Verde National Park

Cliff Palace

- Jesse Walter Fewkes(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Perlego(Publisher)

Additional specimens can be obtained, however, from other ruins near it which will throw light on the culture of Cliff Palace. It is appropriate, therefore, to point out, at the very threshold of our consideration, that a continuation of archeological work in the Mesa Verde National Park is desirable, as it will add to our knowledge of the character of prehistoric life in these canyons. The next work to be undertaken should be the excavation and repair of a Mesa Verde pueblo. The extensive mounds of stone and earth on the promontory west of Cliff Palace have not yet been excavated, and offer attractive possibilities for study and a promise of many specimens. Buried in these mounds there are undoubtedly many rooms, secular and ceremonial, which a season's work could uncover, thus enlarging indirectly our knowledge of the cliff-dwellers and their descendants. [2] The writer considers it an honor to have been placed in charge of the excavation and repair of Cliff Palace, and takes this occasion to express high appreciation of his indebtedness to both the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and the Secretary of the Interior for their confidence in his judgment in this difficult undertaking. Maj. Hans M. Randolph, superintendent of the Mesa Verde National Park, gave assistance in purchasing the equipment, making out accounts, and in other ways. During the sojourn at Cliff Palace the writer was accompanied by Mr. R. G. Fuller, of the Peabody Museum of Harvard University, a volunteer assistant, who contributed some of the photographs used in the preparation of the plates that accompany this report. The writer is indebted also to Mr. F. K

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.