History

Operation Iraqi Freedom

Operation Iraqi Freedom was a military campaign led by the United States and a coalition of allies to overthrow the regime of Saddam Hussein in Iraq. Launched in 2003, the operation aimed to eliminate weapons of mass destruction and promote democracy in the region. The conflict resulted in the eventual capture and execution of Saddam Hussein, but also led to a prolonged period of instability in Iraq.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Operation Iraqi Freedom"

- eBook - ePub

- Major Michael Andrew Kappelmann(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Tannenberg Publishing(Publisher)

CHAPTER 4 — Operation Iraqi Freedom

In 2003, the U.S. led a coalition effort to invade Iraq and forcibly remove the Ba’athist totalitarian regime of Saddam Hussein. American political leadership envisioned this campaign as enabling its strategic goals in GWOT by establishing a functional representative government with the rule of law in the heart of the Middle East. The operational design however, was arguably incompatible with this strategy in the sense that the campaign, though remarkably successful in a military sense, undermined the conditions necessary to achieve the desired political end state. Further, optimistic assumptions at the strategic level about how the Iraqi people would react to foreign occupation and governance were not realistic.This chapter summarizes OIF from March 2003 to August 2004. The conventional phase of the campaign was complete in a matter of weeks, shattering the Iraqi armed forces and capturing physical objectives in a lightning manner. In the aftermath, the U.S. demonstrated that it had given little planning to post-war reconstruction and administration, and had allocated inadequate resources for doing so. An insurgency, mostly in the Sunni Arab regions, began and steadily grew over the following year. In April 2004, an uprising exploded among the Shi’a Arabs, leading to some of the deadliest days of the conflict for U.S. and coalition forcesStrategic Context

American political leadership envisioned OIF not as an end in its own right but as an enabling operation to the strategic ends of a world-spanning war. Following the al-Qaeda terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, the U.S. adopted a national security strategy of pre-emptive engagement in order to target and eliminate threats from abroad before they can cause harm to the U.S. or its allies. Worldwide efforts against al-Qaeda, other terrorist organizations, and those states believed to sponsor them would fall under the moniker “Global War on Terrorism.”{161} - eBook - ePub

Strategic Preemption

US Foreign Policy and the Second Iraq War

- Robert J. Pauly(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Chapter 5 Operation Iraqi Freedom IntroductionThe diplomatic battles which foreshadowed the US-led invasion, in many ways overshadowed the actual military phase of the campaign to oust the regime of Saddam Hussein. The US and coalition military build-up in the region was slow and deliberate. The slow pace of the diplomatic intercourse allowed the US and its allies to preposition troops, aircraft, ships and other military equipment. The only major hurdle faced in the deployment was the refusal of Turkey to allow the US to launch a northern front from its territory. This necessitated some last minute redeployments, but the main strategy and force arrangements were relatively unaffected by Turkey’s decision.Just as Bush allowed Powell considerable freedom of action in shaping US diplomacy during the prelude to the war, the President also allowed Rumsfeld and the Defense Department’s senior officers wide latitude to formulate and implement their preferred strategy. Freed from the perceived constraints of a multilateral military coalition, and its implicit political complications, US military planners sought to deploy the full range of American assets and capabilities in a campaign that would both showcase US firepower and minimize casualties. The administration sought a swift military victory as a means to entice other states to participate in the stabilization and nation building missions that would follow the assumed fall of the regime. In this fashion, Bush and his senior aides hoped that the conflict would follow the Afghan model in which US forces undertook the majority of combat missions, but coalition members provided the bulk of the peacekeeping and stabilization forces.Central to the military plans was the concept of rapid dominance (which came to be known as “shock and awe”). Rapid dominance involved the use of extensive firepower and advanced weaponry. Large amounts of precision-guided and advanced munitions would hit targets within minutes of each other or even simultaneously. It was meant to exert a tremendous psychological impact on the enemy and to demoralize and bewilder enemy troops into inaction or retreat or outright surrender. Rapid dominance was the logical extension of the Weinberger-Powell Doctrine and the legacy of Vietnam. The concept was designed to maximize the military and intelligence advantages of the United States and to ensure a quick and relatively painless victory. US forces could, therefore, prevent the grinding and bloody ground combat that the nation faced in Vietnam. The confidence of the Defense Department was such, that it decided to embed reporters with military units in order to provide firsthand accounts of operations so they could “live, work and travel as part of the units in which they are embedded in order to facilitate maximum, in-depth coverage of US forces in combat and related operations.”1 - Alastair Finlan(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Academic(Publisher)

CHAPTER SIX Operation Iraqi FreedomS hock and awe is a concept that promotes the idea of rapid dominance over an enemy’s “system of systems” through use of precision bombing.Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) is one of the most unusual and controversial campaigns of the modern era. Ostensibly, it appears to be a remarkable military victory, but a closer analysis of the fighting and the aftermath paint quite a different picture. A small coalition made up primarily of American and British forces in the face of widespread international opposition invaded Iraq. This extraordinarily small force package managed in a matter of weeks to topple the regime of Saddam Hussein. Notwithstanding various claims that OIF represented a new way of warfare or vindicated Rumsfeld’s transformation thesis, it was, in reality, a very traditional campaign that reflected archetypal trends in the contemporary American way of waging war. It was heavily fixated at the operational ground level on attacking targets that were key features of the previous Gulf War I model, the Iraqi military forces, and, especially, the Republican Guard. Senior commanders in OIF placed a great emphasis on the joint nature of the campaign, but in theater, the three armed services of the United States reverted to type and largely fought their own individual battles with a heavy reliance on cultural preferences. The overall visions and predictions of US political and key military elites about the type of enemy and how the campaign should be fought proved to be found greatly wanting in the deserts of Iraq. As such, the direction of the operation and eventual success, in the same manner as Operation Enduring Freedom, rested heavily on ad hoc decisions made by senior commanders in the field against an enemy whose incompetence provided them with enormous latitude for error.The challenges of IraqThe strategic and operational challenges posed by OIF were immense and manifold. In terms of geography, Iraq is the size of Germany and Austria combined and from Kuwait, the main start line for the invasion forces, to the capital was a distance of several hundred miles. John Keegan eloquently illustrates the geography issue facing the invading forces and argues that “not only is Iraq a difficult country to invade from the south, because of the narrowness of the point of entry, it is also a difficult country to conquer, because of the distance from the point of entry to Baghdad, over 300 miles to the north.”1 Iraq also shared various borders with quite a mélange of neighbors; some of whom would be friendly to US forces, some neutral and others not. These included Kuwait, Saudi Arabia in the southwest, Jordan in the west, Syria in the northwest, Turkey in the north, and Iran in the east. An important issue that appeared to be overlooked by Central Command (CENTCOM) planners and the Office of the Secretary of Defense was that securing these borders would be vital to the security of the post-Saddam environment, but only large amounts of ground forces could achieve this vital state of affairs. With a population of 24 million2 divided roughly into three ethnic groups, the Shiites who represented the majority in the south, the Sunni, the minority and traditional rulers of Iraq in the west and located in the center, and the Kurds in their own semi-autonomous region in the north, the coalition also faced a very challenging population control dimension. Despite the neoconservative dogma3- eBook - PDF

Air Power in the Age of Primacy

Air Warfare since the Cold War

- Phil Haun, Colin Jackson, Tim Schultz(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

6 The Result Is Never Final: Operation Iraqi Freedom The Greater Thirty Years War, 1990– Heather Venable* The real winner is the side that has established the framework for the next war (a decidedly realist strategic position) or the conditions for a lasting peace (an idealist outlook). 1 Although it is common to refer to operations in Afghanistan as the “longest war,” the United States and its coalition partners have been applying air power in Iraq for more than three decades, ranging widely across the spectrum of nonkinetic roles, including mobility and recon- naissance, to kinetic missions from strategic attack to close air support. In this vein, Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, is better told not as the story of a relatively quick and overwhelm- ingly successful joint air-ground campaign but as one chapter of a thirty years’ war. Placed in this context, OIF reveals how technological super- iority may enable short-term goals yet distract attention from the long- term complexities of war. From this perspective, Operation Desert Storm, the US-led coalition’s liberation of Kuwait in 1991, and the initial weeks of OIF are outbreaks of conventional conflict amidst a longer trend of low-level air power employ- ment. This framework highlights decades of low-grade violence punctu- ated by bouts of more traditional conflict, without long-term decisive effect. Neither Desert Storm nor OIF ended in a clear-cut manner because nation states, nonstate actors, and individuals never stopped using violence to achieve their political objectives. 2 * The views expressed by the author do not reflect those of the US government, the Department of Defense, or any of its organizations. 1 Everett Dolman, quoted in Rich Ganske, “Counter Terrorism, Continuing Advantage, and a Broader Theory of Victory,” Strategy Bridge, March 23, 2014. - eBook - PDF

9/11 and the Wars in Afghanistan and Iraq

A Chronology and Reference Guide

- Tom Lansford(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- ABC-CLIO(Publisher)

In an address to the nation on the evening of March 20, Bush announced the invasion of Iraq. The president stated, “Our nation enters this conflict reluctantly, yet our purpose is sure. The people of the United States and our friends and allies will not live at the mercy of an outlaw regime that threatens the peace with weap- ons of mass murder. We will meet that threat now with our army, air force, navy, coastguard and marines so that we do not have to meet it later with armies of fire- fighters and police and doctors on the streets of our cities.” 8 Bush’s comments about fighting terrorists overseas so that Americans did not have to fight them within the United States became one of the administration’s main arguments for continuing military operations in Iraq after the fall of Saddam. Operation Iraqi Freedom In September 2002, the United States began to pre-deploy tanks and other mecha- nized vehicles in Kuwait for potential military action against Iraq. Ground forces were also deployed to the region, and the United States gained permission from the British to upgrade air force facilities on the island of Diego Garcia in order to base B-2 bombers there within striking distance of Iraq. By November, the United States had four aircraft carrier battle groups in the region. Two additional battle groups were dispatched in January 2003. Operation Iraqi Freedom 93 Iraqi Preparations In preparation for a potential invasion by the United States and its allies, the Iraqi government divided the country into four regions, each under the personal command of one of Saddam’s closest allies or relatives. At the time, Saddam was more concerned with an internal revolt than an external invasion. Conse- quently, he concentrated forces near the autonomous Kurdish areas and in the Shiite regions of southern Iraq. Saddam also deployed units along the border with Iran for fear that Tehran might attempt to take advantage of coalition military action to invade Iraq. - eBook - PDF

America's Wars

Interventions, Regime Change, and Insurgencies after the Cold War

- Thomas H. Henriksen(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

5.3 Operation Iraqi Freedom: America’s Cakewalk War Twelve hundred miles from George Bush’s bête noire in Baghdad, the Afghan war was heating up. There was something Napoleonic to starting another war before finishing the old one. Fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq was also accompanied by a growing worldwide conflict against terrorism. Stealth and secrecy defined this war known for its below-the- radar drone strikes and commando-style raids by America’s shadowy Special Operations Forces in the Philippines, Somali, Yemen, and other states. None of these smaller hostilities greatly suffered from Washington’s re-focus to Iraq as did Afghanistan. Long before soldiers rushed forward and battle tanks clanked in a second war on Iraq, American and British warplanes obliterated targets below their wings. The Anglo-American air forces had patrolled over northern and southern no-fly zones since the end of the Persian Gulf War. These air incursions, as related in Chapter 2, were to protect first the Kurds in northern Iraq and then later, and much less effectively, the Shiite population from the Iraqi dictator’s murderous police. The zones prohibited Iraqi flyovers. Over the following decade, the warplanes strafed radar installations and missile batteries on the ground. In the lead-up to Operation Iraqi Freedom, the Pentagon and the Royal Air Force accelerated their continuous bombing campaign. From June 2002 until the American-led invasion started, the Anglo-American pilots flew over 21,000 sorties and struck 349 terrestrial targets, encompassing air defense installations, command-and-control nodes, and fiber-optic communication networks. In the course of the first days of intense land warfare, the air campaign turned on Hussein’s army with some 1,800 airplanes on station. From 146 The Iraq War this armada, the coalition lofted some 1,000 warplanes in the air each day. - eBook - PDF

Saving Soldiers or Civilians?

Casualty-Aversion versus Civilian Protection in Asymmetric Conflicts

- Sebastian Kaempf(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Louis, Missouri’ Voice of America News. 204 The US War in Iraq a nation’, the US President’s rhetoric confirmed the importance attached to conducting a surgical military operation that was respectful of the principle of non-combatant immunity. With hindsight it might be easy to dismiss these optimistic accounts, especially given the subsequent course of the situation in Iraq after May 2003. But at the time when the planning phase for OIF took place, the Bush Administration understood its operations in Afghanistan not only as a success story (the Taliban had been overthrown, US forces had been largely withdrawn, an interim government installed, and recon- struction was underway) but also as a blueprint for how to embark on the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. How, then, did OIF unfold and to what extent were US forces able to wage this first combat phase with low risks to both US military personnel and Iraqi civilians? And how did the strategy of Saddam’s forces impact on the normative balance between US casualty-aversion and civilian protection? The Toppling of Saddam’s Ba’athist Regime (19 March–1 May 2003) The airstrike on the Presidential Palace in Baghdad on 19 March 2003 marked the opening shot of what was largely a conventional interstate war between the US-led ‘Coalition of the Willing’ and the military forces of the Iraqi state. The following day, US ground forces moved into southern Iraq, occupied the Basra region and engaged in the Battle of Nasiriyah on 23 March 2003. US Special Forces launched an amphibious assault from the Persian Gulf to secure the oil fields while the 173rd Airborne Brigade was dropped near the city of Kirkuk where they joined Kurdish rebels to fight the Iraqi army in the north. Massive airstrikes across the country and against Iraqi command and control centres threw the defending army into chaos and prevented an effective resistance against invading coalition ground forces. - eBook - PDF

How Wars Are Won and Lost

Vulnerability and Military Power

- John A. Gentry(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

CHAPTER 6 The U.S. War in Iraq (2003–2011) On March 19, 2003, the United States and its partners invaded Iraq for purposes of deposing President Saddam Hussein, thereby eliminating the perceived threat he posed to U.S. interests, finding and destroying Iraq’s WMD programs, and establishing a new Iraqi government that Presi- dent George W. Bush expected to be democratic, peaceful, and Western- oriented. 1 Bush hoped the new Iraq would be a model for political reform in the Muslim world and would not threaten Israel. Achievement of the first goal required only part of what was widely described as the finest conventional military force ever created. In a television spectacle, U.S. troops helped Iraqis topple a statute of Saddam in Baghdad on April 9. Although mopping up operations continued for several more days, the “war” was won within a month. The second goal evaporated when it be- came clear that Iraq destroyed its WMD stockpiles before 2003 while re- taining residual WMD production capabilities. The third, far more ambitious, objective required building a new Iraqi state. But it was not one that much concerned U.S. planners before April 2003. Senior civilian officials and military officers believed most Iraqis would welcome U.S. troops, that a coherent Iraqi government would nearly spontaneously reemerge, and there would be no internal Iraqi discord that would threaten U.S. troops or the nascent Iraqi democracy. It was not to be. U.S. planning assumptions proved to be nearly wholly wrong. 2 Despite its initial successes, the United States soon became bogged down in a counterinsurgency (COIN) war. After April 2003, the military task required skills the U.S. military previously denigrated and which Bush, like several presidents before him, showed little interest in - eBook - ePub

Security in the 21st Century

The United Nations, Afghanistan and Iraq

- Alex Conte(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Operation Iraqi FreedomIntroduction

The intervention in Iraq in 2003 has been a matter of considerable controversy, both prior to the commencement of operations and since the intervention in light of the failure of coalition forces to find weapons of mass destruction within the Iraqi territory, and allegations of faulty intelligence and misleading public statements by State officials. Many issues arise out of the war, including the basis upon which States may use force against one another; the effectiveness of the various international instruments governing the non-proliferation and disarmament of weapons of mass destruction; the conduct of military operations in the field; the role of the United Nations and others in post-war reconstruction; the accuracy or otherwise of military intelligence used by leaders to justify action against Iraq; and the role and relevance of international law in modern politics. All are important. All have an impact on the maintenance of international peace and security. The focus of this chapter, however, is a limited one and considers an important aspect of the overall theme of this text: the role of the Security Council in maintaining international peace and the exclusivity of that role.1Of the various key issues arising from the 2003 intervention in Iraq, the basis upon which States may use force against one another has attracted significant attention. Various arguments might be employed in an attempt to validate the action against Iraq, It might be argued, for example, that intervention was permissible as an act of anticipatory self-defence, in the face of intelligence suggesting that Iraq was in a position to launch weapons of mass destruction at 45 minutes notice. This would have to be tempered against the subsequent finding by the United Kingdom Parliamentary Foreign Affairs Committee on 7 July 2003 that a dossier on Iraq's weapons, relied upon by Prime Minister Blair in his address to Parliament on 18 March 2003, was incorrect. The contention would also need to reflect upon the legal arguments that neither the United Nations Charter, nor customary international law, permit anticipatory self-defence.2 A more controversial position might also have been posited: that action was permissible by way of humanitarian intervention, due to the dreadful human rights record of the Saddam regime.3 - eBook - PDF

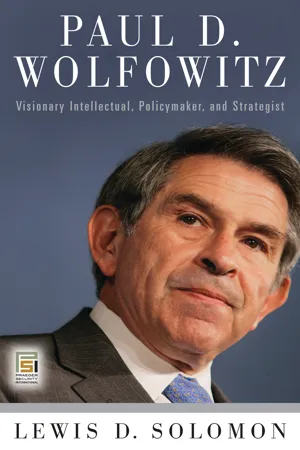

Paul D. Wolfowitz

Visionary Intellectual, Policymaker, and Strategist

- Lewis D. Solomon(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

Chapter 7 The Road to Baghdad, Part Three: Operation Iraqi Freedom From early 2001 until Operation Iraqi Freedom in March 2003, the Bush White House debated what to do about Saddam Hussein’s regime. In a post-9/11 world, the use of force as a proactive tool to effectuate regime change replaced a reliance on containment. Since the 1986 regime shift in the Philippines, Wolfowitz had sought to spread democracy overseas. After 9/11, he focused on seeding democratic ideals in the Middle East in order to undercut the repressive societies from which terrorist organizations could recruit their forces. As an outspoken advocate for removing Saddam, he held firm to his belief in Iraq’s democratic potential. Transforming Iraq and the Middle East generally would require a long-term commitment by the American public. Unfortunately, as chapter 8 will demonstrate, the Bush administration, including Wolfowitz, underestimated the difficulty of regime change in Iraq, a nation marked by sectarian rivalries, ethnic feuds, and ancient grudges. SOME BACKGROUND ON IRAQ AND ISLAM Modern Iraq is a artificial construct of diverse tribal and religious groups put together in 1920 as a League of Nations mandate under British control. 1 It consists of three provinces from the defunct Ottoman Empire: Mosul in the north; Baghdad in the center; and Basra in the south. Commerce linked Mosul to Turkey and Syria; the non-Arab Kurds in the north were mostly Sunni Muslims. The Sunni Arabs were concentrated in the west. In and around Baghdad the population was a mix of Shiite and Sunni Arabs. Shiite Arabs dominated the southern cities of Najaf, Karbala, and Basra, with Najaf and Karbala, Shiite shrine cities, oriented toward 86 Paul D. Wolfowitz Persia. Those in and around Basra looked to commerce with India. Ethnic Turks and Assyrian Christians were found scattered throughout the mandate.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.