History

Rock n Roll

Rock 'n' Roll is a genre of popular music that originated in the United States in the late 1940s and early 1950s. It is characterized by a strong rhythm, simple melodies, and often rebellious lyrics. Rock 'n' Roll has had a significant impact on popular culture, influencing fashion, attitudes, and language, and has been a major force in shaping the development of youth culture.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Rock n Roll"

- eBook - ePub

When Genres Collide

Down Beat, Rolling Stone, and the Struggle between Jazz and Rock

- Matt Brennan(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Academic(Publisher)

In the mythology perpetuated by such accounts, the roots of rock ‘n’ roll were a blend of musical sources: African-American rural country blues and urban rhythm and blues, hillbilly country and western music, and polished pop from Tin Pan Alley. According to music historian Chris McDonald, if jazz gets acknowledged at all in this framework, it is often positioned within a “simplified, perhaps caricatured, image of Tin Pan Alley, which gets portrayed as an exclusively white, middle-class milieu, somehow isolated from the diversity and turbulence of the larger American society.” 3 Some scholars have challenged the common-sense blues + country + pop representation of the roots of rock ‘n’ roll. Gene Santoro, for example, proposes that American popular music history should be understood as a tangled web of interactions between jazz, blues, country, and rock, while Philip Ennis argues that at least six distinct musical streams contributed to the formation of rock ‘n’ roll: pop, black pop, country pop, jazz, folk, and gospel. 4 However, more often than not, jazz culture — with its connotations of big bands and dance ballrooms — is represented as the musical culture from which rock ‘n’ roll broke away. Chris McDonald suggests that jazz and its culture are left out as an influence on rock ‘n’ roll for another reason as well: jazz criticism and scholarship has been so invested in raising jazz’s status to an art music that its most commercial [pre-World War II] forms have been given little serious coverage. On the other hand, many popular music scholars have been invested in portraying rock and roll as a “revolutionary” genre, and have therefore sought to show disjuncture, not parallels, with popular music from before 1950. 5 This chapter makes the case for the importance of jazz as a key cultural precursor to rock ‘n’ roll - eBook - PDF

Mexican American Mojo

Popular Music, Dance, and Urban Culture in Los Angeles, 1935–1968

- Anthony Macías, Ronald Radano, Josh Kun, Ronald Radano, Josh Kun(Authors)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Duke University Press Books(Publisher)

In its early years, rock and roll was also called ‘‘the big beat,’’ due to its simplified, hard-driving 2/4 rhythm with the accent on the back beat. Lyrically, many of the new songs would abandon the mature themes of the blues and R & B for references to adolescence and innocent love. ∞ Still, the ascendance of rock and roll as the music of choice for the nation’s young consumers, both urban and suburban, led to what one historian calls ‘‘a profound shift in cultural values on the part of main-stream youth’’ toward African American sensibilities. Postwar economic prosperity allowed more people to buy into the status-symbol commod-ity lifestyle of the middle classes, producing unprecedented leisure time and disposable income for baby boom teenagers. Yet American workers’ ‘‘happy middle-class existence’’ and newfound ‘‘aΔuence concealed an unrewarding lifestyle,’’ hence their suburban children were drawn to the music’s spirit and energy. ≤ Indeed, as popular music, rock and roll con-tained enough residual elements of the ribald, roughneck boogie woogie and jump blues styles to counterbalance the values of the regimented, bureaucratic dominant culture. Robert Palmer argues that ‘‘as a musical idiom’’ the new genre contained ‘‘a spark of freshness, an attitude of adventure and exploration.’’ ≥ At first, ‘‘with its sexuality and blackness,’’ it ‘‘brought out fears of miscegenation,’’ but the music quickly came to sym-bolize youthful white rebellion, particularly after teen-targeted Hollywood films like Blackboard Jungle (1955) and Rock around the Clock (1956) be-came hits, and after Elvis Presley was dubbed the ‘‘King of Rock and Roll.’’ ∂ The African American slang term rock and roll had long described sexual intercourse in blues lyrics. In that tradition, Jimmie Lunceford recorded a song called ‘‘Rock It for Me’’ in 1939, while Cab Calloway recorded ‘‘I Want to Rock’’ in 1942, and in the mid- to late 1940s, the word - eBook - PDF

Popular Music in America

The Beat Goes On

- Michael Campbell(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

Freed had moved to New York the previ-ous year in order to offer his rock-and-roll radio show on WINS. Because both performers and audience had such rec-ognizable identities, it was easy—even natural—to lump all the music that teens (and many African Americans) listened to under one banner. However, during the latter half of the 1950s, rock and roll and rhythm and blues diverged. The first—and easiest— distinction between them was racial: Rock and roll usually featured white performers and catered to a white audience; rhythm-and-blues artists were black, and so was their core audience. But this method, although accurate up to a point, was fundamentally flawed. Several important rock and roll artists—above all Chuck Berry, the architect of the sound of rock and roll—were African Americans. By 1957, it was possible to make a clear musical distinction, one that helps explain why we consider the music of Berry and Little Richard to be rock and roll, not rhythm and blues. In this unit, we trace the musical evolution of rock and roll. Copyright 2019 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 172 UNIT 11 ● Rock and Roll money inevitably led to the emergence of the new teen subculture. Teens defined themselves socially, economically, and musically. “Generation gap” became part of everyday speech. So, unfortunately, did “juvenile delinquent.” Teens put their money where their tastes were, and many had a taste for rock and roll. - eBook - PDF

- Lisa Jo Sagolla(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

In 1920s “race” music, the words “rock” and “roll” had been used separately to refer to sex, but by the ’30s and The Detonation of Rock ‘n’ Roll Music 7 ’40s, “rock and roll” had come to refer to a rhythmic sensuality con- tained in the era’s swing music. In the 1934 film Transatlantic Merry-Go- Round, the vocal trio The Boswell Sisters sang “Rock and Roll,” a song about a type of Swing dancing. Some rhythm and blues songs of the early 1950s, however, made use of variations of the words “rock- ing” and “rolling” as sexual innuendos. 15 But whatever its connota- tions or origins, the term “rock ‘n’ roll” quickly came to mean the kind of music being heard on Freed’s radio show. And record companies soon started using the term as the name of a category of music aimed at Amer- ica’s youth. While it is virtually impossible to pinpoint exactly when, by whom, or in what song the musical fusion of rock ‘n’ roll was first heard, the cover version of “Rock Around the Clock,” released on May 10, 1954, by Bill Haley & His Comets is often heralded as the start of the rock ‘n’ roll phenomenon. “Cover” is a term used to describe a recording of a song made by an artist other than the one who originally recorded it. Covers are gen- erally made with the intention of allowing a song to be marketed to Alan Freed, the disc jockey and concert producer who sparked the popularization of rock ‘n’ roll. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images) 8 Rock ‘n’ Roll Dances of the 1950s an audience that the original version could not or would not reach. White artists’ bowdlerized cover versions of songs originally recorded by black performers played a big role in the early history of rock ‘n’ roll, when it was thought that the distinctively “black” vocal sounds or naughty lyrics would compromise the music’s marketability to audi- ences outside the African-American community. - eBook - PDF

- Fabian Holt(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- University of Chicago Press(Publisher)

Rock and Roll and Popular Music Landscapes in the 1950 s Chapters 3 – 4 examine the problematic outlined above through a compara-tive study of reactions to rock and roll in country music and jazz in the mid 1950 s. For reasons that will be obvious later, the case study of jazz will also a model of genre transformation 57 look at reactions to the boom in the mid 1960 s when the dominant term for the emerging genre became rock music. When rock and roll emerged, coun-try and jazz had just become established as genres with a canon, and that constitutes some common historical and structural ground for comparisons between two genres associated with different places and social groups. In both case studies, the focal point will be the first style that emerged in response to rock music (including 1950 s rock and roll) and was motivated by crossover interests. I have chosen this strategy because reactions to rock were strongest and most visible at the time when it was perceived to cause a new wave of influence from outside and change the general situation in the genre. This strategy also allows us to deal directly with musical and not only social and discursive reactions. The mid 1950 s was a time of decline for the culture of live swing music and dancing. Many of those who had been involved in it during the 1930 s and 1940 s were now making television the primary medium of family en-tertainment. A teenage market emerged with films like Rock Around the Clock ( 1956 ) and the Top 40 radio format. Top 40 operated with playlists that were basically dictated by the Billboard charts, and they included only music that was expected to have a broad appeal to the newly record-buying teenagers. This was particularly hard on genres with a small market because they did not attract advertisers. - eBook - PDF

Is It Still Good to Ya?

Fifty Years of Rock Criticism, 1967-2017

- Robert Christgau(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Duke University Press Books(Publisher)

Enter rock and roll, which has now prevailed in its many guises for nearly half a century. The standard oversimplification, which declares rock the bas-tard child of blues and country, ignores the pop savvy of its overseers and exaggerates the whiteness of its roots, but does serve to emphasize its proud dependence on the modal melodies and small-group dynamics that drove country and r&b. In addition to these essential attractions, rock privileged three elements that had been knocking on pop’s door since 1900: youth, race, and rhythm. Pop music had always been youth music, never more than in the ’30s, but ’50s teendom—enjoying an explosion of spending cash as it resisted a resurgent nuclear-family ideology out of step with too many other realities—was far more sure of itself than earlier youth cultures. And though American music has always been crossbred and American culture has never stopped being racist, the integration of pop in the ’50s was far more drastic than anything suggested by the Mills Brothers on the hit parade. Of course whites maintained economic control and configured dozens of rock subgenres to their preferences and expectations—often to excellent effect, too. It’s even conceivable that all of rock’s radical racial metaphors were epiphenomena of the civil rights struggle. But it’s crude reductionism to charge, for instance, that hip-hop’s pop reach is blackface all over again. African-American musi-cians exert a status and power denied them fifty years ago. To prove it, there’s rhythm. Since minstrelsy at the latest, the basic story of American and then world popular music had been cheap tunes getting their beats ragged. But the tunes, arguably part African themselves, re-mained paramount. With rock the balance shifted—Elvis and Chuck Berry, who had nothing on Jerry Lee Lewis and Bo Diddley, stressed and isolated the beat as even Count Basie’s riff-heavy rhythm kings had not. - eBook - PDF

Sexual Reckonings

Southern Girls in a Troubling Age

- Susan K. Cahn(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Harvard University Press(Publisher)

Today adolescents dictate musical cul-ture, so to speak, to the rest of us.” 14 While the New York Times in-quired simply, “Is this generation going to hell?” another critic de-scribed his experience at a rock show as “like attending the rites of some obscure tribe whose means of communication are incompre-hensible.” Furthermore, “teenagers of all races have fallen under its spell . . . Rock ’n’ roll is their own, and they love it.” 15 Although adults found rock ’n’ roll confusing, many worried that teenagers found a message not only comprehensible but reprehensible as well, with performers and audiences communicating a willingness to disregard conventional rules of propriety. Alarmed music critics, in-dustry insiders, parents, local civic groups, ministers, and political of-ficials registered their opposition in numerous ways. While music crit-ics issued scathing reviews, denouncing the music as monotonous and crude and the performers as untalented shouters completely lacking in talent, other experts tried to untangle the social pathology they heard in the music. They pointed first to rock ’n’ roll’s black roots. Described as having a “jungle strain” that appealed to all races, rock ’n’ roll raised hackles about racial mixture in the music and its fan base. 16 Time magazine described rock ’n’ roll as “based on Negro blues, but in a self-con-scious style which underlines the primitive qualities of the blues with malice aforethought.” The malice, apparently, consisted of “violent” sounds that struck the listener like a “bull whip” or a “honking mating call,” eliciting in fans “rings and shrieks like the jungle-bird house at the zoo.” 17 The references to malicious violence and primitive animal sounds echoed many other assessments that linked rock to “primitive” Africa or its African American descendants, even when performed by white musicians. - eBook - ePub

Major Labels

A History of Popular Music in Seven Genres

- Kelefa Sanneh(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Canongate Books(Publisher)

Rolling Stone described a different pamphlet (or possibly the same one), distributed at a different Rolling Stones concert, making a connection between the band’s putative sexism and its broader failure to be inclusive. “Rock music should be everyone’s music,” the pamphleteers wrote. “Rock culture should be everyone’s culture.” Certainly musical segregation tended to harm the professional prospects of Black musicians, who typically found R&B stardom less lucrative than the rock ’n’ roll equivalent. And certainly there were plenty of Black musicians making brilliant rock-inspired music in the seventies, ranging from Sly Stone to George Clinton to Chaka Khan. But to classify them as belonging to the rock ’n’ roll world, instead of the R&B world, would be to enrich rock ’n’ roll and impoverish R&B. Would that be an improvement? It is fair to object that musicians can (and usually do) work in more than one genre. But it also seems important not to distort the reality of the seventies, during which the world of rock ’n’ roll was in many ways less integrated than it had been before.When rock ’n’ roll split from R&B, in the sixties, it lost much of its Black audience, and therefore its pretension to universality—it could never again claim to be the sound of America. Not coincidentally, rock ’n’ roll lost its horns around the same time: the saxophone, once an integral part of the rock ’n’ roll sound, was nearly gone from the genre by the early seventies, except for the occasional solo. Now the dominance of guitars was total, and the electric guitar was more and more perceived as a “white” instrument. Seventies rockers tended to be self-conscious about their position as white stars in a genre with an illustrious Black history. The Rolling Stones returned endlessly to the blues masters who inspired them and sometimes made a point of touring with Black opening acts. (It is possible to hear “Brown Sugar,” the band’s much-loved and much-loathed song about slavery and interracial sex, as an autobiographical allegory: the story of white British musicians whose “cold English blood runs hot” when they hear Black American music.) But some rock bands pushed the other way, eager to carve out a musical identity for rock that would be independent of its roots in blues and Black music. Critics sometimes used “blues” as an insult, shorthand for plodding and predictable instrumental passages. A perceptive writer known as Metal Mike Saunders, who championed heavy bands, praised Led Zeppelin II for taking “a crucial first step away from blues and excess jerkoff solos”; a review of Fleetwood Mac in Rolling Stone noted with approval that the group had moved away from “laborious blues/ rock jams”; Time, in its 1974 explanation of heavy metal, defined the genre as “heavy, simplistic blues played at maximum volume.” Disparaging the blues became a way for rock stars to portray themselves as modern, or honest. In 1978, Tom Petty, who was just starting to be celebrated for his tough and tart rock ’n’ roll, told Sounds, a British magazine, “I never really copped to the blues,” although he did express admiration for old R&B records. And in an interview in BAM, a San Francisco rock magazine, Alice Cooper, the vampire-drag hard rocker, explained his disdain for the blues in demographic terms. “We’re not going to play Delta Blues,” he said. “I don’t give a damn about how many times his baby left him. We’re upper middle-class suburban brats that had anything we wanted. We never had - eBook - ePub

MusicQuake

The Most Disruptive Moments in Music

- Robert Dimery(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Frances Lincoln(Publisher)

THE RISE OF ROCK’N’ROLL

1954–1966

The post-war era was defined by clashing ideologies, the threat of conflict and racial unease. All of which was reflected in the music of the moment, which became more politicized.After years of injustice, segregation was declared illegal by the US Supreme Court in 1954 – the year Elvis Presley made his first recordings – but it remained a fact of life in Southern states, and musicians would become part of complex cultural debates. Elvis Presley and his rock’n’roll brethren were pilloried by some for embracing ‘coloured’ musical styles; others would claim he had a role in uniting whites and Blacks. (‘The white kids had to hide my records ’cos they daren’t let their parents know they had them in the house,’ recalled Little Richard.) Elsewhere, two white Jewish songwriters, Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, penned imperishable tracks for Black performers such as Big Mama Thornton and the Coasters (and eventually Elvis himself).In 1955, after Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white man in Montgomery, Alabama, there was a city-wide bus boycott. By the early 1960s, such ‘Freedom Rides’ were a common strategy for the burgeoning civil rights movement, which had the inspirational Reverend Martin Luther King Jr as one of its leading lights. In the early 1970s, Motown’s Berry Gordy Jr would release speeches by King, and spoken-word pieces by activist Stokely Carmichael and poets Langston Hughes and Margaret Danner on his Black Forum label.In tandem, a revival of folk music in America that had begun in the 1940s acquired new urgency and impetus with the rise of singer-songwriters including Bob Dylan, Joan Baez and Phil Ochs. Touted (though it irked him) as the voice of his generation, Dylan offered caustic commentary on discrimination, nuclear armageddon and sabre-rattling with instant anthems such as ‘Oxford Town’, ‘Talking World War III Blues’ and ‘Masters of War’. - eBook - ePub

The Classic Rock and Roll Reader

Rock Music from Its Beginnings to the Mid-1970s

- William E Studwell, David Lonergan(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Transatlantic Merry-Go-Round,starring Jack Benny. (This meaningless linking of Benny and his low-key humor with rock and roll and its less than subtle style seems a bit out of place and somewhat ridiculous.)Although Freed popularized the phrase before “Shake, Rattle and Roll” and “Rock Around the Clock” were recorded, the great success of both helped turn what could have been a temporary music fad into a full blown music industry. “Shake” and “Rock Around” did not invent the phrase “rock and roll,” but did much to imprint the concept into the minds of the American public. In a real way, then, “Rock Around the Clock” was the lasting inspiration for the term “rock,” and “Shake, Rattle and Roll” the lasting inspiration for the term “roll.”Passage contains an image

Older-Style Songs Amidst the Rocks

DOI: 10.4324/9781315786490-4All the Way

There was a “rock revolution” in the mid-1950s, or more exactly, a shift in the style of popular music. But the emergence of rock did not mean that earlier style songs totally disappeared from the popular scene. In fact, even in the period of hard rock and rap after the mid-1970s, sentimental ballads and other older style compositions still continued to be created and flourish. One of the reasons that the term “rock revolution” is somewhat misleading is that it suggests a more or less total upheaval of earlier musical styles. Such is not true. Rock did alter artistic patterns, but did not go all the way and annihilate other pathways to the hearts of the American public.In reality, early rock was rather benign, although many older people probably didn’t think so. The first years of rock were rather frantic ones in the history of American culture, but there was plenty of room for opposing creative viewpoints. For example, Frank Sinatra continued in his old ways with much success. From the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s, Sinatra had several top hits that were not in rock style. Teaming up with lyricist Sammy Cahn and composer Jimmy Van Heusen, Sinatra recorded their “Love and Marriage” (1955), “The Tender Trap” (1955), “Come Fly with Me” (1958), “High Hopes” (1959), “The Second Time Around” (1961), “My Kind of Town” (1964), and “All the Way” (1957). Singing these pieces, and many others, Sinatra remained somewhat popular all the way into the 1990s. - eBook - PDF

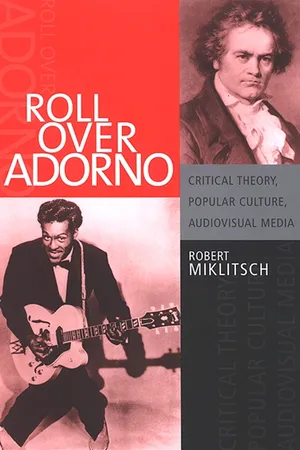

Roll Over Adorno

Critical Theory, Popular Culture, Audiovisual Media

- Robert Miklitsch(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- SUNY Press(Publisher)

25 1 Rock ‘n’ Theory Cultural Studies, Autobiography, and the Death of Rock T his chapter is structured like a record— a 45, to be exact. While the A side provides an anecdotal and autobiographical take on the birth of rock (on the assumption that, as Robert Palmer writes, “the best histories are . . . personal histories, informed by the author’s own ex- periences and passions” 1 ), the B side examines the work of Lawrence Grossberg, in particular his speculations about the “death of rock,” as an example or symptom of the limits of critical theory when it comes into contact with that je ne sais quoi that virtually defines popular music (“It’s only rock ’n’ roll, but I like it, I like it!”). By way of a conclusion, the coda offers some remarks on the generational implications of the discourse of the body in rock historiography as well as, not so incidentally, some crit- ical comments on the limits of the autobiographical narrative that makes up the A side. A Side: The Birth of Rock, or Memory Train Don’t know much about history. —Sam Cooke, “Wonderful World” In 1954, one year before Bill Haley and the Comets’ “Rock around the Clock”—what Palmer calls the “original white rock ’n’ roll” song— became number one on the pop charts, marking a “turning point in the history of popular music,” 2 and one year before Elvis covered Little Junior Parker’s “Mystery Train” (then signed, under the self-interested tutelage of Colonel Parker, with RCA), in 1954—the same year the Supreme Court ruled racial segregation unconstitutional—the nineteen- year-old and still very much alive Elvis Presley walked into the Mem- phis Recording Service and cut Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup’s “That’s All Right.” This is Elvis recollecting Phillips’s phone conversation with him: “You want to make some blues?” Legend has it that Elvis hung up the phone, ran fifteen blocks to Sun Records while Phillips was still on the line .

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.