History

Safavid Empire

The Safavid Empire was a Persian dynasty that ruled Iran from 1501 to 1736. It is known for its promotion of Twelver Shia Islam as the state religion and for its significant cultural and artistic achievements, including the development of Persian literature, art, and architecture. The empire also engaged in conflicts with the neighboring Ottoman Empire and Mughal Empire.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Safavid Empire"

- eBook - ePub

- Jim Masselos, Jonathan Fenby(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Thames and Hudson Ltd(Publisher)

CHAPTER FIVE Persia: The Safavids 1501–1722 SUSSAN BABAIE T he Safavid Empire of 1501–1722 was the longest-lasting Persian polity in the history of Islamic Iran. Its alignment of ancient Persian ideas of kingship with Imami Shia doctrines of Islam created a distinctive culture whose powerful legacy can be traced in the later history of the region. 1 The Safavid Empire grew out of a messianic venture in the north west of Persia, which became the anchor for the reemergence of a distinctly Persian empire not seen since the advent of Islam in the 7th century. Imami or Twelver Shiism (named for the twelve Shia imams) became the dominant religion, although Sunni Islam was prominent along with large communities, native or imported, of Zoroastrians, Jews and Christians. The territorial gains and losses of the Safavid period settled to an area more or less contiguous with the political boundaries of modern Iran. The Persian and Shia cultural identity of the Safavid Empire grew out of continual conflict or competition with neighbouring Sunni empires – the Ottomans, the Mughals and the Uzbeks – and political alliances and trade partnerships with Europe and Asia. A cultural synthesis, forged out of the ethnic, linguistic and religious groupings in Safavid society, revived the political concept of Iran, rooted in its long history, as a proto-nationalist phenomenon. 2 The Boy Becomes King ‘The padshah [king] of the inhabited quarter of the globe’ 3 was the fourteen-year-old Ismail (1487–1524), the charismatic young leader of the Safaviyye order. This was one of the numerous Sufi (mystical) orders that arose in western Asia in the wake of the Mongol invasions of the early 13th century. The order was founded by Sheikh Safi al-Din Eshaq (1252–1334) and centred on a shrine complex at Ardabil, near the south-western shore of the Caspian Sea. Leadership of the order was inherited; Ismail was a direct descendant of Sheikh Safi (a ‘Safavid’) - eBook - ePub

Islamic Gunpowder Empires

Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals

- Douglas E. Streusand(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Chapter 4 The Safavid EmpireT he Safavid Empire never equaled the size, power, or wealth of the Ottoman or Mughal empires. Its history had a different pattern. It did not grow steadily over many decades but reached its maximum size within a few years of its foundation and maintained those boundaries only briefly. Safavid rule transformed the religious life of the empire but had a much less significant effect on its ethnic composition and social structure. Some historians have questioned whether it qualifies as an empire at all, though the Ottomans and Mughals had no difficulty identifying the Safavids as peers. The Safavid polity began as a confederation of Turkmen tribes, led not by the leader of one tribe but by a Sufi shaykh , Ismail Safavi (I use the anglicized Safavid for the order and dynasty but Safavi in personal names). The Safavid ideology—a blend of ghuluww , Turko-Mongol conceptions of kingship, and the folk Sufism of the Turkmen—energized the tribes. This ideology and Ismail’s consistent military success from 1501 to 1512 suspended the normal political operation of the tribal confederation. After the first Safavid defeats, at Ghujduvan in 1512 and Chaldiran in 1514, Ismail’s loss of prestige altered the balance of power within the confederation, giving the tribal leaders decisive authority and making their struggle for dominance the central issue in Safavid politics. After 1530, Ismail’s son, Shah Tahmasp, gradually strengthened his position enough to manipulate, rather than be manipulated by, the tribes. After his death, however, the tribal chiefs again dominated the empire until the time of Abbas I (1588–1629). Abbas transformed the Safavid polity from a tribal confederation into a bureaucratic empire. The primacy of the bureaucracy, with the tribes present but peripheral, survived until the rapid collapse of the empire in 1722.Map 4.1 Safavid EmpireThe Ottoman and Mughal empires clearly deserve the title agrarian. They represented transplants of the agrarian bureaucratic traditions of the Middle East to rich agrarian regions elsewhere. The Safavids had no such advantage; the tribal resurgence in the eighteenth century showed that the ecology of the Iranian plateau continued to favor pastoral nomadism. The Safavid regime relied not on broad agricultural prosperity or control of major trade networks but on the export of a single commodity: Abbas I’s central army and central bureaucracy depended on income from the export of silk. The Safavid polity thus became a gunpowder empire because of the increase in global trade in the sixteenth century. Otherwise, the Safavid Empire, in all probability, would have remained a tribal confederation, held only the central and western parts of the Iranian plateau, and had a shorter lifespan. The income from this commerce did not, however, permit a return to the previous agrarian pattern of Abbasid times, based on massive irrigation works. The empire thus became a peculiar hybrid. Under Abbas I, the center became strong enough to reduce the Qizilbash tribes to political insignificance but could not eliminate them. There was no open frontier to divert them to. When the central regime failed, the tribal forces became dominant by default. - eBook - PDF

History of civilizations of Central Asia, v. 5

Development in contrast, from the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century

- Adle Chahryar, Habib Irfan, Baipakov Karl M.(Authors)

- 2003(Publication Date)

- UNESCO(Publisher)

. . . . . . . . . . 273 * See Map 5, p. 925. 250 ISBN 978-92-3-103876-1 The birth of an empire . . . Part One THE SAFAVIDS (1501–1722) The birth of an empire and the emergence of present-day Iran The formation of the Safavid state at the beginning of the sixteenth century is one of the most important developments in the history of Iran. It may indeed be seen as the start of a new era in the political, cultural and social life of modern Iran, the creation of an alternative state, one based on centralized power and the establishment of Shi c ism as the official faith, with borders broadly corresponding on the west (the Ottoman empire) and the south (the Persian Gulf) to those of the present-day Islamic Republic of Iran. The position of the Safavids as a great power contemporary with the Mughal empire in India, and the Ottoman empire in the Middle East, played a role in the shaping and functioning of political powers not only in southern and western Asia, but also indirectly in Europe. Sh¯ ah Ism¯ a c ¯ ıl I founded the Safavid state in 1501 as the result of a long process of devel- opment that had begun almost two centuries earlier when his ancestor, Shaykh Saf¯ ı’udd¯ ın Ardab¯ ıl¯ ı, had set up the kh¯ anaq¯ ah (dervish convent) of his spiritual order in Ardabil (Azarbaijan) during the period of the Ilkh¯ anids. 1 Shaykh Saf¯ ı died in 1334, and from then until the time when Sh¯ ah Ism¯ a c ¯ ıl came to power, the leadership of the Safavid order was maintained on the basis of hereditary succession. During this period, which lasted for 113 years, many people from Azarbaijan, Aran and Anatolia joined the mur¯ ıds (follow- ers) of the kh¯ anaq¯ ah of Ardabil, and this greatly increased the spiritual authority of the order. When Shaykh Junayd assumed the spiritual leadership (1447–60), the outlook of the kh¯ anaq¯ ah, which until that time had been based on Sufi teachings, underwent a transfor- mation with the adoption of a policy of intense Shi c ite proselytism. - eBook - PDF

Modern Iran since 1797

Reform and Revolution

- Ali Ansari(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

6 This is certainly reflected in the nature of the empire itself, which incorporated and indeed tolerated a num- ber of different faiths. Later Safavid monarchs, scions of Circassian concubines who emanated from the Christian heartlands of the empire in the Caucasus, appeared to have been quite open-minded about the religious beliefs of their subjects. 7 This was by no means a sectarian empire with totalitarian intent, even if it inflicted the occasional pogrom. The seventeenth-century Safavid state, the product of Shah Abbas’ reforms, thus drew on Persian, Islamic and perhaps to a decreasing extent Turkic sources of legitimacy – a cosmopolitan inheritance for a cosmopolitan empire. Shah Soleiman I, the penultimate monarch was emblematic of this complex inherit- ance. The son of a Circassian mother he was described by Chardin as blond and blue eyed (although he dyed his hair black), 8 his first language was effectively Turkish, and his birth-name was Sam, the grandfather of the Persian (mytho- logical) hero, Rostam, and while his throne name was decidedly Muslim, his adherence to scripture was not. 9 Of the three ostensibly Muslim empires of the period, the Ottoman, Safavid and Mughal empires, the Safavid was neither the richest nor the most powerful, 22 The legacy of the eighteenth century but it certainly managed to hold its own, despite territorial losses to the Ottomans, and what it lacked in material power it made up for with cultural depth and reach. Both the Ottomans and the Mughals had connections to the Persianate world. The language of government in Mughal India was Persian providing in many ways for a fluid cultural zone in which men of letters moved and settled relatively freely. 10 While to the West the Turco-Iranian culture of the Ottoman Empire remained relatively accessible to the Turco-Iranians of the Safavid Empire. - eBook - PDF

Time in Early Modern Islam

Calendar, Ceremony, and Chronology in the Safavid, Mughal and Ottoman Empires

- Stephen P. Blake(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

1 Safavid, Mughal, and Ottoman Empires The three Islamic empires of the early modern period – the Mughal, the Safavid, and the Ottoman – shared a common Turko-Mongolian heritage. In all three the ruling dynasty was Islamic, the economic system was agrarian, and the military forces were paid in grants of land revenue. Despite these similarities, however, significant differences remained. And, to fully appreciate the individual temporal systems, a brief description of the political, economic, religious, and cultural conditions in each state is necessary. Within the confines of a single chapter, however, it is not possible to review all of the literature and settle all of the controversies. As a result, the brief overview that follows depends, for the most part, on the most recent general histories and surveys. Safavid Empire (1501–1722) Safavid Iran was shaped like a bowl, a flat bottom encircled by two mountain ranges. The Elburz Mountains ran along the southern shore of the Caspian Sea and met the smaller ranges of Khurasan in the east. The Zagros Mountains stretched from Azerbaijan in the northwest to the Persian Gulf and then east toward Baluchistan. The Eastern Highlands bordered the country on the southeast. A high arid plateau, with an average elevation of 3,000 feet, formed the base of the bowl. Two deserts – the Kavir and the Lut – sprawled across this expanse. Only three rivers interrupted the dry plateau: The Karun River (the only navigable one) originated in the Zagros Mountains and flowed to the Shatt al-Arab and the Persian Gulf; the Safid River rose in the Elburz Mountains and emptied into the Caspian Sea; and the Zayanda River, the only one of the three that 21 map 1. The Safavid Empire, c. 1660 watered the plateau, began in the Zagros Mountains and flowed through Isfahan, dying in a salty swamp nearby. No reliable estimates are available for the population of Safavid Iran. - No longer available |Learn more

Missionaries in Persia

Cultural Diversity and Competing Norms in Global Catholicism

- Christian Windler(Author)

- 2024(Publication Date)

- I.B. Tauris(Publisher)

2 In the Shadow of the Shah: The Safavid Empire as an Arena for Catholic MissionIn the sixteenth century, contacts between Europeans and Persians were few and far between. Europeans showed little interest in the region. What information was available was fragmentary and chiefly secondhand. European observers combined this small store of empirical information with the knowledge about ancient Persia that they had inherited from the Greeks and the Romans. Few Europeans traveled from India to the fort on Hormuz, which had been in Portuguese hands since the early sixteenth century, and onward into the Persian Gulf and the heartland of the Safavid Empire. Portuguese interests focused mainly on the coastal towns on the Persian Gulf, as is evident from the surviving written accounts and maps. The envoys the Portuguese governors of Hormuz and the viceroys of the Estado da Índia sent to the Safavid court beginning in 1514 received little attention in Persia. Contacts with other Christian courts remained episodes at best.1This situation of mutual indifference ended around 1600. News of the successes of ʿAbbās I’s troops against the Ottomans that were reaching the European courts fostered projects of an alliance with the shah. A variety of European expectations came to focus on the Safavid Empire. At the court of Philip III, king of Castile and Portugal, and at the Roman Curia, hopes arose of realizing a twofold dream: military victory over the Turks, the enemies par excellence of Christendom, and the conversion to Christianity of large numbers of Muslims.2 Around the same time, from the Indian Ocean, the English and Dutch discovered the Safavid Empire as a potential trading partner.On the Persian side, Shah ʿAbbās I (r. 1588–1629) was similarly searching for allies against the Ottomans. Moreover, his politics of empire-building created the structural conditions needed to enhance and solidify contacts with European courts and trading companies, as well as to attract Catholic missionaries. Indeed, Shah ʿAbbās I consolidated monarchical rule over a vast socioculturally and religiously heterogeneous empire, not only by expanding bureaucratic institutions and a mercenary army but also by integrating the various population groups into the court networks. - eBook - PDF

Persian Historiography

A History of Persian Literature

- Charles Melville(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- I.B. Tauris(Publisher)

That is, when Shah Esmâ’il and Shah Tahmâsp were in power, most of the existing chronicles were general histories to which the chronicler added either a final chap -ter or a separate section on the Safavids, thus portraying them as the latest in a succession of Islamic dynasties. Formative Safavid historiography, with its roots in the Timurid and Mongol tradi-tions, inherited Turko-Mongol legitimizing notions of universal rule. Such notions help explain the composition of earlier works such as Rashid-al-Din’s Jâme’-al-tavârikh . 53 By the time Shah Abbâs came to power, the Safavids had been in control of Iran for nearly a century. Shah Abbâs initially faced numerous challenges to his rule, including a very powerful group of Qezelbâsh who had reasserted their power before he came to the throne. Once Abbâs consolidated his rule, however, the Safavids became a major force on the international scene, engaging in war and diplomacy with neighboring Ottomans, Mughals, and Uzbeks. At the same time, various European powers had established trad-ing companies in Iran. Eventually, as the dynasty gradually began to appear more secure and unlikely to collapse, its historiography appears to have become less reliant on the pre-Safavid past. It had a well-established history, which had already undergone numerous revisions during the reigns of earlier Safavid kings, in particular Shah Tahmâsp. There was thus enough Safavid history to justify a lengthy volume devoted to the reigns of the Safavid kings alone. Some, such as Shah Tahmâsp, ruled for so long that it became to compile a substantial book solely on his reign. 54 Furthermore, pre-tensions to universal rule were less effective in an Islamic world divided into Ottoman, Mughal, and Safavid Empires. Newer Sa-favid legitimizing ideas, primarily based on principles of Twelver Shi’ism, become consolidated and gradually replaced Chengisid and Timurid notions of universal rulers. - eBook - PDF

Remapping Travel Narratives, 1000-1700

To the East and Back Again

- Montserrat Piera(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Arc Humanities Press(Publisher)

Keywords: Safavid, word and image, Shi‘ite, travel literature At tHe Beginning of the seventeenth century, the Safavid Shah ‘Abbas I (1571– 1629) 1 actively encouraged foreign travel to Iran, and created a hospitable situation for trade and diplomatic exchange. Europeans from a number of Catholic and Protestant 1 On this important Safavid ruler, see David Blow, Shah Abbas: The Ruthless King Who Became an Iranian Legend (London: I. B. Tauris, 2009); and Sheila R. Canby, Shah ‘Abbas: The Remaking of Iran (London: British Museum Press, 2009). For historical background on the Safavids see Andrew Newman, Safavid Iran: Rebirth of an Empire (London: I. B. Tauris, 2006). 130 eLio BrAnCAforte 130 lands were attracted by “his outward looking agenda […] centered on a new resplendent capital, Isfahan. This coincided with and was partly responsible for, an active European interest in Iran as a land of religious, commercial, and strategic opportunity.” 2 Some came as missionaries hoping to establish residency in Isfahan; many others came as merchants wishing to take advantage of the silk or jewel trade; still others arrived as ambassadors trying to convince the Safavids to attack the Ottomans. There were also curious travellers who wanted to learn more about Persia on their way further east. What all those European travellers had in common was their interest in describing the land, its peoples, customs, history, along with details of the flora and fauna. 3 These early modern voyagers, most of whom arrived from areas of religious strife, and had witnessed numerous wars on the European continent during the sixteenth and seventeenth cen-turies, saw the split between Sunnis and Shi‘ites as paralleling the Protestant/Catholic divide. - eBook - PDF

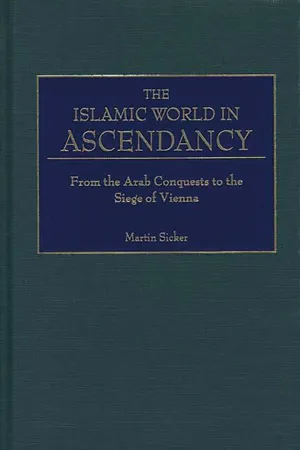

The Islamic World in Ascendancy

From the Arab Conquests to the Siege of Vienna

- Martin Sicker(Author)

- 2000(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

In effect, the Ottoman Empire was being subjected to a virtual and intolerable economic blockade. In addition, Safavid religious militancy generated pressures on Suleiman, in his role as preeminent leader of the orthodox Sunnite Muslim Page 205 world, to take action against the spread of Shiite beliefs and practices, which were widely considered to be heretical. Safavid military activism along the Ottoman frontier also resulted in the defection of the khan of Bitlis, south of Lake Van, and the defeat of the Ottoman troops who had attempted to seize the town. To make matters worse, the governor of Baghdad, who had just recently pledged his allegiance to Suleiman, had been murdered and the city was returned to Safavid control. Ibrahim Pasha, the Ottoman grand vizier, had been advocating a campaign against Persia for years but could not convince Suleiman to take action while the Safavid Empire was still in a state of disarray as a result of the civil conflict that erupted over the succession to the Persian throne. After the last two incidents, however, Suleiman became determined to march against the Safavids. Within three months after the 1533 peace agreement with the Hapsburgs, advance elements of Suleiman’s army, under the command of Ibrahim Pasha, were on the march in Asia. Coincidentally, the year 1533 also marked the end of the civil war in Persia and the reassertion of royal authority by Tahmasp, who ended a decade of rule by his qizilbash regents and advisers. During that time, Persia had been challenged in the east repeatedly by the Uzbeks, who invaded Khorasan from Central Asia five times in the preceding ten years. Now, with the country unified under Tahmasp’s centralized control for the first time in a decade, the shah marched into Herat in the fall of 1533 in preparation for an invasion of Transoxiana, where he hoped to complete the decisive defeat of the Uzbeks. - eBook - PDF

Notables, Merchants, and Shaykhs of Southern Iran and Its Ports

Politics and Trade in the Persian Gulf, AD 1729-1789

- Thomas M. Ricks(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Gorgias Press(Publisher)

There were also areas of strong pro-Safavid sentiment. Thus, any attempts on the part of Nader to centralize his political authority in order to ensure greater economic gains exacerbated the already existing anti-Afsharid and pro-Safavid sentiments of the two regions. 140 The existence and importance of these social, and cultural loyalties were based primarily on past economic and political favors received by the Safavids (that is, from Shah Abbas I) and close religious and social ties with the old ruling family. The remaining portions of this discussion will examine the region of Southern Iran, that region’s social, political, and economic relationship with the Gulf port-towns and its peoples from AD 1700 to 1745. 140 Kasravi, Khuzistan , pp. 52–3. The western portion of present-day Khuzistan was known in the early 16th century as “Arabistan” and encompassed the Mosha’sha’ lands, that is, lands west of the Karun river. The eastern portion—Dizful, Shushtar, and Ramhurmuz—were part of Kuhgilu at times and part of “Arabistan” at others following the structure of the valiship and beglarbegi-ship of the old Safavid provinces (Kasravi, Khuzistan , p. 53, fns. 1 and 2 and Lockhart, Safavi Dynasty , p. 5, fn, 3). P OLITICAL AND S OCIOECONOMIC S TRUCTURES 49 Table 2. 22 Principal Offices in the Central and Southern Administration of Iran, 1700–1750: Their Numbers and Presence under the Ruling Families Offices: Late-Safavid a Afghan b Afshar c Vali of Georgia 1 1 1 Vali of Kurdistan 1 1 1 Vali of Ardalan 1 1 1 Vali of Luristan 1 1 1 Vali of Khorasan 0 0 1 Beglarbegis 14 14 16 Soltan — 109 — Sardars 10 8 14 I’timad al-Dawleh 1 1 1 Vakil al-Dawleh 0 0 1 Qurchibashi 1 1 1 Qollarbashi 1 1 1 Ishikaqasibashi 1 1 1 Tofangchibashi 1 1 1 Tupchibashi 1 1 1 Nazir-e Buyutat 1 1 1 Divanbegi 1 1 1 Majlisnevis 1 1 1 Munshi al-Mamalik 1 1 1 Sadr-e Khasseh 1 1 1 Daryabegi 0 0 1 Sources: a Tuhfeh-e Shahi ; b Tadhkirat al-Muluk ; c Lockhart, Nadir Shah . - eBook - PDF

The World Imagined

Collective Beliefs and Political Order in the Sinocentric, Islamic and Southeast Asian International Societies

- Hendrik Spruyt(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

For example, when a Shi’a caravan was attacked by an Ottoman garrison, the Safavid governor and owner of the caravan 63 De le Garza suggests that practices that were acceptable to Chinggis Khan or Timur had become less so with their descendant Timurids, the Mughal Empire. Garza 2010, 261–71. 64 Çelik 2011, 19. 65 Dressler 2005, 151. The Qizilbash were among the most militant Shi’a and formed part of the shock troop contingents in the Safavid army. 66 Tucker 1996, 19. Collective Imagination and the Conduct of Interpolity Relations 231 complained to the Ottoman governor of Erzurum, the intended destination of the caravan. The Ottoman governor thereupon prosecuted and executed the perpetrators. 67 Indeed, even in the sixteenth century, trade routes expanded between Persian and western Anatolia despite the wars. 68 Likewise, there is little evidence that the Ottoman blockade of the Safavid Empire (1603–18) was enforced. Interestingly, given the vituperative nature of Ottoman diatribes, “The Safavid chronicles treated the Ottomans with much greater respect and virtually never raised religious issues, preferring to portray the Ottomans as worthy adversaries in battle, but more importantly, as victorious war- riors of Islam against the Europeans.” 69 The Safavids at least recognized a common Islamic identity with the Ottomans. Perhaps most remarkable were the continued friendly interactions. “Interdynastic relations between the Ottomans and Safavids were char- acterized by numerous congratulatory letters, embassies, and gift exchanges, particularly upon the enthronement of new monarchs.” 70 Despite the sectarian schism, the shared adherence to the five pillars of Islam also made rapprochement between the two parties possible. 71 Given that Shi’i adhered to these as did the Sunni, Ottoman legal scholars found grounds to object to the fatwa against the Persians.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.