History

The Gutenberg Printing Press

The Gutenberg Printing Press, invented by Johannes Gutenberg in the 15th century, revolutionized the production of books by introducing movable type. This innovation made it possible to produce books more quickly and at a lower cost, leading to a significant increase in the availability of printed materials and the spread of knowledge and ideas.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "The Gutenberg Printing Press"

- eBook - PDF

Rewriting Nature

The Future of Genome Editing and How to Bridge the Gap Between Law and Science

- Paul Enríquez(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

5 The amalgam of knowledge, curiosity, creativity, and action aimed at speeding up the printing process, which culminated in the ingenious design of the first movable- type printing press, fundamentally transformed the world. By the end of the fifteenth century, Gutenberg’s invention had spread all over Europe. For the first time in history, books could be produced en masse and at a low cost relative to other printing methods. Indeed, more than twenty million books had been printed by the year 1500. 6 1 The printing press ushered in a new revolution in mass communication and dissemination of information that contributed to the rise of public literacy and the end of the Dark Ages. Although The Gutenberg Printing Press did not jumpstart the Renaissance, it undoubtedly fueled its swift progression. Nicolaus Copernicus, the revered Renaissance mathematician and astronomer, as well as other scientists and scholars of the time benefited directly from the printing press. Copernicus, for instance, profited greatly from the printing of various astro- nomical tables that began to appear in the late fifteenth century—including the Alfonsine Tables, which date back to the year 1252. 7 Astronomical tables contained data to calculate ecliptic longitudes—as well as the position of celestial bodies, including the Sun, Moon, and other planets—that were useful in maritime naviga- tion during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries when Spain, Portugal, England, France, and other wealthy nations ventured out to sea in search of new lands. Copernicus built upon data from these tables in his groundbreaking book De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres), which set off the scientific revolution. 8 The book conceptualized his elegant and controversial theory of heliocentricism, which postulated that the Sun—not the Earth—was at the center of the Universe, and that Earth and other known planets actually revolved around the Sun. - eBook - PDF

Icons of Invention

The Makers of the Modern World from Gutenberg to Gates [2 volumes]

- John W. Klooster(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

After about 1475, the number of new handwritten books declined. Printing promoted the dissemination of information and the development of libraries, paper, and education, and particularly reading capacity and lit- eracy (whereas previously, few people were trained to read). Printing and cheap books made literacy worthwhile. Scholarship broadened, and the numbers of the educated grew. Dissemination of information quickened. Scholars became a group and were no longer isolated individuals. Martin Luther’s rebellion against the Church may have succeeded, in contrast to earlier rebellions, because Luther could use the press to broadcast his posi- tion. Although a century was to pass before the Scientific Revolution, print- ing probably made the revolution inevitable. Fifteenth- and even many sixteenth- century printers and publishers mainly produced known works on theology, law, and medicine. Many of the best-selling authors, such as Cicero, St. Thomas Aquinas, and St. Augus- tine, had been dead for centuries. However, wide publication of current events and achievements also occurred, such as when Columbus returned from the New World in 1493, and his report to the Spanish emperors was rapidly translated into Latin and published in three Rome editions. 12 Icons of Invention Subsequent improvements in paper making and press technology, such as rolled starting paper and continuous feed, allowed printing at higher speeds and lower cost. However, centuries passed before the need to set by hand lines and pages of Gutenberg’s cast type was changed by further developments. The famous early English printer, William Caxton, learned the trade of printing based on Gutenberg technology in Europe and established his press in Westminster, England, in 1476. Consistent with the Gutenberg idea of printing type, which was calligraphic and resembled handwriting, Caxton developed the Black Letter type that resembled the writing of the monks of Haarlem, Holland. - eBook - ePub

Learning Technology

A Complete Guide for Learning Professionals

- Donald Clark(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Kogan Page(Publisher)

The core technology in the 15th century was moveable type. The compositor set each letter, in reverse, on sticks, bedded it down and adjusted as necessary, with each page being separately printed. This was not easy, and just like manuscript writing, errors were easy to make. The initial investment needed was quite high and if sales were better than expected the whole process had to be repeated in order to produce more copies. Paper remained a problem even after the printing press was developed, as it was so expensive. Gutenberg got into deep debt and had to pass his workshop over to his investor. One of his first books, the Gutenberg Bible, took two years to typeset and print.What the printing press did was scale production and distribution. The number of books available increased significantly, prices plummeted and the idea of writing new works to be printed, as opposed to just reading fixed texts, took hold. It was a technology (or set of technologies) that was to cause irreversible change in the world.The Bible was, of course, the first book to be printed, along with indulgences by the Catholic Church, the misuse of which led to Luther’s Protestant Reformation and his best-selling, vernacular German Bible (200,000 in his lifetime). The boost to science was also considerable, as findings, criticism and commentaries could be written, printed and disseminated at speed.Scalability of knowledge

Printing technology allowed knowledge to be made, distributed and stored more easily and on scale. It was not a process of replacement, as printing extended the reading of classical and medieval texts. Neither was it wholly secular or humanist.Just as importantly, previously preserved written texts could now be printed, saving original texts from the possibility of destruction and damage. Most of the works by the pre-Socratic philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle, and most of the output from Greek dramatists, had been lost. Printing preserved what we have, its scale preventing the losses inherent in scarce written texts.Printing also brought a degree of standardization of written language. Interestingly, some printers added letters to pad out lines to the right-hand margin, such as an extra ‘e’ on the end of words. In its own way, printing also selected and to a degree determined and controlled literature and knowledge. Technology, once again, became the underlying driver behind cultural expansion. - eBook - PDF

- George Parker Winship(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

These distinctions have at times been claimed for the Bible, by thoughtless popular-izes, who not infrequently have also claimed, and quite justifiably, that this monumental piece of printing exhibits a mastery of typographical technique which left nothing of essential, basic importance that had to be changed subse-quently. The invention of printing, or more accurately of typog-raphy, meant the substitution of individual metal letters that could be used over and over again, in the place of sepa-rate letters put on paper with a pen and ink once for all. Even more fundamentally, printing meant the production of reading matter, chiefly books, in quantity by mechanical means instead of by hand one at a time. Some means of producing a quantity output had to be devised, because the ordinary routine of life all over Europe had been com-pletely reorganized between the thirteenth and the begin-ning of the fifteenth centuries. Overlooking superficial dif-ferences and considering their underlying causes, European life in the fourteenth century, when these changes were coming about, was basically similar to what it was in the [2] GUTENBERG'S INVENTION nineteenth century. Modern innovations in transportation have altered all the externals of everyday existence, but none of the consequences that have followed the building of railroads, the internal combustion of gasoline, or sky-scraping transports, affected food supplies or international communications more completely or more permanently than did the widening of bridle trails by ox-drawn wains which beat down ruts into roads on which horses could pull lighter vehicles at a trot. The village markets were supplied from more distant farms; the local craftsmen could buy food more advantageously than they could raise it in their own kitchen gardens; middlemen intro-duced the germs of the factory system to supply more distant markets that would pay higher prices. - Euan Cameron(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

In consequence the Bible would come, in the 150 years after the invention of print, to occupy a special place both in the transformation of the European book world and in the cultural history of its peoples. It became a prime 1 Paul Needham, ‘The Changing Shape of the Vulgate Bible in Fifteenth-Century Printing Shops’, in Paul Saenger and Kimberley van Kampen (eds.), The Bible as Book: The First Printed Editions (London: British Library, 1999), pp. 53–70. Andrew Pettegree 160 motivator in change in the geography of the book industry, yet for workers in the industry it also encapsulated the pitfalls that lay in wait for those who ventured too far, in a business where fortunes were as easily lost as won. It is possible that Gutenberg’s experiments with printing may have begun some years before his arrival in Mainz in 1444. 2 During the previous five years in Strasbourg he had entered into a number of business associations. Documents relating to the legal cases that subsequently arose made several mysterious references to presses and metalworking techniques. Whatever this may indicate Gutenberg certainly came to Mainz with considerable expertise both in metalworking (he was a trained goldsmith) and of raising capital through the sort of joint undertaking that had financed his imagina- tive scheme selling printer’s mirrors for the Aachen pilgrimage of 1440. Both these skills would stand him in good stead for the painful years of discovery that lay ahead. The invention of printing should more properly be considered the bring- ing together of several different new discoveries, together with the modified application of a number of working practices already familiar from medieval craft society. The critical core was the invention of the mould for hand casting of individual pieces of type. This was a complex wooden frame, into which a soft metal alloy could be poured, and from which set type could then be released.- eBook - ePub

Public Parts

How Sharing in the Digital Age Improves the Way We Work and Live

- Jeff Jarvis(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Simon & Schuster(Publisher)

Though she ended up disagreeing with McLuhan’s views about technological inevitability, he convinced her of Gutenberg’s impact. Eisenstein chronicles the impact of movable type mostly in Europe, not its earlier introduction in the Far East, where the press did not—as we would say today—go viral. John Man, in his entertaining biography, The Gutenberg Revolution, provides a survey of earlier art. Reproducing a font’s characters ad infinitum is “an idea so obvious that it occurred to human beings remarkably early.” 4 The Phaistos Disc, made about 1700 B.C., has 241 images impressed onto its clay with metal stamps (they remain undeciphered). Ancient Egyptians used wooden blocks to set hieroglyphics onto tile. A key ingredient in printing—paper—was invented in China by A.D. 105 (or two hundred years earlier, according to some accounts 5) and brought to Korea and Japan five centuries later. The idea of impressing images on paper with stamps seems to have been born in the fifth century, Man reports. In the eighth century, books were being printed from blocks of wood or stone in China, Japan, and Korea. In 1234, Korea took the lead with the first use of movable type. But the writing systems of all three languages were too complex; calligraphy was still more efficient than printing. With the Latin alphabet and Gutenberg’s innovations, printing at last became sustainable and scalable. “One year,” says Man, “it took a month or two to produce a single copy of a book; the next, you could have 500 copies a week.” 6 This revolution wasn’t just cultural, it was economic. In the early modern period, Paul Yachnin’s Making Publics project says, culture found customers and a market to support itself, replacing the resources and control of the church and powerful patrons - eBook - PDF

Advanced Typography

From Knowledge to Mastery

- Richard Hunt(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Visual Arts(Publisher)

Example of the humanist manuscript style of the 1400s that was the basis of Roman type. & molte genti CHANGING TECHNOLOGIES AND PRACTICE 17 of labour. The first printing presses were an early iteration of the assembly line that became the basis of efficient manufacture of automobiles and other mass-produced products. In a sense, the printing press was the industrial robot of its day, replacing human labour with technology. The development of the printing press in Europe anticipated production processes in other fields. The production of printed matter with a press became a model for the division of labour of mass production in the Industrial Revolution, something that has culminated in today’s industrial methods. While the work of the scribe became unnecessary, more and more printers and other craftspeople associated with printing were needed. By 1500, less than fifty years after Gutenberg’s Bible, there were printing presses in over 250 cities across Europe, with more than 20 million books estimated as having been printed. The in- creased availability of reading material encouraged more people to learn to read, which in turn led to an even greater demand for print. Some of the information contained in these books led to develop- ments in science and technology. Previously, most learning had to be started from scratch by each person in each field, because pre- vious knowledge developed by others elsewhere was inaccessible. - Paul M. Dover(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

This was evident early on in Italy, with its commitment to written government, its thriving epistolary culture, and its 20 Michael Giesecke, Der Buchdruck in der frühen Neuzeit. Eine historische Fallstudie über die Durchsetzung neuer Informations- und Kommunikationstechnologien (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1991), 145. 21 Flood, “The printed book as a commercial commodity,” 173. 22 Andrew Pettegree, The Book in the Renaissance (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), 42. 23 Wolfgang Schmitt, “Die Ianua (Donatus): Ein Beitrag zur lateinischen Schulgrammatik des Mittelalters und der Renaissance.” Beiträge zur Inkunablekunde, dritte Folge, 4 (1969), 43–80. 24 John Man, The Gutenberg Revolution. How Printing Changed the Course of History (New York: Random House, 2010), 155–156. Revolutionary Print 157 large ecclesiastical footprint. The best estimates are that between 36 and 44 percent of all incunabula were of Italian origin. 25 These numbers do not include the copious editions of placards, posters, pamphlets and indulgence certificates that have disappeared without a trace. Venice, in particular, soon emerged as a major printing hub, such that, by 1471, one-third of all the printed books produced in Europe emanated from Venice. 26 By the sixteenth century, more than 100 Italian towns had printing presses. In the last two decades of the fifteenth century, the printing press became a commonplace in towns across northern Italy, the Rhineland, and Low Countries. By the early sixteenth century, all the major cities of Western Europe had printing presses, with Venice, Paris, and Lyons as the leading centers. In the decades that followed, German printing underwent rapid expansion. The British Library’s Short title catalogue of Books printed in Germany up to 1600 shows 150 distinct German and Austrian towns with publishing or printing activities.- eBook - ePub

A History of Mechanical Inventions

Revised Edition

- Abbott Payson Usher(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Dover Publications(Publisher)

CHAPTER XThe Invention of Printing

I

The development of printing, more than any other single achievement, marks the line of division between medieval and modern technology. In form and in substance, it was indicative of an epoch-making technical change. In this achievement we have the first instance of a process being pushed through to a decisive stage in a relatively short time, notwithstanding the remoteness of the ends to be achieved. Despite the obscurity of the records, it seems evident that the final result involved more imaginative effort and less of mere empiricism than had commonly been the case with inventions. We see here the same transfer to the field of the imagination that is clearly evident in all the work of Leonardo da Vinci. The process of accomplishment is evidently different from that involved in the development of the mechanical clock. The consequences of the achievement, too, were of commanding importance. The possibility of producing books at lower cost and of higher standards of accuracy contributed decisively to the diffusion of scientific and technical knowledge, thus intensifying the effect of the new intellectual activities and contributing an essential feature to the development of modern scholarship, with its growing emphasis on written, as distinct from oral, communication and instruction. If we include in this general development, as we should, the related arts of engraving and etching, we must note the significance to cartography of the new methods of reproduction as finally perfected by the Antwerp school of the sixteenth century—a scientific accomplishment of the utmost moment to the development of commerce.But even apart from these less direct technical consequences, the new processes are significant in themselves. Printing is one of the first instances of the substitution of mechanical devices for direct hand work in the interests of accuracy and refinement in execution as well as reduced cost. By capitalistic methods and mass production, a new and superior product was evolved. All the economic consequences of these inventions were thus characteristic of the new order; and even at the outset, the printing office disclosed the features of a factory enterprise rather than those of the craft shop. - eBook - ePub

The Republic of Games

Textual Culture between Old Books and New Media

- Elyse Graham(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- McGill-Queen's University Press(Publisher)

The narrative begins with printing (c. AD 1450) rather than with the alphabet (c. 2000 BC), with writing (c. 5000 BC), or with speech, but despite the importance often attributed to Johann Gutenberg (c. 1400–68), whom readers of one British newspaper voted ‘man of the millennium’ (Sunday Times, 28 November 1999), there is no clean break or zero point at which the story begins, and it will sometimes be necessary to refer briefly back to the ancient and medieval worlds.” 33 Yet the most visible parts of the book telescope our attention to those zero points of the press and the Internet: not only the title, but also the image on the cover, which places together, in a pas de deux, the letter “i” (a common symbol of Internet culture) and a printing press. This sort of motif is common. The cover illustration of From Gutenberg to Zuckerberg is a printing press that is visibly emitting a Wi-Fi signal. Trade books, which sell solutions as much as they do analysis, may have a special incentive to claim that changes in media technologies create changes in human consciousness. Nicholas Carr’s bestseller The Shallows opens with the claim that “For the last five centuries, ever since Gutenberg’s printing press made book reading a popular pursuit, the linear, literary mind has been at the centre of art, science, and society.” 34 But although critics such as Briggs and Burke have moved away from models like Carr’s, which echoes McLuhan and Ong in its longing look back at a vanishing or vanished mentality, the framing elements in their works often tacitly endorse these models. In this sense, the marketplace exerts a strong enough force that scholars can find themselves making implicit claims in favour of views of media culture and media change that they question or even explicitly oppose - eBook - PDF

The Law Emprynted and Englysshed

The Printing Press as an Agent of Change in Law and Legal Culture 1475-1642

- David John Harvey(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Hart Publishing(Publisher)

13 Although some readers copied a printed text by hand, a throwback to the only way a text could circulate in pre-print 9 Ibid, at 362. 10 For historians the term ‘Early Modern period’ is a generalisation for a roughly 300-year his-torical period covering the late 15th to early 18th centuries. 11 Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change , above n 1, at 159. 12 Thomas Jefferson observed that because a larger number of books were printed than were available in manuscript, the chances of more copies surviving were greater: Thomas Jefferson to Ebenezer Hazard, 18 February 1791, in MD Peterson (ed), Thomas Jefferson: Writings (Library of America, New York, 1984), at 973. Jefferson also expounded on the preservative power of print in a letter to George Wythe dated 16 January 1796, stating, of his researches into the laws of Virginia, ‘our experience has proved to us that a single copy, or a few, deposited in MS in the public offices cannot be relied on for any great length of time’ (ibid, at 1031). 13 See Professor John Baker’s discovery of the notebooks of Sir John Port: JH Baker (ed), The Notebook of Sir John Port (Selden Society, London, 1986). Eisenstein’s Theory 5 days, it was quicker for the reader or scholar to buy the book, even if that meant sending an order and waiting for it to be delivered. Upon receipt, access to the text was immediate, and there was no need to copy it and return the exemplar to the owner. In this way printed texts circulated in larger quantities to a more widely dispersed audience. 14 Eisenstein identifies six features or qualities of print that significantly differ-entiated the new technology from scribal texts: a) dissemination; b) standardisation; c) reorganisation; d) data collection; e) fixity and preservation; and f) amplification and reinforcement. 15 Some of these features had an impact, to a greater or lesser degree, upon com-munication structures within the law. - eBook - PDF

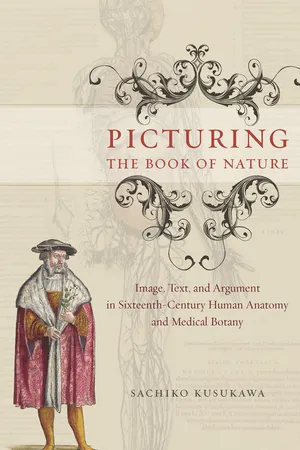

Picturing the Book of Nature

Image, Text, and Argument in Sixteenth-Century Human Anatomy and Medical Botany

- Sachiko Kusukawa(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- University of Chicago Press(Publisher)

part 1 ; printing pictures ' By the sixteenth century, most university-educated physicians be-lieved in the importance of the printed book: it was the primary medium by which they learned about their subject and the opin-ions of the ancients, and it was also the means by which they ex-pressed their views about their subject and commented on classical authors. A few physicians came to insist that their books had to have pictures in them. Although by then a printed book containing pictures was not uncommon, such a book, like any artifact, did not come into existence out of thin air. Not only did the author’s labor, hope, and expectation go into its production, but there were also publishers, artists, and engravers whose skills, support, and coop-eration were indispensable. 1 Thus, this part deals with the technical (chapter 1) and financial (chapter 2) aspects of book production, the practices of copying and coloring they gave rise to (chapter 3), and the means of control sought by publishers and authors in protecting the fruits of their labor (chapter 4). These were the con-ditions of the book’s material production that authors, including Fuchs and Vesalius, who wanted to develop specific connections between their texts and their images had to manage and negotiate. chapter 1 Techniques and Craftsmen By the time Johannes Gutenberg printed the Bible using movable type, two means of replicating images were known: woodcuts and incised metal plates. 2 The new art of mechanically replicating texts soon incorporated both, with varying degrees of success. Woodblocks The technique of printing patterns on cloth using woodblocks, famously described in Cennino Cennini’s (c. 1370–1440) Il libro dell’arte ( Book of Art ), appears to date from the fourteenth cen-tury. 3 Woodblocks were used to print devotional images on pa-per from the early fifteenth century (fig. 1.1). 4 Some manuscript books had such woodcuts pasted in, or carried decorative initials stamped with woodblocks.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.