What is Cyberfeminism?

PhD, English Literature (Lancaster University)

Date Published: 17.10.2023,

Last Updated: 31.01.2024

Share this article

Definition and origins

Cyberfeminism grew out of third-wave feminism in the 1990s and explores the relationship between gender, digital technology, and the internet. As Mia Consalvo writes,

Cyberfeminists explore many areas of theory: that women are naturally suited to using the Internet, as both share important commonalities; that women can best empower themselves by becoming fluent in online communication and acquiring technological expertise; and that women would do best to study how power and knowledge are constructed in technological systems, and how and where feminists can disrupt and change these practices for the betterment of all members of society. (“Cyberfeminism,” in Encyclopedia of New Media, 2002)

Edited by Steve Jones

Cyberfeminists explore many areas of theory: that women are naturally suited to using the Internet, as both share important commonalities; that women can best empower themselves by becoming fluent in online communication and acquiring technological expertise; and that women would do best to study how power and knowledge are constructed in technological systems, and how and where feminists can disrupt and change these practices for the betterment of all members of society. (“Cyberfeminism,” in Encyclopedia of New Media, 2002)

The term “cyberfeminism” was coined independently and simultaneously by feminist Sadie Plant and the artistic group VNS Matrix. In Plant’s 1996 essay “On the Matrix: Cyberfeminist Simulations,” she defines cyberfeminism as

an insurrection on the part of the goods and materials of the patriarchal world, a dispersed, distributed emergence composed of links between women, women and computers, computers and communication links, connections and connectionist nets.

[...]

It is a comment which indicates the utopianism which lies at the heart of cyberfeminism, which argues that technology is not inimical to women, and that women should seize control of new information systems. (Excerpted in The Gendered Cyborg, 2013)

Edited by Fiona Hovenden, Linda Janes, Gill Kirkup, and Kathryn Woodward

an insurrection on the part of the goods and materials of the patriarchal world, a dispersed, distributed emergence composed of links between women, women and computers, computers and communication links, connections and connectionist nets.

[...]

It is a comment which indicates the utopianism which lies at the heart of cyberfeminism, which argues that technology is not inimical to women, and that women should seize control of new information systems. (Excerpted in The Gendered Cyborg, 2013)

The view of cyberspace as an empowering utopia for women has been the subject of much debate within cyberfeminism, which we will return to later in this guide.

Plant further argues that the internet is a crucial space for dismantling patriarchal power structures:

Complex systems and virtual worlds are not only important because they open spaces for existing women within an already existing culture, but also because of the extent to which they undermine both the world-view and the material reality of two thousand years of patriarchal control. (1996, [2013])

This view that cyberspace is used to bring about a sexual revolution and disrupt patriarchal structures is further elaborated upon in Plant’s book Zeroes + Ones (1997).

Other feminists have outlined a comprehensive definition of cyberfeminism. In “From Cybernation to Feminization: Firestone and Cyberfeminism,” Susanna Paasonen writes that, as with the definition of “cybernetic,” the definition of “cyberfeminism” is also “broad and diverse” (in Further Adventures of The Dialectic of Sex, 2010). Paasonen describes the relationship between cyber and feminism in three ways:

- Cyberfeminism is the “feminist analyses of human-machine relations, embodiment, gender, and agency in a culture saturated with technology.”

- Cyberfeminism is “a critical position that interrogates and intervenes in technology.”

- Cyberfeminism is the “analyses of the gendered user cultures of information and communication technologies (ICT) and digital media, their feminist uses, as well as the social hierarchies and divisions involved in their production and ubiquitous presence.”

(2010)

In 1997, the Old Boy’s Network, founded by German artist Cornelia Sollfrank, launched the first Cyberfeminist International Conference, followed by the publication First Cyberfeminist International (1998). The conferences, and subsequent publications, comprised various lectures and artworks.

This guide will explore the relationship between cyber and feminism, from how the figure of the cyborg (part machine, part organic) and the act of disembodiment in online spaces can challenge gender roles, to reproductive technologies. These issues at the forefront of cyberfeminism will be highlighted through manifestoes, academic scholarship, and artwork.

The Cyborg Manifesto (1985)

Donna Haraway’s manifesto, in many ways, provided the foundations for cyberfeminism. Haraway is a prominent scholar of ecofeminism and posthumanism. “The Cyborg Manifesto” (reprinted in Simians, Cyborgs, and Women, 2013) discusses how the cyborg, a fusion of organism and machine, allows us to reassess our assumptions about what it means to be human.

A cyborg is typically seen as an organism with an augmented reality that has circular processing and is part of a collective. Haraway extends this definition, viewing the cyborg as a creature partly formed through lived experience, developed through the ways we communicate with one another. The cyborg, for Haraway, is “a kind of disassembled and reassembled, postmodern collective and personal self” (1985, [2013]). This is the self, Haraway argues, feminists must “code”(1985, [2013]).

According to Haraway, the cyborg can help develop a new understanding of the self for feminists because:

- The cyborg challenges essentialist concepts of gender.

- The cyborg challenges traditional concepts of identity.

To address this first point: cyborgs are not tethered to a biological concept of what it means to be human. This aligns with many feminists’ rejections of gender essentialism, i.e., the idea that women cannot all be tied together through a biological understanding. Haraway writes,

The cyborg is a creature in a post-gender world; it has no truck with bisexuality, pre-oedipal symbiosis, unalienated labour, or other seductions to organic wholeness through a final appropriation of all the powers of the parts into a higher unity. (1985, [2013])

Donna J. Haraway

The cyborg is a creature in a post-gender world; it has no truck with bisexuality, pre-oedipal symbiosis, unalienated labour, or other seductions to organic wholeness through a final appropriation of all the powers of the parts into a higher unity. (1985, [2013])

Cyborgs can also replicate without the need to produce, rejecting the patriarchal figure of the father and challenging our understanding of the family and the biologically determined “role” of women.

The cyborg’s disruption of identity can be seen in the way online spaces allow us to create avatars, forging new identities for ourselves in cyberspace. The potential impact of disembodiment online to promote gender equality has been a source of contestation.

VNS Matrix

VNS Matrix, a cyberfeminist art movement in Australia from 1991 to 1997, was largely inspired by Haraway’s manifesto. The group consisted of members Josephine Starrs, Julianne Pierce, Francesca da Rimini, and Virginia Barratt and their most well-known work was a billboard displaying their manifesto “A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century.” Here, they claim

we are the virus of the new world disorder

rupturing the symbolic from within

saboteurs of the big daddy mainframe

the clitoris is a direct line to the matrix

the VNS MATRIX

(VNS Matrix, 1991)

The text linked the female body to emerging technologies, subverting the idea that technoculture is inherently masculine. The Matrix’s aim to sabotage “big daddy mainframe” via a virus suggests that cyberfeminists and female hackers were using the tools of the patriarchy to reclaim a new online space for women.

The group wrote a second manifesto in 1996, before they disbanded entitled “Bitch Mutant Manifesto.” This later manifesto stated:

The net's the parthenogenetic bitch-mutant feral child of big daddy mainframe. She's out of of [sic] control, kevin, she's the sociopathic emergent system. (VNS Matrix, in 50 Feminist Art Manifestos, 2022)

Edited by Katy Deepwell

The net's the parthenogenetic bitch-mutant feral child of big daddy mainframe. She's out of of [sic] control, kevin, she's the sociopathic emergent system. (VNS Matrix, in 50 Feminist Art Manifestos, 2022)

VNS Matrix argues that this capitalist, patriarchal space has created something which has spun far beyond its control. This is further emphasized by Plant, who writes:

Like woman, software systems are used as man’s tools, his media and his weapons; all are developed in the interests of man, but all are poised to betray him. (Plant, “The Future Looms,” in Cyberspace/Cyberbodies/Cyberpunk, 1996)

Edited by Mike Featherstone and Roger Burrows

Like woman, software systems are used as man’s tools, his media and his weapons; all are developed in the interests of man, but all are poised to betray him. (Plant, “The Future Looms,” in Cyberspace/Cyberbodies/Cyberpunk, 1996)

Both Haraway and VNS Matrix create the image of cyberspace as a place where gender roles are subverted and where masculine dominance becomes threatened.

Disembodiment and identity in cyberspace

Are women truly cyborgs online: genderless and untethered to patriarchal structures and biological roles? Following Haraway’s manifesto, many cyberfeminists became interested in the extent to which women are disembodied online and how much freedom and autonomy this grants.

This ability to morph into different identities online offered, for Legacy Russell, a type of liberation:

I found new landscapes through being borne and carried online, those early days where I flexed as a digital Orlando, shapeshifting, time-traveling, genderfucking as I saw fit. I became myself, I found my body, through becoming, embodying, a glitch. (2020)

Legacy Russell

I found new landscapes through being borne and carried online, those early days where I flexed as a digital Orlando, shapeshifting, time-traveling, genderfucking as I saw fit. I became myself, I found my body, through becoming, embodying, a glitch. (2020)

This adoption of different characteristics is known as “identity tourism,” and it has been a subject of much debate among cyberfeminist scholars.

Identity tourism, a term coined by Lisa Nakamura in Cybertypes, describes “the process by which members of one group try on for size the descriptors generally applied to persons of another race or gender” (2013). Claims that cyberspace and emerging technologies can strip away these identity markers are problematic for a number of reasons. As Jessie Daniels argues in “Rethinking Cyberfeminism(s),”

The fact that race matters online, as it does offline, counters the oft-repeated assertion that cyberspace is a disembodied realm where gendered and racialized bodies can be left behind. (In Women, Science, and Technology, 2013)

Edited by Mary Wyer et al.

The fact that race matters online, as it does offline, counters the oft-repeated assertion that cyberspace is a disembodied realm where gendered and racialized bodies can be left behind. (In Women, Science, and Technology, 2013)

Daniels explores instead how embodiment on the internet, rather than disembodied identity tourism, renders cyberspace a site of resistance and affirmation for marginalized groups. Daniels argues,

For some, the Internet economy reproduces oppressive workplace hierarchies that are rooted in a global political economy. For others, the Internet represents a “tool” for global feminist organizing and an opportunity to be protagonists in their own revolution. For still others, the Internet offers a “safe space” and a way to not just survive, but also resist, repressive sex/ gender regimes. (2013)

Among other examples, Daniels points to forums and sites which provide medical information to transgender women. When such spaces on the internet are accessed, they “enable [women] to transform their embodied selves, not escape embodiment” (2013). Moreover, sites which offer support to those from LGBTQ+ groups and other marginalized communities can allow individuals to reaffirm their identities online.

Reproductive technologies

Cyberfeminism is not solely concerned with women’s activities online, but also in how digital technology more broadly impacts upon gender equality. A major issue within cyberfeminism, and feminism more broadly, are reproductive technologies, such as ultrasounds and artificial reproduction.

Please note, I will be referring to “women” within this discussion of reproduction due to the literature referenced, though I fully acknowledge that not all pregnant people identify as women. The lack of inclusivity in this discourse has been raised by some scholars and has resulted in the creation of xenofeminism, an offshoot of cyberfeminism which is more inclusive of the trans and queer community.

The gender equalizing potential of reproductive technologies has previously been discussed by radical feminist Shulamith Firestone. In The Dialectic of Sex (1970), Firestone explains how, traditionally, reproduction has a huge physical, mental, and emotional cost for women. She writes,

the biological family unit has always oppressed women and children, but now, for the first time in history, technology has created real preconditions for overthrowing these oppressive ‘natural’ conditions, along with their cultural reinforcements. (1970, [2015])

Shulamith Firestone

the biological family unit has always oppressed women and children, but now, for the first time in history, technology has created real preconditions for overthrowing these oppressive ‘natural’ conditions, along with their cultural reinforcements. (1970, [2015])

Firestone advocates for artificial reproduction as a way of both sparing women the difficulty of labor, as well as freeing them from dependency on their male partner. Firestone argues that, as artificial insemination and artificial ovulation are already a reality, parthenogenesis (a virgin birth) could be developed soon, something which Firestone argues we are not culturally ready for:

It is clear by now that research in the area of reproduction is itself being impeded by cultural lag and sexual bias. The money allocated for specific kinds of research, the kinds of research done are only incidentally in the interests of women when at all. (1970, [2015])

Artificial reproduction, for Firestone, allows for the reassessment of motherhood as the only viable option for women.

The question of what role technology will play in reproduction and the liberation of, or further oppression of, women continues today. As Haraway argues in “The Virtual Speculum in the New World Order,” technology such as video cameras, microcinematography, and sonography machines render the fetus a “public object” (in The Gendered Cyborg, 2013). The highly visible and public nature of reproductive technologies, Haraway argues, poses significant implications for a woman’s choice regarding pregnancy-related decisions.

Similarly, in “Foetal Images,” Rosalind Pollack Petchesky argues that ultrasound images and similar technology have played a significant role in the anti-abortion movement in the United States and Britain. Petchesky points to “The Silent Scream,” a 1984 pro-life propaganda piece which shows an abortion through ultrasound imagery. The video has been heavily criticized by the medical community for the misleading use of special effects and inaccurate information about a fetus’ capability to perceive pain and danger. Petchesky argues the movement from the still image of the ultrasound to a real-time video gave those images “an immediate interface with electronic media,” transformed anti-abortion rhetoric from a religious to a “medical/technological mode,” and brought fetal imagery “to life” (in The Gendered Cyborg, 2013).

While these new technologies give a greater sense of empowerment to women, they are skewed by cultural understandings of birth and pregnancy. As such, there is ongoing debate as to whether new reproductive technologies give more or less control to women throughout the reproductive process. Petchesky asks

How are we to understand this contradiction between the feminist decoding of male “cultural dreamworks” and (some) women's actual experience of reproductive techniques and images? (2013)

Petcheskty draws three main conclusions from this debate:

- We have to centralize women within pregnancy and create images that recontextualize the fetus, “that place it back into the uterus, and the uterus back into the woman’s body and her body back into its social space.”

- “We need to separate the power relations within which reproductive technologies, including ultrasound imaging, are applied from the technologies themselves.”

- We must develop “a feminist ethic of reproductive freedom that complements feminist politics.” This means constructing a “joyful sense of childbearing and maternity” that does not “reduce women to a maternal essence.”

(2013)

Reproductive technologies remain a widely discussed area in cyberfeminist discourses. Technology surrounding contraception, abortion, and pregnancy have led to numerous debates surrounding traditional gender roles, motherhood, and the division of parental labor.

Cyberfeminist art

Women’s relationship with cyberspace and technology is not only articulated in academic writing — it can also be found in digital and interactive art, as we have already seen with VNS Matrix.

Other examples of cyberfeminist art include Linda Dement’s Cyberflesh Girlmonster (1995), which was a computer-based interactive work. Dement’s artwork featured images of body parts from around 30 women, accompanied by audio snippets, to create monstrous feminine forms. Another example includes Cornelia Sollfrank’s Female Extension (1997), a computer programme which created a list of over two hundred fictional, female artists to be entered into an art competition. As a result, more than two-thirds of the competition’s entries were from female artists. Despite the high volume of (albeit fictional) female artists, the prizes went to male artists instead. The piece acts as a reflection on gender inequality within the art industry.

Criticisms of cyberfeminism

While cyberfeminism has had a significant impact on gender studies and continues to be a fruitful field of research, there have been numerous issues raised against certain scholars within the field regarding the utopian vision of cyberspace, the gender binaries constructed by cyberfeminists, and generalized statements regarding gender.

Rosi Braidotti argues that there is a gap between the utopian vision of a gender-free cyberspace and the reality of marginalized individuals on the internet. Braidotti writes,

One of the great contradictions of virtual reality images is that they titillate our imagination, promising the marvels and wonders of a gender-free world while simultaneously reproducing notably some of the most banal, flat images of gender identity, but also of class and race relations that you can think of. (“Cyberfeminism with a Difference,” 1996)

Faith Wilding further challenges cyberfeminism’s representation of the internet as a space which disrupts gender relations. In “Where is the Feminism in Cyberfeminism?” (1998), Wilding argues that Sadie Plant overemphasizes the role of women in the technology sector. Wilding asks why so many women occupy teletyping and low-skilled teleoperator roles, as opposed to a minor percentage who work as software designers and computer programmers (in Feminist Art Theory, 2015).

Judy Wajcman critiques this utopian vision of the internet depicted by cyberfeminists. Wajcman examines Plant’s Zeroes + Ones, in which men are “ones,” (i.e, “the singular male identity against which female identity is measured”) and women are zeroes (i.e., nothing). (TechnoFeminism, 2013) On Plant’s metaphor and her distinction between genders, Wajcman writes

Rather than wanting to erase gender difference, Plant positively affirms women’s radical sexual difference, their feminine qualities. It is a version of radical or cultural feminism dressed up as cyberfeminism and is similarly essentialist. The belief in some inner essence of womanhood as an ahistorical category lies at the very heart of traditional and conservative conceptions of womanhood. (2013)

Judy Wajcman

Rather than wanting to erase gender difference, Plant positively affirms women’s radical sexual difference, their feminine qualities. It is a version of radical or cultural feminism dressed up as cyberfeminism and is similarly essentialist. The belief in some inner essence of womanhood as an ahistorical category lies at the very heart of traditional and conservative conceptions of womanhood. (2013)

Trevor Scott Milford further argues that cyberfeminism more broadly has a habit of accepting, rather than critiquing, “simplistic binary notions relating to gender,” including “online vs. offline, virtual spaces as liberating vs. constraining, virtual experience as vulnerable vs. empowering, and regulatory approaches to virtual issues that focus on policy responses vs. self-regulation” (“Revisiting Cyberfeminism,” in eGirls, eCitizens, 2015). This further reinforces the gender binaries that cyberfeminism claims cyberspace can help to negate.

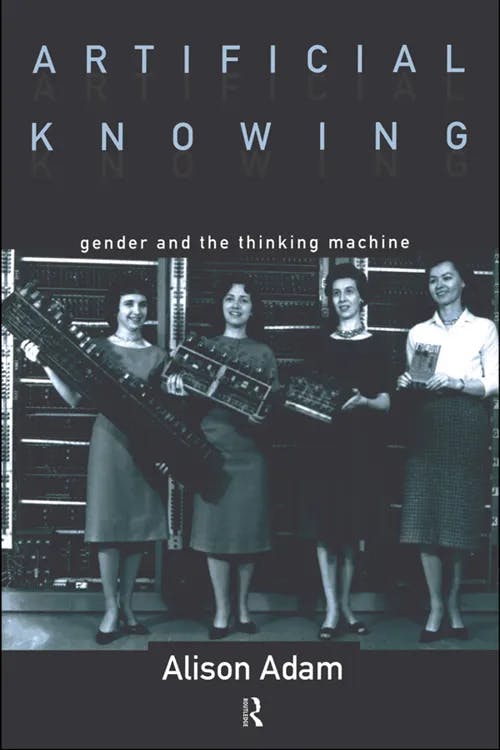

Alison Adam raises another criticism of cyberfeminism: that Plant’s writing has a “universalizing tendency” (Artificial Knowing, 2006). Adam points to several studies on women in technology that are not referenced by Plant, which contradicts her central arguments on the prominence of women online. Adam writes,

The lack of reference to these or any studies like them makes it difficult to know who are the women about which Plant is talking. This is a pity, given the rather pleasing image that she creates of women subverting the Internet towards their own ends. (2006)

Alison Adam

The lack of reference to these or any studies like them makes it difficult to know who are the women about which Plant is talking. This is a pity, given the rather pleasing image that she creates of women subverting the Internet towards their own ends. (2006)

Again, this accusation of generalization is not solely levied at Plant. In “Neither Cyborg Nor Goddess: The (Im)Possibilities of Cyberfeminism,” Stacy Gillis argues that cyberfeminism has not engaged properly with “the material and historical conditions of the human/technological interface,” and that it naively makes the assumption that “gender politics do not exist online and that the sexed embodiment materialised by gender are suspended” (Third Wave Feminism, 2007).

Cyberfeminism now

With so much of our lives conducted online, and more women using the net than ever before, particularly as content creators, it is clear that cyberfeminism still has an important role to play in our society today. Gamergate in 2014–15 (an online harassment campaign against female diversity within gaming culture) is just one example of the misogyny still rampant on the net which attempts to preclude women from engaging online. Jacqueline Ryan Vickery and Tracy Everbach’s edited collection Mediating Misogyny (2018) addresses gender inequality online, including harassment in sports journalism, on fandom sites, and social media trolls.

New studies have also used the ideas of cyberfeminism, but adapted them to be more inclusive. Kishonna L. Gray, for example, has constructed a model for Black cyberfeminism which aims to address:

- “social structural oppression of technology and virtual spaces”

- “intersecting oppressions experienced in virtual spaces”

- “the distinctness of virtual feminism.”

(“‘They’re just too urban’” in Digital Sociologies, 2016).

In the same edited collection, Tressie McMillan Cottom argues for the power of Black feminism to “[offer] a more cohesive intersectional project than cyberfeminism” (“Black cyberfeminism,” 2016).

As Paasonen points out,

Cyberfeminism has an important legacy in media art and activism, and the term continues its viral existence in scholarly writing. [...] Rather than writing manifestos, or investigating virtual spaces or future embodiments, cyberfeminists have become concerned with specific location-based practices, social hierarchies, and global inequalities [...]. (2010)

We can see cyberfeminism’s global reach in Radhika Gajjala’s Digital Diasporas, 2019, which explores technology and gender in India.

Wilding suggests that the next step forward for cyberfeminism is “a collaboration between academic feminist theorists, feminist artists, and popular women’s culture on the Net” to “[visualize] and interpret new theory, and circulate it in accessible popular forms” (1998). This has been achieved somewhat in the twenty-first century due to the availability of research on cyberfeminism online, through accessible articles, video content, and info-activism like Mindy Seu’s The Cyberfeminism Index (2022). The Index details major cyberfeminist works from the 1980s to now, and first began as a viral Google Sheet in 2019. As Seu put it in an interview in 2021, “cyberfeminism feels like a co-authored, rhizome that is built by the people who need it” (“Mindy Seu: cyberfeminism ‘has shifted from utopia to dystopia’”, Dazed).

Further reading on Perlego

Cyberfeminism and Artificial Life (2003) by S. Kember

Feminism Confronts Technology (2013) by Judy Wajcman

Gender and Technology (1999), edited by Caroline Sweetman

Life on the Screen (2011) by Sherry Turkle

Virtual Gender: Technology, Consumption and Identity Matters (2005) by Alison Adams and Eileen Green

Cyberfeminism FAQs

What is cyberfeminism?

What is cyberfeminism?

Who are some key cyberfeminists?

Who are some key cyberfeminists?

What was VNS Matrix?

What was VNS Matrix?

Bibliography

Adam, A. (2006) Artificial Knowing: Gender and the Thinking Machine. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1626718/artificial-knowing-gender-and-the-thinking-machine-pdf

Braidotti, R. (1996) “Cyberfeminism with a difference,” New Formations, vol. 29.

Consalvo, M. (2002) “Cyberfeminism,” in Jones, S. (ed.) Encyclopedia of New Media: An Essential Reference to Communication and Technology. Sage Publications, Inc. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1005413/encyclopedia-of-new-media-an-essential-reference-to-communication-and-technology-pdf

Daniels, J. (2013) Rethinking Cyberfeminism(s): Race, Gender, and Embodiment,” in Wyer, M. et al. (eds.) Women, Science, and Technology. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1614426/women-science-and-technology-a-reader-in-feminist-science-studies-pdf

Deepwell, K. (ed) (2022) 50 Feminist Art Manifestos. KT Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/4188993/50-feminist-art-manifestos-pdf

Dewey, C. (2014) “The only guide to Gamergate you will ever need to read,” Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-intersect/wp/2014/10/14/the-only-guide-to-gamergate-you-will-ever-need-to-read/

Firestone, S. (2015) The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution. Verso. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/731006/the-dialectic-of-sex-the-case-for-feminist-revolution-pdf

Gajjala, R. (2019) Digital Diasporas: Labor and Affect in Gendered Indian Digital Publics. Rowman & Littlefield International. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/969664/digital-diasporas-labor-and-affect-in-gendered-indian-digital-publics-pdf

Gillis, S. (2007) “Neither Cyborg Nor Goddess: The (Im)Possibilities of Cyberfeminism,” in Gillis, S., Howie, G., and Munford, R. (eds.) Third Wave Feminism: A Critical Exploration. 2nd edn. Palgrave Macmillan. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3505248/third-wave-feminism-a-critical-exploration-pdf

Gray, K. L. (2016)“‘They’re just too urban’: Black gamers streaming on Twitch,” in Daniels, J., Gregory, K., and McMillan Cottom, T. (eds.) Digital Sociologies. Polity Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3533168/digital-sociologies-pdf

Haraway, D. (2013) “The Cyborg Manifesto,” in Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1609659/simians-cyborgs-and-women-the-reinvention-of-nature-pdf

Haraway, D. (2013) The Virtual Speculum in the New World Order,” in Hovenden, F. et al (eds.) The Gendered Cyborg: A Reader. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1597927/the-gendered-cyborg-a-reader-pdf

Jones, S. (ed.) (2002) Encyclopedia of New Media: An Essential Reference to Communication and Technology. Sage Publications, Inc. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1005413/encyclopedia-of-new-media-an-essential-reference-to-communication-and-technology-pdf

McMillan Cottom, T. (2016) “Black cyberfeminism: Ways forward for intersectionality and digital sociology,” in Daniels, J., Gregory, K., and McMillan Cottom, T. (eds.) Digital Sociologies. Polity Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3533168/digital-sociologies-pdf

Merck, M. and Sandford, S. (eds.) (2010) Further Adventures of The Dialectic of Sex: Critical Essays on Shulamith Firestone. Palgrave Macmillan. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3479050/further-adventures-of-the-dialectic-of-sex-critical-essays-on-shulamith-firestone-pdf

Milford, T. S. (2015) “Revisiting Cyberfeminism: Theory as a Tool for Understanding Young Women’s Experiences” in Bailey, J. and Steeves, V. (eds.) eGirls, eCitizens. University of Ottawa Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/667394/egirls-ecitizens-pdf

Nakamura, L. (2013) Cybertypes: Race, Ethnicity, and Identity on the Internet. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1616820/cybertypes-race-ethnicity-and-identity-on-the-internet-pdf

Paasonen, S. (2010) “From Cybernation to Feminization: Firestone and Cyberfeminism,” in Merck, M., and Sandford, S. (eds.) Further Adventures of The Dialectic of Sex: Critical Essays on Shulamith Firestone. Palgrave Macmillan. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3479050/further-adventures-of-the-dialectic-of-sex-critical-essays-on-shulamith-firestone-pdf

Petchesky, R. P. (2013)“Foetal Images: The Power of Visual Culture in the Politics of Reproduction,” in Hovenden, F. et al (eds.) The Gendered Cyborg: A Reader. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1597927/the-gendered-cyborg-a-reader-pdf

Plant, S. (1996) “The Future Looms: Weaving Women and Cybernetics,” in Featherstone, M., and Burrows, R. (eds.) Cyberspace/Cyberbodies/Cyberpunk: Cultures of Technological Embodiment. Sage Publications Ltd. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/863378/cyberspacecyberbodiescyberpunk-cultures-of-technological-embodiment-pdf

Plant, S. (2016) Zeroes + Ones. Harper Collins.

Plant, S. (2013) “On the Matrix: Cyberfeminist Simulations,” excerpted in Hovenden, F. et al (eds.) The Gendered Cyborg: A Reader. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1597927/the-gendered-cyborg-a-reader-pdf

Russell, L. (2020) Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto. Verso. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1692968/glitch-feminism-a-manifesto-pdf

Seu, M. (2022) The Cyberfeminism Index. Inventory Press.

Wajcman, J. (2013) TechnoFeminism. Polity. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1535174/technofeminism-pdf

Wilding, F. (2015) “Where is the Feminism in Cyberfeminism,” in Robinson, H. (ed.) Feminist Art Theory: An Anthology 1968 - 2014. 2nd edn. Wiley.

Wolmark, J. (1999) Cybersexualities: A Reader in Feminist Theory, Cyborgs and Cyberspace. Edinburgh University Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1708366/cybersexualities-a-reader-in-feminist-theory-cyborgs-and-cyberspace-pdf

Vickery, J. R., and Everbach, T. (2018) Mediating Misogyny. Gender, Technology, and Harassment. Palgrave Macmillan. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3495061/mediating-misogyny-gender-technology-and-harassment-pdf

VNS Matrix (1991) “A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century.” Available at: https://vnsmatrix.net/projects/the-cyberfeminist-manifesto-for-the-21st-century

VNS Matrix (2022) “Bitch Mutant Manifesto,” in Deepwell, K. (ed.) 50 Feminist Art Manifestos. KT Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/4188993/50-feminist-art-manifestos-pdf

Interviews

Roux, L., and Seu, M. (2021) “Mindy Seu: cyberfeminism ‘has shifted from utopia to dystopia,’” Dazed. Available at: https://www.dazeddigital.com/life-culture/article/58024/1/the-cyberfeminism-index-mindy-seu-liara-roux

Other media

Cyberflesh Girlmonster (1995) Created by Linda Dement. Available at: http://www.lindadement.com/cyberflesh-girlmonster.htm

Female Extension (1997) Created by Cornelia Sollfrank. Available at: http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/works/female-extension/images/4/

The Silent Scream (1984) Directed by Jack Dabner.

PhD, English Literature (Lancaster University)

Sophie Raine has a PhD from Lancaster University. Her work focuses on penny dreadfuls and urban spaces. Her previous publications have been featured in VPFA (2019; 2022) and the Palgrave Handbook for Steam Age Gothic (2021) and her co-edited collection Penny Dreadfuls and the Gothic was released in 2023 with University of Wales Press.