![]()

1

Innumerable Inscrutable Habits: Why Unremarkable Things Matter

How do we see the world as the social science observer does? When you are studying your own society, much of what you see around you may seem ‘obvious’, existing as a mere unnoticed backdrop to your life. So it is tempting to take many things for granted. This temptation is supported by the swiftly changing images we absorb on the Internet and at the movies.

A method used by anthropologists can help us to slow down and look around rather more attentively. When we study familiar situations and events, we can try to make a mental leap and assume that we are observing the behaviour and beliefs of an unknown tribe. The shock in seeing the world as ‘anthropologically strange’ can help us find our feet.

This is not a new strategy. In the 1930s, some British anthropologists invented an innovative method to study everyday life. Instead of relying on their own observations or doing a quantitative social survey, they recruited 50 helpers through a letter in the press. These volunteers were asked to supply the following:

- a short report on themselves

- a description of their environment

- a list of objects on their mantelpieces (i.e. above their fireplaces)

- a day survey which provided an account of all that they saw and heard on the twelfth day of the month.

This form of research became known as Mass Observation. A contemporary newspaper reported the success of its first project:

Six months after the first meeting, Mass Observation was able to organise a national survey of Britain on Coronation Day. A team of 15 reported on the procession, while from provincial towns and villages reports came in on local celebrations. From these ‘mass observations’, the first full-length book has been compiled. (Manchester Guardian, 14 September 1937)

Eventually Mass Observation had about 1500 active observers sending in day surveys. Here is one extract from a coal miner’s description of his day reported by the same newspaper:

At about 12.30 we received a visit from the deputy [i.e. supervisor]. He led off examining our place: it comprises about 50 yards of coalface. My eye follows where his Bull’s-eye [miner’s headlamp] flashes. He asks what I intend to do at this place, or what is required at that place. I differ with him on one point, and state my method. We argue for a short while, he from the point of view of a breakdown in ventilation. We finally agree, and with a final Do this, and that, and that, and that! he leaves us. We are clothed in a pair of boots, stockings, and a pair of knickers, just around our middles. Perspiration rolls off us, our knickers are wet, of time we have no knowledge. If we continue as we are doing, we shall have a good shift. My six pints of water is being reduced, had better go steady.

Notice the degree of detail in this ordinary coal miner’s observations. It is doubtless true that repeated viewings of a video of him at work with his mates would reveal more fine detail. Nonetheless, his account provides excellent observational data which stimulates further questions for investigation. For instance, what shapes his sense of ‘a good shift’? Is his team paid by results or is he just concerned with doing his job well or in a happy spirit?

Let us move on from this thoughtful miner. In the rest of this chapter, I’ll be using the technical term ‘ethnography’ rather than ‘observation’ to describe what many qualitative researchers do. No need to panic. Ethnography simply puts together two different words: ‘ethno’ means ‘folk’ or ‘people’, while ‘graph’ derives from ‘writing’. Ethnography refers, then, to highly descriptive writing about particular groups of people.

In what follows, I’ll try to find inspiration for the ethnographer in the work of writers and two photographers. I’ll then circle back to the brilliant (sadly overlooked) programme for ethnography that the American sociologist Harvey Sacks laid out in his lectures at the University of California some 40 years ago.

Looking at photographs

Why consider photographs in a chapter on ethnography? A good answer is contained in the following extract from an exhibition of one photographer’s work:

Diane Arbus was committed to photography as a medium that tangles with the facts. Her devotion to its principles – without deference to any extraneous social, political or even personal agenda – has produced a body of work that is often shocking in its purity, in its bold commitment to the celebration of things as they are. (Arbus, 2005)

Like Arbus’s photography, I believe that ethnography could have no better aim than ‘to tangle with the facts … without deference to any extraneous social, political or even personal agenda’. Today this view is contested by those who seek to advance their own political and personal agenda and question whether there can ever be any such things as ‘facts’. In Chapter 5, I will discuss their arguments and show why I believe them to be misguided.

As I will try to demonstrate in this chapter, good ethnography, like Arbus’s work, is ‘often shocking in its purity, in its bold commitment to the celebration of things as they are’. Pursuing this line in a school essay written when she was 16 years old, Arbus wrote ‘I see the divineness in ordinary things’.

What is involved in seeing ordinary things as ‘divine’? In 1963, in a successful application for a Guggenheim Fellowship, Arbus wrote this brief note about her interests entitled ‘American rites, manners and customs’. It was the inspiration for the title of this chapter:

I want to photograph the considerable ceremonies of our present because we tend, while living here and now, to perceive only what is random and barren and formless about it. While we regret that the present is not like the past, we despair of its ever becoming the future, its innumerable inscrutable habits lie in wait for their meaning. I want to gather them like somebody’s grandmother putting up preserves because they will have been so beautiful. (Arbus, 2005)

Arbus noted that we usually perceive the world around us as, among other things, ‘random and formless’. About the same time, the Austrian social philosopher Alfred Schutz was writing that the everyday world is necessarily taken for granted. Setting aside these habits is the key to the ethnographic imagination.

What is involved in treating our ‘innumerable inscrutable habits’ as ‘grandmother’s preserves’ which are ‘beautiful’ objects? Like the good ethnographer, Arbus wants us to see the remarkable in the mundane.

Let me illustrate this with one of her photographs (I will have to describe this photograph for you as I have been unable to obtain permission to reproduce it here. If you are interested, you can find it in the exhibition catalogue Revelations, mentioned earlier: Arbus, 2005). The photograph has the caption ‘A family on their lawn one Sunday in Westchester, N.Y. 1968’. The photo shows a couple lounging on deck-chairs in the summer sun while their child plays behind them. In one sense, this could not be a more mundane setting. However, like all of Arbus’s images, we are invited to construct many narratives from what we see. If you had the photograph in front of you, you might ask: ‘Why is nobody speaking or even engaged in eye contact?’ Each person seems self-absorbed. It is not clear whether the man in the picture is shielding his eyes from the sun or indicating a kind of despair.

But we do not need to psychologise our interpretation or to construct a closed narrative. Arbus also asks us to consider a basic ethnographic question: ‘How far does routine family life depend on such silences?’ Implicitly, she reminds ethnographers that this sort of question is only available from observation and hence unlikely to be generated by interviews with family members.

So what is everyday family life actually like? The Israeli photographer Michal Chelbin is a good guide. Like Arbus, to whom she refers, her aim is to remind us of the remarkable in the mundane world. As she puts it:

I am drawn to fantasy and fantastic elements in real environments … Many viewers tell me that the world discovered in my images is strange. If they find it strange, it is only because the world is indeed a strange place. I just try to show that. (Chelbin, 2006: www.michalchelbin.com, Artist Statement)

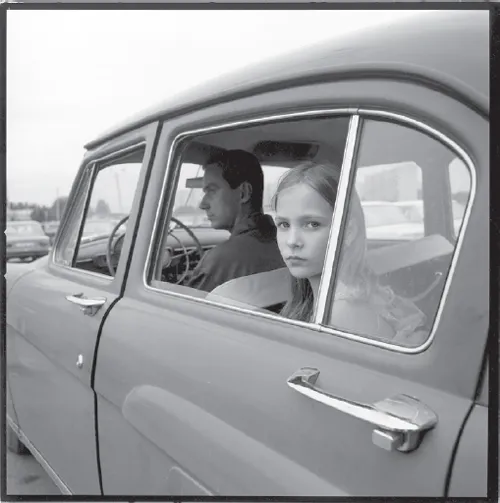

A case in point is provided by a Chelbin photograph called ‘Alicia, Ukraine 2005’.

Alicia stares out at us from the back of her car. Her gaze is ambiguous. Is she a child appealing for our help or a young adult asserting her independence both from us and the driver? Is the man in the front of the car her father or simply a taxi driver?

In a web commentary on these issues in 2006, Eve Wood suggests one answer:

[R]evealed in this young woman’s face is the haughtiness of youth, masking a deeper, more complex awareness of the difficulties in being so young and so beautiful. The girl seems to know something we do not and were we to discover her secret, she might come undone. (Wood, 2006: www.nyartsmagazine.com/index)

Does this photograph show, as Wood suggests, ‘the haughtiness of youth’ and a young woman who is aware of ‘being so young and beautiful’? Chelbin herself tells us of the danger of trying to construct a definitive account of her images. As she puts it: ‘In my work, I try to create a scene where there is a mixture of straight information and riddles.’

Figure 1.1 Alici, Ukraine, 2005

To what extent should the ethnographer try to resolve such riddles? In one of his lectures, Harvey Sacks (1992) offers a case where you observe a car drawing up near you. A door opens and a teenage woman emerges and runs a few paces. Two other people (one male, one female) get out of the car. They run after the young woman, take her arms and pull her back into the car which now drives off.

Now clearly there are several different interpretations of what you have seen. Is this a kidnapping which you should report to the police? Or have you just seen a family row, in which case going to the police might turn you into a busybody?

Sacks expands on the problems this creates for the ethnographer:

Suppose you’re an anthropologist or sociologist standing somewhere. You see somebody do some action, and you see it to be some activity. How can you go about formulating who is it that did it, for the purposes of your report? Can you use at least what you might take to be the most conservative formulation – his name? Knowing, of course, that any category you choose would have the[se] kinds of systematic problems: how would you go about selecting a given category from the set that would equally well characterise or identify that person at hand? (Sacks, 1992, 1:467–8)

Sacks shows how you cannot resolve such problems simply ‘by taking the best possible notes at the time and making your decisions afterwards’ (1992, 1:468). Whatever we observe is impregnated by everyday assumptions and categories (e.g. kidnapper, family member). Rather than lazily employ such categories, Sacks tells us that the task of the ethnographer is to track which categories laypersons use and when and how they use them.

This raises a crucial question. To assemble information on laypersons’ use of categories, do we need to get inside their heads (e.g. to interview them)? This is a big topic which comes to the fore in Chapter 2. At this stage, I will simply suggest that we can often find evidence of category use without needing to ask the people concerned. Think of the terms used by the Mass Observation coal miner to describe his working day. Or consider the rich texture of police reports of kidnappings and/or family disputes or of how they themselves interview witnesses and suspects. Such information constitutes fascinating material on how in real time, in situ, people collaboratively give meaning to their worlds.

The remarkable in the mundane

To look at the mundane world really closely can generate boredom. We think nothing is happening and prefer some ‘action’. If we want to be a good ethnographer, the trick is to go beyond such boredom so that we can start to see remarkable things in quite mundane settings.

The early plays of Harold Pinter strike many people as boring in this sense. Take the opening scene of his play The Birthday Party. We are in the living-room of a house in a seaside town. Petey enters with a paper and sits at the table. He begins to read. Meg’s voice comes through the kitchen hatch as follows:

| Meg: | Is that you, Petey? |

| | [Pause] |

| | Petey, is that you? |

| | [Pause] |

| | Petey? |

| Petey: | What? |

| Meg: | Is that you? |

| Petey: | Yes, it’s me. |

| Meg: | What? [Her face appears at the hatch] Are you back? |

| Petey: | Yes. |

| | (Pinter, 1976: 19) |

‘Where’s the action here?’, we might ask, particularly as much of the first act is composed of such everyday dialogues. Instead of launching us into dramatic events, Pinter writes a dialogue far closer to the tempo of everyday life. Because their expectations of ‘action’ have been disappointed, many people find the first act of The Birthday Party incomprehensible or just plain boring.

But recall Arbus’s depiction of a silent family or Chelbin’s photograph of a young woman silently looking out at us. In your own home, do your mother and father sometimes become obsessed in their own single projects and fail to listen to what others are saying? Perhaps Pinter, like Arbus, is pointing to the major role that mutual inattention plays in family life?

Moreover, this is not simply a psychological question about family dynamics. Pinter’s opening scene reveals something basic to all interaction among families and otherwise. We all tacitly understand that we need to grab somebody’s...