![]() Part I

Part I

Role of RE in Society Today![]()

Chapter 1

The Effective Teacher of RE

‘Education is not about skills and jobs; it is part of a quest for truth . . . It seems glaringly evident that what competes with the open search for knowledge is not the perspective of committed belief, but the closed mind of boredom.’ (Elaine Storkey)1

What makes a good teacher of RE? We explore the question of commitment and openness, and suggest a six-fold approach to valuing as the essential basis for effective education. This can help teachers marry professionalism with values with which they engage personally and publicly. We then relate these values to the teaching of RE.

The most fundamental factor in effective RE, as in the effective teaching of any other subject, is the teacher. Guidelines, syllabuses, books, aids of various kinds, all depend upon the teacher who actually applies them within the classroom situation. The same topic, with the same age and ability range of pupils, and the same general style and method of teaching, can yield entirely different results, depending upon the teacher. One lesson can really take off, and another be dead. For a good teacher is able to establish rapport with pupils and infectiously share enthusiasm for the subject.

Is Religious Faith a Hindrance or an Asset for RE?

The question of a teacher’s commitment is a crucial one. It used often to be assumed that a religious person would teach RE better than someone who is an atheist or agnostic. But that depends on the nature and content of the commitment. A religious person who is extremist or narrow-minded, uninterested in views different from his/her own, may do much damage and close off pupils’ incipient interest in religion and capacity to think intelligently and sensitively about it.

A case is sometimes made for a position of agnosticism as being one which is most congenial to teaching with openness. We know some excellent teachers of RE who would see themselves as agnostic. But a dogmatic kind of agnosticism is also possible: agnosticism just as much as religious faith rests on its own assumptions which can betray key-hole vision. Furthermore, a strong case can be made for arguing that religious commitment is the only way to understand the depths of religion which from the outside may remain sheer enigma. As in the teaching of science or music, for example, the scientist or the musician has normally far more to offer than the non-scientist or the non-musician.

Experience and knowledge of the subject obviously yield dividends in the classroom. Especially in secondary schools, considerable sophistication is called for in order to sustain the interest of older and often religiously alienated pupils. In both primary and secondary schools there is a need for as highly qualified teachers as possible to act as coordinators, helping and encouraging those whose main expertise lies elsewhere. The website accompanying this book will have material to help specialist teachers of various kinds. RE does, however, have to call on the services of many non-specialist teachers, that is, some teachers in secondary schools, and most teachers in primary schools.

We would like therefore to reassure them, as well as those specializing in the subject, that most teachers who are willing to try to teach RE well can do so. For if education includes enabling pupils to take responsibility for their own ongoing self-education through life, the more limited experience that the teacher may have can nevertheless be deployed in a professionally helpful way. This can happen if the teacher has a willingness to engage at some depth with the concepts, ideas and questions evoked by the material, together with a desire to give space to pupils to think for themselves rather than presuming their agreement with everything that is taught. Above all, a teacher needs to model the kind of reflectiveness and weighing of issues which is expected of pupils.

Basic Attitudes Essential for Both Specialist and Non-Specialist RE Teachers

This kind of character and professional behaviour results from holding certain fundamental values. It is important to discuss what these are. A major weakness of what is usually dubbed ‘the Western liberal tradition’ is a certain incoherence about fundamental values. It tends to see values such as tolerance, freedom for self-expression, and equality as fundamental, and yet they are not. For their desirability rests on their conforming to something more deep-seated. Thus tolerance of intolerance is a dangerous contradiction enabling the intolerant to use the tolerance of others as a stepping-stone to power. Similarly, much self-expression is at the expense of the self-expression of others, thereby rendering some people more equal than others, as George Orwell famously put it in Animal Farm.2

In the last two decades there has been more concern to find a common basis for our pluralist society by identifying shared values. Thus the 1999 National Curriculum Handbooks for Primary and Secondary Teachers lists these as The Self, Relationships, Society, and The Environment.3 The non-statutory national framework for RE sees these basic values as ‘truth, justice, respect for all and care of the environment’.4

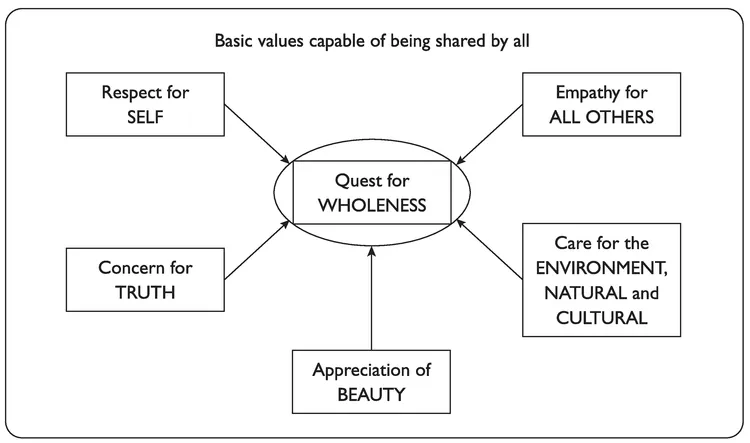

Values may be expressed in many different ways, and we respond in the following way to the excellent work which has so far been done (see Figure 1.1). Three from the Handbooks’ list appear to be the same, although the gloss on them is different in some respects. But we miss out Society and put Truth as a separate value, for to subsume the latter under Society makes a mockery of what we mean by Truth: truth relates to reality as it is, not just to how any particular group of people think it is. Truth is especially important for understanding religion which sees a supreme place in the scheme of things for God or the Transcendent. Religious people claim that God does exist and is not just a figment of their imagination.

Truth is present in the framework list, as is respect for all which is understood to include oneself. We feel, however, that there is a need specifically to distinguish the self from others. We consider that justice is an inherent part of respect in that to be unjust towards others is to fail to show them respect. We also widen the valuing of the environment to include human traditions and cultures.

To both lists we add beauty, because valuing the aesthetic dimension to life contributes so much to civilized life and well-being. Similarly, beauty relates to that sense of awe

Figure 1.1 A six-fold approach to valuing

and wonder which is so often lacking when people talk about God as though God is just a human concept.

A list by itself is inadequate to convey the real import of each value. We therefore give more detail on how we understand the six-fold approach to valuing.

1 Self-respect – a basic self-affirmation and awareness, concern for integrity and openness to guard against prejudice and delusion. A certain self-respect is crucial, for without respecting the one person one is with all the time and can know from the inside, what possibility is there of respecting anyone else? But this self-respect must be more than simple self-esteem or a ‘feel-good’ factor. Respect for oneself acknowledges also limitations, difficulties and failures and the need for criticism. We need to affirm ourselves, but critically. (See discussion of this on pp. 8, 63–5 and 133–5.)

2 Respect for all other people – a basic attitude of empathy towards others and generous-mindedness towards what is especially meaningful to them. It is very important to understand that there must be respect for all others, not just for those whom we happen to like or whose opinions agree with ours, nor just for those who wield power or are gifted with charisma. In meetings of all kinds, for example, this translates into respect not just for the dominant member of the group, nor just for people immediately present, but also for the people who will be affected by any decision made or not made.

3 Respect for the environment natural and cultural – a basic care for the natural world and interest in diverse human traditions with concern to play fair with them. This valuing involves acknowledging that people are part of these worlds, each with their own autonomy yet powerfully influencing one another. It helps to guard against two dangerous misunderstandings: regarding nature as just to be used by humans, and being dismissive towards human traditions which may seem strange or uncongenial.

4 Respect for beauty – a basic sense of wonder and awareness that there is more to life than the mundane, pragmatic and purely factual. The word beauty suggests a heightened awareness and delight in qualities such as shape, proportion and colour which the environment, either natural or manufactured, can display. Quite apart from the vexed question as to whether beauty is in the eye of the beholder or whether it has objective reality, the appreciation of beauty has been one of the hallmarks of every civilization.

5 Respect for truth – a basic search for truth, that is, for what actually is the case, seeking to avoid ignorance, misunderstanding and falsehood. Truth is fundamental for without it there can be no respect for the self that one really is, for other people as they are, or for the world which happens to be in existence. Even awareness of beauty is, for most writers, artists and musicians, in a deep sense linked to awareness of how things actually are. Chesterton once spoke of it like this: ‘The startling wetness of water excites and intoxicates me; the fieriness of fire, the steeliness of steel, the unutterable muddiness of mud.’5 The pursuit of knowledge understood as the opposite of ignorance, blindness and delusion is central to education and to being a person.

6 Respect for wholeness – a basic concern for seeing the inter-connectedness of everything and a desire to sort out contradictions, not resting satisfied with fragmented and perhaps schizophrenic understanding. It is important to appreciate that the other five basic values are not in watertight compartments but constantly interact. The search for wholeness reinforces each one without marginalizing any; it asks what makes most sense of the totality of experience without, so far as possible, ignoring any aspect of life.

Openness and commitment

In some ways the word openness can pinpoint this six-fold approach to valuing, but only provided that openness is not misunderstood. It can very easily be taken as meaning sitting on the fence about anything controversial, or as refusing to hold any strong convictions. But of course belief in the importance of openness is itself a conviction, and one normally held very strongly today! Furthermore, life does not permit us the luxury of constant academic neutrality in an ivory tower. Decisions have to be made on one basis or another. Not to choose is in fact to choose in a weak and unintended form, just as failing to answer a letter is itself answering it. True openness is paradoxically only possible on the basis of firm convictions. The opposite of firm commitment is not no commitment but a confusion of weakly held or conditioned commitments, mostly unarticulated and imprecise.

Education cannot avoid advocacy as well as elucidation, but if the values it encourages are educationally valid, as we believe those we are advocating are, there need be no fear of inappropriate influencing by the teacher. As far back as 1955 M.V.C. Jeffreys summed up what was needed: ‘The guarantee of freedom is not the teacher’s neutrality, but his or her respect for the integrity of the pupil’s personality.’6

What therefore will save teachers from unacceptable dogmatism, whether of a religious or non-religious nature, is not the absence of commitment even were this possible, but the integrity with which the teacher pursues and models such openness. Teachers are then able, as Edward Hulmes has argued, to use their own commitment regarding religion as a valuable resource.7 (See Figure 3.3 and further discussion on pp. 46–8.)

What RE can do to Implement these Values

Whether formally qualified in RE or not, the effective teacher in the classroom will seek to exemplify such values in relation to RE. We discuss these in some detail below.

The list may appear daunting and unattainable, especially in view of the enormous pressures placed on teachers in today’s schools. Research undertaken by Mark Chater into teachers’ vocations and values 1997–20048 suggests how risky and fragile an enterprise it is to sustain personal commitment of this nature in the over-bureaucratic, efficiency-dominated atmosphere which tends to pervade the education system in the UK. We hold, howe...