![]()

| 1 | From Albazin to Nagasaki |

| Russia’s first contacts with China and Japan, 1685–1813 |

To share a continent: Russia and China, 1685–1727

Red-haired barbarians on the Amur

In 1686 the Manchu emperor Kangxi, 32 years old and in the twenty-fifth year of his reign, sent a letter to the Muscovite co-tsars and half-brothers Ivan V, aged 20, and Peter I, aged 14. It had been 40 years since the Manchu had conquered Ming China and founded the Qing Empire; these same decades had also seen rapid Russian expansion into Siberia and the Far East. The fortress towns of Albazin and Nerchinsk in the Amur River Valley — territory the Chinese ruler considered to be his rightful domain — were clear evidence of the Russian presence.1 After a salutation from the Chinese emperor to the “great white Lords, two brothers, Tsars and autocrats,” the letter proceeds directly to the matter at hand, namely Kangxi’s siege of Albazin in the summers of 1685 and 1686. In a tone mixing frustration and lofty condescension, the emperor tells the co-tsars about his decision to attack the Russian settlement: although Kangxi, as “Lord of all the regions of the Earth beneath the Sky, reigning over far-distant places,” desired “that [each nation] should live according to his lot in peace,” he was compelled to destroy the Russian garrison because “your people living in [Albazin]” “attack[ed] without cause our unarmed subjects” and “constantly [gave] refuge to our runaways.” Most pointedly, the letter states:

Those dwelling on your frontier have not made known to you, Changa [White] Khan, my will and intentions, though I have repeatedly complained by letter, stating that your Russians, roving up and down, create disturbances and trouble, violating my frontiers, of which it seems you were quite ignorant.2

At once a complaint and imperious admonition to the young Russian tsars to pay more attention to their eastern frontiers, Kangxi’s letter illustrates the tentative and haphazard beginnings of Russo-Chinese relations. At the end of the seventeenth century, Russia and China, each knowing little of the other, gradually found themselves sharing a continent.

Karl Marx once remarked that “the relations of Russia to the Chinese Empire are altogether peculiar.”3 Marx was referring to the overland connection of Russia and China, a condition that altogether set Russia apart from the maritime experience of the West’s discovery of the Middle Kingdom. What made Russia unique in relation to Asia — its exposure to the complex history of struggle and conquest between nomadic and sedentary societies and between various Asian peoples — was also what distinguished its encounter with China. That the steppe was the prism through which Russia first viewed the Middle Kingdom is seen in the Russian word for China, “Kitai.” The term refers not to the Han, the dominant group native to China, but to Khitan, the name of a Mongolic-speaking nomadic people who conquered northern China in the tenth century and established the Liao Dynasty (907–1125).4 When in the mid-seventeenth century Russians sought direct contact with the Asian state, yet another non-Chinese group, the Manchu, a Tungusic-speaking people, had begun to rule China. Having founded the Qing Dynasty in 1644, the Manchu outsiders themselves adopted the traditional Sinocentric worldview that posited the state as the “Middle Kingdom,” the “Central State” whence civilization emanated to the steppe and other “barbarians” outside its territory. From the time of young Peter to the reign of Catherine II (1682–1796), Russia persistently sought to develop diplomatic and economic relations with China. This period, which saw the rise of Russia as a European power and its greatest territorial expansion, coincided in China with the era of “Great Peace,” so called by Chinese historians to refer to the political stability, cultural flourishing, and maximum westward expansion achieved under the Manchu emperors Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong (1667–1796).

The “contact zone” wherein the two expanding empires met was the Amur River and the surrounding region of Manchuria.5 Originating at the confluence of the Shilka and Argun rivers (where the Republic of Mongolia adjoins Chinese Inner Mongolia), the Amur River dips south and east to form the 2,600-mile border dividing Russia and China today, before curving dramatically upwards near Khabarovsk and emptying itself into the North Pacific by way of the Tatar Straits. The river is known to the Chinese as the “Black Dragon River” (Heilong Jiang) and the Mongolians as the “Black River” (Khara-Muren) owing to the amount of sediment darkening its waters. Long before the Russian advance in the seventeenth century, Manchuria and the Amur was a place of mythical and national significance for the peoples of northeast Asia. The home of various Tungusic and Mongolic-speaking peoples, parts of the region were ruled throughout the centuries by the Chinese, the Koreans, the Khitan, the Mongols, and, in the seventeenth century, the Manchu. This last group not only considered Manchuria their ancestral birthplace, but also believed the Black Dragon River to be sacred. At times perceived by East Asians as a frontier space akin to the American Wild West, from the late nineteenth to the beginning of the twentieth century Manchuria would become the site of intense national and imperial conflict, as seen in the activities of the government of Nicholas II or the formation of the Japanese ultra-nationalist group the “Black Dragon Society” (Kokuryukai, 1901).6

But for the Russian governors (voevody) of Siberia and their Cossack explorers and fur traders (promyshlenniki) in the early 1600s, the Amur basin was simply empty space waiting to be explored, a natural extension of the Siberian conquests spearheaded by daredevil adventurers like Yermak in the previous century. In 1644 (at about the same time as the Manchu conquered China), Vasily Poyarkov became the first Russian to explore the Amur. Little is known of Poyarkov’s background; he makes his first appearance in historical records when, under orders from the governor of Yakutsk Petr Golovin, the Cossack fur trader led an expedition in search not only of sources of fur, but also, more urgently, grain and food supplies to feed the Russian population in Yakutsk and other settlements in Siberia. Aside from this pioneering move, Poyarkov is remembered for his cruel treatment of the Daurians, a Mongolic-speaking people inhabiting the area. Relentless in demanding tribute (yasak) in the form of fur from the Daurians, Poyarkov responded to native resistance with brutality. When faced with hunger, the Russians even resorted to eating Daurian captives by roasting their flesh, behavior which planted among the local peoples an indelible first impression of Russians as cannibals.7

Harsh winter and starvation forced Poyarkov to retreat in 1646, but he was soon followed by Yerofei Khabarov, the colorful Cossack explorer and entrepreneur whose fame is celebrated in the Far Eastern city that bears his name. Hailing from the Vologda region, Khabarov, like Yermak, worked for the Stroganovs in the salt mines in his youth. Khabarov’s ambition for fortune and fame led him in the 1640s to the fur-trapping business in Siberia, and, in the years 1649–53, to carry out two expeditions to the Amur River. It was Khabarov who cemented the Russian presence in the region by converting Albazin, a Daur village, into a Russian fortress (1651).8 It was also Khabarov who first prompted the Qing to take note of the Russians in the Amur, as the local peoples began to appeal to the Qing concerning their ruthless behavior. Encountering the Russians, the Chinese described them, as they did other Westerners, as fierce-tempered, bellicose, “barbarians” with big noses, red hair, and green eyes.9 Perhaps based on Daurian accounts of Russian cannibalism, they also dubbed them men-devouring locha, a Chinese word meaning “demon.”10

The reckless self-confidence of the Cossacks in relation to the Daurians was based on the Russian experience of easy victories over indigenous peoples in the East ever since Yermak’s defeat of Kuchum Khan in 1582.11 In the Chinese, however, the Russians found a formidable force. Although the first military clashes in the 1650s resulted in retreat by the Qing, thereby buoying Russian confidence in their hold on the region, by 1685 Kangxi’s bannermen had destroyed Albazin. One consequence of the Albazin attack was the capture of about 50 Russians who were taken to China and made to settle there. Kangxi personally took an interest in the “surrendered locha” and had them form the Bordered Yellow Banner, one of the Eight Banners constituting the Manchu military. Hoping to win Russian compliance with an additional strategy of enticement, he made it a point to treat the Albazinians (Albazintsy) as he did his Qing bannermen by providing them with housing, rank, wives, and the right to practice their religion.12

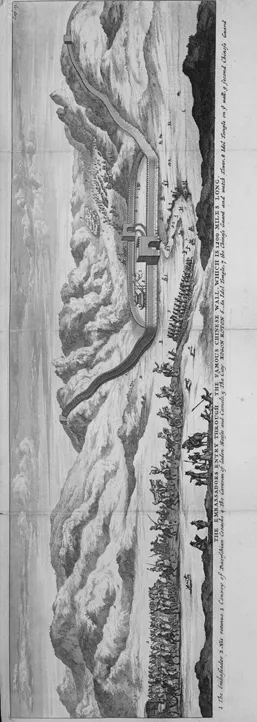

Figure 1.1 The Russian Embassy led by Izbrants Ides passes through the Great Wall (1692–96).

Credit: Evert Izbrants Ides, Three Years Travels from Moscow over-land to China: through Great Ustiaga, Siriania, Permia, Sibiria, Daour, Great Tartary, etc. to Peking (London: W. Freeman, 1706), 60.

General Research Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations

While the advance to the Amur was being carried out with little Russian awareness of its eastern neighbor, authorities in Siberia and Moscow had meanwhile begun to open their eyes to the prospect of trading with China. It prompted Moscow to begin sending envoys to the Central State. The first Russian mission dates as far back as 1618, when the first Romanov tsar Mikhail Fyodorovich dispatched a group led by Ivashko Petlin, a Cossack from Tomsk, “to make enquiry as to the kingdom of China and to see the Tsar [Chinese emperor].”13 Petlin’s expedition traveled across Siberia and Mongolia, following the Great Wall for ten days before entering China, then under Ming rule. Like Marco Polo in the thirteenth century, Petlin was deeply struck by what he saw in the Middle Kingdom. His 1619 report of the mission, the first Russian eye-witness account of China, is characterized by images of bustling, animated cities that beckon and dazzle the observer with possibilities of trade and commerce. Abundance and variety are main themes, as seen in Petlin’s repetition of the words “all kinds” (the adjective vsiakii):

The shops are of stone painted in all colors (kraskami vsiakimi) […] and all kinds of goods are there (tovary …vsiakie) […] and all kinds of flowers and different kinds of sugar, cloves, cinnamon […] and shop rows in the town with all sorts of wares […].

Petlin described Beijing as a great city as “white as snow,” the Forbidden City as the “Magnet City.” In the latter, a place “where the Chinese Tsar Taibun himself dwells,” “beautified with all sorts of wondrous things,” Petlin spent a mere four days.14 Having brought no gifts of tribute, the Russians were not allowed an audience with the emperor.

The Chinese relationship to the outside world was based uncompromisingly on the Sinocentric worldview. Foreign envoys were received only on the condition that they present their country as a vassal of China, and were required to perform the ketou before the emperor (or kowtow, the act of bowing low by touching the head to the ground) in addition to presenting tribute gifts.15 Chinese insistence regarding this protocol and the Russian refusal to follow it continued to be an issue in the missions following Petlin’s. The bigger problem, however, lay in the fact that the two Russian goals — the penetration of the Amur, on the one hand, and trade with China, on the other — were (at least from the Chinese perspective) mutually exclusive; in order to attain one, Russians had to give way in the other. The response of the Manchu to these Russian goals was entirely shaped by their concerns over the balance of power in Eurasia. As seen in the complaint concerning runaways in Kangxi’s letter, the entrance of the Russians into the Amur region threatened to upset Qing hegemony in relation to their tributary peoples in north and central Asia. Because of these conflicting goals, early Russo-Chinese encounters before the Nerchinsk Treaty (1689) were often characterized by communication at cross-purposes. This was the cause of the failures of seventeenth-century Russian embassies to China, such as those led by Fyodor Baikov (1656) and Nikolai Milescu (Spathary) (1676).16 Receiving the Russians in Beijing as envoys from the country of “Aloso” (or “Oloso,” the Chinese rendering of the word “Rus’” via the Mongolian pronunciation “Oros”), Qing leaders at first failed to understand that they hailed from the same country as the locha they had encountered in the Amur. Both Baikov and Milescu refused to perform the ketou; both also merely continued to press the Chinese for trade, even as they dismissed repeated Qing requests for the Russian withdrawal from the Amur and the return of the fugitives.

The prominence of fugitives in Russo-Chinese relations of this period underscores the significant role played by steppe peoples such as the Soluns and the Mongols. Caught between a rock and a hard place, Inner Asians not surprisingly sought to balance the two powers to their advantage and thereby served as catalysts in Russo-Chinese exchange. Their presence also reveals that in spite of the fact that the Russians and the Chinese considered the other thoroughly alien, as sedentary civilizations flanking the Eurasian steppe the two sides had more in common than they realized in terms of their historical interaction with and perception of Inner Asia. In the mid-thirteenth century, Russia and China were conquered by the Mongols and absorbed into different parts of a single Mongol empire: Russia into the Kipchak Khanate in the northwest, China into the Yuan Dynasty in the southeast. They also shared the notion of Mongols and pastoral peoples in general as being less civilized. The origin of the word “Tatar,” that all-encompassing term used by Russians, at least well into the nineteenth century, to refer to most (if not all) Asian peoples, has its origin in the ninth-century Chinese word “dada,” the Chinese name for the pastoralist tribes of the north. With the Mongol invasion, the term trickled into Europe, where it was moreover combined with “Tartarus,” the Latin term for hell: hence “Tartar.” In Russia “Tatar/Tartar” came to be used...