- 632 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Ecological Design and Planning Reader

About this book

From Henry David Thoreau to Rachel Carson, writers have long examined the effects of industrialization and its potential to permanently alter the world around them. Today, as we experience rapid global urbanization, pressures on the natural environment to accommodate our daily needs for food, work, shelter, and recreation are greatly intensified. Concerted efforts to balance human use with ecological concerns are needed now more than ever.

A rich body of literature on the effect of human actions on the natural environment provides a window into what we now refer to as ecological design and planning. The study and practice of ecological design and planning provide a promising way to manage change in the landscape so that human actions are more in tune with natural processes. In The Ecological Design and Planning Reader Professor Ndubisi offers refreshing insights into key themes that shape the theory and practice of ecological design and planning. He has assembled, synthesized, and framed selected seminal published scholarly works in the field from the past one hundred and fifty years——ranging from Ebenezer Howard's Garden Cities of To-morrow to Anne Whiston Spirn's, "Ecological Urbanism: A Framework for the Design of Resilient Cities." The reader ends with a hopeful look forward, which suggests an agenda for future research and analysis in ecological design and planning.

This is the first volume to bring together classic and contemporary writings on the history, evolution, theory, methods, and exemplary practice of ecological design and planning. The collection provides students, scholars, researchers, and practitioners with a solid foundation for understanding the relationship between human systems and our natural environment.

A rich body of literature on the effect of human actions on the natural environment provides a window into what we now refer to as ecological design and planning. The study and practice of ecological design and planning provide a promising way to manage change in the landscape so that human actions are more in tune with natural processes. In The Ecological Design and Planning Reader Professor Ndubisi offers refreshing insights into key themes that shape the theory and practice of ecological design and planning. He has assembled, synthesized, and framed selected seminal published scholarly works in the field from the past one hundred and fifty years——ranging from Ebenezer Howard's Garden Cities of To-morrow to Anne Whiston Spirn's, "Ecological Urbanism: A Framework for the Design of Resilient Cities." The reader ends with a hopeful look forward, which suggests an agenda for future research and analysis in ecological design and planning.

This is the first volume to bring together classic and contemporary writings on the history, evolution, theory, methods, and exemplary practice of ecological design and planning. The collection provides students, scholars, researchers, and practitioners with a solid foundation for understanding the relationship between human systems and our natural environment.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

Historical Precedents

Introduction to Part One

In the early nineteenth century, many visionary thinkers espoused various ideas about how humans and other organisms relate to nature, thus establishing the rudimentary foundations of contemporary ecological planning and design.1 Knowledge of these relationships has been used by the general public and professionals in a variety of fields as a means of justifying the decisions they make about the use of the landscape, such as allocating natural resources for the exclusive use of humans; as a mandate for moral action; as an aesthetic norm for beauty; and as a reliable source of scientific evidence to guide future uses.2 These various ways of employing the knowledge of these relationships are intertwined. I will attempt to unfold them as I sketch the history of ecological planning.

Early urban civilizations, especially those of classical Greece and Mesopotamia, viewed nature as a wild beast to be tamed. For instance, the prominent Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 B.C.) and the early Stoics claimed that nature was a resource for the exclusive use of humans.3 In contrast, another noted Greek philosopher Plato (422–347 B.C.), who was a mentor to Aristotle, lamented the loss of the verdant hills and forests within the fertile Mediterranean basin surrounding Athens that occurred during that era as a result of deforestation for shipbuilding and fuel. He cautioned:

To command nature, we must first obey her.4

Even during that era, twenty-five centuries ago, Plato understood the significance of the interdependent relationships between people and nature, which essentially is ecology as we know it today. He urged us to seek understanding of the intrinsic and intimate dimensions of these relationships—the essence of the place—and to employ the resultant knowledge in making decisions about the alternative futures of landscapes. Plato’s insights are timeless.

Fourteenth-century Italian artists depicted through their paintings that the landscape’s intrinsic and aesthetic values could be appreciated for pleasure. This was contrary to earlier medieval beliefs about hidden fears associated with unknown nature.5 Many English landscape gardeners and painters portrayed landscapes as being both productive agriculturally and yet beautiful to behold. This sort of English landscape has become idealized as a beautiful landscape and has formed the image that has inspired much of Western landscape design.6

Appreciation of the beauty of the natural environment was also clearly evident in the writings of nineteenth-century visionary thinkers in the United States, such as Catlin, Emerson, Thoreau, and Muir. These visionaries alerted us to the fact that the beauty of a landscape is a function of its natural character, a thinking that is widely prevalent today. The more natural, the more beautiful! Indeed, some contemporary architects, designers, and planners employ naturalistic themes in many ways as an authority to justify the incorporation of nature or ecological ideas and insights into the design and planning decisions they make.

Transition from Agrarian to Industrial Economy

The coming of the industrial economy in the United States and Europe brought about major shifts in population dynamics, growth, and migration. From the late 1800s through the early 1920s, employment in industry grew slowly initially but increased rapidly after the 1870s. By 1850, the U.S. population was 23.19 million, representing a 337 percent increase from 1800. The accelerating population growth, especially evident after the Civil War, coincided with a massive migration of population from rural areas to cities. By 1920, the U.S. population was 106 million, a 357 percent increase over the 1850 census. For the first time, the U.S. population residing in urban areas, at 51 percent, surpassed those living in rural areas at 49 percent. This period coincided with the westward expansion of the American frontier.

Increased population growth and dispersal intensified pressures on urban landscapes to accommodate people’s needs for food, work, shelter, and health. Unfortunately, many urban areas did not have adequate human and physical infrastructure or resources to accommodate the new growth. Urban sprawl and blight became the order of the day, causing prime agricultural lands and resources to be converted haphazardly into urban uses. Agriculture as a source of employment lost its local market and declined as an occupation. Rural areas became severely impoverished. The degradation of forest resources, decreased water quality, and soil erosion were rampant.

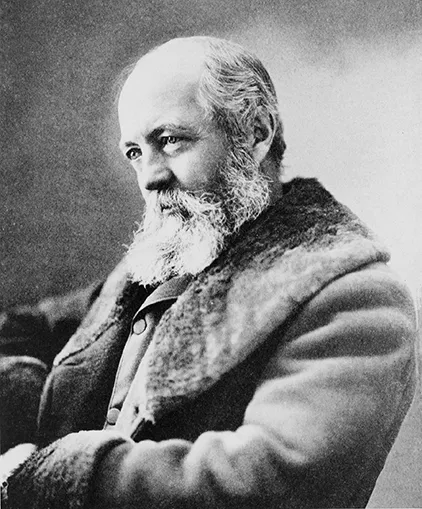

Cultural, artistic, and intellectual movements emerged as reactions against the erosion of traditional values, the fragmentation of the closely knit social structures of agricultural communities, and the destruction of valued resources in rural landscapes. It was within this sociocultural, economic, and political context that many visionary thinkers emerged and expressed their concerns about the deteriorating quality of life in both urban and rural areas. They romanticized the richness, beauty, and moral order the natural landscape provided. Through their works, including philosophical statements, paintings, poetry, and designed works, thinkers such as Emerson, Thoreau, Marsh, and Olmsted put forth powerful arguments about the felt need to preserve and conserve the natural landscape (figure 1-1).

The readings in part 1 of this book illuminate key ideas and important contributions in the evolution of ecological planning. It is not feasible to include readings from all these visionary thinkers in the historical account presented here. As a result, the readings may best be viewed as an outline map, offering an overview of the historical foundations. I invite the reader to explore the notes at the end of each reading, which provide references for more detailed readings on the subject.

Readings

Except for the essay from David Lowenthal, the first five of the six essays in the section are classics on the historic foundations of ecological planning and environmental thinking, presented here in a historical sequence. The last one is an important work on the subject that summarizes key themes in the history and explores the future of ecological planning. In the first reading, “Higher Laws,” originally published in Walden; or, Life in the Woods (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1854),7 eighteenth-century visionary thinker, poet, and philosopher Henry David Thoreau documented his experiences over a two-year period (1845–1847) in a cabin near Concord, Massachusetts. He argued forcefully that active experiential engagement was a superior way of knowing, and in particular, of understanding nature and achieving true humanity. The book is regarded as an American classic that “explores natural simplicity, harmony, and beauty as models of just social and cultural conditions.”8

George Perkins Marsh’s 1864 timeless masterpiece Man and Nature; or, Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action is the next reading.9 In the introductory chapter, he examines how human actions can dramatically destroy the landscape and advocates the possibility of restoration as a solution. No person before Marsh was more effective in arguing that culture was an integral part of, and not distinct from, nature. As a result, he laid the foundational ideas about what would eventually become the conservation movement that began in the early 1900s. Excerpts of the original chapter appear, as it is too extensive to be included in its entirety. To better appreciate the richness of his contributions and better understand the importance of their originality, I also include the “New Introduction” to the 2003 edition, written by David Lowenthal, a distinguished historical geographer and the world’s leading scholar on George Perkins Marsh.10

Figure 1-1 Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. (Photo from http://blog.chicagodetours.com/2013/02/riversides-story-as-the-first-planned-suburb).

The next reading is “The Town-County Magnet” in Ebenezer Howard’s influential and visionary book To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Reform (1898), republished four years later, in 1902, as Garden Cities of To-morrow.11 Howard (1850–1928) was an English proponent of the garden city concept. His book laid out a powerful vision for how to best accommodate urban growth by combining the essences of urban and country life in a harmonious, interdependent way. The impact of Howard’s contribution was immense. Lewis Mumford (1895–1990), a philosopher, social historian, and cultural critic, noted in 1944 that “Garden Cities of To-morrow has done more than any other single book to guide the modern town planning movement and to alter its objectives.”12 He contended that the originality of Howard’s contribution was in his “character synthesis . . . of the interrelationship of urban functions within the community and the integration of urban and rural patterns, for the vitalizing of urban life on one hand and the intellectual and social improvement of rural life on the other.”13 In short, Howard examined rural and urban improvement as a unified problem.

Scottish botanist and urban planner Patrick Geddes’s work follows. Geddes is credited with providing the intellectual basis for a regional survey approach. His article “The Study of Cities” from his seminal book Cities in Evolution: An Introduction to the Town Planning Movement and to the Study of Civics (1915) is presented here. In the article, Geddes introduced a “method of civic study and research, a mode of practice, and application.”14 His approach was founded on science but grounded in empirical observations of a place to illuminate the relations among culture, work, and environment (“folk-workplace”). Revealing these connections implies an understanding of the ecological relationships among the folk-work-place attributes, even though he did not explicitly use the term ecology.

Geddes encouraged the use of civic surveys, which included documenting and visualizing the regional landscape. He urged citizens to study the resources of the region “with utmost realism, and then seek to preserve the good and abate the evil with the utmost realism.”15 Geddes’s approach may be summed as an artistic yet technical reading of the existing conditions in regions.16 Today, Geddes’s folk-work-place attributes are remarkably similar to ideas embedded in the widely known concept of sustainability.

Next is a classic from regional planner Benton MacKaye. He was a champion of primeval landscapes and father of the Appalachian Trail, a 2,000-mile wilderness hiking trail through the Appalachian Mountains. His condensed article, “Regional Planning and Ecology,” provides the much-needed conceptual linkages among regions, planning, and ecology in a succinct and persuasive narrative.17 He argued that the sprawling expansion of metropolitan areas, and especially the outward flow of population, resulted in the degradation of valued natural resources—“its material resources, its energy resources, and its psychological resources.”18 He believed that conservation, or the sustained use of natural resources, was crucial in finding solutions to the sprawling expansion of the metropolis. MacKaye explicitly linked regional planning to ecology, and more specifically to human ecology.

The last article is “Ecological Planning: Retrospect and Prospect,” written by Frederick Steiner, Gerald Young, and Ervin Zube, which appeared in Landscape Journal in 1988.19 It provides a condensed account of the historical foundations of ecological planning until the mid-1980s, identifies the major themes from both theory and practice, and evaluates the continued evolution of the field. It is the only article in the book so far that synthesizes key national and state legislation and policy formulated to balance human use with environmental concerns.

Although not included in the readings because of space constraints, two articles on history are worthy of mention. The first is Harvard professor emeritus Carl Steinitz’s survey of the history of influential ideas in landscape planning, published in 2008.20 The other is “Ecological Planning in a Historical Perspective,” published in 2002, which is a succinct summary of the historical developments in ecological planning from the early to mid-1800s to the late 1990s. In fact, it expands upon numerous ideas from the previous article, updating them to the early 2000s.21 I also review contemporary forces influencing the continued advancement of the field. I end the article by asserting that ecological planning, or at least its theoretical dimension, has advanced rapidly in North America. Yet it still remains an unfinished, evolving field and an uncharted territory for rigorous scholarly work.

Notes

1. Forster Ndubisi, Ecological Planning: A Historical and Comparative Synthesis (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), 35.

2. Anne Whiston Spirn, “The Authority of Nature: Conflict, Confusion, and Renewal in Design, Planning, and Ecology,” in Ecology and Design: A Framework for Learning, Kristina Hill and Bart Johnson (eds.), (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2001), 21–49.

3. Derek Wall, Green History: A Reader in Environmental Literature, Philosophy and Politics (London: Routledge, 1994).

4. Alexander Pope quoted in Frederick Steiner, The Living Landscape: An Ecological Approach to Landscape Planning, 2nd ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1999), 187; also in Benton MacKaye, “Regional Planning and Ecology,” Ecological Monographs 10 (1940), 340.

5. Aesthetic means “appreciative of the beautiful” (Merriam-Webster Dictionary). Aesthetic experiences “deal with the subjective thoughts, feelings, and emotions expressed by an individual during the course of an experience.” Richard Chenoweth and Paul Gobster, “The Nature and Ecology of Aesthetic Experiences in the Landscape,” Landscape Journal 9, no. 1 (1990), 1–8. Aesthetic experiences are an important aspect of people-landscape interactions.

6. Carl Steinitz, “Landscape Planning: A History of Influential Ideas,” Journal of Landscape Architecture 3, no. 1 (2008), 74.

7. Henry David Thoreau, “Higher Laws,” in Walden; or, Life in the Woods (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1854).

8. “Henry David Thoreau,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_David_Thoreau, accessed March 1, 2013.

9. George Perkins Marsh, Man and Nature; or, Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action (New York: Charles Scribner, 1864).

10. David Lowenthal, “New Introduction,” in Man and Nature, by George Perkins Marsh. David Lowenthal (ed.), (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2003).

11. Ebenezer Howard, Garden Cities of To-morrow (Being the Third Edition of “To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform”) (London: S. Sonnenschein & Company, Limited, 1902).

12. Lewis Mumford, “The Garden City Idea and Modern Planning,” in Garden Cities of Tomorrow, reprinted in 1944 (Great Britain: Faber and Faber Ltd.), 29.

13. Ibid., 35.

14. Patrick Geddes, Cities in Evolution: An Introduction to the Town Planning Movement and to the Study of Civics (London: Williams & Norgate, 1915), 320.

15. Philip Boardman, The Worlds of Patrick Geddes: Biologist, Town Planner, Re-educator, Peace Warrior (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978), 14.

16. Emily Talen, New Urbanism and American Planning: The Conflict of Cultures (London: Routledge, 2005).

17. Benton MacKaye, “Regional Planning and Ecology,” Ecological Monographs 10, no. 3 (1940), 349–53.

18. David Startzell, “Foreword,” in The New Exploration: A Philosophy of Regional Planning, by Benton MacKaye (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1990).

19. Frederick Steiner, Gerald Young, and Ervin Zube, “Ecological Planning: Retrospect and Prospect,” Landscape Journal 7, no. 1 (1988), 31–39.

20. Steinitz, “Landscape Planning: A History of Influential Ideas,” 74.

21. Ndubisi, “Ecological Planning in a Historical Perspective,” in Ecological Planning: A Historical and Comparative Synthesis (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), 9–33.

Higher Laws

Walden (1854)

Henry David Thoreau

As I came home through the woods with my string of fish, trailing my pole, it being now quite dark, I caught a glimpse of a woodchuck stealing across my path, and felt a strange thrill of savage delight, and was strongly tempted to seize and devour him raw; not that I was hungry then, except for that wildness which he represented. Once or twice, however, while I lived at the pond, I found myself ranging the woods, like a half-starved hound, with a strange a...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- About Island Press

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part One: Historical Precedents

- Part Two: Ethical Foundations

- Part Three: Substantive Theory

- Part Four: Procedural Theory

- Part Five: Methods and Processes

- Part Six: Dimensions of Practice

- Part Seven: Emerging Frameworks

- Conclusion: Maintaining Adaptive and Regenerative Places

- Copyright Information

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Ecological Design and Planning Reader by Forster O. Ndubisi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.