![]()

1

“A Feeling of Belonging”

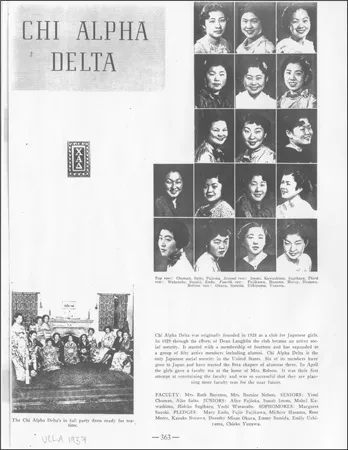

Chi Alpha Delta, 1928-1941

Spring 1941. The sun sparkles and the flowers glow against the terracotta-colored brick buildings at the University of California, Los Angeles. Imagine, if you will, that you are a new member of the sorority Chi Alpha Delta. You have just been initiated into membership with your eager pledge class and have just discovered that your sorority has the campus’s highest grade point average.1 For your first Spring Formal dance, your sorors suggest smooth dates, rejecting all drips, and propose a shopping trip to pick out snazzy shoes in which to groove the night away. You have just been reprimanded for whispering too loudly in College Library, debating which beautician could best help you achieve Judy Garland–esque permanent waves. But next year you will not be on campus. You are not just any young co-ed at UCLA. You are Japanese American. During spring 1942, instead of hurrying across Royce Quad, exchanging greetings with classmates, you will be stripped of all of your legal rights as an American citizen and summarily incarcerated as a “prisoner without trial” for three years in an internment camp.2

Predominantly second-generation Japanese Americans, members of Chi Alpha Delta spoke English at home and with each other, permanent-waved their hair, wore poodle skirts with saddle shoes, and nicknamed themselves the “Chis.” Like women in European American sororities, they staged barnyard frolics, ski weekends, and beach outings and, at their banquets, savored fried chicken, green beans, and three-layer cake. Yet, to set the mood for their annual outdoor Faculty Tea, the women of Chi Alpha Delta dressed in kimonos and arranged their hair in “Japanese” styles. For public performances, they displayed Japanese ethnic pride and/or “exoticism,” but in their everyday lives they would be as American as their flared skirts and pearl-buttoned sweaters.

A Feeling of Belonging’s story of modernity, gender, and public culture begins with the story of Chi Alpha Delta because Japanese American women represented the first generation of American-born women of Asian descent to attain numerical and cultural significance. Moreover, the 1930s second generation known as the Nisei was unique in American history. In a nation-state that validated racial segregation with the Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the Nisei faced obstacles to claiming their place in America that no other ethnic or racial group had ever faced.3 The 1924 Immigration Act that limited European migration and excluded Asians in actuality targeted Japanese immigration. In addition, California’s alien land laws, which forbade immigrants from owning land, were passed directly against the Japanese. In sum, 1920s American racial hostilities targeted the Japanese as the ultimate non-American aliens. The burden, then, was on the sisters of Chi Alpha Delta and their American-born cohort to prove their American citizenship.

Although activities such as deciding whether to wear poodle skirts or kimonos may appear trivial, against the backdrop of the racial hatreds that made possible Japanese American incarceration during World War II, the stakes were enormous. The social reality of pre–World War II American racial apartheid overshadowed all cultural decisions that young Japanese American women like the Chis faced. As the visible, both in terms of race and in terms of markers such as clothing, was understood as indicating political and national allegiance, public culture was contested terrain. Acts of cultural citizenship ranging from forming a sorority to planning a fox-trot competition at Chi Whoopee demonstrated belonging to American society. Although the members of Chi Alpha Delta did not use the term cultural citizenship to describe their activities, the concept is useful because it shows the cumulative political meaning in quotidian events. Cultural citizenship is defined as everyday practices through which racial minorities and other marginalized groups claim a place in society, which leads to claiming rights.4 Such acts that “claim space in society” are counternarratives to the mainstream construction of racial minorities as unassimilable peoples occupying a liminal space outside the imagined nation-state. Although performing ethnic cultural heritage (kimonos) and modern American culture (poodle skirts and permanent waves) should be seen as mutually constitutive identifi-catory processes instead of oppositional ones, mainstream society frequently conflated homage to Japanese ancestry with loyalty to Japan. For reasons ranging from Japan’s pre–World War II military campaigns in Asia to the bombing of Pearl Harbor, any alleged allegiance to Japan was suspect.

A very rich and complete array of Chi Alpha Delta documents, ranging from minutes of meetings to scrapbooks and oral history interviews, has preserved this story of daily decisions that make up cultural citizenship.5 The prewar records are particularly valuable since few Japanese American institutional records survived World War II internment.6 In addition, since it is exceedingly rare to have access to local sorority records, there has been very little scholarly literature on the history of roughly 3 million women who joined sororities.7 In fact, there is only one in-depth work that focuses on sorority women’s history: journalist Paula Giddings’s In Search of Sisterhood.8 Giddings examines the institutional history of African American sorority Delta Sigma Theta’s national governing board. Instead of national leadership and expansion, local Chi Alpha Delta records reveal the day-to-day struggles over race, class, femininity, and culture.

This chapter, “A Feeling of Belonging,” explores the development of public culture in three interrelated ways. First, I examine the founding of the sorority as an act of claiming a space of belonging in the world of the university. A ringing declaration of cultural citizenship, the creation of an Asian American sorority demonstrates the significance of establishing race-safe spaces in a racially segregated society. Second, I explore the parameters of Chi Alpha Delta’s democratic practices that differentiated them from exclusionary European American sororities. Third, sororities provided numerous opportunities for pleasure, and the women in Chi Alpha Delta used “fun” to play with, explore, and create cultural citizenship practices. In an era of racial segregation, the sorority allowed the women to claim advantages such as glamour, dating, and parties, as well as to create democratic and hybrid cultural forms.9 Though part of an intrinsically heteronormative conservative organization, the women of Chi Alpha Delta nonetheless made visible and called attention to hidden racialized structures within the supposedly democratic nation-state.

“A Feeling of Belonging”: The Rationale for Chi Alpha Delta

In 1928, Helen Tomio Mizuhara and Alyce Asahi founded Chi Alpha Delta at the University of California, Southern Branch, as a haven against racism. In the early years at the university, since Japanese American women faced institutional discrimination and lacked support networks, they wanted an organization to alleviate those problems. In addition, sororities provided material benefits such as student dwellings close to the university. Moreover, many Japanese Americans on campus, in Los Angeles and across the nation, considered sororities prestigious for the social status they accrued to their members. However, Japanese American women were not allowed into European American sororities. Hence Mizuhara and Asahi created an organization of their own.

Fourteen charter members formed the first Japanese American (and Asian American) sorority in the United States. Sponsored by the dean of women, Helen Laughlin, Chi Alpha Delta received official recognition from the university known today as the University of California, Los Angeles, on April 5, 1929. The Los Angeles Japanese American newspaper, the Rafu Shimpo, subsequently reported: “Following the footsteps of the men students, the co-eds of UCLA have organized into a society which is known as the A. O. Society. It is an organization which is open to all of the Japanese women students at the University of California in Los Angeles. The only requirement is the paying of club dues.”10 Like their male counterparts, the Nisei Bruin Club, Japanese American women decided to form a racially exclusive organization.

As oral history interviews reveal, racial discrimination and segregation instigated the founding of Chi Alpha Delta. According to one of the charter members, Shizue Morey Yoshina, since the numbers of Japanese American women who attended the university were few, those women believed they needed a same-sex, same-race organization in order to feel at home at the university. Yoshina described American society in the 1920s as racially polarized: “You have no idea, at the present time, what sort of a wall there was between the whites and anybody else. And it was pretty bad. And all this persisted until World War II. That was a long time coming. So in the meantime we fought our own battle.”11 As a Nisei, a second-generation Japanese American, Yoshina recognized the multitude of laws that restricted citizenship according to race. The 1924 immigration act codified two significant ones.12 First, it curtailed migration from Asia, including Japan. Second, it forbade the immigrant generation, the Issei (the Nisei’s parents), from becoming naturalized American citizens. In addition to national laws, Southern California regulations segregated many popular recreational venues, such as swimming pools and movie theaters.13 In a classic act of cultural citizenship, Yoshina and other Japanese American women fought their own battle against racism by banding together so that they could benefit by strength in numbers.

Chi Alpha Delta Year Book Page, 1937. (Used by permission of the University Archives, UCLA).

Yoshina described the motivations for founding the sorority as being both racially and economically based:

[We] used to get together, see each other in the library. We noticed that all the scholarships, competition for this award and that award all went through the Greek letter organizations. [We had a] Japanese women’s club. But we saw that all the goodies went to the Greek people, and none of us was ever asked to join one of them and we decided to make our own. The reason why we got going was because we just wanted to be able to compete with them.14

Japanese American women were excluded from European American sororities, which had a monopoly on scholarship funds. Yoshina and other charter members wanted equal access to that money. Since the Japanese women’s club at UCLA did not have the same institutional power that a university-sanctioned organization such as a sorority had, Japanese American women realized they could compete for educational funds by starting their own Greek-letter association. Thus cultural citizenship in the guise of sorority participation ensured access to “rights” such as scholarship funding.

Japanese American women’s desire to form a sorority was completely in keeping with the collegiate culture of the times. In the early twentieth century, fraternal organizations proved to be the central social clubs at universities.15 As soon as UCLA was founded in 1919, ten sororities and one fraternity established chapters.16 As a former teacher’s college, the California State Normal School, UCLA was predominantly female until it gained in prestige in the mid-1930s; hence the greater number of sororities. All eleven of the fraternal organizations were locally founded groups that had grown out of social clubs formed at the California State Normal School. The proliferation of sororities was so rapid that by 1929, the year Chi Alpha Delta was recognized as a campus organization and UCLA moved to Westwood, all thirty-eight existing national sororities had chapters at the university. The availability of relatively inexpensive older homes for rent near the old Vermont Avenue campus assisted the sororities’ founding. At UCLA, sororities enjoyed strong membership throughout the prewar years. In 1941, the campus’s chapters claimed 822 members, roughly a quarter of the female student population.17 Judging by their yearbook photograph, that same year Chi Alpha Delta had at least twenty-seven active members.18 Nationally, the number of college and university women who joined sororities is staggering. Between 1851 and 1993, over 2.8 million women joined one of the twenty-six existing National Panhellenic sororities.19

At UCLA and across the nation, sororities were the leading social organizations on campus. For example, The Claw, a UCLA campus magazine that was published for over four decades, glamorized sorority women.20 The periodical frequently profiled rush recruitment by dedicating five or six pages of a fall issue to formal photographs of the newly pledged members smiling triumphantly in their new sorority houses’ parlors.21 A regular column entitled “Glass Houses” discussed dating habits and the social whirl ad nauseam. These types of magazines were not just information sources but arbiters of social standing on campus. They were designed to instill envy in those not in the “in” crowd and to normalize unequal power relations.

As could be expected given the racialized nature of sorority hierarchy, women of color almost never appeared in The Claw. Chi Alpha Delta was represented only once, and only in name. For the December 1934 issue, The Claw’s cover depicted Christmas-present boxes, with each of the campus’s Greek letter organizations appearing on a different box; the picture included a box embossed with the Greek letters Chi, Alpha, and Delta.22 However, that was the only time they ever appeared in the magazine. The fact that it was not a racialized photographic representation of the members probably allowed its inclusion. Given that numerous members of Chi Alpha Delta were Buddhist, inclusion as a symbolic Christmas gift speaks volumes to the Christian assumptions of the Greek system.

In fact, one of the only times an embodied woman of color appeared in The Claw was in a derogatory cartoon. This 1931 image deserves close scrutiny, for it demonstrates how the race, class, and sexual hierarchies embedded within the Greek system became apparent at the cultural level. In the cartoon, an African American woman carrying a load of laundry approaches a streetcar and says to the conductor: “Just a minute, mister, ’till I get my clothes on.”23 While the “mammy” wants the conductor to wait until she gets her load of laundry onto the streetcar, if one did not see the cartoon, one might assume that she was nude. Since she is African American and is drawn with an “Aunt Jemima” figure, she is presumed to be the exact opposite of socially desirable white femininity. Hence the punch line: working-class African American women are not sexually desirable even when naked. Thus the asexual mammy who unintentionally provides the material that others can deride stands as the necessary foil to the blonde sorority woman, who is desirable precisely because she is neither black nor poor nor overweight. The use of this type of racialized caricature showed that universities shared broader American societal mores exemplified by Amos ’n’ Andy cartoons and mammy stereotypes. Such ra...