Biological Sciences

Bacterial Metabolism

Bacterial metabolism refers to the chemical processes that occur within bacteria to maintain life. It involves the conversion of nutrients into energy, the synthesis of cellular components, and the elimination of waste products. Bacterial metabolism can be categorized into different pathways, such as glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation, which play crucial roles in the survival and growth of bacteria.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Bacterial Metabolism"

- eBook - PDF

- Edward Bittar(Author)

- 1998(Publication Date)

- Elsevier Science(Publisher)

These descendants include mammals and, in particular, humans who share many basic metabolic pathways with extant bacteria. A knowledge of Bacterial Metabolism therefore is helpful in understanding basic aspects of human metabo- lism. Familiarity with this subject is also helpful in understanding bacterial infec- tion processes and in the identification of pathogenic bacteria. Bacterial Metabolism has been comprehensively reviewed by Gottschalk (1986), whose book should be consulted for detailed information. CARBOHYDRATE METABOLISM AND ATP PRODUCTION An energy source is needed to fuel most of the life processes of bacteria. For instance, replication of the genetic material, considered by some to be the most basic life process, requires energy. Methods for extracting energy from molecules in the environment probably emerged in protocellular organisms in order to drive genome replication and other processes, such as protection from environmental hazards and the gathering of substrates used as cellular building blocks. In general, those metabolic pathways employed in the synthesis of cellular constituents are referred to as anabolic. These pathways generally require energy input. Degradative pathways are referred to as catabolic. These catabolic pathways include energy yielding processes such as fermentation and respiration. Fermenta- tion is a rearrangement of the atoms of an organic substrate (without net oxidation) which yields useful energy. Respiration ordinarily involves the net oxidation of substrates at the expense of molecular oxygen (although some bacteria use an inorganic electron acceptor other than 0 2 such as nitrate, sulfate, or CO2). Respi- ration is a much more efficient process than fermentation for obtaining useful energy from organic substrates. - eBook - ePub

- Barron's Educational Series, Rene Kratz(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Barrons Educational Services(Publisher)

5Microbial Metabolism WHAT YOU WILL LEARNThis chapter introduces the fundamentals of metabolism, especially as they apply to microbial cells. As you study this chapter, you will: • learn about the ways humans use microbial metabolism; • review how cells transfer energy and electrons; • explore the process of cellular respiration; • compare cellular respiration and fermentation; • discover how microbes make food by photosynthesis and chemolithoautotrophy.SECTIONS IN THIS CHAPTER• Fundamentals of Metabolism• An Overview of Microbial Metabolism• Fundamental Metabolic Pathways of Heterotrophic Metabolism• Fundamental Metabolic Pathways of Autotrophic Metabolism• Anabolic PathwaysCells, whether yours or a microbe’s, are living, growing things. They require energy and materials that can be used as building blocks. We feed our cells by taking food into our mouths and then breaking it down in our digestive system. Once the food is broken down into protein, carbohydrate, and fat molecules, our cells can take in those molecules and use them. Similarly, the cells of microbes may take in food molecules from their environment. If the cells break the molecules down further in order to obtain energy, it is called catabolism . If a cell uses a molecule as a building block to make a larger molecule, it is called anabolism . All of these processes together, the breaking down and the building up, is called metabolism .Metabolism is an amazing thing. At any one time, a cell is performing hundreds of different chemical reactions, breaking down molecules for energy and building molecules it needs to do certain jobs. And when we look at all the types of life on planet Earth, the metabolic champions are the microbes. As a group, microbes are incredibly diverse in their metabolism. They can break down more types of molecules than any other group and produce many different types of molecules as waste.This metabolic diversity of microbes has been used by humans since ancient times. Anything you’ve ever eaten that’s been fermented, like yogurt, wine, or beer, was made with microbial metabolism. Breads and cheeses too require the action of microbes, as do soy sauce, kim chee, sausages, sauerkraut, and kefir. Our use of microbial metabolism goes beyond food. We use microbes to clean up our sewage and other types of pollution like oil spills. In the future, we may be able to make plastics that microbes can eat, eliminating a problem substance in our landfills. Microbes also produce enzymes that are used in laundry detergents and to make products like paper and corn syrup. Microbes make vitamins and are a source of the amino acids used to make artificial sweeteners (aspartame) and MSG. Recently, we’ve even begun to modify microbes by introducing pieces of DNA so that they can make human proteins like insulin and interferon that are used to fight disease. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- The English Press(Publisher)

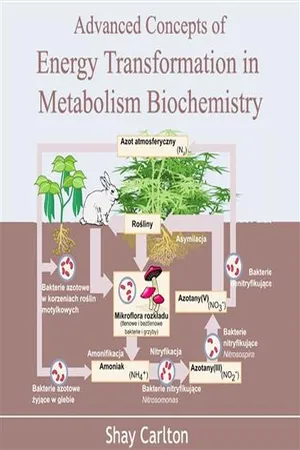

____________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ____________________ Chapter- 4 Microbial Metabolism Microbial metabolism is the means by which a microbe obtains the energy and nutrients (e.g. carbon) it needs to live and reproduce. Microbes use many different types of metabolic strategies and species can often be differentiated from each other based on metabolic characteristics. The specific metabolic properties of a microbe are the major factors in determining that microbe’s ecological niche, and often allow for that microbe to be useful in industrial processes or responsible for biogeochemical cycles. Types of microbial metabolism Flow chart to determine the metabolic characteristics of microorganisms All microbial metabolisms can be arranged according to three principles: ____________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ____________________ 1. How the organism obtains carbon for synthesising cell mass: • autotrophic – carbon is obtained from carbon dioxide (CO 2 ) • heterotrophic – carbon is obtained from organic compounds • mixotrophic – carbon is obtained from both organic compounds and by fixing carbon dioxide 2. How the organism obtains reducing equivalents used either in energy conservation or in biosynthetic reactions: • lithotrophic – reducing equivalents are obtained from inorganic compounds • organotrophic – reducing equivalents are obtained from organic compounds 3. How the organism obtains energy for living and growing: • chemotrophic – energy is obtained from external chemical compounds • phototrophic – energy is obtained from light In practice, these terms are almost freely combined. Typical examples are as follows: • chemolithoautotrophs obtain energy from the oxidation of inorganic compounds and carbon from the fixation of carbon dioxide. - eBook - PDF

Anaerobic Sewage Treatment

Optimization of process and physical design of anaerobic and complementary processes

- Jeroen van der Lubbe, Adrianus van Haandel(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- IWA Publishing(Publisher)

Therefore, anabolism and catabolism are interdependent: catabolism provides the necessary energy for anabolism, and anabolism is necessary for growth, so that the bacterial mass remains, even if there are losses due to predators and decay. Figure 2.1 shows the overall scheme of Bacterial Metabolism. Figure 2.1 also demonstrates another aspect of Bacterial Metabolism. Bacterial decay happens: over time micro-organisms cease to exist as living material. Some of the decayed cell material may be metabolized again, but there is a residue of particulate material that is either not biodegradable or only biodegrades very slowly. This material accumulates in the system as endogenous residue until it is discharged as excess sludge or together with the effluent. This chapter discusses aspects related to the stoichiometry and the kinetics of the metabolic processes that develop in wastewater treatment systems. These aspects are: (1) The ratio between the fractions of organic material used in anabolism and catabolism; (2) Thermodynamic considerations to assess whether catabolic processes can develop; (3) Kinetics, which deals with the rate of processes that develop; and (4) The decay rate of living micro-organisms and the generation of the endogenous residue. Biological treatment systems can be divided into two categories according to the nature of catabolism. In aerobic systems the organic material is oxidized to products like carbon dioxide and water, that is, the organic material is destroyed, having its electrons transferred to the oxidant (which is usually oxygen). In anaerobic systems there is fermentation of organic compounds with some end products that are more oxidized and others more reduced than the original material, in the sense that there are products with greater or lesser potential of electron transfer than the original material. Often anaerobic degradation of organic material does not involve only one fermentation, but a sequence of fermentations. - eBook - ePub

- Tyrrell Conway, Paul S. Cohen, Tyrrell Conway, Paul S. Cohen(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- ASM Press(Publisher)

3 Metabolic Adaptations of Intracellullar Bacterial Pathogens and their Mammalian Host Cells during Infection (“Pathometabolism”) WOLFGANG EISENREICH, 1 JÜRGEN HEESEMANN, 2 THOMAS RUDEL, 3 and WERNER GOEBEL 2 Metabolic adaptation reactions are common when prokaryotes interact with eukaryotic cells, especially when the bacteria are internalized by these host cells. Such adaptations lead to significant changes in the metabolism of both partners. While the final outcome may be sometimes beneficial (e.g., in case of insect endosymbiosis) or (mainly) neutral for the interacting partners (e.g., microbiota and their hosts) (1 – 3), it is usually detrimental in infections of mammalian cells by intracellular bacterial pathogens. In this encounter, a host cell-defense program is initiated, including antimicrobial metabolic reactions aimed to damage the invading pathogen and/or to withdraw essential nutrients, while the intracellular pathogen tries to deprive nutrients from the host cell and to counteract the antimicrobial reactions, resulting in damaging of the host cell. Our knowledge of the metabolic adaptation processes occurring during this liaison and the link between these metabolic changes and the pathogenicity is still rather fragmentary. For these complex metabolic interactions, we coin the term “pathometabolism” - eBook - PDF

- I Rowland(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

1 Methodological Considerations for the Study of Bacterial Metabolism M. E. COATES, B. S. DRASAR, A. K. MALLETT and I. R. ROWLAND A. Introduction Because of the prevailing physicochemical conditions in the gut, particu-larly the low redox potential and low oxygen tension, studies of the gut microflora (whether bacteriological, biochemical or toxicological) require specialized techniques of varying degrees of sophistication and expense. Many of the methods designed for culturing and identifying the component microorganisms of the flora have been extensively reviewed elsewhere and hand-books are available which describe in detail the apparatus, culture media and isolation methods for anaerobic bacteriological studies (Holdeman and Moore, 1975; Mitsuoka et al., 1976; Drasar and Hill, 1974; Brown, 1977; Sutter et al., 1980). The methods used for quantitating these organisms and also for the less fastidious anaerobes and facultative anaerobes are summarized with their advantages and disadvantages in Table 1.1. This review will concentrate on the techniques, in vitro and in vivo, that may be used for studying the role of the flora in metabolism and toxicity of chemicals. B. Studies of Gut Flora Metabolism in vitro 1. Incubation with Gut Contents From Animals and Man (a) Obtaining samples. The most widely used approach is to remove the caecum from the animal immediately after death and express the contents into a suitable suspension medium (see below). In humans a freshly collected sample of faeces can be treated in the same way. How ROLE OF T H E G U T F L O R A IN TOXICITY A N D C A N C E R Copyright © 1988 Academic Press Limited ISBN 0-12-599920-8 All rights of reproduction in any form reserved - eBook - ePub

- Rodney P. Anderson, Linda Young(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

A. faecalis uses a different set of enzymes to catabolize peptone and produces basic by-products that raise the pH and turn the medium blue.The pH indicator in the medium shows differences in the metabolic activities of the bacterial species in the inoculum.Linda YoungThink Critically

You have prepared OF lactose basal medium and inoculated it with E. coli. After incubation, you find that the media has turned yellow. What can you conclude about the bacterium’s ability to catabolize this carbohydrate?Some metabolic reactions are common to all living organisms, whereas other biochemical processes are unique to certain groups. Metabolic diversity is especially impressive in microorganisms such as bacteria (seeThe Microbiologist’s Toolbox). The remainder of this chapter will focus on major metabolic processes and highlight several biochemical reactions that distinguish medically significant bacterial species.1.Howis the energy stored in chemical bonds made useable to cells?2.Whydo anabolic processes require an input of energy to run?7.2 Energy Production Principles

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

1.Outlinethe role of oxidation-reduction reactions in metabolic processes.E2.Explainthe processes that generate ATP and the role of ATP in cellular metabolism. - eBook - PDF

- Gerald Karp, Janet Iwasa, Wallace Marshall(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

CHAPTER OUTLINE 3.1 Bioenergetics 3.2 Enzymes as Biological Catalysts The Human Perspective: The Growing Problem of Antibiotic Resistance 3.3 Metabolism The Human Perspective: Caloric Restriction and Longevity 3.4 Green Cells: Regulation of Metabolism by the Light/Dark Cycle 3.5 Engineering Linkage: Using Metabolism to Image Tumors 100 CHAPTER 3 Bioenergetics, Enzymes, and Metabolism 3.1 Bioenergetics A living cell bustles with activity. Macromolecules of all types are assembled from raw materials, waste products are pro- duced and excreted, genetic instructions flow from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, vesicles are moved along the secretory path- way, ions are pumped across cell membranes, and so forth. To maintain such a high level of activity, a cell must acquire and expend energy. The study of the various types of energy transformations that occur in living organisms is referred to as bioenergetics. The Laws of Thermodynamics Energy is defined as the capacity to do work, that is, the capac- ity to change or move something. Thermodynamics is the study of the changes in energy that accompany events in the universe. The following sections focus on a set of concepts that allow us to predict the direction that events will take and whether an input of energy is required to cause the event to happen. However, thermodynamic measurements provide no help in determining how rapidly a specific process will occur or the mechanism used by the cell to carry out the process. The First Law of Thermodynamics The first law of thermodynamics is the law of conservation of energy. It states that energy can neither be created nor destroyed. Energy can, however, be converted (transduced) from one form to another. The transduction of mechanical energy to electrical energy occurs in the large wind-turbines now being used to generate energy from wind (Figure 3.1a), and chemical energy is converted to electrical energy by gas-powered generators. - eBook - PDF

- Julianne Zedalis, John Eggebrecht(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Openstax(Publisher)

All of the cellular processes listed above require a steady supply of energy. From where, and in what form, does this energy come? How do living cells obtain energy and how do they use it? This chapter will discuss different forms of energy and the physical laws that govern energy transfer. How enzymes lower the activation energy required to begin a chemical reaction in the body will also be discussed in this chapter. Enzymes are crucial for life; without them the chemical reactions required to survive would not happen fast enough for an organism to survive. For example, in an individual who lacks one of the enzymes needed to break down a type of carbohydrate known as a mucopolysaccharide, waste products accumulate in the cells and cause progressive brain damage. This deadly genetic disease is called Sanfilippo Syndrome type B or Mucopolysaccharidosis III. Previously incurable, Chapter 6 | Metabolism 237 scientists have now discovered a way to replace the missing enzyme in the brain of mice. Read more about the scientists’ research here (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/32mpsiiib) . 6.1 | Energy and Metabolism In this section, you will explore the following questions: • What are metabolic pathways? • What are the differences between anabolic and catabolic pathways? • How do chemical reactions play a role in energy transfer? Connection for AP ® Courses All living systems, from simple cells to complex ecosystems, require free energy to conduct cell processes such as growth and reproduction. Organisms have evolved various strategies to capture, store, transform, and transfer free energy. A cell’s metabolism refers to the chemical reactions that occur within it. Some metabolic reactions involve the breaking down of complex molecules into simpler ones with a release of energy (catabolism), whereas other metabolic reactions require energy to build complex molecules (anabolism). A central example of these pathways is the synthesis and breakdown of glucose. - eBook - ePub

- G. H. Chen, Mark C. M. van Loosdrecht, G. A. Ekama, Damir Brdjanovic(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- IWA Publishing(Publisher)

Here we focus on the basic aspects of microbial growth, how it can be monitored and studied, and how it can be mathematically described. It is simply based on how microorganisms derive their cellular energy from chemical redox reactions or alternatively light (catabolism) and how they implement this energy to maintain their cell (maintenance) and build new biomass from the nutrients available (anabolism). Microbial growth systems relate to a trigonal combination of elements, electrons, and energy. On this basis, microbial growth can be formulated as a chemical reaction characterized by stoichiometry (yields), kinetics (rates), and thermodynamics (Gibbs free energy). Essentially any redox reaction that has a negative Gibbs energy can be considered a potential catabolic reaction for energy generation for microbial growth. It is this versatility in converting chemical compounds that is exploited in wastewater treatment.2.1.3 Microbial community engineeringMicrobial community engineering is applied to select the guilds of natural microorganisms that can convert waste compounds into harmless compounds or new resources. The establishment of microbial niches is driven by microbial ecology. A good combination of ecological engineering principles can help to predict the selection and conversion of, and competition between, microorganisms as the basis for process design (Kleerebezem and Van Loosdrecht, 2007; Lawson et al., 2019). Microorganisms are retained in the treatment process as flocs, granules, and/or biofilms. Selective pressures are generated by acting on e.g. the availability of nutrients, electron donors (hereafter referred to as e-donors), most often organic matter, and electron acceptors (e-acceptors) such as dissolved oxygen (O2 ) or oxidized nitrogen compounds (NOx ) such as nitrite (NO2 − ) or nitrate (NO3 − ). These variables are manipulated by WWTP designers and operators to set the conditions necessary to sustain microbial growth and conversions. Additional environmental boundaries can impact bioprocesses, e.g - eBook - PDF

Microbes

A Source Of Energy For 21st Century

- Soni, S.K.(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- NEW INDIA PUBLISHING AGENCY (NIPA)(Publisher)

Hence, the overall reaction in Pseudomonas , using the same dissimilatory pathways as E. coli , is Glucose + 6O 2 6CO 2 + 6 H 2 O + 38 ATP + 688 kcal (total) and the corresponding efficiency is about 45 percent. The pathways of central metabolism (glycolysis and the TCA cycle), with a few modifications, always run in one direction or another in all organisms. Because these pathways provide the precursors for the biosynthesis of cell material. Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway (EMP pathway) or the TCA cycle, not only provide energy but also provide chemical intermediates for the synthesis of cell material. Such pathways are known as amphibolic pathways. The main metabolic pathways, and their relationship to biosynthesis of cell material, are shown in Figure 34. The fundamental metabolic pathways of biosynthesis are similar in all organisms, in the same way that protein synthesis or DNA structure are similar in all organisms. When biosynthesis proceeds from central metabolism as drawn below, some of the main precursors for synthesis of procaryotic cell structures and components are as follows: • Polysaccharide capsules or inclusions are polymers of glucose and other sugars. • Cell wall peptidoglycan (N-acetyl glucosamine; NAG and N-acetyl muramic acid; NAM) is derived from glucose phosphate. 206 Microbes : A Source of Energy for 21st Century Figure 32 Schematic representation of Tricarboxylic acid (TCA) or Kreb’s cycle Figure 33 ATP yield per glucose molecule broken down in aerobic respiration 207 Microbial Metabolism Energy Release and Conservation • Amino acids have various sources. • Nucleotides (DNA and RNA) are synthesized from ribose phosphate. • Triose-phosphates are precursors of glycerol, and acetyl CoA is a main precursor of lipids for membranes. • The main precursors of amino acids for manufacture of proteins are pyruvate, -ketoglutarate and oxaloacetate. • Vitamins and coenzymes are synthesized in various pathways that leave central metabolism. - eBook - PDF

- Anthony Pometto, Kalidas Shetty, Gopinadhan Paliyath, Robert E. Levin(Authors)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

One could even think that a similar approach will also be valid for synthesizing secondary metabolites whose precursors are provided by the glycolytic pathway. A second approach points toward a completely differ-ent direction, the creation of an energy surplus (in contrast to the energy “sink” created in the previous approach). For example, let us consider that the excretion of a certain product P (e.g., an amino acid) is an energy-requiring process. If a condition of energy surplus is created, cells will use any energy consuming process to dissipate the excess of energy, and therefore the secretion of product P will be stimulated. The existence of sequenced genomes for several bacteria involved in producing food ingredients (e.g., Lac. lactis, C. glutamicum, B. subtilis, E. coli ) will dramatically impact ME opportunities. Once genome sequences are available, technologies such as cDNA microarrays can be used to simultaneously monitor and study the expression levels of individual genes at genomic scale (known as the field of transcriptomics). This technology has already played an important role in understanding Bacterial Metabolism under a great variety of conditions, and in the improvement of numerous bacterial strains (70–74). However, the main contributions from the area of functional genomics are still to come and will result from the combined use of technologies that permit large-scale study of cell functioning and its interaction with the environment (i.e., combined analysis using genom-ic (DNA), transcriptomic (RNA), proteomic (protein), metabolomic (metabolites), and fluxomic (fluxes/enzymes) information). The era of functional genomics will contribute to an improved understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the relationships between microorganism and environment and in that way will establish the link between genotype and phenotype.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.