Biological Sciences

Reptiles

Reptiles are a class of vertebrates characterized by their scaly skin and cold-blooded nature. They include animals such as snakes, lizards, turtles, and crocodiles. Most reptiles lay eggs, although some give birth to live young. They are found in a wide range of habitats around the world and play important ecological roles as predators and prey.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

12 Key excerpts on "Reptiles"

- eBook - ePub

- Kristine Coleman, Steven J. Schapiro, Kristine Coleman, Steven J. Schapiro(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

23Behavioral Biology of Reptiles

Dale F. DeNardo Arizona State University CONTENTS Introduction Typical Participation in Research Behavioral Biology Natural History Ecology Sensing Their Environment Thermoregulation Social Organization and Behavior Parental Care Feeding Behavior Drinking Behavior Communication Common Captive Behaviors Normal Thermoregulation Feeding and Drinking Behavior Reproductive Behavior Abnormal Ways to Maintain Behavioral Health Captive Considerations to Promote Species-Typical Behavior Environment Social Groupings Feeding and Watering Strategies Training Special Situations Conclusions/Recommendations ReferencesIntroduction

Reptiles represent an immensely diverse group of organisms, with the major groups commonly referred to as the crocodilians, turtles, lizards, and snakes. As of April 2020, there were 11,242 species, and this number will surely be much higher by the time of publication, since this is 106 species more than were described as of December 2019 (Uetz et al., 2020). Phylogenetically, Reptiles are not a monophyletic group (i.e., a group that consists of all the descendants of a common ancestor). In fact, crocodilians, and even turtles, are more closely related to birds than they are to lizards and snakes (Crawford et al., 2014; Figure 23.1 ). Consequently, there is no identifying characteristic for Reptiles. Instead, they are best identified by a combination of what they have and do not have. In the simplest of terms, Reptiles are the amniotes that have an integument made of scales, but no feathers or hair.Given the phylogenetic diversity, Reptiles are also extremely diverse morphologically, ecologically, and behaviorally. Reptiles are distributed over most of the globe, with the exception of extremely high latitudes and elevations. They also occupy a diverse array of habitats, including oceans, deserts, tropics, temperate regions, and mountains. Within a given habitat, they fill a wide variety of niches, with microhabitats that are arboreal, terrestrial, aquatic, and fossorial. Their activity periods vary between diurnal, crepuscular, and nocturnal, sometimes within the same individual over the various seasons. Reptiles can be carnivorous, insectivorous, herbivorous, or omnivorous. - eBook - ePub

Companion Animal Care and Welfare

The UFAW Companion Animal Handbook

- James Yeates(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

18Reptiles (Reptilia)Joanna Hedley, Robert Johnson, and James Yeates18.1 History and Context

18.1.1 Common Natural History

Reptiles include more than 10 000 species, including turtles, tortoises, snakes, lizards, and crocodilians (Table 18.1 ). Reptiles are found on every continent except Antarctica and in a wide range of environments, including on land, in trees, in freshwater, and in seas, with some spending almost all their time in the water. Wild Reptiles are still caught for trade in many countries, in particular turtles and green iguanas (Praud and Moutou 2010 ), but the conservation status of many species is under threat (IUCN 2016 ).Examples of reptile species kept as companion animals.Table 18.1Crocodilians (Crocodilia) Snakes and lizards (Squamata) Tortoises, turtles and terrapins (Testudines) African dwarf crocodile(Osteolaemus tetraspis) Ball or Royal python (Python regius) Red‐eared sliders (Trachemys scripta elegans) Cuvier’s dwarf caiman (Paleosuchus palpebrosus) Boa constrictor (Boa constrictor) Mediterranean tortoises (Testudo spp.) Cornsnakes (Pantherophis guttatus) Bearded dragons (Pogona vitticeps) Green Iguanas (Iguana iguana) Leopard gecko (Eublepharis macularius) Yemen or veiled chameleon (Chamaeleo calyptratus) Most Reptiles depend almost entirely on their environment for warmth, and control their body temperature through their behaviour. They can lose heat via respiration, urination, and behaviours such as moving into the shade or water. They can maintain their temperature by burrowing or postural changes such as coiling up. They can gain heat from the sun and warm surfaces via radiation, conduction, and convection by altering their location, position, skin‐colour, and body posture and from digesting food in some species (e.g. South American rattlesnakes [Crotalus durissus terrificus], Tattersall et al. 2004 ). A few Reptiles (not usually kept as pets) can tolerate subzero temperatures through specific adaptations that either prevent or allow their body to cope with water freezing in their bodies (e.g. European common lizards [Lacerta vivipara]). Several species enter a period of dormancy or ‘brumation’, triggered by low temperatures and shortening day lengths, in which they are less active, less responsive and eat less (e.g. Box turtles [Terrapene spp.]), but others do not (e.g. Fijian crested iguanas [Brachylophus vitiensis - eBook - ePub

- Lynn C. Anderson, Glen Otto, Kathleen R. Pritchett-Corning, Mark T. Whary(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Chapter 19Biology and Diseases of Reptiles

Dorcas P. O’Rourke, DVM, MS, DACLAMa and Kvin Lertpiriyapong, DVM, PhDb ,a Department of Comparative Medicine, East Carolina University, The Brody School of Medicine, Moye Blvd, Greenville, NC, USA,b East Carolina University, The Brody School of Medicine, Moye Blvd, Greenville, NC, USASince their emergence 310–320 million years ago, Reptiles have evolved to be one of the most adaptive and remarkable groups of vertebrate animals on earth. Comprising over 9500 species, they can be found in diverse niches ranging from the arid Sahara desert to the tropical wetlands of the Amazon. Diverse reproductive physiologies and behaviors, along with adaptive characteristics such as parthenogenesis and development of venom glands for prey immobilization, make them attractive models for biomedical and basic biological research. This chapter provides information regarding biology, husbandry, and the diseases commonly affecting captive Reptiles most frequently used in research.Keywords

Reptile; Taxonomy; Biology; Husbandry; Nutrition; DiseasesOutlineI. Introduction 967A. .Taxonomy 967B. Use in Research 968C. Availability and Sources 969D. Laboratory Management and Husbandry 969II. Biology 974A. Anatomy and Physiology 974B. Nutrition 978C. Reproduction 980D. Behavior 981E. Physical Examination and Diagnostic Techniques 981III. Diseases 984A. Infectious Diseases 984B. Metabolic/Nutritional Diseases 1000C. Traumatic Disorders 1003D. Toxins 1005E. Neoplastic Diseases 1005References 1005I Introduction

Reptiles are the first group of vertebrates to evolve an amniotic, shelled egg, and thereby be freed of the requirement to reproduce in an aquatic environment. Like amphibians, Reptiles are ectothermic, and several lizard species superficially resemble salamanders. These morphologic and physiologic similarities led scientists to traditionally consider Reptiles and amphibians to be closely related. During the past two decades, however, emerging DNA technologies have allowed scientists to more accurately view genetic similarities, which resulted in major reclassification of these two groups, including realigning Reptiles more closely evolutionarily and genetically with birds. - eBook - ePub

Origins

The Search for Our Prehistoric Past

- Frank H. T. Rhodes(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Comstock Publishing Associates(Publisher)

9

The Reign of the Reptiles

What Is a Reptile?

We all know, of course. Or rather, we know one when we see one: scaly, slithering, snapping, sliding, cold-blooded, crawling creatures, and all the other uncomplimentary adjectives sometimes applied to them. Even the adjective reptilian , applied to human behavior, has the implication of a rather shady character. But Reptiles are wonderful creatures, the first major group to become adapted to life on the land. Their dry, scaly skin protects them against abrasion and loss of moisture; almost all of them reproduce by laying eggs on land, from which the young hatch as adults; they breathe by means of lungs, and they are cold-blooded; that is, they do not generate their own heat. And, though that cold-bloodedness tends to concentrate their distribution in temperate and tropical regions, it also means that they do not need to burn calories to regulate their body temperature.There are some 8,000 living species of Reptiles, descendants of a race that once ruled the Earth—land, sky, and seas—and it is from them that we—the mammals—ultimately developed.The Amniotic Egg

The secret of the Reptiles’ success has been the development of the amniotic egg. Just as the amphibians first established the transition from the water to the land, so also the development of the amniotic egg freed the Reptiles from the water-dependency of their amphibian forebears. The reptilian egg is internally fertilized and then laid on the land, enclosed in a protective shell, where it remains until the animal hatches at an advanced stage of development. Within the egg, the growing embryo is nourished by a large yolk enclosed in a fluid-filled sac, and it is also attached to the allantois, which disposes of waste products from the embryo, via the protective but porous shell.Figure 9.1. Structure of an amniote egg.(From Neil A. Campbell, Jane B. Reece, Martha R. Taylor, Eric J. Simon, and Jean L. Dickey, Biology: Concepts and Connections - eBook - PDF

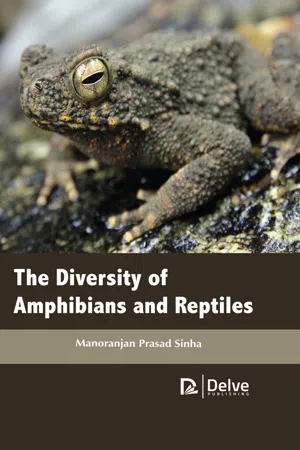

- Manoranjan Prasad Sinha(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Delve Publishing(Publisher)

• There is a lot of research that is being carried out on frogs as there are several chemical substances that are present on the skin The Diversity of Amphibians and Reptiles 6 of frogs which protect them from microbes and viruses because of which there is a lot of research on frogs to discover cure for several human diseases including AIDS and malaria. • Frogs are considered to be lucky and are cherished across several human cultures. 1.1.3. Reptiles Reptiles are animals with well-formed respiratory system with dry scaly skin. A majority of Reptiles live on the land whereas there are few groups that live in water. The meaning of the word Reptiles is that they are creepers who move stealthily in the darkness. Reptiles are mostly oviparous, which is egg laying animals, but there are some groups of Reptiles which are viviparous, which is giving birth to young ones. Some examples of animals that belong to Reptiles are snakes, Reptiles, crocodiles and turtles. Reptiles are known to be ectothermic animals and they have vertebra because of which they are called vertebrates. A majority of the Reptiles are terrestrial living organisms. There is one significant difference in the life cycle of Reptiles and amphibians, which is that Reptiles do not go any metamorphosis. There are several Reptiles that are identified until now and there are nearly 9000 species of Reptiles that are recorded. 1.1.4. Relationship between Amphibians and Reptiles Amphibians and Reptiles are known to be distantly related to one another and there are several similarities. Some of these similarities between amphibians and Reptiles are mentioned below: • The first major similarity between amphibians and Reptiles is that both these groups belong to phylum Chordata and subphylum Vertebrata. • The second major similarity among amphibians and Reptiles is that the animals belonging to both the groups are exothermic, cold-blooded animals. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Academic Studio(Publisher)

________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Chapter- 5 Reptiles Reptiles Temporal range: Mississippian - Recent 320–0 Ma Clockwise from above left: Spectacled Caiman ( Caiman crocodilus ), Green Sea Turtle ( Chelonia mydas ), Tuatara ( Sphenodon punctatus ) and East ern Diamondback Rattlesnake ( Crotalus adamanteus ). Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Superclass: Tetrapoda (unranked): Reptiliomorpha ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ (unranked): Amniota Class: Reptilia Laurenti, 1768 Subgroups • Anapsida (=Parareptilia?) o Testudines (traditional) • Eureptilia o Crocodilia o Sphenodontia o Squamata o Testudines (molecular) Reptiles are animals in the (Linnaean) class Reptilia. They are characterized by breathing air, laying shelled eggs, and having skin covered in scales and/or scutes. Reptiles are classically viewed as having a cold-blooded metabolism. They are tetrapods (either having four limbs or being descended from four-limbed ancestors). Modern Reptiles inha-bit every continent with the exception of Antarctica, and four living orders are currently recognized: • Crocodilia (crocodiles, gavials, caimans, and alligators): 23 species • Sphenodontia (tuataras from New Zealand): 2 species • Squamata (lizards, snakes, and worm lizards): approximately 7,900 species • Testudines (turtles and tortoises): approximately 300 species Contrary to amphibians, Reptiles do not have an aquatic larval stage. As a rule, Reptiles are oviparous (egg-laying), although certain species of squamates are capable of giving live birth. This is achieved by either ovoviviparity (egg retention) or viviparity (birth of offspring without the development of calcified eggs). Many of the viviparous species feed their fetuses through various forms of placenta analogous to those of mammals, with some providing initial care for their hatchlings. - eBook - PDF

Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California

Revised Edition

- Robert C. Stebbins, Samuel M. McGinnis(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

Reptiles 218 R E P T I L E S Taxonomy, Anatomy, Physiology, and Behavior of Reptiles In our introduction to the amphibians we highlighted the landmark stage in vertebrate evolution some 400 million years ago, when a group of shal-low-water fishes acquired anatomical and behavioral features that enabled them to explore shoreline habitats and ultimately give rise to the first tet-rapod vertebrates. In contrast to this scenario, the evolution of Reptiles from what was most likely a common ancestral form for both Reptiles and amphibians entailed no such dynamic transformation but instead pro-gressed as a gradual accumulation of features that allowed many members of this new group of terrestrial vertebrates to no longer be dependent on aquatic habitats for any phase of their life history. One cannot begin a discussion of the class Reptilia without recall-ing that this was the first truly dominant group of terrestrial vertebrates. This dominance is most evident in the paleo–natural history of the Archosauria. Except for the descendants of one order (Crocodilia), all other major groups within this group are extinct. Even so, many species of the group collectively referred to as dinosaurs are well known because of their starring roles in films and books, most of which feature large car-nivorous species. However, it was the many, less popularized herbivorous forms that provided a wide, primary consumer base for the flesh-eating secondary consumers, thus establishing an intraclass food web that has been duplicated only once since by the mammals. The “Age of Reptiles” lasted for some 183 million years, whereas the “Age of Mammals” is only about 65 million years young. Of the approximately 20 currently recognized orders of Reptiles, only four are represented by living species, which at this writing number about 8,240. The smallest of these is the Rhynchocephalia, which contains only two surviving species, the tuataras (genus Sphenodon ). - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Research World(Publisher)

________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Chapter- 5 Reptiles Reptiles Temporal range: Mississippian - Recent 320–0 Ma Clockwise from above left: Spectacled Caiman ( Caiman crocodilus ), Green Sea Turtle ( Chelonia mydas ), Tuatara ( Sphenodon punctatus ) and Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake ( Crotalus adamanteus ). Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Superclass: Tetrapoda (unranked): Reptiliomorpha ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ (unranked): Amniota Class: Reptilia Laurenti, 1768 Subgroups • Anapsida (=Parareptilia?) o Testudines (traditional) • Eureptilia o Crocodilia o Sphenodontia o Squamata o Testudines (molecular) Reptiles are animals in the (Linnaean) class Reptilia. They are characterized by breathing air, laying shelled eggs, and having skin covered in scales and/or scutes. Reptiles are classically viewed as having a cold-blooded metabolism. They are tetrapods (either having four limbs or being descended from four-limbed ancestors). Modern Reptiles inhabit every continent with the exception of Antarctica, and four living orders are currently recognized: • Crocodilia (crocodiles, gavials, caimans, and alligators): 23 species • Sphenodontia (tuataras from New Zealand): 2 species • Squamata (lizards, snakes, and worm lizards): approximately 7,900 species • Testudines (turtles and tortoises): approximately 300 species Contrary to amphibians, Reptiles do not have an aquatic larval stage. As a rule, Reptiles are oviparous (egg-laying), although certain species of squamates are capable of giving live birth. This is achieved by either ovoviviparity (egg retention) or viviparity (birth of offspring without the development of calcified eggs). Many of the viviparous species feed their fetuses through various forms of placenta analogous to those of mammals, with some providing initial care for their hatchlings. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Research World(Publisher)

________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Chapter- 1 Reptile Reptiles Temporal range: Mississippian - Recent 320–0 Ma Clockwise from above left: Spectacled Caiman ( Caiman crocodilus ), Green Sea Turtle ( Chelonia mydas ), Tuatara ( Sphenodon punctatus ) and Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake ( Crotalus adamanteus ). Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Superclass: Tetrapoda (unranked): Reptiliomorpha (unranked): Amniota Class: Reptilia Laurenti, 1768 Subgroups ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ • Anapsida (=Parareptilia?) o Testudines (traditional) • Eureptilia o Crocodilia o Sphenodontia o Squamata o Testudines (molecular) Reptiles are animals in the (Linnaean) class Reptilia. They are characterized by breathing air, laying shelled eggs, and having skin covered in scales and/or scutes. Reptiles are classically viewed as having a cold-blooded metabolism. They are tetrapods (either having four limbs or being descended from four-limbed ancestors). Modern Reptiles inhabit every continent with the exception of Antarctica, and four living orders are currently recognized: • Crocodilia (crocodiles, gavials, caimans, and alligators): 23 species • Sphenodontia (tuataras from New Zealand): 2 species • Squamata (lizards, snakes, and worm lizards): approximately 7,900 species • Testudines (turtles and tortoises): approximately 300 species Contrary to amphibians, Reptiles do not have an aquatic larval stage. As a rule, Reptiles are oviparous (egg-laying), although certain species of squamates are capable of giving live birth. This is achieved by either ovoviviparity (egg retention) or viviparity (birth of offspring without the development of calcified eggs). Many of the viviparous species feed their fetuses through various forms of placenta analogous to those of mammals, with some providing initial care for their hatchlings. - eBook - PDF

The Amphibians and Reptiles of Alberta

A Field Guide and Primer of Boreal Herpetology

- A. P. Russell, Aaron M. Bauer, Irene McKinnon(Authors)

- 2000(Publication Date)

- University of Calgary Press(Publisher)

Ultimately, most amphibians rely on a source of water for repro-duction and larval existence. Such constraints have circumscribed the habitats and ecological niches available to amphibians. The CHARACTERIZATION OF AMPHIBIANS AND Reptiles 13 strategies employed by amphibians to deal with the problems posed by the environment will form the basis for portions of the second part of this book. Reptiles, which arose from an amphibian stock (Fig. 2.1), have escaped from many of the constraints acting upon living lissamphibians by way of two major innovations: a desiccation-resistant keratinized skin, and a shelled egg that permits direct development on land. Reptiles are therefore much more terrestrial than amphibians, and their distribution is not so closely related to the availability of free water. Reptiles first appeared in the Carboniferous Period (about 330 million years ago) and radiated in the Permian period and through-out the Mesozoic Era. The latter is commonly known as the Age of Reptiles and is testimony to their apparent dominance in ter-restrial situations during this time. Most conspicuous were the vari-ous groups collectively known as the dinosaurs. Until their sudden demise at the end of the Cretaceous Period (about 65 million years ago), the dinosaurs were the major large herbivores and carnivores throughout most of the world. The dinosaurs were representatives of a large group of Reptiles known as the archosauromorphs. Other members of this lineage include the crocodylians, which still sur-vive, and the flying pterosaurs. Birds too are archosauromorphs and, in fact, are the living legacy of the dinosaurs, current ortho-doxy suggesting that they are their direct descendants. The archosauromorphs are one major branch of a group of rep-tiles known as diapsids (= two arches) because of the configuration of bones on the side of the skull, behind the eye. The other major diapsid lineage is the Lepidosauromorpha. - Varga, Molly, Lumbis, Rachel, Gott, Lucy, Varga, Molly, Lumbis, Rachel, Gott, Lucy(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- British Small Animal Veterinary Association(Publisher)

Taxonomy The three main reptilian orders (and sub-orders) are: ■ Squamata – Sauria (lizards) – Serpentes (snakes) ■ Chelonia (tortoises, turtles, terrapins) ■ Crocodilia (alligators, crocodiles). Each species has a scientific name that is specific to that individual species; for example, Python regius is the royal python. It is important to be aware that own-ers will sometimes present their animals with both a common name and the species’ scientific name; this is especially important where a species has multiple common names, e.g. the royal python is also known as the ball python but is always Python regius . Anatomy and physiology Nursing the reptilian patient requires an understand-ing of the animal’s intimate physiological processes. The veterinary nurse should have an understanding of the general anatomical and physiological differ-ences between Reptiles and other vertebrates, as well as the differences between reptilian taxonomic groups (Figure 4.3). With over 9000 species of reptile, there are many anatomical and physiological adap-tations to specific environments, with different feed-ing techniques employed; these species-specific differences are beyond the scope of this chapter. Readers are advised to research individual species as they are presented. Musculoskeletal system and dentistry Lizards, chelonians and crocodilians are generally more similar to mammals in their skeletal anatomy than snakes are. Snakes have ribs attached to all ver-tebrae apart from the coccygeal vertebrae. Ventrally, the coccygeal vertebrae contain the coccygeal artery and vein, and this is a common site for venepuncture 87 Chapter 4 Reptiles: biology and husbandry (continued) (b) Snake anatomy.- Diane Schmidt(Author)

- 2003(Publication Date)

- Libraries Unlimited(Publisher)

The amount of information on each species varies, but generally includes synonymy, diagnosis, description, range, and remarks. There are often several photographs or drawings of preserved specimens, including X rays. Reptiles Gans, Carl, ed. Biology of the Reptilia. New York: Academic Press, 1969-98. 19 vol. Price varies. Each volume in this classic treatise covers a particular topic such as morphology or physiology. The articles are designed to summarize the state of knowledge in reptilian biology and contain numerous illustrations and extensive references. Volume 1 contains a chapter discussing the ori- gin of Reptiles, but all other chapters deal with living Reptiles rather than fossils. Later volumes were published by Wiley, Liss, the University of Chicago Press, and the Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. Turtles Alderton, David. Turtles and Tortoises of the World. New York: Facts on File, 1988. 191 p. $32.95. ISBN 0816017336. One of the several excellent Facts on File encyclopedias, this one cov- ers the biology and classification of chelonians around the world. The author provides extensive background information on interactions with humans, anatomy, reproduction, and evolution of turtles. This introductory section is followed by descriptions of each turtle family. There are distri- bution maps and color photographs of representative species as well as text discussing the natural history, range, and descriptions of family mem- bers. An appendix provides a systematic list of turtle species, including English common names. 236 Guide to Reference and Information Sources in the Zoological Sciences Ashley, Laurence M., and Carl Petterson. Laboratory Anatomy of the Turtle. Dubuque, IA: W.C. Brown, 1962. 48 leaves. (Laboratory Anatomy series). $39.06. ISBN 06970460IX. A dissection manual for a generalized turtle (species not defined). Ernst, Carl H., R. G. M. Altenburg, and Roger William Barbour.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.