Economics

Oil Crisis 1973

The 1973 oil crisis was a major event in which the members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) imposed an oil embargo on the United States and other countries that supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War. This led to a significant increase in oil prices and had a profound impact on the global economy, causing widespread inflation and energy shortages.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Oil Crisis 1973"

- eBook - ePub

US Foreign Policy in the Middle East

From Crises to Change

- Yakub Halabi(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Chapter 4The Oil Embargo Crisis in 1973–1974Introduction: Defining the Problem

On the eve of the October War (also called the Yom Kippur War) of 1973, US policy toward the Middle East was based on several ideas. Arms exports to the region should be limited. Iran should be empowered with advanced American weapons so that it would be able to play the role of a regional policeman. The US should stay out of the Arab–Israeli peace process. Finally, the US should do all in its power to limit the influence of the Soviet Union in the area. With the eruption of the oil crisis, some of these ideas would rapidly become obsolete.As never before in the course of the Cold War, the Arab Oil Embargo of 1973–74 shook the foundations of the Western alliance. For the first time, members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) managed to exploit their power as major oil suppliers (Levy 1974; Quandt 1981; Safran 1985; Sampson 1975).The crisis took the Western world by surprise. For many years, it had been accustomed to inexpensive oil and it was unprepared for a sharp rise in oil prices. During the embargo, the price of an oil barrel nearly quadrupled within three months to almost $12. In the words of Henry Kissinger, ‘the oil price shock caused a deadly combination of severe recession and high inflation which, in the United States, reached 14 percent a year at its height. The energy crisis was even more disastrous for the non-oil producing nations of the developing world’ (Kissinger 1999, 664).Furthermore, the transfer of capital from developed countries to oil-producing countries created a trade deficit for the former of $40 billion at current prices. ‘[M]uch of the world’s wealth had suddenly shifted to an obscure corner of the world’ (Sampson 1975, 343). In the same vein, Walter Levy warned the West that ‘the supply of oil from individual producing countries or a group of them to individual consuming countries or a group of them might … at a time unknown, again be curtailed or completely cut off for a variety of economic, political, strategic or other reasons’ (Levy 1974, 691). - eBook - ePub

- Fiona Venn(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Chapter 3 , was both more even-handed in its dealings with the respective belligerents than was expected by the Israeli Prime Minister, Golda Meir, and was also a startling departure from normal practice in the ‘hands-on’ approach adopted by the Secretary of State, which entailed spending long periods of time out of the United States. By the end of 1973, the main part of the crisis was over, although peace in the Middle East was still precarious, and the consuming nations were reeling at the likely impact of a fourfold increase in the price of oil in only three months. OPEC and OAPEC had both contributed to the cause of that increase: OAPEC through its boycott, as opposed to the oil price decisions which remained entirely within OPEC’s jurisdiction. In the discussions on the appropriate price level for oil, particularly in the December 1973 OPEC meeting that agreed on a new official price of over 11 dollars per barrel, one of the leading hawks was the Shah of Iran, leader of a non-Arab state which at that time provided Israel with the majority of its oil needs. The country taking the lead in implementing the oil boycott, Saudi Arabia, pressed for moderation on price, and argued forcibly against setting an official price close to the highest spot market levels. However, this potent combination – a Middle Eastern crisis and a feeling on the part of the oil producers that a price rise was appropriate and overdue – also coincided in the second major oil crisis of the decade in 1978–9.The second oil crisis: 1979

The gloomy prognostications of many commentators in the immediate aftermath of 1973 proved to be erroneous.41 Although the cash price of petroleum remained high, the escalating rates of inflation in the industrialized world eroded its impact upon their economies, while increasing the prices of manufactured goods to the developing world (including the members of OPEC). While the position of oil companies in the international oil industry had been affected by the unilateral decision by OPEC to take total control of oil price and production levels, changes had already been in train before 1973, and in many respects the shift towards a more managerial and technical role reduced political pressures upon the companies, while doing little to affect their profit levels. By the end of the 1970s, therefore, there was a real sense within the industrialized West that the worst of the oil crisis had definitely passed. However, towards the end of the decade, the international atmosphere once again became one of crisis, and yet again events in the Middle East, coupled with the desire of the oil producers to secure an increase in the real price of their oil, were to produce a dramatic and rapid increase in oil prices, and catapult the energy crisis back on to the international agenda.As in 1973, a number of different factors contributed to the genesis of the crisis. Of these trends, perhaps the most striking initially was the escalation of tension within the Cold War. The early 1970s had witnessed a slackening of some Cold War tensions, encouraged by the Nixon Administration, which had made friendly overtures towards the Soviet Union and China and encouraged détente - eBook - PDF

Energy Security

The External Legal Relations of the European Union with Major Oil and Gas Supplying Countries

- Sanam S. Haghighi(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Hart Publishing(Publisher)

However, the differences among Member States’ strategies to guarantee this security created barriers to reaching a common policy as desired by the Commission. The next decade and the occurrence of the disastrous oil crisis of 1973 confirmed that in order to reach a common position on energy, there was still a long and arduous way to go. 2.4. THE OIL CRISIS AND THE NEW PHASE OF ENERGY POLICY: 1973–1986 On 6 October 1973, Egypt and Syria declared their aim of recapturing the Arab territories occupied by Israel since 1967. Following this event, the Arab Oil Exporting Countries threatened to cut their production of oil by 5 per cent and to continue to reduce that amount thereafter, until Israel withdrew from the occupied Arab lands. Saudi Arabia pressured the US to change its policy towards Israel and declared that Aramco’s exports (the major Saudi Arabian oil company) would be halted if no change in their policy took place. The United States, having the weak repercussions of the 1967 crisis in mind, did not take this threat seriously and thought of the use of the ‘oil weapon’ by Saudi Arabia as having no more effect than in 1967. 68 Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, sought to ensure that the non-Arab productive capacity would not undermine the embargo and also 67 See generally, ibid at pp 8–10. 68 Evans, OPEC and Its Member States , above n 58, at 84. An ‘oil weapon’ signifies ‘any manipulation of price and/or supply of oil by exporting nations with the intention of changing the The Oil Crisis and the New Phase of Energy Policy: 1973–1986 53 supervised the destination embargo more closely 69 to prevent the swap arrange-ments, which had been used during the 1967 crisis to undermine the boycott. 70 Exporting countries, worried about the negative effects of the embargo on their revenue, increased the tax on oil, which enabled production to be cut without causing the revenue to fall below the revenue of the previous month. - No longer available |Learn more

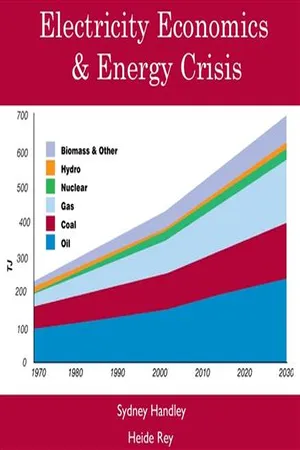

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Academic Studio(Publisher)

____________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ____________________ Chapter- 9 1973 Oil Crisis 1973 oil crisis Other names Arab Oil Embargo Date October 1973 - March 1974 The 1973 oil crisis started in October 1973, when the members of Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries or the OAPEC (consisting of the Arab members of OPEC, plus Egypt, Syria and Tunisia) proclaimed an oil embargo in response to the U.S. decision to re-supply the Israeli military during the Yom Kippur war; it lasted until March 1974. With the US actions seen as initiating the oil embargo and the long term possibility of high oil prices, disrupted supply and recession, a strong rift was created within NATO. Additionally, some European nations and Japan sought to disassociate themselves from the US Middle East policy. Arab oil producers had also linked the end of the embargo with successful US efforts to create peace in the Middle East, which complicated the situation. To address these developments, the Nixon Administration began parallel negotiations with both Arab oil producers to end the embargo, and with Egypt, Syria, and Israel to arrange an Israeli pull back from the Sinai and the Golan Heights after the fighting stopped. By January 18, 1974, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had negotiated an Israeli troop withdrawal from parts of the Sinai. The promise of a negotiated settlement between Israel and Syria was sufficient to convince Arab oil producers to lift the embargo in March 1974. By May, Israel agreed to withdraw from the Golan Heights. Independently, the OPEC members agreed to use their leverage over the world price setting mechanism for oil to stabilize their real incomes by raising world oil prices. This action followed several years of steep income declines after the recent failure of negotiations with the major Western oil companies earlier in the month. For the most part, industrialized economies relied on crude oil, and OPEC was their predominant supplier. - eBook - PDF

- ISEAS(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- ISEAS Publishing(Publisher)

SOUTHEAST ASIA AND THE WORLD OIL CRISIS: 1973 Robert F. Ichord, Jr. The year 1973 saw the dramatic emergence of a full-fledged world oil crisis and the almost hopeless entanglement of oil issues with larger aspects of world politics. To some extent, the fourfold price increases by OPEC, the production cutbacks by most Arab producers, and the Arab oil embargo represented merely a rapid acceleration of existing trends in the international oil world. Yet by the year's end, it appeared that the political, economic and military impact of these events was leading to what one oilman termed The New World. For Southeast Asia, which was already in the midst of substantial readjustment in its external relations following the Vietnam ceasefire and the start of the American military withdrawal, the events of Octobe · i;-, 7 November and December seemed capable of generating important changes in the structures of interaction with major powers. This article takes a brief look at the impact of the world oil crisis on the domestic and international political economy of Southeast Asia and suggests some prospects for the future. I . Oil Import Dependence and the Structure of the Oil Industry in Southeast Asia A central fact about Southeast Asia's position in the world oil crisis is its high dependence on Middle East oil imports supplied by the major international oil companies, principally Exxon, Shell, Caltex, Mobil and British Petroleum (BP), for its energy. Even the principal oil producing nations in the region, Indonesia and Malaysia, satisfy their domestic needs through imports from the Middle East, while exporting their low-sulphur oil to Japan and the United States at premium prices.* By establishing refining and marketing operations in Southeast Asia, the major oil companies have developed captive markets for their Middle East crude oil * Prices of Indonesian and Malaysian crude are about US$2.00 t;:er barrel nore than Persian Gulf discount prices. - eBook - ePub

The Age of Global Economic Crises

(1929-2022)

- Juan Manuel Matés-Barco, María Vázquez-Fariñas, Juan Manuel Matés-Barco, María Vázquez-Fariñas(Authors)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

3 Major economic recessions in the last quarter of the 20th century The oil crisis (1973–1980)María Vázquez-FariñasDOI: 10.4324/9781003388128-33.1 Introduction

Energy is one of the main drivers of economic growth, and oil has been considered a key energy resource since the advent of the second industrial revolution. Its consumption grew at an extraordinary rate throughout the 20th century, increasing the dependence of the most industrialised countries on this resource. In this context, the arrival of an oil crisis in the last third of the century and the strong interconnection of the oil market with other markets would significantly affect economic activities across the globe.The last third of the 20th century was a transformative period in the world economy. In the 1970s, following the collapse of the Bretton Woods international monetary system and the problems arising from the oil crisis, globalisation took on new forms and posed fresh challenges, resulting in a new global economic environment characterised primarily by high inflation and low growth in Western Europe. During this time there was a noticeable shift toward more market-oriented policies, although it was not until well into the 1980s that economic growth recovered (Warlouzet 2017, 1–2).This chapter will therefore examine the last great economic recession of the 20th century, known as the oil crisis or the oil crash. Its analysis is approached in three large blocks, into which the different sections are fitted. In the first, after this introduction, the general framework of the world economy toward the middle of the 20th century is presented. The second section analyses in detail the background and causes of the crisis, its immediate effects, the main consequences, in both developed and undeveloped countries, and, finally, the measures adopted to bring an end to the recession. The third section examines the re-emergence of the crisis in 1979, analysing the measures adopted by the main powers to overcome this situation. The chapter closes with some conclusions about the period analysed. - eBook - ePub

- Ragaei el Mallakh(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

At the time this paper was completed in June 1980, it seemed possible, if not likely, that Iran’s turbulent policy would be upset again in conflict with the United States or Iraq. However, there was not much more that sanctions or even a blockade could do to Iranian oil exports by then. The exports were already down to perhaps less than 1 million barrels per day (b/d), compared with 5 million b/d in mid-1978. The surplus of supply potentially available elsewhere over effective demand in the crude oil market of spring 1980 was probably two or three times as large as the remaining Iranian exports that might be cut off from the market. So the effects of a renewed crisis there upon the market might be considered very limited in strictly economic terms. Politically, however, a renewed Iranian crisis was still liable to affect the market by contributing yet again to all buyers’ anxiety and some sellers’ self-confidence.Profiles of CrisisIn the amplitude of their effects upon OPEC and world crude production, the two crises were notably similar. Indeed, it is difficult to separate them on a single graph because the fluctuations in supply that they wrought happened at roughly the same level of OPEC production. Even the timing was only a couple of months out of phase. The decline in OPEC output from November 1978 to January 1979 — from a strike in the Iranian oilfields to a shutdown as the revolution erupted — was never quite as sharp or as deep as from September to November 1973, during the Arab oil embargo. (Production in autumn 1978 had never been quite as high as in autumn 1973, however.) In both periods, it took about six months for OPEC production to regain its pre-crisis level, but in 1979, world production took only about three months to recover. There was more non-OPEC supply available to fill in the gap in production. A comparison such as that in figure 1 is a reminder that while OPEC output in 1978–1980 was only at the same general level as in 1973–1975, world output had increased. Since that earlier crisis, there has been slow but substantial growth in world oil production: in net terms, all of it has been outside OPEC.The political crisis affecting Middle East crude supplies dragged on much longer in 1979 than in 1973. As noted above, the pressure on supplies did not. In both cases the initial upsurge of prices reflected the understandable fear of importers that the crisis might reduce world crude supply sharply for a significant period, but in neither case did that happen. Both crises are almost lost in annual statistics. Following the Arab embargo, OPEC production in 1974 averaged less than 1 percent lower than in 1973, and world production of crude was virtually unchanged (admittedly, in the few years before, OPEC exports, particularly of Arab crude, had been rising rapidly). In 1979, even OPEC production turned out to be higher than in 1978, in spite of Iran’s brief shutdown and prolonged reduction of exports, and world production reached a record 62.8 million b/d. But the expectations — and, perhaps even more, the fears of political uncertainty — were what mattered. - eBook - PDF

Mismanaging Mayhem

How Washington Responds to Crisis

- James Jay Carafano, Richard Weitz, James Jay Carafano, Richard Weitz(Authors)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

At the same time, it was a decade when world events roiled oil markets and the U.S. economy. Burgeoning domestic demand for oil outstripped domestic supply. Consequently, oil imports grew significantly over the course of the decade. Though imports per se are not a problem, especially with a fungible good like petroleum, a significant amount came from Middle East regimes that proved to be unstable and/or unfriendly throughout the decade. Complicating 6 Chapter Crisis! What Crisis?: America’s Response to the Energy Crisis Ben Lieberman matters further, these oil-producing nations were not acting individually, but had effectively organized themselves into another 1970s icon, the OPEC oil cartel. There were two oil shocks — one sparked by the Arab oil embargo of 1973 – 74 following the Yom Kippur War, and the other by the Iranian Revolution of 1978 – 79. The so-called “energy crisis,” periodic fuel shortages, gas lines, rationing, and price increases — as well as energy-related damage to the overall economy — are among the unpleasant memories from that era. But however serious the global turmoil was at the time, it is a mistake to blame America’s energy ills of the 1970s entirely on these exogenous forces. At almost every turn, Washington took an already challenging energy situation and made it worse through its own policy blunders. The federal government’s newly created maze of economic and environmental regulations, and the agen- cies tasked with implementing them, greatly hampered domestic energy sup- plies and limited the ability to respond to events. In retrospect, government interagency policies contributed to the harm at least as much as any foreign entity. The errors of the 1970s should serve as a cautionary tale as America again faces similar challenges. Many challenges faced by the interagency team may have national security implications. - eBook - PDF

Black Gold

Britain and Oil in the Twentieth Century

- Charles More(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Continuum(Publisher)

7 Crisis: Oil in the 1970s PRELUDE TO CRISIS On 21 October 1973 the chairmen of Shell and BP, Frank McFadzean and Sir Eric Drake, met Edward Heath, the Prime Minister, at Chequers, his official residence. The world was in crisis, and one of the roots of that crisis was oil. Following another Arab-Israeli war, the Arab states were both cutting production, and totally embargoing oil supplies to the USA and the Netherlands. At the same time Middle Eastern oil prices were rising at an unprecedented rate. They had already reached $5 per barrel – more than two and a half times the level at the beginning of 1970. Britain herself was suffering increasing inflation and faced the possibility of industrial action by coalminers – domestically mined coal still being used extensively in power generation. 1 Unlike 1967, Britain was not on the Arab embargo list, although all importing countries were threatened by cuts which would reduce production by 5 per cent each month. But as in 1967, the oil companies tried to deal with the situation by adjusting supplies from non-Arab producers, so spreading the cuts evenly. Whereas in 1967, however, there had been plenty of oil to go round and ‘shut-in’ US production to add to the supply, in 1973 world supplies were desperately tight and the US was producing to its limit. Spreading the cuts meant pain for everybody. Heath had invited McFadzean and Drake to Chequers to ask them not to spread the cuts but to allocate Britain all its normal supply of oil since it was not one of the embargo targets. 2 The request was on the face of it understandable. But if acted upon it would open a hornet’s nest of problems. Britain had benefited in 1956 and 1967 because oil companies had reallocated supplies to even out shortages. Now Heath, who had taken Britain into the European Community, wanted them to - eBook - PDF

Inside Japanese Business: A Narrative History 1960-2000

A Narrative History 1960-2000

- Makota Ohtsu, Tomio Imanari(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Part 111 Period between Two Oil Crises: APeriod of Change (1974-1980) This page intentionally left blank 9 General Environment, 1974-80 During this period (1974-80) the basic framework of international politics remained the same as in the previous period. The cold war between the free-world nations and the Communist-bloc nations continued, although it seemed that both the Soviet Union and Communist China attempted to ease tensions with the United States, while the relationship between Russia and China continued to be strained. A new destabilizing element in international politics was the emergence of Islamic nations equipped with oil money and Islamic religious fervor. The declining power of Shah Pahlavi of Iran was the most disturbing devel-opment for the United States and its allies, because a pro--United States Iran had been an important pillar ofU.S. strategy for the Middle East (Ministry of Foreign Affairs 1979: 153). The political destabilization in the region was particularly disturbing to Japan, which heavily depended on the region for its oil supply. In order to deal with the oil crisis, in February 1974, the U.S. government took the initiative in holding international meetings of oil-consuming na-tions, meetings attended by the foreign ministers and finance ministers of thirteen nations: the United States, Canada, Norway, Japan, and nine (EC) member nations (Ministry of Foreign Affairs 1974: 68,69). At the meetings the United States advocated the creation of an organization of oil-consuming nations that would work as a countervailing force against the OPEC interna-tional cartel. It was proposed that this organization would directly negotiate with OPEC on behalf of member nations so that they could consolidate their bargaining powers. This praposal did not gain acceptance because of astrang objection by 131 - eBook - PDF

Britain and the Arab Gulf after Empire

Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates, 1971-1981

- Simon C. Smith(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

91 Telegram from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office to Washington, No, 1269, 15 June 1973, cited in ibid., document 127. 92 James Bamberg, British Petroleum and Global Oil, 1950–1975: The Challenge of Nationalism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 474. 93 Alexei Vassiliev, King Faisal of Saudi Arabia: Personality, Faith and Times (Lon-don: Saqi Books, 2012), p. 376. 94 Jordan J. Paust and Albert P. Blaustein, The Arab Oil Weapon (New York: Oceana Publications, 1977), p. 43. 95 Bamberg, British Petroleum and Global Oil, 1950–1975 , p. 477. 96 Paust and Blaustein, The Arab Oil Weapon , p. 45. 97 Francesco Petrini, ‘Eight squeezed sisters: The oil majors and the coming of the 1973 oil crisis’, in Elisabetta Bini, Giuliano Garavini, and Frederico Romero (eds.), Oil Shock: The 1973 Crisis and its Economic Legacy (London and New York: I. B. Tau-ris, 2016), p. 89. 98 ‘Our objectives in the Middle East’, Minute by Parsons, 11 October 1973, cited in Hamilton and Salmon, The Year of Europe , document 259. 99 Report on oil by policy for Cabinet Ministerial Committee on energy strategy, 8 Feb-ruary 1993, ibid., document 23. 100 ‘Oil’, Minute by Hunt, 9 October 1973, PREM 15/1837. 101 Telegram from FCO to Jedda, No. 345, 12 October 1973, cited in Hamilton and Salmon, The Year of Europe , document 268. 102 Telegram from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office to Washington, no. 2081, 15 October 1973, cited in Hamilton and Salmon, The Year of Europe , document 288. 103 Ibid. The oil revolution, 1973 69 104 David Wood, ‘Mr Heath is determined not to antagonize Arab oil suppliers’, Times , 6 November 1973, http://find.galegroup.com/ttda/infomark.do?&source=g ale&prodId=TTDA&userGroupName=unihull&tabID=T003&docPage=article&s earchType=AdvancedSearchForm&docId=CS17135974&type=multipage&conten -tSet=LTO&version=1.0 [accessed 5 December 2016]. 105 Telegram from Henderson to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, No.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.