History

Appeasement

Appeasement refers to the diplomatic strategy of making concessions to an aggressive power in order to avoid conflict. It gained prominence in the 1930s as European powers sought to appease Nazi Germany's expansionist ambitions. The policy is often criticized for failing to prevent World War II and allowing Hitler to strengthen his position.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Appeasement"

- eBook - ePub

Britain in Global Politics Volume 1

From Gladstone to Churchill

- C. Baxter, M. Dockrill, K. Hamilton, C. Baxter, M. Dockrill, K. Hamilton(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

1 It occurred, first, in relation to Western Europe and the security of the home islands and, then, as the expanding British Empire saw policy-makers in London defend the manifold interests of the only world Power, in key areas of the globe. Thus, Appeasement had been just one of a number of tactical alternatives in the planning and execution of British foreign policy designed to ensure the security of Britain’s national and Imperial interests. These alternatives also included working with other Powers politically or militarily in short-term arrangements or longer-term alliances, unilateral threats or the use of military action, a reliance on conference diplomacy, and more. However, after mid-1937, because of his perception that pursuing the balance of power in Europe and the Far East held danger – flowing from his belief that failure to maintain the balance had led to the Great War of 1914–1918 – Chamberlain used his position as premier to change the strategic basis of British foreign policy. In one sense, it amounted to a coldly realistic decision, reflecting the political strictures placed on British governments in the 1930s by both the electorate that wanted to avoid war and the need to buy time to allow for rearmament. In another, so Chamberlain and his supporters argued, it would bring long-term stability to Europe by meeting legitimate German territorial grievances without Berlin resorting to armed conflict to resolve them.Appeasement as a British foreign policy precept is a somewhat amorphous concept that changed over time and was modified by circumstance. With a historian’s lens, Paul Kennedy defined it in 1976 as ‘the policy of settling international (or, for that matter, domestic) quarrels by admitting and satisfying grievances through rational negotiation and compromise, thereby avoiding the resort to an armed conflict which would be expensive, bloody, and possibly very dangerous’.2 But a range of British leaders in the past possessed subtly different views. William Ewart Gladstone, four times prime minister between 1868 and 1894, talked about seeking ‘the concord and hearty co-operation’ amongst Great Powers to establish international stability – in this case, although pathologically Russophobic, Gladstone referred to Anglo-Russian relations and the ‘Eastern Question’ after the 1878 Congress of Berlin.3 Later, before the Great War in relation to the German question, Sir Edward Grey, the Liberal foreign secretary, spoke about ‘mutual advantage & increased security’.4 - eBook - ePub

- Stephen R. Rock(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- The University Press of Kentucky(Publisher)

Whether concessions are perceived as indicating an opportunity for advancing further demands or committing further acts of aggression also depends on certain other factors, including the potential costs associated with such activities at several different levels. Simply stated, Appeasement is less likely to elicit further demands or to promote further aggression in cases where the recipient of concessions has strong reasons to remain on cordial terms with the appeasing state. While these incentives may not be sufficient to cause the target state to abandon its most important objectives, they may, once these objectives have been met, dissuade it from aggressively pursuing additional aims to which it is less committed.LESSONS FOR POLICYMAKERSOne of the purposes of this study is to provide guidance for policymakers contemplating a policy of Appeasement vis-à-vis a particular adversary. Beyond the propositions elaborated above, the cases suggest a few basic lessons. Most of these fall into the category of common sense, but given the failure to observe certain of them in previous situations, perhaps they bear repeating here.1. Know your adversary. This is by far the most important lesson. Unless one understands an opponent and his motives, one cannot know the prospects for successful Appeasement or how to devise an appropriate strategy. Failure to understand adequately the target state and its leaders contributed significantly to failed Appeasement in several cases, including British efforts to conciliate Nazi Germany and American attempts to improve relations with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq.2. Reevaluate policy on a regular basis. Because a target state’s motives are typically complicated and obscure, policymakers often will not be able to know their adversary as fully as they would like. A policy of Appeasement, like any other policy, should be adopted provisionally, and its effectiveness evaluated regularly.3. Devise tests - eBook - ePub

From the Treaty of Versailles to the Treaty of Maastricht

Conflict, Carnage And Cooperation In Europe, 1918 – 1993

- Martin Holmes(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

6Chamberlain, Churchill and the Appeasement debate

DOI: 10.4324/9781003260998-7Many scholars have argued that Appeasement was the right policy for the 1920s but the wrong policy for the 1930s once Hitler had come to power. During the Weimar Republic, it was possible to negotiate with Germany without the threat of militarisation and war. Appeasement would thus rectify the flaws of the Versailles Treaty by diplomatic means. From 1933, however, with Hitler intent on military aggression, Appeasement by definition would be doomed to failure.Central to British policy at the time was the preservation of peace and the avoidance of war in the long term, irrespective of diplomatic efforts to revise the Versailles Treaty by mutual agreement. After World War I, there was intense debate at the highest levels of British politics, the armed forces and business as to why World War I had been such a disaster, lasting four gruelling years rather than the anticipated four months. The vast loss of life had been accompanied by a loss of wealth. Britain had ended World War I financed by loans from American banks, calling into question the sustainability of the Empire which had been shaken to its foundations.Britain’s status as a great power ‒ epitomised by its navy, the largest and most commanding globally ‒ had been compromised. From the 1920s, therefore, Appeasement was tied to the preservation of the Empire. The Treasury, Britain’s finance ministry, adopted the ‘ten-year rule’ in 1922, confidently reasserted in 1932, that over the next decade, another war would be avoided, preventing the need for a massive increase in spending on rearmament. If Appeasement could guarantee peace in Europe, it would also guarantee the safety, stability and endurance of the British Empire. Appeasement, therefore, was regarded as a win–win policy in the period up to 1933.After Hitler came to power, the British government had to determine whether to continue the policy, modify it or abandon it. These foreign-policy options increasingly divided the Conservative Party, parliament and public opinion as the decade went on. British governments initially maintained the default position of supporting Appeasement after 1933 in the hope that Hitler would accept revision of the Versailles Treaty in return for halting his bellicose threats of military force. In this context, rearmament was downplayed and a flurry of diplomatic initiatives was undertaken to placate Hitler and, to a lesser extent, Mussolini. - eBook - PDF

In Defence of Canada Volume II

Appeasement and Rearmament

- James Eayrs(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- University of Toronto Press(Publisher)

Ill Appeasement A T T H E R H I N E L A N D Her Appeasement now may have the effect of turning her into a bulwark against the on-coming Bolshevism of eastern Europe. The words are those of Jan Christiaan Smuts, in a letter to Lloyd George of 26 March 1919 protesting the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, and urging upon the British the wisdom of applying to Germany the same political magnanimity which they had displayed at Vereeniging seventeen years before. It was an early appearance of the word Appeasement in the vocabulary of politics. Appeasement figured (though without result) in the diplomacy of the peace settlement. It was revised at the time of Locarno and, as Smuts' biographer has noted, from that time onwards was Briand's favourite word, the symbol of a policy towards Germany entirely opposed to that which Poincare had been pursuing. In the Briand-Stresemann era the word, both in its French and English versions, signified reconciliation. Unfortunately, the word can also signify the satisfaction of immoderate appetites. During the 1930's statesmen like Simon and Halifax continued to intend the first meaning while Hitler and Mussolini were intending the second. 1 Only after it became evident that the appetites of the dictators had grown with feeding did appease-ment acquire its present pejorative connotation and become not so much a description as an epithet. The attempt to appease Hitler began in the days following 7 March 1936, when the Nazi leader made good his earlier threat to violate the Locarno agreements if France ratified her pact with the Soviet Union. A scanty detachment of the Wehrmacht was ordered by Hitler into the demilitarized zone of the Rhineland. It was prepared, we know now, to beat a hasty retreat in the event of determined military resistance - eBook - PDF

From Versailles to Pearl Harbor

The Origins of the Second World War in Europe and Asia

- Margaret Lamb, Nicholas Tarling(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Academic(Publisher)

Chapter 6 Appeasement Post-war discussions of international developments in the 1930s were inevit-ably influenced by the knowledge that a major war did break out in Europe in 1939 and in Asia in 1941 and that in the early years of the fighting the Germans and the Japanese won massive military victories. As far as Europe was concerned, it was assumed that Hitler had planned and pre-pared for the war which came. The statesmen of Britain and France who had made concessions to Italy and Germany until the eve of war and allowed them to extend their control over much of continental Europe were roundly condemned. Appeasement, which had been seen as an hon-ourable policy of seeking to reduce strife and achieve a general pacification amongst nations, was now viewed as a weak dishonourable policy of simply giving way to demands. If negotiations had been designed to buy time for the democracies to further their own military preparations, why, it was asked, were they so apparently unprepared for the German onslaught when it came? 1 With the passage of time and with greater historical research, there have been a variety of answers to this question and a reassessment of the policies of all the major powers. The view of Hitler as the master planner was dramatically challenged by A. J. P. Taylor in his Origins of the Second World War , first published in 1961, which claimed that Hitler had had no detailed plan of aggression and had not intended to embark on a major war in 1939. A vigorous debate followed this attack upon the then orthodoxy. 2 The extreme views of seeing Hitler as a master planner or as a supreme opportunist gradually gave way to a more balanced interpretation of his role. It was acknowledged that the precise order of developments which Hitler had outlined in Mein Kampf did not eventuate, but that did not mean that he had deviated from his broad goals of the domination of Europe and the conquest of Lebensraum . - Professor Jeffrey Record(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Lucknow Books(Publisher)

This is not to embrace historical determinism; rather it is simply to argue that the alignment of political, military, and psychological factors in the 1930s were never such as to offer both London and Paris simultaneously a clear appreciation of the nature and scope of the German threat, as well as the opportunity to employ military force confidently and effectively against that threat. In hindsight, it is easy to condemn Appeasement because it led to World War II, but until 1939, the record of Appeasement was one of sparing Europe from war. Chamberlain and Daladier could not know they were making pre-World War II decisions, on the contrary, they were struggling to avoid war. But not at any cost. When in 1939 Hitler violated the Munich Agreement and, in so doing, dispelled any lingering doubts in London and Paris about his real intentions in Europe, Chamberlain and Daladier committed to a policy of war by extending defense guarantees to Poland and other threatened states. WHY DID Appeasement FAIL? Anglo-French Appeasement of Hitler failed for the simple reason that Hitler was unappeasable. He wanted more, much more, than Britain or France could or would give him. Chamberlain sought to propitiate Germany within the framework of Europe’s traditional balance of power system; Hitler sought to overthrow that system. He fooled Chamberlain (and many others in Europe, including conservative German nationalists) into believing that Nazi Germany’s foreign policy ambitions, like those of the Weimar Republic, were limited to rectification of the ‘injustices” of the Versailles Treaty, and until 1939 he was careful to limit Germany’s explicit territorial demands to Germanic Europe, demands he justified in the name of national self-determination. In this regard, British policy toward Germany was consistent from 1919 on: it sought to bring “Germany back into the community of nations. .- eBook - ePub

Politics and Strategy

Partisan Ambition and American Statecraft

- Peter Trubowitz(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

and domestic incentives. What differentiates appeasers (satisficers) from balancers or expansionists are the parameters of choice—the combination of international and domestic incentives that shape strategic choice. As I show in the next chapter, when those incentives change, so too does the type of strategy leaders prefer.1 Indeed, one of the main criticisms of Appeasement is that such concessions only whet the adversary’s appetite for additional concessions. See, for example, Mearsheimer (2001).2 Buckpassing and bandwagoning are other responses that cross-pressured leaders sometimes favor. In the case studies, I explain why Appeasement was preferred to buckpassing and bandwagoning.3 In all three cases, the U.S. faced multiple threats. I focus here on the primary challenger.4 See, for example, Flexner (1974); F. McDonald (1974); Ellis (2004); Harper (2004); and Henriques (2006). Some historians view Washington’s strategy as neutrality rather than Appeasement. However, given the many concessions Washington made to Britain at France’s expense, Appeasement seems more apposite. In any event, the difference is not essential for my argument. Appeasement and neutrality are both inexpensive status quo strategies that cross-pressured leaders may turn to when they have little geopolitical slack, and military expansion does not pay domestically.5 On the general history of the Jay Treaty, see Bemis (1962) and Coombs (1970).6 To many Americans, this was but the latest in a series of high-handed British economic policies since the 1783 Treaty of Paris that had given America its independence. London continued to occupy many frontier posts in U.S. territory in violation of the terms of the 1783 treaty. The British army used those posts to funnel arms from Canada to Indian tribes to slow the advance of American settlers and protect British fur-trading interests in the region.7 - eBook - ePub

The Use and Abuse of Memory

Interpreting World War II in Contemporary European Politics

- Christian Karner(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

In his speech delivered on 17 March 2003, ostensibly directed toward giving Saddam Hussein forty-eight hours to leave Iraq and avoid war, US President George W. Bush (2003) referred to the continuation of inspections without full compliance as “a policy of Appeasement.” Of course, his was certainly not his first allusion to the context of WWII. In his address to the United Nations General Assembly earlier on in the process, Bush (2002) had challenged the UN to ensure that it did not suffer the same fate as its predecessor, the League of Nations, by failing to act with conviction in relation to Iraq’s violation of UN Resolutions.A prime example of this process of accusation in the UK parliament, invoking various aspects of the context of WWII, and the 1930s before it, comes from Julian Lewis (Conservative), as follows:Plenty of people argued that it was wrong to take action against the Nazis, until it became so late that the action that had to be taken proved much more costly than that which could have been taken earlier. Had such action been taken earlier, it would have been denounced as unwarranted and pre-emptive.[. . .] Those who said, in advance of the action that was eventually taken against the Hitlerite regime, that no action was justified get a bad press, because they are now regarded as having no reasonable arguments. Let me assure you, Mr. Deputy Speaker, that if we could revisit the debates that took place in this House in the 1930s, we would hear arguments for Appeasement just as sophisticated as those put forward today. Those arguments were wrong then, and they are wrong now. It will be a grave mistake if people think that the cause of peace is served by always avoiding conflict. Sometimes the only way to bring peace is to face up to the need for conflict, and this is one of those occasions. (Hansard 2003a: 333) - eBook - PDF

Nothing Less than Victory

Decisive Wars and the Lessons of History

- John David Lewis(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

The Appeasement that Hitler leveraged so master-fully was an application of this method. British policymakers were concerned with an increasingly vulnera-ble global empire, within which European squabbles could look much less threatening than a crisis in Asia or India. Britain’s trade and for-eign investments had fallen drastically since World War I and during the 1920s. Britain was saddled with foreign colonies taken from Ger-many—a financial drain that could not be defended militarily. Britain had to choose its battles carefully; it was unable to project power across its empire and was economically unprepared for another long war. Further, many British did not see Germany as the major threat to their empire; Russia and Japan were arguably more worrisome. It was important, many thought, to avoid entanglements in European defen-sive pacts—a Britain so occupied could lead the Japanese to take ad- “THE BALM FOR A GUILTY CONSCIENCE” 201 vantage of British weakness in the Pacific, which could cause violence in the Middle East. One way to lower tensions and avoid trouble, many people believed, was to pressure France to make concessions to Germany. The Ruhr River crisis in January of 1923 is again a case in point. The occupation might not have been necessary had the British and Americans supported French and Belgian demands that Germany comply with the treaty. But Britain abstained from the vote to declare Germany in default because, in the analysis of Sally Marks, to admit that Germany was in violation of the treaty would have required the British and Americans to do something, and they did not want to act. 41 French occupation took the blame for the German economic distress, and international pressure rose to reverse the injustice. Brit-ain tried to walk a middle path. To support France against Germany would sanction an outrage that could lead to no good result, but to repudiate payments outright was politically impossible. - eBook - ePub

When Things Go Wrong

Foreign Policy Decision Making under Adverse Feedback

- Charles F. Hermann(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Diplomacy of Illusion. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. Mommsen, Wolfgang and Lothar Kettenaker, eds. 1983. The Fascist Challenge and the Policy of Appeasement. London: George Allen & Unwin.Newman, William J. 1968. The Balance of Power in the Interwar Years. New York: Random House.Nye, Joseph. 1987. “Nuclear Learning and U.S. Security Regimes.” International Organization 41(3): 371–402.Parker, Robert Alexander Clarke. 1993. Chamberlain and Appeasement. London: The Macmillan Press, Ltd.Parliamentary Debates 1937–1943. House of Commons Official Reports. London: H.M.S.O. Post, Gaines. 1992. Dilemmas of Appeasement. Ithaca, NY: Cornell.Robbins, Keith. 1997. Appeasement, 2nd edn. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.Rock, Stephen R. 2000. Appeasement in International Politics. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.Rock, William R. 1977. British Appeasement in the 1930s. New York: W.W. Norton. Rokeach, Milton. 1960. The Open and Closed Mind. New York: Basic Books.Rokeach, Milton. 1968. Beliefs, Attitudes, and Values. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Schafer, Mark and Stephen G. Walker. 2006a. Beliefs and Leadership in World Politics. New York: Palgrave-Macmillan.Schafer, Mark and Stephen G. Walker. 2006b. “Democratic Leaders and the Democratic Peace: The Operational Codes of Tony Blair and Bill Clinton.” International Studies Quarterly 50(3): 561–584.Schweller, Randall. 1998. Deadly Imbalances. New York: Columbia University Press.Schweller, Randall. 2001. “The Twenty Years’ Crisis: Why a Concert Didn’t Arise.” In Bridges and Boundaries: Historians, Political Scientists, and the Study of International Relations, ed. Colin Elman and Miriam Elman. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 181–212.Taylor, Alan John Percivale. 1961. The Origins of the Second World War. New York: Athenaeum.Tetlock, Philip. 1991. “In Search of an Elusive Concept.” In Learning in U.S. and Soviet Foreign Policy, ed. George Breslauer and Philip Tetlock. Boulder: Westview Press, 20–61.Tetlock, Philip. 1998. “Social Psychology and World Politics.” In Handbook of Social Psychology - eBook - PDF

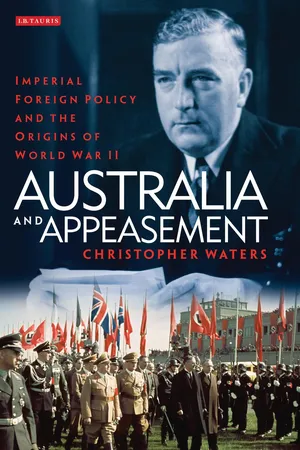

Australia and Appeasement

Imperial Foreign Policy and the Origins of World War II

- Christopher Waters(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- I.B. Tauris(Publisher)

1 THE ORIGINS OF THE IMPERIAL Appeasement POLICY Adolf Hitler secured power in Germany on 30 January 1933. For the first weeks of government the Nazis relied on a coalition of parties to maintain power, but Hitler soon moved ruthlessly to consolidate his position. A new political force emerged onto the European stage and threatened the status quo that had been established by the vic-tors at the end of the First World War. For the Australians who thought deeply about foreign affairs Nazi Germany posed serious questions about the peace of Europe and the security of the British Empire. The youthful Federal Attorney-General, Robert Menzies, on his first trip to the United Kingdom and Europe in 1935, defined the major question faced by policy-makers throughout this terrible decade: and in the last resort the prospects of peace during the next ten years depend to an amazing extent upon whether Hitler is a real German patriot, who seeks only to restore the self-respect of his country, or a mad swashbuckler, who is consciously pre-paring for war, in order to revive a state of military glory. 1 Was Hitler’s foreign policy limited to the removal of the restrictions on German sovereignty and revision of the territorial adjustments 6 Australia and Appeasement that had been imposed through the Treaty of Versailles? Or did he have a grander plan for German domination of Europe, and perhaps the rest of the world, based in Nazi racial ideology as laid out in his tract Mein Kampf ? What should be done about Hitler and Nazi Ger-many, Mussolini and fascist Italy, and a militarised and expansionist Japan? Should peace be secured by making concessions or by devel-oping an alliance of great powers directed at containing the dictator states? These were the difficult questions the Australian governments of the 1930s had to answer. - eBook - ePub

- Gordon Martel(Author)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

To do so is difficult not merely because British attitudes and actions were, in Taylor’s book, integrated into the overall story of why the Second World War occurred but because our own judgments of how well-founded, say, were Whitehall’s worries about the size of the Luftwaffe will be affected by new researches on German aerial rearmament. Similarly, our assessments of British policy towards Poland, Russia and the USA in the 1930s can be placed in a different light by newly released archival materials from those countries, as well as from France, Japan and other actors. Above all, the issue of how well, or how poorly, the British understood Hitler’s real intentions can be fully analyzed only by reference to scholarship on German policy, which is outside the bounds of this particular essay. 4 Students wishing to comprehend British Appeasement will always need to understand other, non-British, perspectives as well. The enormous literature on “the meaning of Appeasement” 5 can be dealt with briefly here, since its significance for our purposes lies chiefly in the way Taylor’s revisionist work challenged a well-established orthodoxy. Although Appeasement originally was a positive concept – as in the “appeasing” of one’s appetite – the failure of Neville Chamberlain’s policies turned it into a pejorative term by 1939, a tendency which grew ever stronger as the costs of the war mounted and the full horrors of Nazi policy were gradually revealed. Since Hitler was by then regarded as the Devil incarnate, it followed that Chamberlain and Daladier’s diplomacy in the late 1930s had been hopelessly misconceived and morally wrong. 6 Instead of standing up to the führer’s manic ambitions, they had weakly appeased them. Taylor’s revisionism assaulted this orthodoxy on both the intellectual and the moral front. In his view, the restoration of Germany as a leading power, if not the leading power, in Europe was natural and inevitable

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.