History

Art Deco Architecture

Art Deco architecture emerged in the 1920s and 1930s, characterized by its sleek, geometric forms, bold colors, and decorative motifs. It often features symmetrical designs, stepped forms, and intricate detailing. Art Deco buildings can be found in major cities around the world and are known for their modern, glamorous, and luxurious aesthetic.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Art Deco Architecture"

- eBook - ePub

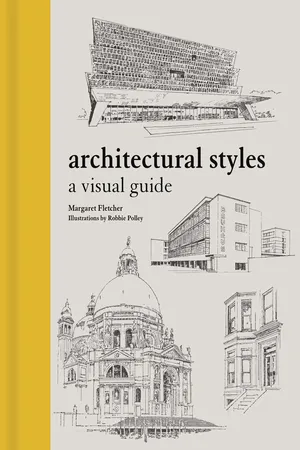

Architectural Styles

A Visual Guide

- Margaret Fletcher, Robbie Polley(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

4

MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY

ART DECO

TWENTIETH CENTURY

The Art Deco style is synonymous with luxury, yet is accessible to all, encompassing all arts, architecture, design, visual arts, as well as everyday objects. The name Art Deco is derived from the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts held in Paris in 1925—the Arts Décoratifs. Intended to re-establish Paris as the center of design, the exhibition brought together modern ideas on design, while referencing scale, proportion, and symmetry from Classical Greek and Roman examples. The style was heavily influenced by geometric references of Cubism, as well as a nod toward Eastern cultures such as Japan, China, Persia, and India.Art Deco key features:- geometric patterns

- rectilinear lines

- curved building forms

- glamour and luxury

- reinterpretation of Classical elements

- low relief sculptural ornamentation

- detailed craftsmanship

Odeon Cinema, Kingstanding, England, 1935–36, Harry Weedon and Cecil Clavering, architects.As the first cinema in the Odeon chain for Oscar Deutsch, this brick Art Deco theater set the standard for others in the chain. With a large curved front and vertical billboard, it is a quintessential representation of Art Deco architectural drama.Marlin Hotel, Miami, Florida, US, 1939, L. Murray Dixon, architect.As one of Miami’s first boutique hotels, this South Beach landmark is three stories tall, with a prominent ornamental vertical thrust over the entrance, and curved glass and sun shields wrapping around each side of the building.Mutual Building, Cape Town, South Africa, 1936–39, Louw & Louw Architects, architects.These sculptures, located above one of the entrances, are carved in granite and represent the nine ethnic groups of Africa. The building, built in reinforced concrete and clad in granite, forms a ziggurat structure with vertical angled or triangled windows extending up and down the height of the building. - eBook - ePub

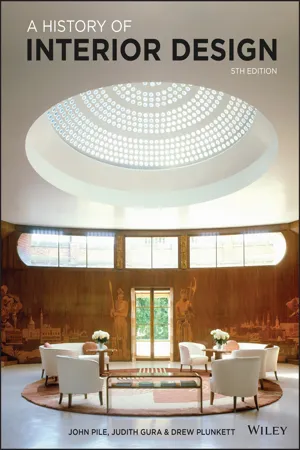

- John Pile, Judith Gura, Drew Plunkett(Authors)

- 2024(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN Art DecoThe luxurious decorative work exhibited at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts of 1925 in Paris was described as Style Moderne (Modern Style). Designers whose work would be classified as Moderne, worked without any sense of obligation to traduce tradition but they understood the time they lived in and designed as they felt appropriate for it—there were few references to the past. American art historian Jeanne Willette said that the arrival of Style Moderne represented the point at which signifiers of modernity became fashionable, when objects in the style made either by hand or machine from natural or artificial materials were prized as symbols of modernity. Modernists liked to insist that their work was driven by philosophy and not style, which was, they implied, ephemeral and superficial. Le Corbusier, and his followers used “art déco” (decorated art) as a, perhaps playfully derogatory, description of any modern work that seemed concerned with fashion or traditional aesthetics.In the 1960s, when modernist architecture was at its least popular, Style Moderne found its name and its admirers. What began as a term of abuse was legitimized in 1968 when the British historian Bevis Hillier used “Art Deco”—ironically—as the title of his book on the period and the style. Art Deco then became the retrospectively acceptable label for a distinct and democratic style, which was considered less pure because it was less austere. Historians, critics, and academics are generally uncomfortable with what may seem frivolous and practitioners of Art Deco issued no manifestoes to suggest serious intent—it was a laissez-faire strand of design. Its practitioners broadly shared a visual language but did not demand creative conformity. They admired the machine-made but did not prioritize function or technology. It was less doctrinaire and its output too diverse to be easily classifiable, too uncontentious—and charming—to draw polemical attention to itself but it was undoubtedly modern. It did not recycle past aesthetics but it understood that reductive hardline modernism would thwart the potential of interiors. - eBook - ePub

- John Pile, Judith Gura, Drew Pile, Drew Plunkett(Authors)

- 2024(Publication Date)

- Laurence King Publishing(Publisher)

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

Art Deco

18.1 Rolf Engströmer, entrance hall, Eltham Palace, London, 1934.The circular entrance hall to the new part of the house—added to the rebuilt sixteenth-century shell of Eltham Palace—with its marquetry wall decoration and circular glazed dome.The luxurious decorative work exhibited at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts of 1925 in Paris was described as Style Moderne (Modern Style). Designers whose work would be classified as Moderne, worked without any sense of obligation to traduce tradition but they understood the time they lived in and designed as they felt appropriate for it—there were few references to the past. American art historian Jeanne Willette said that the arrival of Style Moderne represented the point at which signifiers of modernity became fashionable, when objects in the style made either by hand or machine from natural or artificial materials were prized as symbols of modernity. Modernists liked to insist that their work was driven by philosophy and not style, which was, they implied, ephemeral and superficial. Le Corbusier, and his followers used “art déco” (decorated art) as a, perhaps playfully derogatory, description of any modern work that seemed concerned with fashion or traditional aesthetics.In the 1960s, when modernist architecture was at its least popular, Style Moderne found its name and its admirers. What began as a term of abuse was legitimized in 1968 when the British historian Bevis Hillier used “Art Deco”—ironically—as the title of his book on the period and the style. Art Deco then became the retrospectively acceptable label for a distinct and democratic style, which was considered less pure because it was less austere. Historians, critics, and academics are generally uncomfortable with what may seem frivolous and practitioners of Art Deco issued no manifestoes to suggest serious intent—it was a laissez-faire strand of design. Its practitioners broadly shared a visual language but did not demand creative conformity. They admired the machine-made but did not prioritize function or technology. It was less doctrinaire and its output too diverse to be easily classifiable, too uncontentious—and charming—to draw polemical attention to itself but it was undoubtedly modern. It did not recycle past aesthetics but it understood that reductive hardline modernism would thwart the potential of interiors. - eBook - ePub

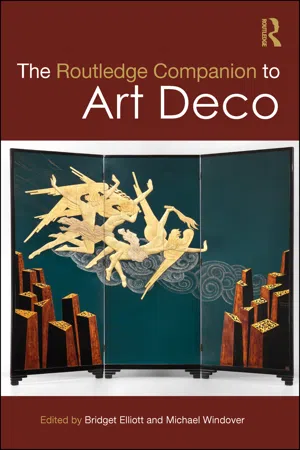

- Bridget Elliott, Michael Windover, Bridget Elliott, Michael Windover(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

In the hothouse atmosphere of the economic boom, speculative buildings proliferated, and with them an overwhelming interest in the decorative modernism of Art Deco. In buildings of this kind—predominantly apartment and office blocks—the expression of modernity was still essentially within a classical understanding of symmetrical planning behind a symmetrical façade. The enrichment on the façade, however, began to explore an expanded range of decorative motifs, including abstract, geometric forms as well as stylized plant and animal motifs. Sometimes, these were related iconographically to the building’s function, sometimes not. Elsewhere, as I discuss in the final section of this chapter, they would be implicitly conflated with specific constructs of national identity. But what they had in a common was a commitment to, and celebration of, notions of modernity, progress, and urban self-consciousness. Figure 13.3 Art Deco buildings in Springs, c. 1934. Photo: Federico Freschi © 2016. Interesting in this regard is the decorative program of Dunvegan Chambers (designed by Cook and Cowen in 1934), a ten-story office block in Johannesburg (Figure 13.4). Designed for dentists and other professional tenants, the building is situated on a corner site in the (then) central business district. The tower block has projecting bays rising to eighth-floor level on both street frontages and is characterized by two interesting elements: first, it has two vertical fins arising from the mullions of the bays on the street frontages, which are detached at the upper floor levels, and crested over the top of the building. This, along with the setback effect above the bays, creates a sweeping impression of height, reinforced by the Art Deco-style parapet at the end of the vertical members on the roofline. The streamlined fins, as Chipkin (1993, 110) suggests, “carry the emotional charge of cult objects of the 1930s,” namely streamlined racing cars, aircraft, and steam engines - eBook - ePub

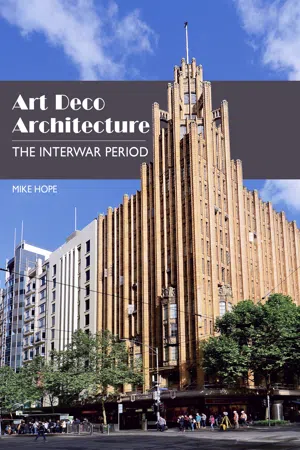

Art Deco Architecture

The Interwar Period

- Mike Hope(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Crowood(Publisher)

Chapter 5 ART DECO AROUND THE WORLDCassiano Branco and Carlo Florencio Dias, The Eden Theatre, Praça dos Restauradores, Lisbon, Portugal. 1931. Detail of central relief carving on front facade.T his chapter celebrates examples of Art Deco Architecture from some unexpected places, often with a regional twist, looking beyond the more famous and oft-cited examples such as Napier in New Zealand and Havana in Cuba, to view buildings in such diverse locations as Durban, Mumbai, Sydney, the Philippines and Indonesia. From South and Central America, other less well known but nevertheless stunning examples will be discussed and shown, from Buenos Aires and Mexico City. Through the use of specific case studies the opportunity will be taken to introduce a new set of buildings and architects.The world in the 1920s and 1930s was still very much one of large colonial empires. The British, French, Belgian, Portuguese, Netherlands and Italian empires had very much benefited from the dismemberment of the German empire after the Treaty of Versailles. As a result many of the latest architectural trends naturally flowed around these empires. Likewise, the influence of not only those countries’ film industries, but above all Hollywood helped to spread the seeds of Art Deco architectural style around the world. Indeed America continued to be seen not only as the destination for immigrants from all over the world, but as having a new-found status and culture, which would signal the start of its rise to world pre-eminence both politically and culturally.EuropeOutside of France and Britain, the rest of Europe would follow a similar pattern in embracing the various elements of Art Deco architectural styles to a lesser or greater degree. Architecturally speaking, those countries with totalitarian regimes would not tend to erect many buildings in what can be termed Art Deco. Instead such countries as the Soviet Union, Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy would create their own brands of monumental architecture that drew heavily, although not entirely, on the Stripped Neo-Classicism, which by the end of the 1930s was apparent in virtually all countries. As a result I have chosen to represent the Netherlands comprehensively with further examples from Ireland, Spain and Portugal. - eBook - PDF

American Pop

Popular Culture Decade by Decade [4 volumes]

- Bob Batchelor(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

This style of residential architecture gained popularity after the 1915–1916 Panama-California Exposition held in San Diego. This style reached its zenith in the 1920s and early 1930s but fell rapidly out of favor during the 1940s. “Own Your Own Home.” This ad from Sears Roebuck and Co. promotes their home building plans. Architecture Architecture of the 1920s | 261 INTERIOR DESIGN Middle-class Americans during the 1920s consciously decorated their homes and offices to reflect their personal style and taste. While Art Deco and the International Style exerted consid- erable influence on those individuals most at- tuned to architectural and stylistic trends, most Americans favored more traditional design styles. General advice about interior decorating was easy to find. House Beautiful, Arts & Decoration, Fruit, Garden and Home (founded in 1922 and renamed Better Homes & Gardens in 1924), and other na- tional magazines offered suggestions about how to arrange furniture, acquire antiques (or repro- ductions), and generally make one’s home more attractive. Even fashion magazines such as Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar published occasional articles about interior design. Eager to capitalize on the newfound interest in home decorating, publishers released dozens of interior design guidebooks, including Ethel Davis Seal’s famous Furnishing the Little House (1924). Wealthy and fashionable homeowners often hired professional designers to provide them with interior decors that were elegant, tasteful, and harmonious. Although few people completely furnished their homes with Art Deco objects, this style did creep into the living rooms, bedrooms, and kitch- ens of millions of ordinary Americans. Oriental- looking lacquered screens, stylized ceramic statues, geometrically patterned floor coverings, inlaid dressing tables, and goods constructed of man-made materials such as plastics, glass, and chrome all represented the new Art Deco look. - eBook - ePub

Culture, Class, and Critical Theory

Between Bourdieu and the Frankfurt School

- David Gartman(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

By the 1920s this peripheral architecture began to infiltrate the centers of many American cities through migrating places of mass entertainment. Corporate office buildings also began to adopt aspects of this style, for in this age of advertising, companies realized that they too needed to project an enticing image to the consuming masses. Thus, architects commissioned to design buildings for producers of mass consumer goods were, like the artists and designers directly employed by them, also exposed to the demands of the mass market.The architectural style that rose to dominance in this age of mass consumption was known variously as moderne, modernisitic, or Art Deco. Its underlying objective, determined by the imperatives of the mass market, was to create an aesthetic unity that obscured the fragments of production. In urban skyscrapers the visibility of standardized, mass-produced floors was an unwelcome reminder of the rationalized production process, so architects designed building exteriors in a unifying and decorative aesthetic that obscured these fragmented parts (Koolhaas 1994: 100–4). For example, Ralph Walker's pioneering design for the Barclay-Vesey building of 1926 disguised the separate floors with a series of continuous piers, separated by recessed spandrels, which ran up the entire height of the building. Then he added simplified Gothic decoration on the exterior, along with naturalistic Art Noveau embellishments on the interior, to relieve the rectilinearity. Lewis Mumford wrote that this “decoration is an audacious compensation for the rigor and mechanical fidelity of the rest of the building: like jazz, it interrupts and relieves the tedium of too strenuous mechanical activity” (quoted in Tafuri 1990: 183). Another skyscraper-cum-advertisement, the Chrysler building, sported an elaborately ornamental, six-story, stainlesssteel spire whose arches were reminiscent of car radiators, in order to catch consumers' attention and advertise the corporation's products (Wilson et al. 1986: 150–65). - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- The English Press(Publisher)

Pablo Picasso experimented with classicizing motifs in the years immediately following World War I, and the Art Deco style that ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ peaked in the 1925 Paris Exposition des Arts Décoratifs often drew on neoclassical motifs without expressing them overtly: severe, blocky commodes by E. J. Ruhlmann or Sue et Mare; crisp, extremely low-relief friezes of damsels and gazelles in every medium; fashionable dresses that were draped or cut on the bias to recreate Grecian lines; the art dance of Isadora Duncan; the Streamline Moderne styling of US post offices and county court buildings built as late as 1950; and the Roosevelt dime. Neoclassicism Part II: Between the Wars There was an entire 20th century movement in the Arts which was also called Neo-classicism. It encompassed at least music, philosophy, and literature. It was between the end of World War I and the end of World War II. This literary neo-classical movement rejected the extreme romanticism of (for example) dada, in favour of restraint, religion (specifically Christianity) and a reactionary political program. Although the foundations for this movement in English literature were laid by T. E. Hulme, the most famous neoclassicists were T. S. Eliot and Wyndham Lewis. In Russia, the movement crystallized as early as 1910 under the name of Acmeism, with Anna Akhmatova and Osip Mandelshtam as the leading representatives. Neoclassicism in Russia and the Soviet Union Ostankino Palace, designed by Francesco Camporesi and completed in 1798, in Moscow, Russia In 1905–1914 Russian architecture passed through a brief but influential period of neoclassical revival; the trend began with recreation of Empire style of alexandrine period and quickly expanded into a variety of neo-Renaissance, palladian and modernized, yet recognizably classical schools. They were led by architects born in 1870s, who reached creative peak before World War I like Ivan Fomin, Vladimir - eBook - ePub

American Architecture

A History

- Leland M. Roth, Amanda C. Roth Clark(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

This was a pragmatic and utilitarian American Modernism rather than one advancing a polemical position. Smooth white plastered walls, horizontal ribbon windows, chrome and stainless steel, and dramatic colors might be employed (paralleling work of Bauhaus-trained designers in Germany), but façades and plans were often symmetrical, a feature assiduously avoided by Bauhaus designers. Residential examples ranged from the boldly rounded Earl Butler house by architects Kraetsch & Kraetsch in Des Moines, Iowa, 1935–1937, to the refined and minimal elegance of the William Lescaze townhouse, New York City, 1934, and the Richard H. Mandel house in Mt. Kisco, New York, 1935, by Edward Durell Stone with Donald Deskey. 25 Public buildings of all sorts were also done in both Art Deco and Moderne styles. One of the most visually striking of the Moderne public buildings is the Cincinnati Union Terminal, 1933, designed by Fellheimer & Wagner, recently remodeled for commercial use [ 8.37 ]. In Miami Beach, on the Atlantic shore east of the city of Miami, Streamline Moderne and Art Deco forms shaped an entire district of small tourist hotels and small apartment blocks built up between 1926 and 1940. The district abounds in examples, standing side by side, replete with elongated vertical masts or extended horizontal window bands, corner windows or rounded corners, smooth white walls set off with mustard yellow, flamingo pink, aqua blue, or lime green, and featuring panels of flattened foliate and geometric designs. The group of small hotels beside the Colony Hotel, 1935, by Henry Hohauser, is emblematic of Miami Beach Art Deco [ 8.38 ]. 8.37. Fellheimer & Wagner, Cincinnati Union Terminal, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1933. Using sweeping concentric circles in the elevation, the architects adapted the strong geometric character of the Moderne style to a large public building - Craig Cravens(Author)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

New build- ing materials, especially reinforced concrete, enabled a more open layout without the necessity of supporting structures such as pillars. Functionalism is considered one of the finest trends in Czech architecture and was used on large administrative buildings and some private dwellings. The third archi- tectural movement of the first decades of the twentieth century is Cubism, an exclusively Czech trend theorized and practiced by a small group of artists who sought to turn it into a national Czechoslovak style. Even though some buildings were constructed in this manner, it never achieved mass popular- ity. Socialist Realism arrived from the Soviet Union in the 1950s, but only two hotels—the International and the Jalta—were constructed in this style. Most building efforts in the 1950s and 1960s were concentrated on creating mass housing developments of monotonous, prefab buildings referred to as paneláks. ARCHITECTURE 173 Art Nouveau In its early years, Art Nouveau represented a reaction against the contem- porary preference for emphasizing historical forms. Columns and pilasters gradually disappeared, giving way to new “naturalistic” motifs, such as veg- etable and fruit ornamentation. Architects also employed intricate patterns emphasizing geometry. Curved roofs began to top buildings, and natural stone and colored glass were used abundantly. Art Nouveau architects tried to bridge the crafts and the arts; they saw the building as an artistic totality and concentrated their attention on the smallest architectural details, such as grille work and door handles. At the same time they would make visible some of the most fundamental structural features of the building. The Art Nouveau artist sought to strike a balance between man and nature using artistic symbols to add a spiritual dimension to personal experience.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.