History

Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme was a major offensive of World War I, fought between July and November 1916. It was a joint British and French operation against the German army, and it resulted in heavy casualties on both sides. The battle is remembered for the significant loss of life and the limited territorial gains made by the Allies.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Battle of the Somme"

- No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- College Publishing House(Publisher)

The Battle of the Somme was one of the largest battles of the First World War: by the time fighting had petered out in late autumn 1916 more than 1.5 million casualties had been suffered by the forces involved, making it one of the bloodiest military operations ever recorded. The plan for the Somme offensive evolved out of Allied strategic discussions at Chantilly, Oise in December 1915. Chaired by General Joseph Joffre, the commander-in-chief of the French Army, Allied representatives agreed on a concerted offensive against the Central Powers in 1916 by the French, British, Italian and Russian armies. The Somme offensive was to be the Anglo-French contribution to this general offensive, and was intended to create a rupture in the German line which could then be exploited with a decisive blow. With the German attack on Verdun on the River Meuse in February 1916, the Allies were forced to adapt their plans. The British Army took the lead on the Somme, though the French contribution remained significant. The opening day of the battle on 1 July 1916 saw the British Army suffer the worst one-day combat losses in its history, with nearly 60,000 casualties. Because of the composition of the British Army, at this point a volunteer force with many battalions ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ comprising men from specific local areas, these losses had a profound social impact and have given the battle a lasting cultural legacy in Britain. The casualties also had a tremendous social impact on the Dominion of Newfoundland, as a large percentage of the Newfoundland men that had volunteered to serve were lost that first day. The battle is also remembered for the first use of the tank. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- University Publications(Publisher)

The Battle of the Somme was one of the largest battles of the First World War: by the time fighting had petered out in late autumn 1916 more than 1.5 million casualties had been suffered by the forces involved, making it one of the bloodiest military operations ever recorded. The plan for the Somme offensive evolved out of Allied strategic discussions at Chantilly, Oise in December 1915. Chaired by General Joseph Joffre, the commander-in-chief of the French Army, Allied representatives agreed on a concerted offensive against the Central Powers in 1916 by the French, British, Italian and Russian armies. The Somme offensive was to be the Anglo-French contribution to this general offensive, and was intended to create a rupture in the German line which could then be exploited with a decisive blow. With the German attack on Verdun on the River Meuse in February 1916, the Allies were forced to adapt their plans. The British Army took the lead on the Somme, though the French contribution remained significant. The opening day of the battle on 1 July 1916 saw the British Army suffer the worst one -day combat losses in its history, with nearly 60,000 casualties. Because of the ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ composition of the British Army, at this point a volunteer force with many battalions comprising men from specific local areas, these losses had a profound social impact and have given the battle a lasting cultural legacy in Britain. The casualties also had a tremendous social impact on the Dominion of Newfoundland, as a large percentage of the Newfoundland men that had volunteered to serve were lost that first day. The battle is also remembered for the first use of the tank. - Glyn Stone, Thomas G. Otte(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

THE ANGLO–FRENCH VICTORY ON THE SOMME William PhilpottThe 1916 Somme offensive, 141 days of hard attritional slogging over the slopes of an insignificant range of small hills in Picardy, is generally judged to epitomise the “futility and slaughter” which is shorthand for military operations on the western front in the First World War. The casualties speak for themselves: approximately 420,000 British and 205,000 French, and at least 400,000, arguably as many as 680,000 German, depending on accounting system.1 Why were over 1 million men killed or wounded in a small area of ground of no strategic significance?2 There was little to show for this blood-letting materially, and its impact on morale and fighting capacity, although hotly debated subsequently,3 was unquantifiable. Ergo, being such an unprecedented happening, the Somme has lost its context, ceasing to be an episode—the central episode—in the longer military continuum of the First World War in which allied French and British armies took on and defeated their German opponent in a lengthy war of attrition. It has become an event apart, and is so much studied and argued over that arguably today the Somme has become as much a cultural phenomenon as a military action. However, placing the battle in its proper place in the wartime continuum helps in an understanding of its true nature and impact, shorn of it subsequent notoriety and iconography.The allied commanders and armies judged at the time that they had won a victory—it was their enemies after all who subsequently pulled back their line to new defensive positions and began putting out peace feelers—albeit a hard-won and indecisive one. It would take two further years of fighting before their military superiority was conclusively demonstrated. Nevertheless, it is appropriate to consider why they reached this judgement, and how this battle fitted into their broader strategy.- eBook - ePub

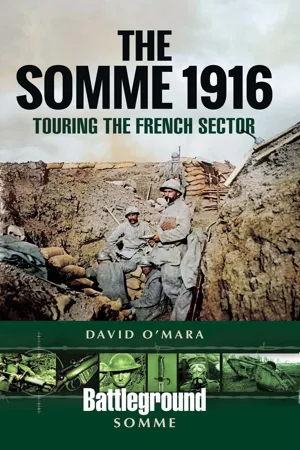

The Somme 1916

Touring the French Sector

- David O'Mara(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Pen & Sword Military(Publisher)

Chapter Three

The Battle of the Somme 1916

Background to the Offensive

Originally conceived as part of a war-winning simultaneous strike on three fronts by all Allied nations, initial planning for what was to eventually become the Battle of the Somme began soon after the Italian declaration of war and as early as June 1915, when it was proposed by the French Commander-in-Chief, général Joseph Joffre, that the Allies (France, Russia, Great Britain, Serbia, Belgium and Italy) should begin to operate more co-operatively with each other and co-ordinate their plans accordingly. This proposal was taken up on 7 July 1915 when the first Inter-Allied Military Conference at Chantilly, Oise (the location of Joffre’s Grand Quartier Général ) was held. Though no specific actions were decided upon at this conference, it was agreed that concentrated, co-operative actions would be the most successful way forward and the foundations were laid for a second, more proactive, conference to be held later that year.Following on from a meeting in Paris between the British Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, and his French counterpart, Aristide Briand, on 17 November 1915, an agreement was made and adopted to form a permanent committee co-ordinating action between the two nations. A further Anglo-French meeting was held in Calais on 4 December 1915, presided over by Lord Kitchener, with the French delegation represented by Briand. Two days later, a second Chantilly Conference was held in which the Allied strategy for 1916 was to be decided. Here it was agreed that offensives by the Allied armies on the War Fronts should be delivered simultaneously or, at least, close enough in time to each other (within a month) so that the enemy would be prevented from being able to transport reinforcements from one front to another. These offensives were planned to commence as soon as was possible, with local, limited attacks taking place in between to further incapacitate and occupy the enemy forces. - eBook - ePub

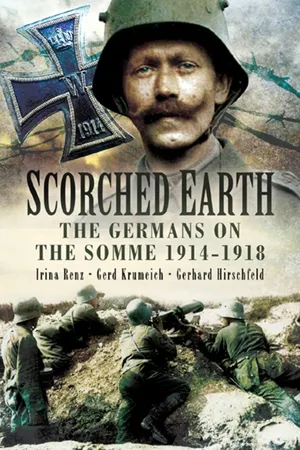

Scorched Earth

The Germans on the Somme, 1914–18

- Gerhard Hirschfeld, Gerd Krumeich, Irina Renz(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Pen & Sword Military(Publisher)

In mid-November 1916, after a temporary improvement in the weather, the last major attack by the British 5th Army (until 1 November the Reserve Army) under General Gough along the Ancre river was considered a disappointment, despite the capture by 51st Scottish Highland Division of Beaumont-Hamel which had been so hard-fought previously on 1 July. The French, who in September had reached Bouchavesnes north of Péronne with heavy losses – their farthest penetration eastwards of the German line, were little able to consolidate their territorial gains in this locality, and made no breakthrough.The towns of Bapaume and Péronne, the hard-fought objectives of the French and British attacks, remained securely in German hands. The Battle of the Somme ‘slowly burned out’, as a popular German military chronicler described it.14 Neither side achieved any noteworthy success: new military technology was tried out by both sides, new operational strategies and tactics were developed or rejected. Both sides claimed to emerge from the battle the victor – the price which they paid to do so was fearsome.The Balance Sheet

The 1916 Battle of the Somme was far and away the bloodiest battle of the Great War. Between 24 June (commencement of the artillery bombardment) and 25 November (provisional end to the fighting), the British lost a total of 419,654 men dead, wounded, prisoner or missing, the French 204,353 and the Germans about 465,000.15 Thus the Allies’ losses were substantially higher than those of the German defenders. The British losses exceeded the worst estimates of their military leaders. The Somme destroyed, in the long term, the fighting ability of twenty-five British divisions;16 put another way, every second British soldier who fought on the Somme was either so seriously wounded as to be unfit for future military service or failed to return at all.For the Germans, the Battle of the Somme represented an enormous ‘bloodletting’ from which the Western Army, already weakened in the offensive before Verdun, would not recover. The Reich archive military historians summarized the Somme losses later: ‘The existing old nucleus of German infantry trained in peacetime bled to death on this battlefield.’17 To replace these experienced soldiers, amongst whom were numerous senior NCOs, there now arrived fresh and often inadequately trained recruits, whose chances of survival were accordingly that much slimmer. Responsibility for the extremely high losses lay not least with the German High Command, which at the beginning of the Battle of the Somme had insisted that the forward trenches be held at all costs. The German front line, as a rule heavily manned, could only be vacated voluntarily with the express authority of High Command.18 - eBook - ePub

The Church Lads' Brigade in the Great War

The 16th (Service) Battalion The King's Royal Rifle Corps. The Long, Long Trail

- Jean Morris(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Pen & Sword Military(Publisher)

Chapter Six1916: The Battle of the Somme On 27 January 1916, conscription into the armed forces of Great Britain was made compulsory. For almost the next three years, dozens of battles were fought simultaneously. Hundreds of paths were crossed by thousands of allied troops attempting to destroy their enemy.Before action By all the glories of the day And the cool evening’s benison, By that last sunset touch that lay Upon the hills where day was done, By beauty lavishly outpoured And blessings carelessly received, By all the days that I have lived Make me a soldier, Lord. By all of man’s hopes and fears, And all the wonders poets sing, The laughter of unclouded years, And every sad and lovely thing; By the romantic ages stored With high endeavour that was his, By all his mad catastrophes Make me a man, O Lord. I, that on my familiar hill Saw with uncomprehending eyes A hundred of Thy sunsets spill Their fresh and sanguine sacrifice, Ere the sun swings his noonday sword Must say goodbye to all of this; By all delights that I shall miss, Help me to die, O Lord. W.N. Hodgson (1893–1916).Serving with the 9th Battalion The Devonshire Regiment, Lieutenant Hodgson was preparing for the Battle of the Somme. The scheduled date for the start of the battle was originally to be in August 1916, but had been brought forward to 29 June. Owing to bad weather during the week leading up to the battle, the date of the attack, now planned for 11:00 hours on 28 June, was moved once again to the morning of 1 July 1916. It is believed that Noel Hodgson wrote the poem on 29 June 1916. - eBook - ePub

From the Somme to Victory

The British Army's Experience on the Western Front 1916–1918

- Peter Simkins(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Praetorian Press(Publisher)

Chapter TwoThe Lessons and Legacy of the Somme: Changing Historical Perspectives

E ver since the mid-to-late 1920s, the conduct of the 1916 Somme campaign by the BEF under Sir Douglas Haig has generally received a bad press. On 1 July each year, on the anniversary of the start of the battle, the Somme offensive is presented to the public by the media in predominantly negative terms, with a heavy and repetitive emphasis on words such as ‘carnage’ and ‘incompetence’. Indeed, if people in Britain and the Commonwealth ever pause to reflect upon the 1916 experience, it is highly likely that their thoughts – influenced by a vaguely defined collective folk-memory of the Somme – will have turned towards the slaughter of the Pals battalions, ‘lions led by donkeys’, ‘butchers and bunglers’, a ‘lost generation’, inadequate weapons, misguided strategy and tactics, drawn blinds in countless streets in the industrial North-West, in Belfast and on Tyneside, and, not least, the death of innocence and idealism on the blood-soaked fields of Picardy.But is that deeply rooted public perception of the Somme wholly justified or, alternatively, did the BEF – from Haig and GHQ down to divisions, brigades, battalions and batteries – actually learn and apply the lessons of the Somme battle? Did the BEF make organisational changes and adopt new tactics and techniques as a result of the Somme experience and, if so, did these changes and new tactics lead to an overall improvement in fighting methods and battlefield performance and thereby contribute significantly to eventual victory in 1918? In other words, can one detect a learning process in the BEF which either started during, or was accelerated by, the Somme offensive? In order to answer some, or all, of these basic questions, it might first be helpful to examine the nature and content of the historical debate on such issues as it was conducted between the early 1920s and the mid-1980s. One will then try to show how, over the last twenty years or so, modern scholarship and archive-based research has not only widened and deepened our knowledge and understanding of the command, operations and infrastructure of the BEF in the First World War but has also simultaneously begun to alter the whole tone of the debate for the better, even if there is still a long road to travel in that direction. - eBook - ePub

The Road to St. Julien

The Letters of a Stretcher-Bearer of the Great War

- William St. Clair, John St. Clair(Authors)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Leo Cooper(Publisher)

Chapter Eight1916 The Battle of the Somme

Any hopes still harboured by the governments of the belligerent nations, that there might be an easy route to victory in the European War, died in 1915. Despite defeat after defeat, Russia was still in the war, and that meant for Germany the strain of a war on two fronts – the old nightmare of Bismarck. But at least, from the German point of view, it was the German Army that was in the forward positions, holding most of Belgium and parts of France. The British and the French had no such comfort. If their failure in Artois and Champagne was not to be repeated, the scale of the military commitment on the Western Front would have to be enormous. With all the luck in the world, dislodging millions of dug-in Germans could not be done except at terrible cost in men’s lives. Escalation to all-out land warfare on the Continent of Europe appeared the only option. The alternative of using naval power in support of military operations in the east, as advocated by Churchill and Lloyd George, had been tried in 1915. It had ended in the ignominious disaster of the landings at Gallipoli. This failure of Churchill’s Dardanelles Campaign spelt victory for the so-called ‘Westerners’ in the British military establishment, those who thought that Britain’s military resources should be concentrated on the Western Front. And their victory was reflected almost immediately in changes in personnel in the Expeditionary Force. Churchill, having resigned in disgrace in November 1915 over Gallipoli, continued his descent by exiling himself to the Western Front to command a battalion of Scottish infantry, the 6th Royal Scots Fusiliers, of Willie’s 27 Brigade. General Haig, in contrast, became Commander-in- Chief of the Expeditionary Force in succession to Sir John French. - eBook - PDF

Pandora’s Box

A History of the First World War

- Jörn Leonhard, Patrick Camiller(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Belknap Press(Publisher)

Western Front, 1915–1917 388 | Wearing Down and Holding Out seventeen months of the war was the dominance of mechanized warfare and the war of materiel, with its heavy artillery and vast quantities of munitions. This lineup connected events at the front with the war economies of the home countries. The year 1916 gave the greatest impetus yet to mechanized warfare and the “battle of materiel”—and at the same time, with its high casualty fig-ures, showed the limits of any attempt to decide the war by means of large- scale frontal attacks. The battles of Verdun and the Somme shaped people’s vision of the western front and the collective imagination of the world war, and they have continued to do so down to the present day. Together, they accounted for an estimated total of 1.5 million dead, wounded, and missing. Each individual loss carried the reality of war into the societies of Britain, France, and Germany, but also of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and India. By the end of the year, there was scarcely one large family that did not number at least one casualty among its husbands, brothers, sons, or grandsons. Furthermore, the third year of war made it ever clearer how tightly the vari-ous theaters of war in Europe and beyond were intermeshed with one another. More than ever, the task was to redistribute resources, to redeploy troops when necessary to places where the danger was greatest. The link between Verdun and the Somme, the British aid to French troops, the Russian southeastern offensive to take some pressure off the Allies on the western front, the trans-fer of German troops from Verdun to the Somme, the German assistance to Austria-Hungary in Summer 1916 against the major Russian offensive under General Brusilov, the refusal of the German OHL in May and June to support the Austrian campaign against Italy in the Tyrol—all these marked the total context of the war. - eBook - PDF

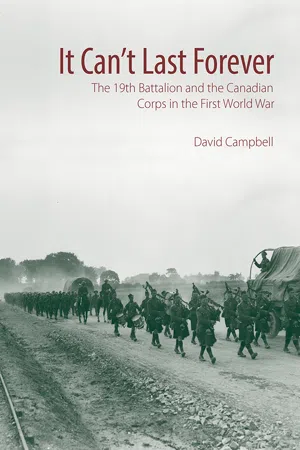

It Can't Last Forever

The 19th Battalion and the Canadian Corps in the First World War

- David Campbell(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Wilfrid Laurier University Press(Publisher)

175 9 Fighting at the Somme: 15 September– 3 October 1916 At precisely 6:24 am, the artillery barrage lifted from the German front line. With a blast of the officers’ whistles, the soldiers in the leading waves of the 4th Brigade leapt, crawled, or staggered to their feet and lurched forward over the smoking and pitted ground, adrenaline surging and every nerve firing at fever pitch. Although the instinct for self-preservation would push most men to run to the nearest bit of cover, it was difficult for them to move quickly, weighed down as most were with seventy pounds or more of arms and equipment. 1 Most of the troops advanced at a steady walking pace, with rifles and bayonets carried at the “high port.” Ten yards behind the first waves of each of the brigade’s three attacking battal-ions came the intermediate waves, consisting of platoons from the 19th Battalion, which were detailed to mop up the German front line and, beyond it, the Sunken Road. Ted Lang was among them in this, the battalion’s first great charge of the war. Recalling the event years later, Lang wrote: “We all got to our feet after the greatest artillery barrage of our guns up to that date, and ready for ‘death or glory’ [the motto of the 17th Lancers], we made a dash for the enemy trench, but Heinie had all he could take and up out of his trenches with hands held high and terror in his eyes they ran towards us in droves.” 2 While some 19th Battalion men, like Lang, continued forward on the heels of the first wave to occupy the German front 176 | Chapter 9 Map 6 – The Somme – Courcelette. Fighting at the Somme: 15 September–3 October 1916 | 177 line, others busily rounded up the dazed and terrified prisoners. One of Pte. John Mould’s friends, who went over the top that day, later claimed that he had never seen a finer sight in his life than he witnessed that morning.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.