History

Birth of a Nation

"Birth of a Nation" is a 1915 silent film directed by D.W. Griffith. It depicts the Civil War and Reconstruction era, portraying the Ku Klux Klan as heroes and African Americans in a negative light. The film was highly controversial for its racist portrayal of history and is considered a landmark in the history of American cinema.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Birth of a Nation"

- eBook - ePub

The Griffith Project, Volume 8

Films Produced in 1914-15

- Paolo Cherchi Usai(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- British Film Institute(Publisher)

The Moving Picture World (in its review by W. Stephen Bush) even mentioned the objectionable depiction of African Americans, and that only after a full page of praise for the film’s artistic and technical innovations. The exciting cinematic breakthrough that this film represented, evaluated by other writers in this volume, had an effect on 1915 audiences that cannot be overstated.Some of the overwhelming impact of The Birth of a Nation came, of course, from its timeliness: its production and release coincided with the semicentennial of the Civil War. For the previous four years this anniversary had increased Americans’ awareness of the war, an event still recent enough to reverberate in the national consciousness, but distant enough to ease some of the immediate bitterness that had followed in its aftermath. Between 1911 and 1915 the Civil War had become an increasingly persistent theme in American popular culture, not least in the work of filmmakers, including Griffith himself. The Birth of a Nation , with its vast, forceful and evocative summation of the war and Reconstruction, drew on that heightened awareness of the occasion and served as a culmination of it; audiences felt that the immense, disturbing collective experience of the crisis was being synthesized before their eyes. On 9 April 1915, the fiftieth anniversary of Lee’s surrender to Grant, the audience viewing The Birth of a Nation at New York’s Liberty Theatre stood in reverent silence as that event was reenacted on the screen.And then there was the racial content. That The Birth of a Nation is (inevitably, for a film based on The Clansman ) permeated with racist attitudes and riddled with offensive scenes can hardly be denied. The film’s historical preeminence has been a double-edged sword: racist material that would have been, and frequently was, ignored in lesser films became unavoidable in The Birth of a Nation because of its high profile. Today, of course, the effect is even more pronounced; the vast majority of 1915 films having been forgotten, Griffith and his film have become a lightning rod for all racism in early film. But what’s striking is that this racial content, so universally condemned today, elicited such a wide range of reactions in 1915. To the other distinctions of The Birth of a Nation - eBook - PDF

- J.E. Smyth(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Red Globe Press(Publisher)

2 Film History, Reconstruction, and Southern Legendary History in The Birth of a Nation David Culbert The timing was right: 1915 was the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the Civil War. D.W. Griffith’s notorious film masterpiece, The Birth of a Nation , purports to reveal the truth of America’s Civil War and Reconstruction from 1861 to 1877. The film is mostly set in a small town in the Piedmont part of South Carolina, although there are scenes which take place in Washington, DC, and a series of battles which purport to show some of the bitterest parts of the war, such as the burning of Atlanta or the final siege at Petersburg, Virginia. The film itself was shot entirely in California, so its geographical location is at best intended to suggest an approximate terrain. There are no loca-tion shots, although a number of scenes, such as the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, are taken—intertitles insist—directly from actual historic engravings or photographs. Griffith’s film has four claims on history. First, it is a brilliant piece of filmmaking, demonstrating the new medium of film deserved serious attention as an art form. Second, it is the lavish, feature-length film which transforms American cinema-going, showing distributors the possibility of tickets at previously undreamed-of prices, and in its commercial success suggesting an upscale audience largely untapped before 1915. Third, the film’s notorious racial stereotypes—and their seeming acceptance by most viewers at the time—suggest that the film, at a minimum, reflects widespread attitudes in white America about African Americans. Fourth, the film seems to present a Southern legendary view of the Civil War and Reconstruction, in which the Lost Cause is wedded to an assessment of Reconstruction as “the tragic era.” 1 The bibliography on The Birth of a Nation is unrivaled by that of any other feature film. Three recent books are of particular value. 11 - eBook - ePub

Critical Pedagogy, Race, and Media

Diversity and Inclusion in Higher Education Teaching

- Susan Flynn, Melanie A. Marotta, Susan Flynn, Melanie A. Marotta(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Django Unchained are highly contentious films. Both movies have been described as dangerous in some way, and both films examine issues of American enslavement, freedom, and white supremacism. From a pedagogic perspective, each text raises a number of interesting questions. These are the ways Western societies perceive questions of ‘race’ and national identity and the role that cinema plays in the circulation of these ideas and images.Lambasted and despised as the ‘most racist movie ever made’ (Rampell 2015 ), The Birth of a Nation remains an important part of Anglo-American film history. The film presents a skewered version of the after-effects of the American Civil War, Black emancipation, the abolition of slavery, and rise of the Ku Klux Klan. It demonises tolerance and integration, whilst celebrating the concept of racial purity. Yet, despite the ugliness of its racial politics, Birth is celebrated by film historians for its cinematic beauty, which is an outstanding and remarkable achievement of technology and scale. It is arguably the first blockbuster movie ever made and, as I suggest in ‘Re-Reading Birth of a Nation: European Contexts and the War Film,’ is also an early example of the ‘war film’ (Wright 2019 ). The power of the text lies in its ability to entice audiences to identify with its characters, even if they might not agree with the ideological beliefs proffered by them in the text. As McEwan argues, ‘If The Birth of a Nation had been a poorly made film that valorised the Klan, it would have been quickly forgotten and perhaps lost – at best it would be a minor historical curiosity’ (2015 , pp. 9–10). The endurance of this film comes not from its stance on race and segregation nor its dark vision of American society but from a future shaped by Aryan principles. It is remembered, and returned to, by film scholars because it ‘created a narrative structure and form recognisable in nearly every other historical epoch that Hollywood has produced since’ (McEwan 2015, p. 12). So, on the surface it might seem easier or more politically correct, to consign this film to the deepest recesses of cinematic memory. However, The Birth of a Nation tells students not just about how cinema has developed technologically, or about how the medium has grown in social and cultural significance over more than a century, but about what cinema can actually do - eBook - ePub

D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation

Art, culture and ethics in black and white

- Jenny Barrett, Douglas Field, Ian Scott, Jenny Barrett, Douglas Field, Ian Scott(Authors)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Manchester University Press(Publisher)

The Birth of a Nation shows no sign of disappearing, it seems that an impulse to understand this film and comprehend its influences has led to ever more revealing scholarship.Another function of observing a list such as that which follows is that we can note how often scholars took recourse to the metaphor found in the title of Griffith’s film by using the word ‘birth’. Griffith himself claimed that the choice of the film’s title, altered from The Clansman after early screenings, was that the film showed the birth of the American nation through the actions of the ‘Ku Klux Klans’ (Rogin, p. 152). Other accounts have the author of the source novel and play, Thomas Dixon, leaping to his feet at a screening declaring that Griffith’s version of his story should be called ‘The Birth of a Nation’ (see, for example, Cripps, 1963). Whether the name came from Griffith or Dixon, it initiated a theme in critical, cultural and creative deliberations. The Birth of Whiteness, for example, is the title given to Daniel Bernardi’s edited collection of 1996. Lary May’s 1980 monograph is titled: Screening Out the Past: The Birth of Mass Culture and the Motion Picture Industry, and Clyde Taylor’s chapter in Bernardi’s collection is titled ‘The Re-Birth of the Aesthetic in Cinema’. Just as Noble overtly responded to the title of Griffith’s film with his The Birth of a Race, performance artist DJ Spooky, aka Paul Miller, named his de/re-construction ReBirth of a Nation (2004). Recycling the birth metaphor invokes the film and its original implications as stated by Griffith and his supporters – that the film was telling the story of a nation’s origins. The common regard for Griffith has reinforced this sentiment by referring to him as the ‘Father of Film’ (Channel 4’s 1993 three-part series), who was responsible for the ‘birth of an art’, as claimed by James Agee in The Nation in 1948 after Griffith’s death (p. 264). Whether mindful or careless, there is an effort in this recycling of the notions of origins and fathering that establishes and re-establishes Birth as a beginning in our imaginations, with Griffith as its progenitor. Whether the film is viewed by writers as the beginning of American cinematic art and of Hollywood filming conventions, or of a public, mainstream denunciation of racial equality, or any number of other perspectives, the continued interest in The Birth of a Nation - eBook - PDF

Citizenship on Catfish Row

Race and Nation in American Popular Culture

- Geoffrey Galt Harpham(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- University of South Carolina Press(Publisher)

15 1 THE NATION IN THE Birth of a Nation Now I could see a chance to do this ride-to-the-rescue on a grand scale. Instead of saving one poor little Nell of the Plains, this ride would be to save a nation. —D. W. Griffith 1 For a film routinely described as the most controversial motion picture of all time, D. W. Griffith’s 1915 The Birth of a Nation has excited very little actual disagreement. An immense mass of scholarly research and critical commentary—surely more than that devoted to any film with the exception of Citizen Kane— has settled into a solid consensus on two views that exist in quiv- ering tension, neither complementing nor negating the other. First, Griffith’s three-hour epic represents the most impor- tant event in the early history of the medium, marking a sudden advance in terms of cinematic technique and narrative ambition over previous films, mostly one-reel nickelodeon entertainments shown in small theaters. So extraordinary and decisive was the break from previous practice that Griffith seemed almost to have invented cinema itself. On his death in 1948, James Agee de- scribed him as a “primitive tribal poet,” the most consequential 1. D. W. Griffith, “The Hollywood Gold Rush,” as told to Jim Hart, in The Man Who Invented Hollywood: The Autobiography of D. W. Griffith, ed. and annotated by James Hart (Louisville, KY: Touchstone Publishing Company, 1972), 89. CITIZENSHIP ON CATFISH ROW 16 figure in the history of film. “To watch his work,” Agee wrote, “is like being witness to the beginning of melody, or the first conscious use of the lever or the wheel . . . the birth of an art.” 2 In the course of creating modern cinematic narrative realism, Griffith introduced naturalistic acting to film and also created the concept of the director as a masterly creative force equal in stature to a composer, an author, a painter. - eBook - PDF

Ronald Reagan The Movie

And Other Episodes in Political Demonology

- Michael Rogin(Author)

- 1988(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

Dixon appealed to Wilson to see Birth. The president, who was not appearing in public because his wife had recently died, invited Dixon to show the film at the White House. This first movie screened at the White House swept Wilson off his feet. It is like writing history with light-ning, as Dixon reported the president's words, and my only regret is that it is all so terribly true. When the new National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and humanitarian social reformers tried to have Birth banned, Dixon used Wilson's endorsement to promote the film for months, before political pressures finally forced the president publicly to separate himself from the movie. The three southerners did not hold identical views of the meaning either of Birth or of the history to which it called attention. But they shared a common project. They offered The Birth of a Nation as the screen memory, in both meanings of that term, through which Americans were to under-stand their collective past and enact their future. 5 I Asked why he called his movie The Birth of a Nation, Griffith replied, Because it is. ... The Civil War was fought fifty years ago. But the real nation has only existed in the last fifteen or twenty years. . . . The Birth of a Nation began . . . with the Ku Klux Klans, and we have shown that. 6 Griffith appeared to be following Woodrow Wilson and Thomas Dixon and claiming that the Klan reunited America. But the Klan of Wilson's History and Griffith's movie flourished and died in the late 1860s. Griffith's real nation, as he labeled it in 1915, only existed in the last fifteen or twenty years. Dixon traced a line from the Klan to twentieth-century Progressivism, and Griffith may seem to be endorsing that view. But the floating it of Griffith's response made claims beyond those of Wilson and Dixon. It located the birth of the nation not in political events but in the movie. - eBook - PDF

Stagestruck Filmmaker

D. W. Griffith and the American Theatre

- David Mayer(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- University Of Iowa Press(Publisher)

Of all his films, and Griffith’s most ambitious to date, The Birth of a Nation (1915) drew most directly upon the theatre. Its plot and charac-ters were taken from Thomas Dixon’s play The Clansman , and the film’s overall structure and strategies—tactics to prepare, confound, and disrupt audience expectations—drew upon the ingrained conventions of Civil War and Reconstruction stage plays, not least those exploited by Dixon. To a lesser degree, The Birth of a Nation also echoed the the-atre’s role in debating ethnicity, race, and American identity. Griffith’s inheritance from the theatre was, seemingly, untroubled. There had been nothing in nineteenth-century Civil War and Recon-struction-era plays to unsettle audiences, nor had early-twentieth-century dramas of American identity elicited more than a mild sense of discomfort from their predominantly white spectators. If anything, these dramas reassured their audiences of the continuity of a com-fortable, unthreatening, white America. It was only when these two inherently stable theatrical genres were combined, first, by Thomas Dixon and more fully elaborated by Griffith that—rather like immers-ing magnesium in water—the violent hypergolic combustions that were The Clansman and The Birth of a Nation occurred. It is difficult, if not virtually impossible, from our twenty-first-century perspective, to understand the artistic and financial risks Grif-fith faced as he undertook to bring Dixon’s inflammatory and controversial play to the screen. It is equally difficult, given Griffith’s reluctance to discuss his choice of subject in other than flippant and casual terms, to understand the pressures and anxieties he experi-enced as he progressed. The Clansman was to provide Griffith with a secure frame in which to begin filming, but it also imposed a confin-ing structure from which he necessarily had to liberate himself in order to make a remarkable original work. - eBook - ePub

- Caron Knauer(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- ABC-CLIO(Publisher)

Chapter 9 The Birth of a Nation (2016) The Birth of a Nation (2016) tells the searing story of the mystical enslaved preacher, Nat Turner, leader of the 1831 bloodiest (though not largest) and most legendary slave rebellion in American history, which took place in Southampton County, Virginia. The actor Nate Parker (born in 1979) directed, starred in, wrote the screenplay, and cowrote the story with Jean Gianni Celestin. Parker cobbled myriad investors together, adding $100,000 of his own money to the film’s $10 million budget. The film debuted at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2016; a bidding war erupted after it garnered a deeply emotional response; the audience was “celebratory and euphoric. There was sobbing, cheering, and a sustained standing ovation” (Buchanan 2016). Hollywood was reeling from the second year there was a profound lack of nominations for people of color, #OscarsSoWhite. It won the Audience Award and the Grand Jury Prize (Buchanan 2016). Fox Searchlight paid a record-breaking $17.5 million and released the film on October 7, receiving sweeping press coverage, some of which about Parker was damning. Parker echoes the title of D. W. Griffiths’s notoriously racist but cinematically pathbreaking The Birth of a Nation (1915), based on the novel The Clansman by Thomas Dixon. Griffiths’s controversial film sparked protests at theaters and was banned in some cities. Set during Reconstruction (1865–77), a time when African Americans aced the political opportunities for representation they were finally given, the film was infused with anti-Black and white supremacy propaganda, depicting the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), the terrorist group, militating against African American accomplishments - eBook - ePub

- Barbara Lupack(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Cinema consolidated the very modernity of melodrama, making it relevant to a new age of national, not sectional, union. With Griffith’s “answer” to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a singularly popular melodrama of black and white became a serial phenomenon, asserting diametrically opposed forms of racial injury. Henceforth, in life or in fiction, no form of injury could seem innocent of racial motivation if blacks and whites were involved. Figure 2.1 Elsie Stoneman (Lillian Gish) is pursued by mulatto Silas Lynch (George Seigmann) (Birth of a Nation, 1915). Black Reactions to The Birth of a Nation The melodrama of black and white continued full speed ahead in mainstream American culture. Having leaped from novel and stage to silent film to sound film to television and most importantly into the “news,” comprising a 24-hour news cycle and an Internet-driven new media often fueled by citizen cell phones, it reaches into our contemporary moment. In this moment, it might seem that something like the perception of Tom suffering holds sway but only until the next O.J. Simpson comes along. Here, however, I would like to pause to consider the reactions of black people to the insult of The Birth of a Nation. By definition these were reactions that came from outside the mainstream. Melvyn Stokes has shown that by far the most prevalent reaction by blacks against Birth was that of the NAACP, which worked tirelessly to ban or at least cut some of the more egregious scenes from the film. Epic court battles ensued from city to city, with little success early in the film’s run and more success after World War I when the argument could be made that the film harmed the war effort and incited race hatred at a time when the nation needed unity (Stokes 229–31) - eBook - PDF

Uplift Cinema

The Emergence of African American Film and the Possibility of Black Modernity

- Allyson Nadia Field(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Duke University Press Books(Publisher)

He sums up the pos-sibilities: “They could ignore the film and its hateful portrayal, knowing not what damage it might do. They could urge censorship. Or, and least likely, they could finance and make their own films propagandizing favorably the role of Negroes in American life.”7 In the months following the release of The Birth of a Nation , Carl Laemmle and two employees of the Universal Film Manufactur-ing Company, Rose Janowitz and Elaine Sterne, began working on a response to Griffith’s film (eventually titled Lincoln’s Dream ) with the support of the naacp and, a little later on, the Tuskegeeans.8 Indeed, Black filmmakers (such as the Johnson brothers and Oscar Micheaux) would work throughout the fol-lowing years to counter the damage perpetrated by the film with films of their own. However, overshadowed by attention to the censorship battles and by the subsequent work of African American filmmakers was the immediate attempt to improve the film—in effect, to fix it—by incorporating an uplift film into screenings of the controversial epic. The New Era was one strategic response to the problem of prolific filmic racism. Along with debates about the need for Black filmmaking, this “least likely” solution was interwoven with the immedi-ate outcry against the filmic version of Thomas Dixon’s novel and stage play The Clansman .9 The idea of “answering film with film” to appease censors, calm protestors, and promote positive images of Black progress was an immediate reaction to The Birth of a Nation .10 The Birth of a Nation in Boston Hampton’s willingness to furnish its own moving pictures as an appendix to Griffith’s spectacle requires contextualization in the broader exhibition cir-cumstances of The Birth of a Nation , specifically with regard to its controver-sial appearance in Boston. - eBook - ePub

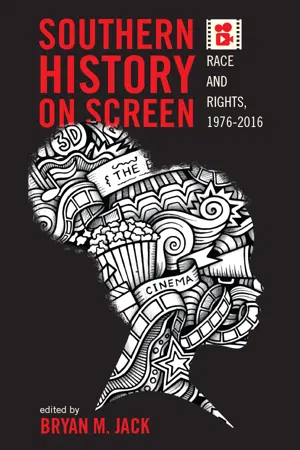

Southern History on Screen

Race and Rights, 1976-2016

- Bryan M. Jack(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- The University Press of Kentucky(Publisher)

true is profoundly troubling for the identity, self-identification, and Other-identification of black people and of the South in general, the more so since the Other have had little agency to challenge these mediatized stereotypes.Nate Parker and The Birth of a NationNate Parker’s The Birth of a Nation was initially celebrated as “instant rapture,” setting a sales record at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival.22 A belated corrective to #OscarsSoWhite, the film was conceived, written, and performed by a black director and leading actor and portrays the reimagining of Nat Turner’s 1831 slave rebellion against white slave owners and their families in Virginia. Parker presents his audience with a new perspective on African American slaves, who, through violent uprising, declared their autonomy and fought against the injustice of their enslaved circumstances rather than helplessly bearing the inhumanity and indignation of their victimization. His interpretation of this historical event, based on Nat Turner as a historical figure, thrusts the power of black masculinity into the spotlight.What Parker brings to the table is the idea of profoundly revising master narratives, a history largely written from a white perspective, both in literature and in film. His film connects the deep undercurrent of racism in America’s past to the pervasive effects of institutionalized racism in society today. The scene in which a young Nat Turner’s father is confronted by a group of murderous slave hunters, for example, is a readily accessible and visual approximation of contemporary police shootings of black men.23 In this context, Parker argues that Nat Turner’s story is about “one person who stood against a system that was oppressing people. And if we can relate to that in 2016, we must ask ourselves, what are we willing to sacrifice for what we want our children, and our children’s children, to enjoy?”24 The contemporary The Birth of a Nation is one salient answer to the call for provocative cinema, offering highly topical subject matter. It also sparked considerable public dialogue about race and appeared to dovetail with the Black Lives Matter movement, in protest against, among other hot-button issues, police brutality and the decades-long rise of for-profit prisons, a judicial system that appears stacked against black communities, and the beginnings of the Klan’s rebirth in some southern states.25

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.