History

Flappers

Flappers were a generation of young Western women in the 1920s who defied traditional societal norms by embracing a more liberated lifestyle. They were known for their short hair, stylish fashion, and rejection of conventional gender roles. Flappers symbolized a shift towards greater independence and freedom for women during the Roaring Twenties.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Flappers"

- eBook - PDF

Dry Manhattan

Prohibition in New York City

- Michael A. Lerner, Michael A. LERNER(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Harvard University Press(Publisher)

3 Frances French’s beaded handbag, Claire Fiance’s bobbed hair, the women’s brazen defiance of the Eighteenth Amendment, and the jaunty self-assuredness they both demonstrated in their encounters with the law were indications that they belonged to the new generation of young, head-strong women whose fashions and unrestrained behavior captured the imagination of the American public in the 1920s. In some of the numerous articles printed about them in American magazines and journals, these “flappers” were noted for their economic independence, their disregard for traditional gender roles, and their penchant for “shaking off the shreds and patches of their age old servitude.” In an article in the New Republic, Bruce Bliven wrote admiringly that the flappers of the Jazz Age were “highly re-solved that they are just as good as men, and intend to be treated so.” He added, “They don’t mean to have any more unwanted children. They don’t intend to be debarred from any profession or occupation which they choose to enter. They clearly mean . . . that in the great game of sexual se-lection they shall no longer be forced to play the role, simulated or real, of helpless quarry.” 4 As part of her independent and unconventional nature, the flapper of the 1920s also developed a taste for alcohol, and the cocktail became a mo-tif as central in her popular depiction as bobbed hair, short skirts, and rolled stockings. So vital was the cocktail to the experience of 1920s urban women that even beauty parlors and dress boutiques were expected to dis-pense alcohol to their female clients. One woman commented on the trend, “A nice place! A girl goes for a manicure and gets a nip, goes for a wave and I Represent the Women of America! ◆ 173 - eBook - PDF

Tomboys

A Literary and Cultural History

- Michelle Ann Abate(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Temple University Press(Publisher)

The Tomboy Shif ts From Feminist to Flapper / 121 during the 1920s. Before long, the colloquial term “flapper,” previously used to refer to “a young girl in her late teens” who possessed a “flightiness or lack of decorum” (“flapper” 1008), came to connote this new type of rebellious female figure. While literary works like F. Scott Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise (1920), Anita Loos’s Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1925) and Percy Marks’s The Plastic Age (1924) showcased her, the nation’s burgeoning film industry also became an important locus of representation. As Patricia Erens has argued, the construction, dissemination and especially popularization of the flapper “was definitely related to the movies” (133). Indeed, more than a dozen films released during the decade contained this word in the title alone. 1 In light of the frequency of Flappers on the silver screen, a 1924 article aptly quipped, “You cannot find the word ‘flapper’ in the dictionary, but you can find it in nine out of ten comedies. Next to talk of breaking the Volstead Act I am convinced that the flapper is the most popular movie subject today” (quoted in S. Ross 1). While Flappers were infamous for their possession of hyper-feminine qualities like wearing short dresses and being flirtatious, they were simulta-neously known for being boyish and, frankly, even tomboyish. In an often-overlooked facet of this figure, many of the traits associated with Flappers were variations on this gender-bending code of female conduct. In words that are reminiscent of tomboyism, Ann Douglas has said of the shifting fashion sensibility among middle- and upper-class white women during the 1920s: “Waists and breasts disappeared: long hair was banished along with the old-fashioned corset. Frills were out, sport clothes, [and] crisp suits . . - eBook - ePub

The Twenties

Fords, Flappers & Fanatics

- George E. Mowry(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Barakaldo Books(Publisher)

Many defenders of the social status quo were aghast at the activities of the new woman and protested vigorously that they signaled the downfall of society. Most such people blamed the war for the revolution in the social code. But a more reasonable explanation lay probably in the new urbanism and the mass consumer society. At any rate, after the feminine revolution of the Twenties native culture was never again the same. The following documents attempt to indicate something of the nature of the vast changes made.30. THE FLAPPER

The “flapper,” as the young independently-minded woman of the early Twenties was called, was the subject of much discussion in the press, the pulpit, and periodicals. The following article, “Flapping Not Repented Of,” The New York Times , July 16, 1922, discusses the nature of this new feminine type. Reprinted by permission of The New York Times.OMAR SANG OF WINE, WOMEN, AND SONG WHEN THE WORLD WAS YOUNG enough to appreciate it, and children still willingly listened to fairy tales of Cinderella and Aladdin, a distant relative perchance of Omar himself. But the time came when the virtuously sophisticated world smiled indulgently at the parody of some witty person who changed the old saying to “Near Beer, Chickens, and Jazz.”...Then the war with its sundry excuses for self-sacrifice, bravery and courage—at least we, the future Flappers, had the sheer audacity to name our fondest hopes in this way—came upon us and surrounded us all about.Now with the peace slinking in through every loophole, we turn ourselves around to see just what has been happening. Peace. “Yes,” say we who won our freedom in the slippery paths of war. “Peace.” And the outcome of it all is the flapper....As an ex-flapper I’d like to say a word in her behalf. I who have tasted of the fruits of flappery and found them good—even nourishing—can look back and smile. The game was worth it.... A flapper lives on encouragement, and only because these sweet, innocent boys try to go her one better does she resort to more stringent methods....Of course a flapper is proud of her nerve—she is not even afraid of calling it by its right name. She is shameless, selfish and honest, but at the same time she considers these three attributes virtues. Why not? She takes a man’s point of view as her mother never could, and when she loses she is not afraid to admit defeat, whether it be a prime lover or $20 at auction. - eBook - PDF

Youth Culture in Modern Britain, c.1920-c.1970

From Ivory Tower to Global Movement - A New History

- David Fowler(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Red Globe Press(Publisher)

3 The Flapper Cult in Interwar Britain: Media Invention or the Spark that Ignited Girl Power? In Hollywood films of the 1920s, and in the short stories and novels of F. Scott Fitzgerald, the flapper is a cigarette-smoking, dance-mad young female in her teens to early twenties. Her hair is ‘bobbed’ or ‘shingled’ and neatly tucked under a cloche hat; a sort of helmet that clasped the head like a bathing hat. She wears knee-length skirts and make-up. She is the most iconic figure of the American ‘Roaring’ Twenties; and the symbol of teenage emancipation. 1 The classic Hollywood Flappers were Clara Bow, Colleen Moore and Louise Brooks; all very young actresses in their late teens to early twenties at their peak, who made era-defining films such as It (Clara Bow, 1927), Flaming Youth (Colleen Moore, 1923) and Pandora’s Box (Louise Brooks, 1927). 2 The movie flapper outlasted these iconic silent film actresses and survived into the new era of Hollywood musicals. In 1929, for example, a Super Cinema in Manchester screened the film ‘Movietone Follies of 1929’. It was advertised as a Hollywood musical about ‘Youth with a capital Y’ and featured a ‘Jazz-mad Flapper’ (played by Sue Carroll). It drew huge audiences and was screened at Manchester Hippodrome, a large city-centre cinema, for an unprecedented three-week period. 3 Much is known about the Hollywood Flappers of the 1920s. Clara Bow and Louise Brooks had only fleeting film careers. Clara Bow, the most famous of the flapper film stars of the Twenties, rose and fell from public approval before she passed her 25th birthday. She had emerged from an impoverished family in Brooklyn, New York, and by 1928 was receiving over 35,000 fan letters every month. But her Brooklyn accent was so strong that when the talkies came (in the late 1920s) she was unable to make the transition from silent films to talking films. Her private life also damaged her reputation. She was a flapper in reality as well as on screen. - eBook - ePub

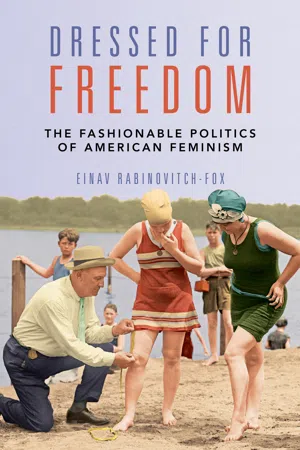

Dressed for Freedom

The Fashionable Politics of American Feminism

- Einav Rabinovitch-Fox(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- University of Illinois Press(Publisher)

95 For contemporaries, women’s fashions in the 1920s symbolized, for better or worse, a modern youth culture that sought a radical break with the past, and they used fashion as a conduit in their attempts to regulate this culture and shape its meanings.The thing that concerned the flapper’s critics the most was the moral implications of her fashion choices. The less clothes women wore, opponents claimed, the fewer moral values they retained.96 “The modern girl is extremist. She dresses in the lightest and most flimsy of fabrics. Her dancing is often of the most passionate nature, and I believe the modern dance has done much to break down standards of morals,” claimed the managing editor of the Pennsylvania Punch Bowl, a University of Pennsylvania magazine.97 For Barton W. Currie, the editor of the Ladies’ Home Journal, “flapperism” included all “modern manifestations” that had been associated with the “‘dreadful’ side of youth”: jazz, short skirts, bobbed hair, the “immodest” abandonment of corsets, cigarette smoking, petting parties, car riding, psychoanalysis, Greenwich Village follies, Ziegfeld chorus girls, one-piece bathing suits, modernism in art, birth control, eugenics, and Bolshevism.98 Others blamed the flapper’s short skirts for causing male office clerks to lose their morals and adopt improper behavior.99Black leaders were equally concerned about the flapper’s immorality.100 “One of the great problems we are facing today is immorality in our whole social structure. Modesty and kindred virtues have been thrown to the winds and not a few of our younger generation are allowing their baser natures to dominate,” a Chicago Defender editorial described some of the worries that leaders had regarding youth’s moral values.101 The boyish ideal of the flapper, which created a redefinition of female beauty and sexuality, proved to be challenging to those who emphasized Black women’s more traditional feminine traits. According to the Reverend J. Milton Waldron, pastor of Shiloh Baptist Institutional Church, bobbing one’s hair “cause[d] women to lose their feminine identity and destroy[ed] the personality and beauty of a woman.”102 - eBook - ePub

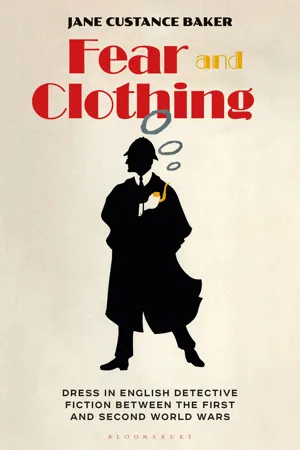

Fear and Clothing

Dress in English Detective Fiction between the First and Second World Wars

- Jane Custance Baker(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Visual Arts(Publisher)

Figure 5.2 A.A. Milne; Christopher Robin Milne – National Portrait Gallery. Popperfoto/Getty Images.Figure 5.3 Gabrielle Chanel, 1929. Hulton Deutsch Collection/Corbis via Getty Images.American media portrayed Flappers as very fast girls, who swore, smoked, wore the make-up hitherto reserved for the prostitute, showed their legs and danced wild American dances.35 However, the flapper was less obvious in British media and hardly a vamp.36 The social commentary The Long Week-End (1940) describes the flapper as the ‘girl pal’ who rides on the flapper seat of a motor bike and who was ‘comradely, sporting, and active’.37In this fiction, or in English films of the time, obvious female sexuality was rare.38 Dress patterns in magazines indicate that the British flapper was less dramatic, adopting a neat and tidy modern femininity.39 The modern fashions could be acquired, in different qualities by most classes of woman, as the cylindrical styles were easy to copy.40Flappers were conscientious, not overtly made up, except for Dulcie, though their elders may have thought any make-up is too much. Nor were they very overtly sexual. The response to the flapper, in detective fiction at least, was to allow the older characters, such as Hastings, who is describing the stage gymnast Dulcie in the opening quote, to display some shock and horror at her make-up and youth, but not enough to prevent him from appreciating her courage or marrying her.The First World War had a profound effect on women as well as men. For where some men had returned determined to avoid pre-war masculinity, over a million women experienced a very different and often exhilarating womanhood – being competent, stoic, brave, hard-working and strong in munitions factories, transport, the land, industry, nursing and the armed forces.41 Women knew fear, grief and death from enemy raids and munitions explosions but experienced pride and satisfaction in their war work too.42 - eBook - PDF

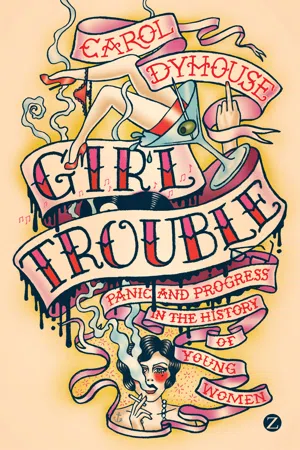

Girl Trouble

Panic and Progress in the History of Young Women

- Professor Carol Dyhouse(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Zed Books(Publisher)

In Britain between the world wars, just about everything thought characteristic of modern girlhood was subject to scrutiny and debate. The popular press was obsessed with the subject. 14 3.2 Pyjama-clad, cigarette-smoking flapper. Postcard image by the French artist Achille Lucien Mauzan, produced in 1918 in Milan. The stereotype of the flapper was widely recognisable (by kind permission of Gabriel Carnévalé-Mauzan). brAzen Flappers | 77 The appearance of the flapper or modern girl in the 1920s was distinctive in that it was a sharp break from Victorian and Edwardian tastes. Cropped hair shocked an earlier generation for whom long tresses had been a hallmark of femininity. In the nineteenth century, a range of rituals had grown up around hair brushing and hair care, and the moment when a young girl exchanged ribbons and braids for hairpins and ‘put up her hair’ was still an important rite of passage, signifying grown-up womanhood. Short hair – whether ‘shingled, bingled or bobbed’ – was widely interpreted as looking boyish, or as an act of out-right rebellion. 15 Parents might be horrified, and some girls were punished for cutting their hair. The future aviator Amy Johnson, aged eighteen, cut off her plaits and her father punished her by making her stay on for an extra year at school. 16 The artist and writer Kathleen Hale (author of Orlando the Marmalade Cat ) recorded that she narrowly missed being expelled from university for cutting her hair during the First World War. 17 Cosmetics were another bone of contention. Many Victorian ladies associated powder and paint with the dubious morals of streetwalkers, theatre and music hall performers. But after the war, young women turned to cosmetics with enthusiasm. 18 Lip rouge, powder puffs and kohl-rimmed eyes were the hallmarks of flapperdom. The more conservative were appalled, Baden-Powell among them. - eBook - ePub

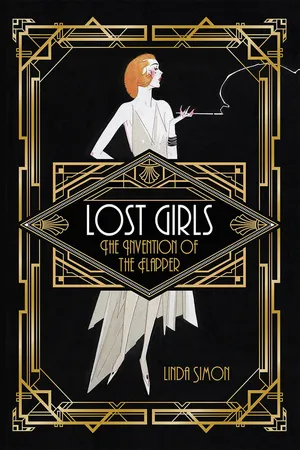

Lost Girls

The Invention of the Flapper

- Linda Simon, Linda Simon, Simon, Linda(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Reaktion Books(Publisher)

Outlook magazine in 1922, tried to explain her contemporaries to mystified adults who dismissed or disparaged them. ‘If one judges by appearances, I suppose I am a flapper,’ she admitted. ‘I am within the age limit. I wear bobbed hair, the badge of flapperhood. (And, oh, what a comfort it is!) I powder my nose. I wear fringed skirts and bright-colored sweaters, and scarfs’, and blouses with Peter Pan collars, which had not gone out of style since Maude Adams created her Peter Pan costume. ‘I adore to dance’, Page wrote:I spend a large amount of time in automobiles. I attend hops, and proms, and ball-games, and crew races, and other affairs at men’s colleges. But none the less some of the most thoroughbred superFlappers might blush to claim sistership or even remote relationship with such as I. I don’t use rouge, or lipstick, or pluck my eyebrows. I don’t smoke (I’ve tried it, and don’t like it), or drink, or tell ‘peppy stories.’ I don’t pet. And, most unpardonable infringement of all the rules and regulations of Flapperdom, I haven’t a line! But then – there are many degrees of flapper. There is the semi-flapper; the flapper; the superflapper. Each of these three main general divisions has its degrees of variation. I might possibly be placed somewhere in the middle of the first class.21That is, Page was more or less a semi-flapper, and more or less like any girl who had grown up in the 1910s.Nevertheless, Page conceded that the end of war, while it brought long-awaited relief, also generated disillusion, cynicism and disorientation that came to be associated with the flapper. ‘The war tore away our spiritual foundations and challenged our faith,’ Page wrote, appealing to parents to help her, and others like her, find their way. She pleaded with adults to stop criticizing Flappers, but instead ‘to appreciate our virtues’ and offer advice, guidance and understanding rather than the disdain that pervaded the media, even directed towards a wholesome, thoughtful girl like herself. - eBook - PDF

Aftershocks

Politics and Trauma in Britain, 1918-1931

- Susan Kingsley Kent(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

5 The fear of swamping in the rhetoric mobilized against the “flapper vote” suggested a concern about boundaries, that the lines separating men from women—or, more appropriately, masculine from feminine— had become less distinct and were liable to break down altogether. The anxiety about the blurring of gender lines grew out of the experi- ences of the Great War, during which the unprecedented opportunities made available to women by the war—their increased visibility in pub- lic life, their release from the private world of domesticity, their greater mobility—contrasted sharply with the conditions imposed on men at the front, where they were immobilized and rendered passive in a sub- terranean world of trenches, emasculated by the horrors they faced and their incapacity to do anything to alter their situation. The anxi- ety continued in the 1920s, as young women of virtually every class, instead of conforming to a role that assigned to them conventional attributes of self-abnegation, subservience, and motherhood, cut their hair, smoked cigarettes, drove fast cars, wore boyish clothing, danced wildly to a frightening new music associated with American negroes, and comported themselves generally without restraint. “Flappers” con- jured up images beyond those of the frivolous, boyish young woman of the jazz age: the term connoted contradictory meanings “of the female as androgyne, a figure characterised as sexless but libidinous; infantile 154 Aftershocks but precocious; self-sufficient but demographically, economically and socially superfluous; an emblem of modern time yet, at the same time, an incarnation of the eternal Eve.” 6 Worse still, their numbers, when added to those women voters over the age of 30, surpassed those of men, placing men—and the nation—in a precarious position. - eBook - PDF

Fashioning the Feminine

Representation and Women's Fashion from the Fin de Siècle to the Present

- Cheryl Buckley, Hilary Fawcett(Authors)

- 2001(Publication Date)

- I.B. Tauris(Publisher)

4 To Rowbotham and some feminist historians, ‘the cultural attitudes of the twenties and thirties were remote from those of the Victorian era. It was not so much a reaction; it was rather that anti-feminism took on new social and cultural forms.’ 5 In contrast, Sally Alexander sees the wide-spread engagement with the complexity of fashionable iconography by working-class as well as middle-class women, which perhaps distinguishes fashion in the 1920s and the 1930s from that of the preceding decade, as a mark of independence and as a characteristic of the search for a new sense of identity. 6 Her analysis points to the possibility of reading women’s fashion in the 1920s and 1930s afresh, refusing the dominant interpretation articulated by feminists writing in the 1930s, such as Winifred Holtby, who in Women and a Changing Civilisation argued: The post-war fashion for short skirts, bare knees, straight, simple chemise-like dresses, shorts and pyjamas for sports and summer wear, cropped hair and serviceable shoes is waging a defensive war against this powerful movement to reclothe the female form in swathing trails and frills and flounces to emphasise the difference between men and women. 7 In the context of the immense turmoil and insecurity generated by the First World War and by women’s successful demand for the vote, femininity came under intense scrutiny between the wars. On the one hand, it signified a peaceful, alternative way forward following the ultimate masculine folly of war. On the other hand, discussions around femininity raised anxieties about women’s roles as wives and mothers, and the price to be paid for their economic and personal independence, as well as foregrounding a host of issues about women’s sexual identity and their relationships with men and with each other. At the same time, what it meant to be a woman and to be feminine were fiercely debated within feminist organisations, and by writers and commentators of both sexes.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.