History

George McClellan

George McClellan was a Union general during the American Civil War known for his organizational skills and cautious approach to warfare. He was appointed as the general-in-chief of the Union Army but was criticized for his failure to decisively engage Confederate forces. McClellan's leadership style and strategic decisions have been the subject of historical debate and analysis.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "George McClellan"

- eBook - ePub

The Wikipedia Legends of the Civil War

The Incredible Stories of the 75 Most Fascinating Figures from the War Between the States

- (Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Skyhorse(Publisher)

George B. McClellan George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826–October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician. A graduate of West Point, McClellan served with distinction during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848), and later left the Army to work in railroads until the outbreak of the American Civil War (1861–1865). Early in the conflict, McClellan was appointed to the rank of major general and played an important role in raising a well-trained and organized army, which would become the Army of the Potomac in the Eastern Theater; he served a brief period (November 1861 to March 1862) as general-in-chief of the Union Army. McClellan organized and led the Union army in the Peninsula Campaign in southeastern Virginia from March through July 1862. It was the first large-scale offensive in the Eastern Theater. Making an amphibious clockwise turning movement around the Confederate Army in northern Virginia, McClellan’s forces turned west to move up the Virginia Peninsula, between the James and York Rivers, landing from the Chesapeake Bay, with the Confederate capital, Richmond, as their objective. Initially, McClellan was somewhat successful against General Joseph E. Johnston, but the emergence of General Robert E. Lee to command the Army of Northern Virginia turned the subsequent Seven Days Battles into a partial Union defeat. However, historians note that Lee’s victory was in many ways pyrrhic as he failed to destroy the Army of the Potomac and suffered a bloody repulse at Malvern Hill. Historian Stephan Sears in To the Gates of Richmond notes McClellan’s Army of the Potomac inflicted 20,204 losses while only sustaining 15,855 themselves. McClellan’s army would be withdrawn from the Peninsula in August 1862. Military theorist Emory Upton noted at the time that “The worst that could be said of the Peninsula campaign was that thus far it had not been successful - eBook - ePub

Conflict and Command

Civil War History Readers, Volume 1

- John T. Hubbell(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- The Kent State University Press(Publisher)

McClellan: A Vindication of the Military Career of General George B. McClellan: A Lawyer’s Brief (New York: The Neale Publishing Co., 1916).3 . For two critiques of the tremendous amount of attention historians have devoted to McClellan’s personality in particular, see Joseph L. Harsh, “On the McClellan-Go-Round,” Civil War History 19 (June 1973): 101–18, and Rowland, George B. McClellan and Civil War History, 45–75. For a prime example of the tendency of scholars of Civil War command relations to place a heavy emphasis on personalities, which goes so far as to explicitly employ psychoanalysis in its effort to explain McClellan, see Joseph T. Glatthaar, Partners in Command: The Relationships Between Leaders in the Civil War (New York: Free Press, 1994), esp. 237–42.4 . McClellan to Cameron, [Oct. 31, 1861], in Sears, ed., Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan, 115–18.5 . David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995), 318; Benjamin Wade to Zachariah Chandler, Oct. 8, 1861, Zachariah Chandler Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., container 1/reel 1. Depository hereafter cited as LC. McClellan’s report, Aug. 4, 1863, in U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols., plus index and atlas (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1880–1901), ser. 1, vol. 5: 35. Hereafter cited as OR; all references are to series 1 unless otherwise noted. Sears, George B. McClellan, 129; George B. McClellan, McClellan’s Own Story: The War for the Union, The Soldiers Who Fought It, The Civilians Who Directed It, and His Relations to It and to Them, ed. William C. Prime (New York: Charles L. Webster, 1887), 226–27; McClellan, Memorandum for the Consideration of His Excellency the President, submitted at his request, [Aug. 2, 1861], in Sears, ed., Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan, - eBook - ePub

The Richmond Campaign of 1862

The Peninsula and the Seven Days

- Gary W. Gallagher(Author)

- 2000(Publication Date)

- The University of North Carolina Press(Publisher)

39Within days McClellan was writing in the harshest of terms about the president, perhaps because Lincoln had named Henry W. Halleck general-in-chief without telling McClellan beforehand. All during July he quarreled with the administration, promising action and then explaining why he could not act. Lincoln was decidedly less understanding than six months earlier. Indeed, he had come to doubt that McClellan would fight no matter the availability of men and resources. The general’s letters, especially to his wife, reveal a man obsessed with his own place and problems, at once boastful and fatalistic. Perhaps a just God had placed Abraham Lincoln in authority only to test his good and faithful servant, George Brinton McClellan.40 The Army of the Potomac was ordered back to Washington in early August, and its commanding general’s last letter from Fort Monroe was replete with anger and self-pity. He would have been better advised to have adopted James Thurber’s credo: “Don’t look back in anger. Don’t look forward with fear. Look around you in awareness.”41NOTES

1. Stephen W. Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon (New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1988), xi–91, passim. Sears’s studies of McClellan are the place to begin an analysis of the general. Spirited defenses of McClellan, not entirely persuasive, are Thomas J. Rowland, George B. McClellan and Civil War History: In the Shadow of Grant and Sherman (Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1998); Joseph L. Harsh, “Lincoln’s Tarnished Brass: Conservative Strategies and the Attempt to Fight the Early Civil War as a Limited War,” in The Confederate High Command and Related Topics, ed. Roman J. Heleniak and Lawrence L. Hewitt (Shippensburg, Pa.: White Mane, 1990), 124–41; and Harsh, “On the McClellan-Go-Round,” Civil War History - eBook - PDF

Shapers of the Great Debate on the Civil War

A Biographical Dictionary

- Dan Monroe, Bruce Tap(Authors)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

After achieving a seemingly im- pressive victory at the battle of Rich Mountain (in fact, William S. Rosecrans was more responsible for Union victory), McClellan was sum- moned to Washington, where he replaced top commander Irvin McDow- ell after his defeat at the first battle of Manassas. The choice of McClellan was almost a foregone conclusion, as the dashing general now ranked sec- ond only to Winfield Scott in the regular army and had an excellent repu- tation from his service in the Mexican War. At age thirty-four, McClellan's rise to top command was remarkable, but the "Young Napoleon," as he was called, seemed confident, almost arro- gant, in his ability to get the job done. He threw himself energetically into reorganizing, refitting, and retraining the raw masses of recruits that swarmed the Washington camps. As an organizer and administrator, Mc- Clellan's talents were considerable. When impatient Northerners, particu- larly Republican congressmen, began to demand action, McClellan became defensive and critical. The haughty attitude of the military professional toward civilian leaders crept into his actions as well as his correspondence. Perhaps his most famous snubs were administered to President Abraham Lincoln. His contempt for his commander-in-chief is well documented, and throughout his correspondence, he repeatedly referred to Lincoln in deroga- tory ways, using such terms as the "original gorilla." On one occasion in the fall of 1861, McClellan went to bed after returning from an engage- ment, deliberately ignoring Lincoln, Secretary of State Seward, and Presi- dential Secretary John Hay, who were waiting at McClellan's headquarters to confer with the general. GEORGE BRINTON McCLELLAN 199 Had McClellan's private correspondence been destroyed, the historical picture of the general would be much more sympathetic. - Major-General Sir Frederick Maurice(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Golden Springs Publishing(Publisher)

Lincoln’s answer to the defeat of Bull Run was a call for 500,000 volunteers for three years, and an exercise of certain of his Presidential powers which caused many Senators and Congressmen to make wry faces. He also brought General McClellan from Western Virginia, where he had gained a substantial success, to command the troops around Washington. McClellan was then thirty-nine years old. He had been an officer of the Engineers in the United States Army and had served with credit on General Scott’s staff during the Mexican War. On leaving the army, he had been first chief engineer and then vice-president of the Central Illinois Railway. While in that position he had taken a keen interest in politics, and had been an active supporter of Douglas, Lincoln’s chief political opponent. This was one of the causes of his undoing. Not that there is the smallest evidence that McClellan’s political views ever influenced Lincoln’s attitude towards his general, but it did not make McClellan very favorably disposed towards Lincoln, and it was the cause of suspicion and distrust in certain members of Lincoln’s entourage. Thus there were, from the first, seeds of trouble which quickly germinated and grew.McClellan was undoubtedly a good soldier. Lee after the war declared that of the Union generals the ablest was “McClellan by long odds”;{45} but Lee knew McClellan only as an opponent. Grant also after the war declared: “If McClellan had gone into war as Sherman, Thomas, or Meade, had fought his way along and up, I have no reason to suppose he would not have won as high distinction as any of us.”{46} Grant had opportunity of knowing of McClellan’s performances both as a commander of troops in the field and as a commander-in-chief in relations with a Government, and his judgment is probably the more correct of the two.When McClellan was brought to Washington he was a young man of attractive manner and appearance; he had real gifts of organization and leadership, and was quickly not only respected but loved by his men. He became the idol of the press, which dubbed him the “Young Napoleon” — a nickname not without reference to his habit of issuing somewhat flamboyant proclamations to his troops. Everyone from the President downwards was anxious to serve and help him. As he wrote to his wife, “I find myself in a most strange position here, President, Cabinet, General Scott, all deferring to me. By some strange operation of magic I seem to have become a power in the land.”{47} In October General Scott resigned, and Lincoln made McClellan Commander-in-Chief. All this seems to have turned the General’s head. He was lacking in the elements of courtesy to the President, of whom the best he could say was, “He is honest and means well,”{48} while admitting that Lincoln had gone out of his way to be civil to him. After the first enthusiasm for him had cooled there was a good deal of political intriguing against him, and McClellan, finding the difficulties which he had himself in great measure created becoming too much for him, classed, in his anger, all the administration in Washington as “unscrupulous and false.”{49}- eBook - PDF

Why Veterans Run

Military Service in American Presidential Elections, 1789-2016

- Jeremy M. Teigen(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Temple University Press(Publisher)

McClellan was a bright, second-in-his-class cadet at West Point and notable among its graduates for having entered near his sixteenth birth-day and finished at age twenty. His first combat experiences happened the same year he graduated when he went to Mexico with the army. He had sought a command role but found that the slots were already full. He used connections to try to get a leadership spot in one of the fighting regi-ments, but he bitterly blamed the Polk administration for allowing politi-cal appointments to fill those spots rather than choose him. He remained in the engineer company for the Battle of Vera Cruz and was exposed to fire during the city’s siege. He and his men were scouting to build tempo-rary roads, and the city’s defenders took shots at them, which McClellan described as “whistling like hail around me.” 18 McClellan found himself in the middle of what would be a typical problem for this era when political alignments were palpable among offi-cers. McClellan served under General Gideon Pillow, an ally of President Polk from Tennessee, who in turn served under General Winfield Scott, a 18. McClellan and Myers 1917, 56. Civil War Generals and the Bloody Shirt 107 devout Whig who had previously sought the presidency. Historians have rated Pillow’s military skills below his political ones, and he and Scott shared no affection. Scott accused Pillow of exaggerating his role in victo-ries in his official reports and denying credit to those who deserved credit, including himself. The matter would later play out in courts-martial for all involved, but the feud was problematic during the war. McClellan saw firsthand how Scott had deployed his political rival to a less important part of the fight. Scott’s “battle plan had been designed to pacify the pres-ident’s friend and keep him occupied.” 19 In the Civil War, McClellan engaged in well-known clashes with Pres-ident Lincoln over the speed and cautiousness with which he commanded the Army of the Potomac. - eBook - PDF

An American Democrat

The Recollections of Perry Belmont

- Perry Belmont(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Columbia University Press(Publisher)

Nor did this view appear after the war. When the Southern Army was passing into Mary-land to invade the North, a dispatch was handed to General Lee. The reading of it cast an evident shadow upon his spirits, and General Longstreet asked anxiously, What is the news? The worst in the world, was the reply. McClellan is in command again. There could be no finer eulogy than this. When, in 1863, McClellan had been superseded and our armies had suffered a series of defeats, Lincoln made overtures to McClellan through Thurlow Weed. A great war meeting was arranged in one of the New York parks and McClellan was 1 5 Comte de Paris, History of the Civil War in America (4 vols., 1875-88), II, 356. The Comte de Paris was the grandson of Louis Philippe; after the death of his cousin the Comte de Chambord, he became the head of the family. His book on our Civil War has been regarded by our military authorities as an im-partial and valuable contribution to military history. He also wrote articles in the Revue des Deux Mondes, and published several books on labor. Frothingham considers him a first-rate authority. The Democratic Party and the Civil War 121 invited to preside. In his letter of declination, he wrote to Weed: I fully concur with you in the conviction that an honorable peace is not now possible, and that the war must be prosecuted to save the Union and the government at whatever cost of time, treasure and blood. I am clear in the conviction that the policy governing the con-duct of the war should be one looking not only for military success, but also to ultimate reunion, and that it should consequently be such as to preserve the rights of all union-loving citizens wherever they may be, as far as compatible with military necessity. - eBook - ePub

The Maryland Campaign of September 1862, Volume I

South Mountain

- Ezra Carman, Thomas G. Clemens(Authors)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Savas Beatie(Publisher)

In the cabinet meeting of the 2nd of September, the whole subject was freely discussed. The Secretary of War disclaimed any responsibility for the action taken, saying that the order to McClellan was given directly by the President, and that General Halleck considered himself relieved from responsibility by it, although he acquiesced and approved the order. He thought that McClellan was now in a position where he could shirk all responsibility, shielding himself under the President. Mr. Lincoln took a different view of the transaction, saying that he considered General Halleck as much in command of the army as ever, and that General McClellan had been charged with special functions, to command the troops for the defense of Washington, and that he placed him there because he could see no one who could do so well the work required. 11 The writers quoted other reasons for President Lincoln’s actions: It was not alone for his undoubted talents as an organizer and drill-master that he was restored to his command. It was a time of gloom and doubt in the political as well as the military situation. The factious spirit was stronger among the politicians and the press of the Democratic party than at any other time during the war. Not only in the States of the border, but in many Northern States, there were signs of sullen discontent among a large body of the people that could not escape the notice of a statesman so vigilant as Lincoln. It was of the greatest importance, not only in the interest of recruiting, but also in the interest of that wider support which a popular Government requires from the general body of its citizens, that causes of offense against any large portion of the community should be sedulously avoided by those in power. General McClellan had made himself the leader of the Democratic party. Mr - Available until 22 Apr |Learn more

The Civil War Generals

Comrades, Peers, Rivals?In Their Own Words

- Robert Girardi(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Zenith Press(Publisher)

Ohio in the War , 1:308, 309“McClellan is not the man to make himself popular with the masses. His manners are reserved and retiring. He was not popular either in Chicago or Cincinnati, when at the head of large railroad interests. He has never studied or practiced the art of pleasing, and indeed has not paid attention to it which every man whose position is dependent on popular favor must pay, if he expects to retain his position.” —George G. Meade, Life and Letters , 1:253“Before this reaches you, you will have read of the removal of McClellan. God be praised that this act of justice to the army and the country, so long delayed, has been consummated at last. It is better to the country than a decisive victory over the enemy. Indeed, I am not sure that it is in itself a decisive victory over rebels at home.” —James A. Garfield, The Wild Life of the Army , p. 176“I consider him one of the weakest and most timid generals that ever led an army. This opinion is held by General Hooker and nearly every prominent one of his field marshals … He is constantly scheming in politics, and I think the Government would at once remove him but for the fear that it would strengthen the Democratic party too much in the coming election … I have no hope for the success of our arms in the East till McClellan is removed entirely from active command.” —James A. Garfield, The Wild Life of the Army , p. 315JOHN A. MCCLERNAND Major general. Illinois Congressman. Veteran of Black Hawk War. Division and corps commander, Army of the Tennessee.“John A. McClernand … By profession a lawyer, he was in his first of military service. Brave, industrious, methodical, and of unquestioned cleverness, he was rapidly acquiring the art of war.” —Lew Wallace, Battles and Leaders - eBook - PDF

- G. Goethals(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

He had initially pleaded that the general in chief should be granted the “cordial support” without which he could not carry out his wide-ranging duties. He had always been skeptical of McClellan’s overconfident claim that “I can do it all,” that is, combine the position of commanding general with command of the Army of the Potomac simultaneously. This position was struc- turally unsound, and McClellan was overborn by its responsibilities. He failed to reassure the president, placate his many critics not just in the Congress but in the cabinet, too, and army command obscured the Brian Holden Reid 202 many successes achieved while he was general in chief for which he was not accorded any credit. In many ways, Lincoln agreed with these critics, and he had never been convinced by the peninsular concept, which involved turning Confederate defenses in Northern Virginia by an amphibious landing between the York and James Rivers, advancing on Richmond from the east. Yet he strove, despite McClellan’s self- defeating petulance, to support him. He had no choice, in many ways, for he had no other general to turn to. Yet McClellan gave no reason why he should trust him. Lincoln’s cabinet colleagues and staff seem to have been more annoyed than he was by McClellan’s insolent behavior. In one of his more insulting private references, he called Lincoln a “gorilla.” This remark is usually interpreted as an unflattering descrip- tion of the president’s appearance. “Gorilla” as a term of abuse became popular in the 1860s and imputes the threat of physical force in the absence of intelligence. Its use prompts the speculation that for all his arrogance, McClellan might have been rather frightened of Lincoln. Needless to say, he was peeved when Lincoln took away the position of commanding general from him as he set out for the peninsula. 34 Lincoln’s patience with McClellan may be connected with his scheme to make as much use of War Democrats as he could in running the war. - eBook - PDF

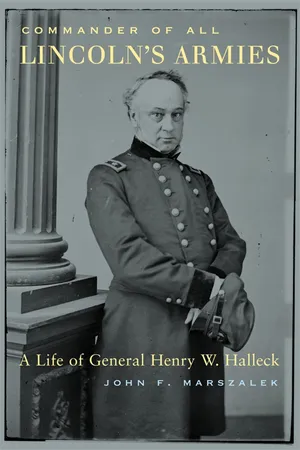

Commander of All Lincoln’s Armies

A Life of General Henry W. Halleck

- John F. Marszalek(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Belknap Press(Publisher)

Halleck, however, viewed his task from a different point of view, as being primarily administrative. As he had shown in his dealings with Grant, he believed that the only successful gen-eral was one who organized thoroughly. Union arms would only be victo-rious if paperwork flowed efficiently. He had demonstrated his greatest an-ger with subordinates not when they failed on the battlefield but when they Supreme Commander 135 violated some rule or regulation. He reigned with an iron fist when it came to army administration; military movements themselves were up to each general without Halleck’s or anyone else’s distant interference. He was not prepared to tell a subordinate general in the field that he should do or not do anything. It was up to that general to decide and then make sure Halleck knew what was happening. This was not what Lincoln had in mind. The President was under in-tense pressure from his cabinet to resolve the situation in Virginia. Chase, for example, called for “an immediate change in the command of the Army of the Potomac . . . [and the appointment of] a General in that com-mand who would cordially and efficiently” be cooperative. Consequently, the President told Halleck to see what he could do to solve the McClellan problem in Virginia. On the afternoon of July 24, therefore, accompanied by Ambrose Burnside, Halleck stepped aboard a steamship for the over-night trip to McClellan’s camp at Harrison’s Landing on Virginia’s James River. His physical bearing made a negative impression on at least one of those who saw him land. “I was greatly disappointed in his appearance,” this man noted. “Small and farmer-like he gives a rude shock to one’s pre-conceived notions of a great soldier.” Unlike McClellan, Halleck simply did not look like a man destined to lead men to victory on the battlefield.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.