History

Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Hiroshima and Nagasaki are two Japanese cities that were devastated by atomic bombings during World War II. On August 6, 1945, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, followed by another on Nagasaki on August 9, leading to unprecedented destruction and loss of life. These events marked the first and only use of nuclear weapons in warfare.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Hiroshima and Nagasaki"

- eBook - ePub

Reimagining Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Nuclear Humanities in the Post-Cold War

- N.A.J. Taylor, Robert Jacobs(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Introduction On Hiroshima becoming history N.A.J. Taylor and Robert Jacobs A great deal has been written about Hiroshima. 1 One only needs to mention the city’s name—Hiroshima—and people of all generations tend to recall the two nuclear attacks that America inflicted on Japan on August 6 and 9, 1945. Over time, however, there is also the growing tendency for the memory of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, along with the awareness of nuclear weapons and war in general, to fade from contemporary consciousness. Simply put, Hiroshima is becoming history. Nevertheless, for those who have retained a sense of the nuclear imaginary, Hiroshima has come to stand-in for a world historical event—and a crime against humanity—that called into question the very meaning of harm, as well as of life, death, and politics. 2 For the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were just that: attacks. Attacks not only on the human body, but also on the biosphere on which all life depends. In this way, both Hiroshima and Nagasaki introduced a form of harm that was fundamentally different-in-kind from all others that had gone before it. In 1999, prominent journalists in the United States were asked to vote on the top 25 news stories of the twentieth century. 3 When the results came in, the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Japan topped the poll. For many it was an important story because it was said to have “ended World War Two.” For others, it was because of the threat of the Cold War. Either way, the significance of the weapon was linked to its role in either an actual or potential nuclear war. 4 Throughout the last half of the twentieth century many people fixated on the threat of a global thermonuclear war during the Cold War, and when that threat was largely averted with the collapse of the former Soviet Union, the place of nuclear weapons in our imagined future became murky at best - No longer available |Learn more

Heritage and Tourism

Places, Imageries and the Digital Age

- Linde Egberts, Maria Alvarez, Linde Egberts, Maria Alvarez(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Amsterdam University Press(Publisher)

Post-war Hiroshima and Nagasaki After the 1945 bombings, Hiroshima and Nagasaki’s dif fering visions of reconstruction resulted in their having signif icantly dif ferent post-war urban identities as well (Diehl, 2014). Hiroshima’s municipal of fic ials HERITAGE LANDSCAPES OF Hiroshima and Nagasaki 59 decided that their city’s post-war identity would centre on its being the primary site of the atomic bombing by ratifying the Hiroshima Peace Commemoration City Construction Law in 1945. The law reflected not only the direction Hiroshima had taken since the bombing but also the image of fic ials wanted to project in the future: as the first city in the world to experience the devastation unleashed by the atomic bomb, Hiroshima would become the pre-eminent symbol of the horror of war and the impor-tance of peace. Among Japan’s bombed-out cities, Hiroshima managed to preserve its image as the sole “city of peace”. Beginning in the mid-1950s, it became the centre of all the country’s movements opposing nuclear weapons and promoting peace, whereas Nagasaki of fic ials continued to view the atomic bombing as a minor part of their city’s identity, reviv-ing, instead, its image and status as a cultural centre of international importance (Diehl, 2014). Thus, through these dif ferent narratives, the two cities illustrate dif ferent perspectives regarding the dropping of the atomic bomb and its aftermath. The debate over rebuilding the wasteland of post-bombardment Nagasaki encompassed multiple points of view (Diehl, 2014), and the dif ferent paths it took in comparison to Hiroshima, particularly during the first f ive years of reconstruction, have been the subject of scholarly study. - eBook - PDF

Hiroshima

The Origins of Global Memory Culture

- Ran Zwigenberg(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

4 Carol Gluck, “The Idea of Showa,” Deadalus 119, 3 (July 1990), pp. 12–13. 5 The quotation is from a visiting Nigerian journalist, James Boon, who told a Japanese col- league, “People built this city in order to forget about the bomb … [they] are trying really hard to live just like people in other cities.” Cited in the Yomiuri Shinbun, June 18, 1962. Hiroshima and the politics of commemoration 3 Because of the nature of the tragedy and the enormous importance given to the efforts to formulate a proper reply to it, the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki came to possess important symbolic power. The bomb- ing was thought to have bequeathed Hiroshima’s victims with a global mission and importance. This was synchronous with and influenced by a similar view of the place of the victim-witness in Holocaust discourse. In both discourses, the survivor was eventually elevated as the ultimate bearer of moral authority; what Avishai Margalit called “a moral wit- ness.” 6 This development was a direct consequence of the unprecedented nature of the tragedies and the failure of conventional means to represent and explain them. This had important implications for commemor- ation and politics in Japan and elsewhere, a phenomenon that went well beyond the confines of one nation or culture. As evidenced by Robert Lifton’s story, whose moment of shock in Hiroshima led him on to a car- eer that affected profoundly both cultures of memory, Hiroshima had an important role, now largely forgotten, in the making of global memory culture. However, the importance of Hiroshima was not appreciated by scholarship on either Hiroshima or the Holocaust so far. - eBook - ePub

Ways of Forgetting, Ways of Remembering

Japan in the Modern World

- John W. Dower(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- The New Press(Publisher)

The delayed timing of these first intense Japanese encounters with the human tragedy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had unanticipated consequences. For example, censorship began to be lifted at approximately the same time that the Tokyo war-crimes trials ended (December 1948). The culminating moments of the protracted Allied juridical campaign to impress Japanese with the enormity of their wartime transgressions thus coincided with the moment that many Japanese had their first encounters with detailed personal descriptions of the nuclear devastation that the Americans had visited upon them. While former Japanese leaders were being convicted of war crimes, sentenced to death, and hanged, the Japanese public simultaneously was beginning to learn the details of Hiroshima and Nagasaki for the first time. For many Japanese, there seemed an immoral equivalence here.Of even greater political consequence, the Japanese really confronted the horrors of nuclear war three years or more after Americans and other unoccupied peoples did—at a time when China was being won by the Communists, the Soviet Union was detonating its first bomb, hysteria in the United States had given rise to rhetoric about preventive war and preemptive strikes, runways all over occupied Japan and Okinawa were being lengthened to accommodate America’s biggest bombers, and, in short time, war came to Korea. In effect, the Japanese confronted the bombs and the most intense and threatening moments of the Cold War simultaneously. They did so, moreover, at a level of intimate concern with the human consequences of nuclear weapons that ran deeper than the generally superficial American impressions of a large mushroom cloud, ruined cityscapes, and vague numbers of abstract “casualties.”The impact of John Hersey’s classic text Hiroshima in the United States and Japan can be taken as a small example of the ramifications of this aberrant collapse of time. Hersey’s terse portraits of six victims of the Hiroshima bomb stunned American readers when first published in 1946. His account originally was written for the urbane New Yorker magazine, however, and reached a rather narrow upper-level stratum of the American public. By 1949, moreover, when anti-Communist hysteria had take possession of the American media, the initial impact of the book had eroded. By this time, Hersey’s masterwork had no conspicuous hold on the American mind. A Japanese translation of Hiroshima - eBook - ePub

Natural Disaster and Reconstruction in Asian Economies

A Global Synthesis of Shared Experiences

- Kenneth A. Loparo, Kenneth A. Loparo, Kinnia Yau Shuk-ting(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

literature and art, including novels, poetry, visual arts, and photogra phy that had previously been censored and now found a ready reception among publishers and readers, conveying with sensitivity, nuance, and pathos the nature of experiences that had the capacity to deeply move Japanese and international readers and viewers, often by understatement, or even silence. Two examples may illustrate the citizen literary and documentary response.To the Lost 30Yamada Kazuko When loquats bloom When peach blossoms in the peach mountain bloom When almonds are as big as the tip of the little finger My boys Please come. Nagai Kayano (5 at the time of bombing, recalled) My brother and I were in the mountain house in Koba. My mother came from Nagasaki with clothes. “Mom, did you bring Kaya-chan’s too?” I asked right away. My mother said, “Yes. I brought lots of Kaya-chan’s clothes, too,” and stroked my head. This was the last time that she stroked me.My mother said, “When there’s no air raid next, come down to Nagasaki again, okay?” And she left right away in a great hurry.31In much of the literature and memoir, as in the film, anime, photography, and painting, there is an immediacy of the human experience that transcends argument and debate and conveys powerful human emotions including deep sympathy for victims, many of them women and children (figure 6.8 ). In some can also be found a sense, rarely explicitly stated, of the inhumanity of the assailant.Firebombing and Atomic Bombing in Japanese and American Museums, Monuments, and MemoryFrom “Fire,” second of the Hiroshima Panels by Maruki Iri and Toshi.Figure 6.8National and local state governments everywhere wield important commemorative powers as one weapon in the nationalist arsenal through their ability to build and finance museums and monuments that guard public memory of critical historical events, yet their policies may also become the locus of public controversy.The story line here closely parallels that of literature and the arts. The high-profile atomic bomb memorial museums at Hiroshima and Nagasaki—funded initially primarily by prefectural and city governments but subsequently lavishly supported by Tokyo in building two enormous national memorial sites—have produced major sites of national commemoration, mourning, and public education in Japan. Indeed, not only are the memorial museums (notably Hiroshima) among the most important sites of Japan’s ubiquitous school education trips, they are also arguably the single largest international, particularly American, magnet for tourists. See http://www.pcf.city.hiroshima.jp/top_e.html and http://www1.city.nagasaki.nagasaki.jp/peace/english/abm/ . A 1994 Atomic Bomb Survivors’ Assistance Act set in motion the creation of national memorials, which opened on August 1, 2002, in Hiroshima and in July 2003 in Nagasaki. Its mission—“To pray for peace and pay tribute to the survivors. To collect and provide A-bomb-related information and materials, such as memoirs of the A-bombing” (http://www.hiro-tsuitokinenkan.go.jp/english/about/index.html ). This meant that, at least until recently, both memorial museums provided no contextualization of the bombing in light of the history of Japanese colonialism, the invasion of China and Southeast Asia, or questions of war atrocities such as the Nanjing Massacre or the comfort women. Their mission was understood to be that of giving voice to Japanese - eBook - ePub

Resurrecting Nagasaki

Reconstruction and the Formation of Atomic Narratives

- Chad R. Diehl(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Cornell University Press(Publisher)

In other words, just as city officials had done in 1947, the international past was being used to overwrite—or at least dilute—the memory of the bombing, but this time by celebrating a false history. 56 By 1948, Nagasaki and Hiroshima had settled into their individual paths of reconstruction, each professing the greater significance of their city’s atomic destruction and peace work. The first ever Peace Declaration (heiwa sengen) in 1948, which would become a staple of the anniversary ceremony of Nagasaki (as in Hiroshima), made no mention of Hiroshima. “Peace Starts from Nagasaki” and “No More Nagasakis” became the phrases that defined Nagasaki’s perception of itself and its role in establishing everlasting peace by virtue of its “world status.” 57 Furthermore, officials in each city considered their own tragedy as the cornerstone of world peace, but the term held different meaning for each. Hiroshima officials viewed their city as different from and, in terms of the emergence of the nuclear age, more significant than Nagasaki, because it was the first city in history to experience the destruction of an atomic bomb. Nagasaki officials, however, considered their atomic bombing as more significant precisely because it was the second and last atomic bombing, which meant that their atomic tragedy had ended the war. But the approach of Nagasaki officials and city planners to rebuild the city as a center of international trade, tourism, and culture made them appear less eager than Hiroshima to stress the horror of an atomic bomb and the necessity to work for world peace. FIGURE 1.3. Colonel Delnore with municipal and prefectural officials, including Mayor Ōhashi and Governor Sugiyama, at a cocktail party in the afternoon on December 30, 1948. Source: Victor E. Delnore Photograph Album, 1949, Victor E. Delnore Papers, Gordon W - eBook - ePub

- Martin V. Melosi(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

3Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the Aftermath

From Total War to Cold WarINTRODUCTION: FROM THE LAB TO THE FIELD

The atomic bomb ceased to be an idea and became a reality in 1945. It was conceived as a practical application of relentless probing into the inner workings of the atom, and forged by a collaboration of science and the state. The race to beat the Germans to the bomb united those in North America, Great Britain, and elsewhere in a singular cause. The use of the new weapon was another issue entirely. US officials made a decision in the heat of battle to up the ante in destructiveness and to quickly end the conflict that engulfed the world. Such a choice had impacts well beyond the fatal days in August when the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki became the first casualties of a new kind of total war. The bombings and their aftermath clearly redefined the execution of war itself and the definitions of vulnerability and security for all nations.TRINITY: THE GENIE OUT OF THE BOTTLE

Robert Oppenheimer was not sure, but he vaguely recalled some years later why he gave the first explosion of a nuclear device the code name Trinity. It was likely a line from a John Donne poem: “Batter my heart, three person’d God.” Yet, given his regard for Hinduism, the moniker could have signified the trinity of Brahma, the Creator; Vishnu, the Preserver; and Shiva, the Destroyer. Others suggested that Trinity referred to three bombs being constructed at the time, or that someone else other than Oppenheimer came up with the name.1 Whatever the reason, there was a sort of otherworldliness about this giant step in atomic history.Almost everything about the test of the plutonium (or implosion) bomb was imbued with portent. The desert location where the detonation took place was more than 200 miles south of Los Alamos on the Alamogordo Bombing Range. This ninety-mile site in the valley between the Rio Grande River and the Sierra Oscura mountains was called Jornada del Muerto—Journey of Death or Dead Man’s Way. The effort to ready the bomb for testing was an exhausting journey itself for the Los Alamos team. To relieve the tension of the work the scientists organized a betting pool on how big the blast might be, but its size and intensity caught everyone by surprise. General Groves in particular constantly worried about sabotage of the bomb and beefed up security before zero hour. He also feared that the very limited amounts of plutonium would be destroyed if the test failed, seriously delaying the mission of the Manhattan Project. To say the least, Washington, now in the throes of the Pacific War, anxiously awaited the results of the test.2 - eBook - ePub

Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Restrospect and Prospect

- Frank Barnaby, Douglas Holdstock(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Part I The Past Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The Bombings and their Aftermath

Passage contains an image

The Effects of the Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Frank BarnabyFrank Barnaby worked as a physicist at the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment, Aldermaston (1951–57). He was on the senior scientific staff, Medical Research Council and Lecturer at University College London from 1957 to 1967. He has been Executive Secretary of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs (1969–70), Director of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (1971–81), Guest Professor at the Free University, Amsterdam (1981–85) and Visiting Professor, Stassen Chair at the University of Minnesota (1985). He is currently a defence analyst and writer on military technology.His many books include: The Invisible Bomb, The Gaia Peace Atlas, The Automated Battlefield, Star Wars, Future Warfare, Verification Technologies, Man and the Atom, Nuclear Energy, and Prospect for Peace. He has published numerous articles on military technology and defence and disarmament issues in scientific journals, newspapers, and magazines.DOI: 10.4324/9781315036366-18:15 am – atomic bomb released – 43 seconds later, a flash – shock wave, craft careens – huge atomic cloud 9:00 am – cloud in sight – altitude more than 12,000 metresThis is an extract from the log-book of the Enola Gay, the B-29 bomber which dropped the atomic bomb which obliterated Hiroshima on 6 August 1945. At 11.02 a.m. on 9 August 1945 a second atomic bomb destroyed the city of Nagasaki.The Two Atomic Bombs

The atomic bomb exploded about 600 metres above the centre of the city with an explosive power equivalent to that of 12,000 tonnes of TNT. This huge explosion, more than a thousand times more powerful than the largest conventional bomb (called the earthquake bomb!), was obtained by the nuclear fission of a mere 700 grams of uranium-235, out of the 60 kilograms or so of uranium-235 in the atomic bomb, which was called ‘Little Boy’, an early example of the way names are used to make nuclear weapons sound less horrific and more acceptable. Little Boy was, by today’s standards, a crude device, nearly 3 metres in length and weighing about 4 tonnes. - eBook - PDF

British Nuclear Culture

Official and Unofficial Narratives in the Long 20th Century

- Jonathan Hogg(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Academic(Publisher)

Brighter than a thousand suns At 8.15 am on 6 August 1945, 600 metres above Hiroshima, Japan, an explosive device containing uranium-235 detonated, creating what later became rationalized as 16 kilotons of energy. Three days later on 9 August, a different ‘implosion’ device containing plutonium-239 exploded 500 metres above Nagasaki with an explosive yield of 21 kilotons. This convergence of scientific and military expertise initiated unprecedented levels of human violence and suffering, and devastation on a vast scale (Figure 3.1). The huge energy and heat caused by these weapons incinerated organic matter across huge swathes of land and caused metal structures to bend. Shortly after both blasts, firestorms started which decimated the cities further. For those people who survived the initial aftermath of the bombings, there followed the unknown danger of acute radiation poisoning, as radioactive fallout from the bombs fell to earth. In the longer term, Hibakusha – atom bomb survivors – would suffer an array of illnesses ranging from wounds with impaired healing to a range of cancers, decreased fertility and genetic mutation. Hibakusha would also suffer from a range of psychological disorders and would be ostracized from mainstream society in the years following 1945. 1 Between 150,000 and 246,000 women, children and men were killed by the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Controversy remains over the decision to target these two cities, with their large civilian populations. Unlike any other weapon created by humankind, atomic weapons created an unpredictable toxic, human and environmental legacy. 2 CHAPTER THREE Early Responses to the Bomb, 1945–1950 BRITISH NUCLEAR CULTURE 46 Testimony of Michie Hattori, fifteen years old when she survived the Nagasaki atomic bomb: ‘When the bomb exploded, it caught me standing in the entrance to the shelter, motioning for the pokey girls to come in. First came the light – the brightest light I have ever seen. - eBook - PDF

Terror and the Sublime in Art and Critical Theory

From Auschwitz to Hiroshima to September 11

- G. Ray(Author)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

our reason and moral freedom, in that mixture of pain and enjoyment so treasured by romantic sensibilities. But all that gives way to the acute desolation of man-made disaster: the staggering genocides and murderous holocausts we’ve perpetrated on ourselves. (And this would still be true, wouldn’t it, if “first nature” returned as the ultimate real, as the realization of our worst apocalyptic fears and temptations, in the form of an irrepara- bly degraded global ecological base, increasingly unable to support life due to cumulative human impacts?) Sixty years after Auschwitz and Hiroshima, our thoughts are still trying to recognize what happened. Attempts to understand the relation between these two place-names work under a taboo and have hardly begun. Let us deepen our gloss on Hiroshima by adding, and at the same time marking how difficult this will be, what we were not told at the time but by now should know. This first use of a nuclear weapon was executed without warning and with the aim of inflicting massive civilian death and suffering in a city which until then American strategists had deliberately preserved in an undamaged state, so that it could become a demonstration, the show piece of a new technology. This atrocity was not necessary—not to U.S. national survival, not to the defeat of fascism, not even to avoid an invasion of the Japanese main islands. Within a war machine that had already turned a systemic eye on the strategic domination of the postwar configuration, available alternatives to using the weapon against civilians were considered and expressly rejected. 2 What the demonstration was meant to demonstrate was the will to do, precisely, that. In the absence of unavoidable necessity, every justification for the quantum leap of a weapon without limits is spurious. Even in the context of a terrible war, this was terror, a genocidal atrocity: a crime against humanity, if such a thing exists at all. - Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Growth Growth Growth

Human History and the Planetary Catastrophe

- Julian Cobbing(Author)

- 2024(Publication Date)

- Mvusi Books(Publisher)

112 13. Hiroshima On 16 July 1945 a team of scientists reacted with astonishment, but also jubilation, to their successful detonation of the first atomic bomb in the US desert of New Mexico. The bomb was of special design and needed to be tested; the explosive substance was plutonium, element 94. Three and a half weeks later on 9 August 1945 a similar bomb was dropped on the city of Nagasaki in Japan: it killed around 40,000 people – men, women and children. Three days before the Nagasaki bombing, an alternative design bomb, based on uranium 235, had been dropped, untested (so confident were the scientists that it would work) on Hiroshima: it killed over 100,000 people. The two bombings finally persuaded the Japanese government to accept defeat in the Second World War. The months July and August 1945 have ever since divided human history into two eras: before and after the atomic bomb. Less than eight years later, in 1952, an even more powerful bomb was tested in the Pacific Ocean: the hydrogen bomb, with an explosive impact several hundred times that of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs. There are today twenty or thirty thousand of these devices, under the political direction of the US, Russia, Britain, France, China, India, Pakistan, and possibly North Korea. If they were ever to be used they would wipe out human civilization. Since 1952 threats that these weapons would be used have occurred at regular intervals. The missiles are ready to be fired at a few minutes’ notice, once the political orders have been given. Thus began an age of universal fear unlike what had gone before. The scientists involved in the development of these weapons faced criticisms. - No longer available |Learn more

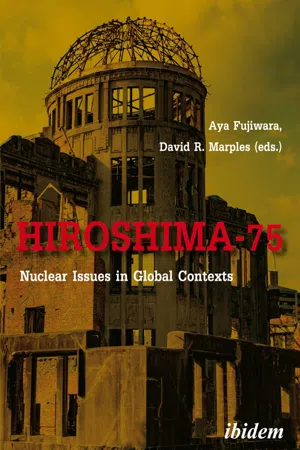

Hiroshima-75

Nuclear Issues in Global Contexts

- David Marples, Aya Fujiwara, David Marples, Aya Fujiwara(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Ibidem Press(Publisher)

1 These images attest to the strategies employed to dramatize the United States’ position in the world after its development of the atomic bomb, as well as the framework of influential narratives about this bomb.Synchronization between American History and World History

The content of Truman’s statement reflects how the US authorities wanted to portray the advent of the atomic bomb and their own conduct. It does not necessarily mean that everything that appears in the statement represents what really happened before and after the Hiroshima bombing. For instance, Truman’s statement does not mention that the actual targets of the bombing of Hiroshima were the commercial and residential districts in the densely-populated city centre. From March 1945, the US Forces had engaged in indiscriminate air strikes against large Japanese cities such as Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya, as well as medium-sized cities and even small villages across the Japanese archipelago. Earlier, they had already destroyed most functions of Japanese military operations. US attacks had destroyed about 400 Japanese cities and towns in the wake of indiscriminate air raids by the end of the war;2 the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were a prolongation of this extensive campaign against civilians.But Truman’s statement avoided mention of the entire development of these American military actions. This separation of the previous bombardment of other Japanese cities and towns from Hiroshima and Nagasaki at times generates a misleading view of the attack on the two southern cities as being isolated incidents, while forgetting and suppressing the memories of these other mass killings, which did not involve the atomic bomb, such as the Great Tokyo Air Raid of 9–10 March 1945. Although it is hardly conceivable that Truman’s statement was the main and singlehanded cause of the prevalence of this misleading view, his statement became the first instance of disconnecting these air raids before and after Hiroshima. Another aspect absent in Truman’s statement is any mention of the emittance of radiation, an invisible and deadly substance, from the atomic bomb at the moment of explosion. Instead, the statement puts a singular emphasis on its blast power. This lack of reference to radiation gives his description of the impact of the atomic bomb a lopsided nuance. I will return to this point later.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.