History

President Truman

President Truman, the 33rd President of the United States, served from 1945 to 1953. He is best known for making the decision to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, effectively ending World War II. Additionally, Truman implemented the Marshall Plan to aid in the reconstruction of Europe and played a key role in the founding of the United Nations.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "President Truman"

- Campbell Craig, Sergey S Radchenko(Authors)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Yale University Press(Publisher)

62 3 TRUMAN, THE BOMB, AND THE END OF WORLD WAR II Franklin Roosevelt made American foreign policy—if not mili-tary policy—during the Second World War in a manner that would have been familiar to the grand European statesmen of the nineteenth cen-tury. He relied heavily upon personal diplomacy with his two main adversaries, Churchill and Stalin, rather than formulating detailed ne-gotiating strategies with advisers and cabinet members. He kept his real convictions and plans, insofar as he actually had real convictions and plans, to himself, rather than submitting them to any kind of policy process in Washington. Roosevelt proceeded after December 7, 1941, under the assumption that he was the unquestioned leader of the coun-try, its sole representative in the cauldron of wartime international pol-itics so unfamiliar to most Americans. Such was his power and reputation in American politics that his regal domination over the nation’s destiny in World War II went almost entirely unchallenged until his death in April 1945. 1 His successor, Harry S. Truman, enjoyed no power or reputation in American politics to speak of when he assumed the presidency on April 12. He possessed no experience in foreign affairs at all. His inclination as a midwestern politician had been to express his own views and plans plainly, and yet at the same time he came into office deeply dependent upon the experiences and expertise of the advisers and cabinet members Roosevelt had often excluded from final policy making. 2 He was therefore neither able nor willing when he became president to assume the kind of personal control that Roosevelt had wielded easily over the direction of American foreign policy. This would have been one thing had Truman taken office in 1935, or 1955. But he became leader of the most powerful country on earth at the climax of the most devastating war the world had ever seen.- eBook - ePub

- Gerald M. Pomper(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

33 They deserve commendation as much for their political abilities as for their humanitarianism. In only a few months, Truman led the United States to reverse its traditional stance toward the world, garnered large resources for the new course of action, and won the support of both political parties and the general electorate. Politics, not simply good intentions, accomplished a daring and innovative foreign policy.The President and the PresidencyPresidential choices certainly reflect the personal characteristics and the governing style of the individual men, like Truman, who make them. Such decisions are also critically shaped by the institutional character of the office and the circumstances of their historical period. Truman exemplifies these relationships. He would later offer a pithy description of the job of the chief executive: “I sit here all day trying to persuade people to do the things they ought to have sense enough to do without my persuading them…. That’s all the powers of the President amount to.”34 His terse description was particularly appropriate to the Marshall Plan, a program clearly of benefit to the United States but one that required adroit use of the bounded powers of the president. It illustrates well “the tensions in the American system that exist between restraints deriving from the institutional framework on the one hand and programs of action and presidentially driven solutions on the other.”35Of course Truman did not bring the Marshall Plan to life by himself. He was neither its intellectual creator nor its sole political sire. A president is not a biblical prophet or a divine lawgiver, a single, all-powerful individual who delivers truth and justice to a receptive people. Rather, a president is a democratic politician who must take ideas, wherever found, and win consent from a contentious citizenry. That was Truman’s task—and his achievement.The presidency has been evaluated in very different ways in American history and scholarship. We often rank presidents according to their “greatness,” placing Washington, Lincoln, and the two Roosevelts at the top, with Buchanan and Harding at the bottom. We can describe the president’s powers in Woodrow Wilson’s expansive terms: “The president is at liberty, both in law and conscience, to be as big a man as he can be. His capacity will set the limit.”36 Or we can minimize them, in the words of James Lord Bryce, as “the same in kind as that which devolves on the chairman of a commercial company or the manager of a railway.”37 - eBook - ePub

The Presidential Character

Predicting Performance in the White House, With a Revised and Updated Foreword by George C. Edwards III

- James David Barber, James Barber(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Near the end of his Presidency Truman wrote his daughter that "Your dad will never be reckoned among the great. But you can be sure he did his level best and gave all he had to his country. There is an epitaph in Boothill Cemetery in Tombstone, Arizona, which reads, 'Here lies Jack Williams; he done his damndest.' What more can a person do?"Truman's main difficulties as President arose when he had to—or felt he had to—react swiftly to an external demand for decision, such as at his press conferences. The decision to drop the first atomic bomb and the decision to intervene militarily in Korea were of this type. In both cases he leapt over the first phases of his decision-making process and quickly reached a choice which involved, as it turned out, the direst consequences. But as he developed wider experience the great initiatives of his administration also emerged—the Truman Doctrine, the Marshall Plan, NATO, Point Four. Under his leadership, the policy of containing Communism by preventive military and economic shoring up of regions threatened by Soviet expansionism developed its positive thrust, particularly in Europe. This is not the place to go into what that eventually came to or how it all might have been different. From the perspective of the Presidency, Truman took massive initiatives at a time when such initiatives seemed unlikely, given the circumstances of his accession to the office, his own qualifications, and the condition of the country.Harry Truman liked to say that "When you're at the bottom you've got no place to go but up." In 1946, his fortunes dipped close to the wrong end of the barrel. After Roosevelt's death the country had rallied around him, as Americans do in a Presidential crisis. Then the Gallup poll gave him 87 percent approval—three percent higher than FDR's top rating. A year and half later, as the Congressional elections approached, Truman was down to 32 percent. The nation was in a surly mood. The war was over and people wanted to get on with the rich full life. Roosevelt was dead, Churchill turned out of office, the great crusade which had united the country—and suppressed all its ordinary conflicts—was done with. Yet what the people found was sky-rocketing inflation, black markets, continual strikes, meat shortages, quarrels among the armed services, firings at the top of the government, the housing shortage, fears about the new atomic bomb, partisan battles in Congress, and growing rifts among the wartime allies. The climate of expectations called for a time of reassurance and recovery, after all the sacrifice and moral uplift of the war. A large part of the public did not find Truman reassuring. He got it from all sides: both the Communists and the unions were against him, while the Republicans berated him for being soft on Communism and unions. Whatever was wrong with the Presidency, the Republicans, out of power since 1933, could claim it was none of their doing, and urge throwing the rascals out. As usual, these emotions focused on the man in the White House. The slogan "Had enough?" got a strong play. Pundits such as Walter Lippmann pronounced their solemn judgments: - eBook - PDF

Presidential Risk Behavior in Foreign Policy

Prudence or Peril?

- Kenneth A. Loparo, William A. Boettcher III(Authors)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

C H A P T E R T H R E E Truman Case Studies I. Introduction and Overview The Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union began during the Truman administration. The World War II alliance, cobbled together by the personal diplomacy of Franklin Roosevelt, fell apart as the victors squabbled over the postwar settlement. The tensions that emerged between Truman and Stalin during the Potsdam conference would result in disagreements over the composition of governments in almost every liberated area. The threat that held the allies together during the war was replaced by the perceived opportunity to reshape the world in one’s own image and secure access to economic resources and global markets. The decisions made by the Truman administration between 1945 and 1951 would shape U.S. foreign policy for the next 45 years. The three cases examined below trace the origins of the Cold War. 1 First in Iran and Greece and later in Korea, the Truman administration would contain and then attempt to roll back the communist “menace.” 2 In each of these cases, Truman and his advisers were confronted with deteriorating situations under seemingly novel circumstances.Truman was forced to bal- ance alliance and treaty commitments with U.S. interests and declining military power. His choice to move from cooperation to confrontation involved decisions with significant elements of risk. In each case, President Truman considered various levels of U.S. military intervention. Truman’s decision making in these cases is fairly well documented, providing an excellent opportunity for evaluating the hypotheses that compose the Risk Explanation Framework (REF). The Iran, Greece, and Korea case studies all follow the same structure. - eBook - PDF

American Presidential Statecraft

From Isolationism to Internationalism

- Ronald E. Powaski(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

It was characterized by the willingness of the United States to apply its economic, political, and military power in the defense of non-communist regimes, first in Europe, then in the Middle East, and afterward in East Asia and Latin America. As a consequence, the spread of communism was largely contained to the limits it had reached in 1950. But the price the United States and its allies would paid in lives and treasure in containing communism over the subsequent four decades of the Cold War proved to be very costly indeed. Nevertheless, it is primarily on the basis of Truman’s containment strategy, and the policies and institutions that he established to implement it, that his reputation as a great statesman rests. FOR FURTHER READING There is an abundance of Truman biographies. Among the best is Alonzo L. Hamby’s Man of the People: The Life of Harry S. Truman (1995), which demythologizes Truman, noting his achievements but also por- traying his shortcomings as well. The most popular of the biographies HARRY S. TRUMAN, JAMES BYRNES, AND HENRY WALLACE: THE US RESPONSE... 252 is David McCullough’s Truman (1992), which while very readable, is short on analysis. For an excellent overview and assessment of the major Truman biographies that have appeared since late in his presidency, see Sean J. Savage’s “Truman in Historical, Popular, and Political Memory,” in Daniel S. Margolies, ed., A Companion to Harry S. Truman (2012), 9–25. For Truman’s account of his presidency, see his Memoirs, Vol. 1: Year of Decisions. (1955) and Vol. 2: Years of Trial and Hope (1956). It should be read with more than the usual care regarding facts, dates, and interpretations. - eBook - PDF

- Stephen Hess, James P. Pfiffner(Authors)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Brookings Institution Press(Publisher)

Harry S. Truman I 945~ I 953 Harry S. Truman, a tidy man himself, was of-fended by Roosevelt's freewheeling style as an administrator. He believed that government should be orderly, that promoting rivalries between members of an admin-istration was disruptive, and that loyalty was the most important unifying principle for an administration. Truman's background was also a clear con-trast to Roosevelt's. He had spent most of his adult life in Missouri organ-ization politics and in the U.S. Senate, which limited his circle of acquain-tances and his knowledge of bureaucracy 1 It was his sense of order and loyalty, and his background in the Senate, that determined the way he would conduct the business of the presidency. In the words of Richard Neustadt, who was there, Truman's White House rather resembled a senatorial establishment writ large. 2 Just as Truman came between Roosevelt and Eisenhower, so his vision of running the gov-ernment lay halfway between the designed chaos of his predecessor and the structural purity of his successor. On assuming office after Roosevelt's death in 1945, Truman invited the members of his inherited cabinet to remain in their posts, but it did not take long for the new president to realize that he must have his own team. Within three months he had replaced six of the ten department heads. Ulti-mately, twenty-four men would serve as his cabinet officers. Four of the first half-dozen appointees were or had been members of Congress (only 36 CHAPTER 4 Harry S. Truman 37 three had been during Roosevelt's three-plus terms). Treasury Secretary Fred Vinson, a former congressman from Kentucky, proved to be a person of exceptional perception. But Truman's eye for talent was not always so sure. When Vinson was moved to the Supreme Court in 1946, the presi-dent replaced him with John Snyder, an orthodox banker without Vinson's breadth, who, like Postmaster General Robert Hannegan, was an old friend from Missouri. - eBook - PDF

- Stephen M. Griffin(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Harvard University Press(Publisher)

• 2 Truman and the Post-1945 Constitutional Order T HE BEGINNING of the Cold War was a watershed for U.S. foreign pol-icy. This is the period running roughly from Stalin’s speech in February 1946, appearing to promise a conflict with capitalism, to President Tru-man’s 1950 decision to intervene in Korea and massively expand the armed forces. 1 As summarized by historian George Herring, “the Tru-man administration in the short space of seven years carried out a veri-table revolution in U.S. foreign policy. It altered the assumptions behind national security policies, launched a wide range of global programs and commitments, and built new institutions to manage the nation’s bur-geoning international activities.” 2 This period has been extensively studied by historians, but there has been an absence, especially in general accounts, of assessment of the constitutional significance of epochal events such as the Truman Doctrine, the formation of NATO, and the Korea decision. 3 At the same time, historians have shown that officials were aware that the nature of the constitutional order was changing. 4 According to Michael Hogan’s insightful account, there was an unceasing debate, centered on fears of a coming “garrison state,” over the effect the new global responsibilities of the United States would have on American government and society. 5 How would the coming “long war” affect the Constitution? In this chapter, I will describe how political elites convinced them-selves, the government, and the public that the pre–Pearl Harbor con-stitutional order was inadequate to the challenging circumstances that the U.S. faced in the Cold War. From the point of view of the executive branch, questions of war powers had to be subordinated to the larger Truman and the Post-1945 Constitutional Order 53 objectives of that policy. - eBook - PDF

America since 1945

The American Moment

- Paul Levine, Harry Papasotiriou(Authors)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Red Globe Press(Publisher)

It is true that Truman was outraged in 1945 by the Soviet refusal to hold free elections in Poland, in violation of the Yalta agreements. Moreover, the Potsdam conference in July 1945 failed to settle the permanent status of Germany, indefinitely prolonging the occupa-tion arrangements of the four allied powers. Yet despite these tribulations, the Truman administration rapidly demobilized the American armed forces from 12.1 million men in 1945 to 3 million in 1946, 1.6 million in 1947 and 1.4 mil-lion in 1948. The nuclear armaments program was also slow – in March 1947 the United States had only 14 unassembled atomic bombs. This was hardly the military posture of a power preparing for conflict. A ship in calm waters in the open sea may drift for quite some time without danger. But if it approaches a reef, captain and crew must jump to their sta-tions and get the ship moving. The reef that mobilized the United States was the message by the British government in February 1947 that by April it would withdraw its troops from Greece and Turkey and leave the Greek government to deal with the Greek communist rebellion by its own devices, unless the United States moved into Britain’s place. With this message, Britain abdicated from its Great Power status and passed the torch to the United States. With great danger approaching, geopolitical clarity prevailed at once: the Truman administration adopted the policy of resisting the expansion of the Soviet sphere in Europe. Nonetheless, the new geopolitical orientation had to be presented in terms suitable to American exceptionalism in order to bring AMERICAN POLITICS FROM ROOSEVELT TO TRUMAN 21 American society along. In his address to the Congress on March 12, 1947, Truman announced that the United States would support free peoples resist-ing subjugation by armed minorities or outside pressure: this became known as the Truman Doctrine. - eBook - PDF

Great Men in the Second World War

The Rise and Fall of the Big Three

- Paul Dukes(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Academic(Publisher)

5 Potsdam: The Arrival of Truman and ‘A Critical Juncture’ Victory in Europe: Potsdam On 8 May 1945, a leader in The New York Times declared that ‘The evil power that unsheathed the sword has been destroyed. The greatest threat that has ever been directed against modern civilization exists no longer.’ ‘The myth of German invincibility’ had been overcome ‘by the armies and navies of the United Nations and by the millions of plain people who supported them on the home fronts’. Inevitably, however, some names stood out: ‘the indomitable Churchill, who roused Britain to her finest hour; Marshal Stalin, who turned the Nazi tide at the gates of his own capital’, President Roosevelt and General Eisenhower. The late president would have a special place for Americans as the first to proclaim that ‘Nazism represented a mortal threat to the United States’, who ‘beyond all others, aroused the moral forces of humanity and in their name united all the separate and sometimes divergent forces into the Grand Alliance of the United Nations’. The victory vindicated the fateful decision to concentrate on Europe, but now the ‘costly lessons’ learned in the course of the defeat of Germany had to be applied to the ongoing war against Japan. In particular, ‘an ill-prepared and premature landing’ in response to pressure for a ‘second front … would have been doomed to failure’. Moreover, no modern war could be won without airpower, but the nation ‘beaten in the air must eventually be beaten on the ground’. While the Japanese army was smaller and weaker than the German, ‘the individual Japanese is imbued with a religious fanaticism such as was shown only by the most insane Nazis’. Now, superiority must be built up for an ‘all-out effort’ in the Pacific. Many might feel that it Great Men in the Second World War 88 was time for others to take on the chief burden, but too many might be ‘basing overoptimistic hopes on a quick entry of the Soviets’. - Geir Lundestad(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Columbia University Press(Publisher)

24 An even more moderate version is presented by Lloyd Gardner and Walter LaFeber. They both certainly play down the Truman Doctrine and the Marshall Plan as turning points and argue that the preconditions for action had been set well before the spring of 1947. The assumptions on which American policies rested were the depression of the thirties, World War II, and a near half-century of distrust of Soviet Communism. In Gardner's phrase, the world view of the American political leadership was based on their night-mare-like memories of the depression, their newfound eco-nomic power, and the reality of a profound challenge seem-ingly centered in the Soviet Union. 25 The fact that the preconditions for action had been set does not, however, American Foreign Policy, 1945-1947 13 mean that the action itself had unfolded. Both Gardner and LaFeber, therefore, see this period as more of a developing process than Kolko and Alperovitz do. Revisionists all agree that the United States used various levers to further its foreign policy objectives. While there is fairly general agreement on the way in which eco-nomic instruments were brought to bear on the Soviet Union by the Truman administration, all possible nuances can be found in revisionist views on the role the atomic bomb played in American diplomacy at the end of World War II. 26 How do postrevisionists deal with the problem of the degree of activity shown by the United States in the 1945 to 1947 period? A rough conclusion is that again they adopt some kind of middle position between revisionists and tradi-tionalists, although this position may vary considerably in its details from historian to historian. With John Lewis Gaddis it is difficult to find any single one decisive point, be it the Truman Doctrine or the transi-tion from Roosevelt to Truman. The emphasis on gradual change found both with moderate traditionalists and moder-ate revisionists is even more pronounced with Gaddis.- eBook - PDF

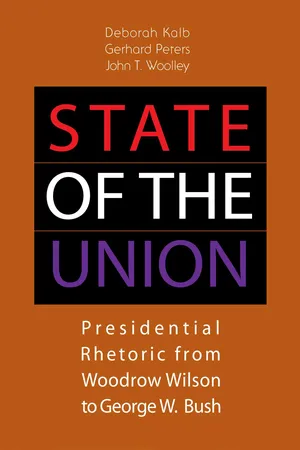

State of the Union

Presidential Rhetoric from Woodrow Wilson to George W. Bush

- Deborah Kalb, Gerhard Peters, John T. Woolley(Authors)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- CQ Press(Publisher)

“Above all, we have the vigor of free men in a free society. We have our liberties. And while we keep them, while we retain our democratic faith, the ultimate advantage in this hard competition lies with us, not with the communists.” M ESSAGE TO C ONGRESS ON THE S TATE OF THE U NION , J ANUARY 7, 1953 Harry S. Truman 1945–1953 346 Harry S. Truman, 1945–1949 Message to Congress on the State of the Union January 21, 1946 Harry Truman’s first State of the Union message came after an extremely eventful year. In the course of 1945, Franklin D. Roosevelt died, and World War II ended. The country faced a double transition: to a new president, Truman, and to a peace-time society. Truman’s written message, dated January 14 but released January 21, was lengthy; it combined the State of the Union and budget messages. In his message, the president discussed a wide range of issues, including the establishment—then under way—of the United Nations, postwar inflation at home, and labor strikes. Truman, a former senator from Missouri who had served as Roosevelt’s vice president for less than three months when Roosevelt died on April 12, found him-self leading a country that was concluding a monumental war. The war in Europe ended May 8, when Germany surrendered; the war in Asia concluded when Japan surrendered August 14, following Truman’s decision to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Truman signaled early in his presidency that he would continue the social reforms that Roosevelt had championed during the New Deal. On September 6, 1945, the new president outlined a twenty-one-point program, which came to be called the Fair Deal. It included an increase in the minimum wage, an extension of Social Security, and full employment; these themes were among those discussed in this State of the Union message.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.