Islamic Medicine

What Is Islamic Medicine?

Islamic medicine refers to the medical knowledge and practices developed during the Islamic Golden Age, primarily recorded in Arabic, the era's lingua franca. It was a multicultural synthesis, integrating traditional Arabian practices with Hellenistic, Indian, and Iranian medical systems(W.H. Vogel et al., 2009). While often called Arabic medicine, it reflects the contributions of diverse scholars across a vast geopolitical landscape connected by the Islamic faith rather than a single ethnic group (Bashar Saad et al., 2011).

Core Principles and Conceptual Foundations

The theoretical foundation of medieval Islamic medicine largely rested on the Greek humoral theory, where health required a balance of bodily fluids (W.H. Vogel et al., 2009). Alongside this scientific tradition existed Prophetic Medicine, a collection of health injunctions based on the sayings of Muhammad (Roy Porter et al., 2003). This religious approach emphasized hygiene and natural remedies like honey and cupping, though professional physicians typically prioritized the Greco-Arabic humoral framework for treating complex diseases (Roy Porter et al., 2003)(Deborah Brunton et al., 2013).

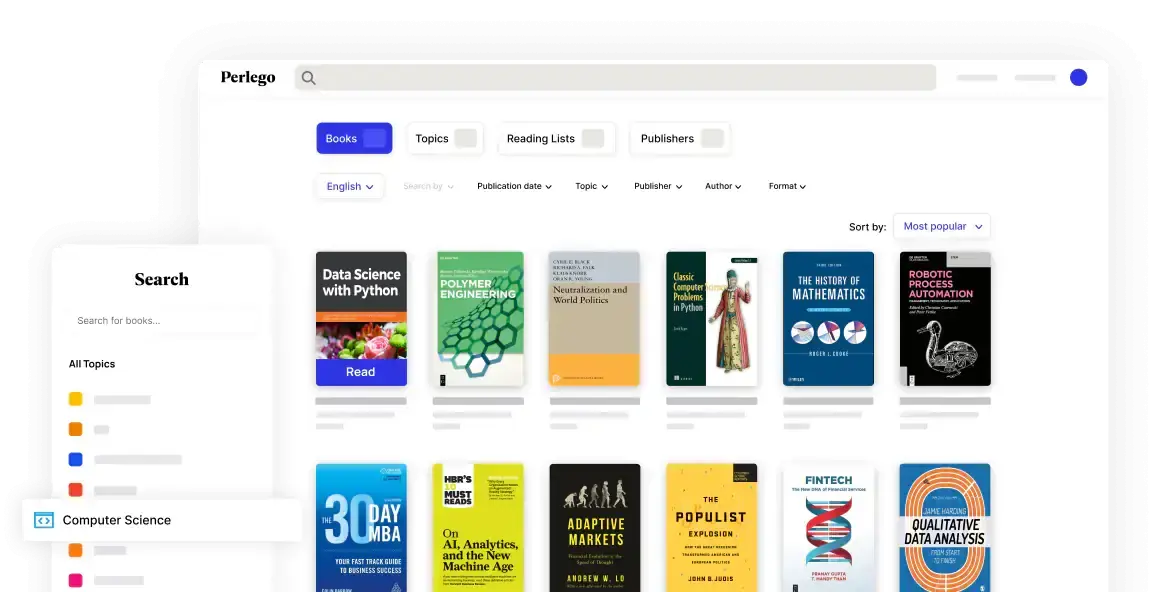

Your digital library for Islamic Medicine and History

Access a world of academic knowledge with tools designed to simplify your study and research.- Unlimited reading from 1.4M+ books

- Browse through 900+ topics and subtopics

- Read anywhere with the Perlego app

Historical Development and Key Figures

During the 9th century, Baghdad emerged as the premier medical hub of the Islamic world (W.H. Vogel et al., 2009). Renowned physicians like al-Razi and Ibn Sina produced encyclopedic works, such as The Canon of Medicine, which synthesized vast medical knowledge (Labeeb Ahmed Bsoul et al., 2018)(P Y Ho et al., 1997). The era also saw the institutionalization of healthcare through the creation of hospitals and the implementation of qualifying examinations for practitioners, raising the practice of medicine to a learned profession (P Y Ho et al., 1997)(Martin Levey et al., 2016).

Academic Significance and Global Influence

Islamic medicine significantly shaped global healthcare by preserving and expanding upon classical Greek and Roman texts. Latin translations of these Arabic works became the core curriculum in European medical schools for centuries (Bashar Saad et al., 2011)(P Y Ho et al., 1997). Furthermore, Muslim scholars made original advancements in specialized fields like ophthalmology, pharmacology, and surgery, transitioning medical study from theoretical observation to a discipline that combined theory with practical application and precise instrumentation (Labeeb Ahmed Bsoul et al., 2018)(Martin Levey et al., 2016).