History

Al Andalus

Al-Andalus refers to the Muslim-ruled Iberian Peninsula during the medieval period, from the 8th to the 15th century. It was a culturally rich and diverse region, known for its significant contributions to art, architecture, science, and philosophy. Al-Andalus was characterized by a unique blend of Islamic, Christian, and Jewish influences, and it played a pivotal role in the transmission of knowledge between the East and the West.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Al Andalus"

- eBook - ePub

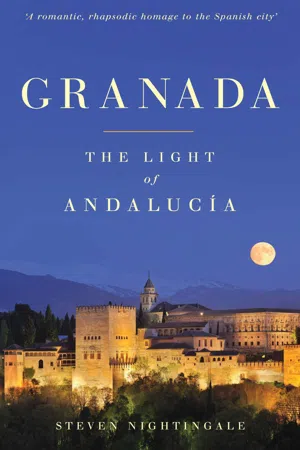

Granada

The Light of Andalucía

- Steven Nightingale(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Nicholas Brealey Publishing(Publisher)

Al-Andalus: Notes on a Hidden, Lustrous, Indispensable EraIN THE ALBAYZÍN, we lived face-to-face with the Middle Ages. The Alhambra, soaring on its promontory, had its beginning in the early 1200s. And our whole barrio had kept, through its thriving and catastrophe, the basic street pattern of a medieval village.Gabriella and I used to go whimsically about the lanes, sure that some of the ancient doors opened into another century. Sometimes we sat together before a wall of white plaster, where, as though watching a movie, we conjured the daily life of another epoch. Such fun gave us many laughs, as we rambled and whispered our way through the afternoon. But all these antics did not undo my wretched ignorance of the period.Let us define what we mean by Al-Andalus: it is the period of history spanning almost eight hundred years, from 711 to 1492, on the Iberian peninsula, under the administration of either Islamic emirs or caliphs, or Christian kings and queens. Whatever the faith of the powerful in whatever region of Iberia, Al-Andalus is a distinctive cultural space. When we arrived in Spain, I had studied the reign of Ferdinand and Isabel, their triumphant unification of Spain, and the explorations of Columbus. But I knew little about the Islamic, Christian, and Jewish leaders and even less about the scholars of the period.But the conjured movies and magic doors led me to shelves of books, and to the houses of our neighbors, and to the history of gardens and of our cherished neighborhood. And thence to the history of Al-Andalus.Just as the Albayzín is a study in unlikelihood, so the history of Al-Andalus is itself improbable; so improbable that, until recently, it hardly existed at all. Most of us learn something about medieval European history, but in general, the material covers in more depth the history of countries other than Spain. There is a simple reason for this: to study Christian Europe of the Middle Ages, you needed, principally, Latin, probably Greek, and the vernacular language of the region you studied. To study Al-Andalus, you needed not only Latin and medieval Spanish, but a mastery of Hebrew and Arabic, plus a willingness to understand the contributions of Arabic and Jewish culture. But scholars with such a sweep of languages and interests were rarely to be found, except in concept, like the saber-toothed tiger. - eBook - ePub

'Abd al-Rahman III

The First Cordoban Caliph

- Maribel Fierro(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Oneworld Academic(Publisher)

AL-ANDALUS BEFORE THE SECOND UMAYYAD CALIPHATE (EIGHTH–NINTH CENTURIES) WHAT WAS AL-ANDALUS? Al-Andalus was the name given by Muslims to the Iberian peninsula, and in a more restricted sense, the name given to the territory under Muslim rule. That territory was not always the same.Until the eleventh century, most of the Iberian peninsula was controlled by Muslims, except for the northern regions, where small Christian kingdoms emerged. That the core of Muslim settlement and rule lay in the south is indicated by the location chosen for the capital of al-Andalus. The Visigoths, the former Germanic rulers of the Iberian peninsula, who had entered from the north, had established their political and religious capital in Toledo, situated roughly in the middle of the peninsula. Toledo fell into Muslim hands when Muslim armies conquered the Iberian peninsula in the second decade of the eighth century and it had a crucial role in frontier politics, being often referred to as the “capital” of the Middle Frontier of al-Andalus. But it was Cordoba, a town further south, that became the seat of the Muslim governors and later of the Umayyad rulers of al-Andalus.In 1085, Toledo was occupied by Alfonso VI, king of Castille and León, and lost forever to the Muslims. By then, the Umayyad caliphate founded by ‘Abd al-Rahman III in the tenth century had collapsed, and al-Andalus was divided into the so-called Party kingdoms, a division that gave the Christians the opportunity to interfere in their internal politics and more importantly, to extract monetary payments from them. The strengthening of their military capabilities as the Christians established “societies organized for war” ran parallel to the inability of the Muslim inhabitants of al-Andalus to raise competent armies to face the Christian enemies from the north. After the fall of Toledo showed how dangerous their situation had become, the Party kings realized the urgency of looking for help. - eBook - ePub

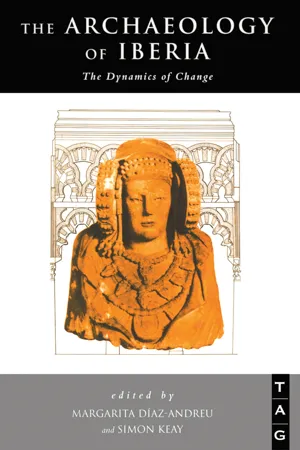

The Archaeology of Iberia

The Dynamics of Change

- Margarita Diaz-Andreu, Simon Keay, Margarita Diaz-Andreu, Simon Keay(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Chapter Fourteen The Origins of Al-Andalus (Eighth and Ninth Centuries) Continuity and change Vicente Salvatierra Cuenca IntroductionAl-Andalus is the name the Arabs gave to their domains in the Iberian Peninsula (Figure 14.1 ), a territory that gradually decreased as the Christian feudal societies progressed in their steady advance southward. Beginning in AD 711, the Arabs shattered Visigothic control of the Peninsula and in the ninth century, during the Ummayad emirate, the ‘Islamic’ border moved back to the Duero, largely because of the acute political crisis of the Ummayad emirate in the last thirty years of the century Under Abd al-Rahman III (AD 912–61), the first caliph of Al-Andalus, the central authority emerged again, settled the border on the Duero and harassed the Christian kingdoms. In the eleventh century, by which time the caliphate had been replaced by the Taifa kingdoms, the border was formed by the river Tagus, only undergoing minor variations during the twelfth century on account of the Berber (Almoravid and Almohad) counter-offensives. From the thirteenth century onwards, Al-Andalus became reduced to the Nasrid kingdom, and in the fourteenth century was finally limited to the provinces of Almería, Granada and southern Jaén, before it disappeared in the late fifteenth century (Figure 14.2 ).Figure 14.1 Map showing the withdrawal of the frontier of Al-Andalus between the mid-eighth and thirteenth centuries.Figure 14.2 Map showing the location of Jaén province in Andalucía (above) and its principal geographical features (below).The analysis of the written sources of that time, which were mostly of a political and military nature, has overlooked the study of the territory and the settlements. As a result, some scholars have thought that the invaders occupied the already existing nuclei of population. In terms of residence and economy, the population is understood to have been largely urban-based from the beginning, with few subsequent changes. In recent years, however, archaeological research in south and eastern Iberia has focused upon this issue and suggests a substantially different picture. - eBook - ePub

The Almohad Revolution

Politics and Religion in the Islamic West during the Twelfth-Thirteenth Centuries

- Maribel Fierro(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

658/1260) can be read as a chronicle of the loss of al-Andalus, as it reflects the emigration of ‘ ulamā ’ from the conquered towns. 29 With few exceptions, Muslim authors show in their writings the acceptance of the inevitability of a process for which no solution was conceived, except intervention from outside. It seemed as though the loss of al-Andalus foretold in Prophetic traditions was to become reality. Some of those prophecies had been circulating since the 2nd/ 8th century and can be found in the eschatological literature produced in the 6th/12th–7th/13th centuries, such as Ibn al-Ḫarrāṭ’s (d. 581/1185) Kitāb al-‘āqiba and al-Qurṭubā’s (d. 671/1272) al-Taḏkira fī aḥwāl al-mawtā wa-‘ulūm al-āḫira. 30 History was fulfilling the belief that al-Andalus had been doomed from the beginning. Nu‘aym b. Ḫammād (d. 228/843) had recorded in his Kitāb al-fitan a tradition describing how the inhabitants of al-Andalus would be forced to leave their land, unable to stop the Christians, and how God would then open the sea to allow them to cross the straits and take refuge in North Africa. 31 From the 7th/13th century onwards, the story was often related of how the caliph ‘Umar b. ‘Abd al-‘Azīz (d. 101 / 720) had tried to force Muslims to leave the “island” (ğazāra) of al-Andalus, because it was too far from the rest of the dār al-islām and because of its isolation, surrounded as it was by sea and by Christians (rūm). 32 2. MUSLIM PERCEPTIONS OF CHRISTIANS DURING THE 12TH–13TH CENTURIES IN AL-ANDALUS The image of Christians in chronicles and related writings during the Umayyad and Taifa periods has been dealt with in a number of studies. 33 They show how often more attention was paid to the “Arab” ethnic identity of Andalusīs, as opposed to Berber, than to their religious identity as Muslims, as opposed to Christians - eBook - ePub

What Was the Islamic Conquest of Iberia?

Understanding the New Debate

- Hussein Fancy, Alejandro García-Sanjuán, Hussein Fancy, Alejandro García-Sanjuán(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Cultural memories of the conquest of al-Andalus between the ninth and twelfth centuries, C.E. Janina M. SafranABSTRACTThis essay takes up the subject of the conquest of al-Andalus as a conceptually originative act in a discussion of group identity and memory. The focus is not on Umayyad rule and memory, except in so far as Umayyad rule structured the historical perspectives of Andalusi writers, but on Andalusi Mālikī jurists and their social memory. The way Andalusi Mālikī jurists represented their community, its origins, and their relation to the past changed and varied over the period of the rise and fall of Umayyad rule in Iberia and the establishment of Almoravid rule, as their own structures of power developed with the systematization of legal learning and practice. The essay demonstrates these developments through analysis of biographical texts written by jurists in the ninth, tenth, and twelfth centuries and suggests how the conquest of al-Andalus, real and imagined, fits into a history of Mālikī community, “textual polity,” and “empire.”If we think of the conquest of al-Andalus in 711 in terms of the Iberian Peninsula's integration into the domain of Islam, we immediately recognize the conquest to be about more than Muslim commanders and their soldiers staking a claim to land. The Umayyad achievement of a dynastic rule that endured from the middle of the eighth century to the early eleventh century provided the political framework and patronage for the development of institutions and practices that defined al-Andalus as an Islamic state. That is, the Umayyads established and maintained a polity – an amirate and then, in the tenth century, a caliphate – that conformed to and articulated conventions of Islamic governance. The Umayyads closely supported the establishment and maintenance of Islamic law in their lands through their practices of rule and patronage of scholarship, contributing to the emergence of Cordoba as a regional center in the development and promotion of the emergent Mālikī madhhab or legal tradition. Without overemphasizing their distinctiveness, I would like to suggest two (enmeshed) cultural systems unfolded in the period between the eighth and the eleventh centuries through the agency of participants in overlapping spheres: one defined by and defining Umayyad structures of political power and authority and one defined by and defining a Mālikī network of scholars with its own structures of power and authority. Both systems contributed to the “symbolic universe” of al-Andalus under Umayyad rule. Umayyad political culture informed practices and expressions of political authority and legitimacy in the region both during and after the collapse of Umayyad rule. Jurists in Iberia were bound to the history of the Peninsula but also belonged to an emerging Mālikī “textual polity” – a community defined by, and invested in, the authority of texts and scholars. Brinkley Messick’s concept of “textual polity” is useful here as a way to articulate how text-based knowledge constituted Mālikī authority in al-Andalus and how scholars developing disciplines of learning imposed Mālikī authority and generated hierarchies of expertise. Messick demonstrates through his study of Yemen in The Calligraphic State how authoritative texts involve “structures of authorship, a method of instructional transmission, institutions of interpretation, and modes of documentary inscription” and how textual authority “figures in state legitimacy, the communication of cultural capital, relations of social hierarchy, and the control of productive resources.”1 - María Marcos Cobaleda(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

2016 ).Passage contains an image

© The Author(s) 2021Begin AbstractM. Marcos Cobaleda (ed.)Artistic and Cultural Dialogues in the Late Medieval Mediterranean Mediterranean Perspectives https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-53366-3_66. Granada and Castile in the Shared Context of the Islamic Art in the Late Medieval Mediterranean

End AbstractJuan Carlos Ruiz Souza1(1) Departamento de Historia del Arte, Complutense University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain6.1 Introduction1 : Why Should We Have to Expand the Context to Understand the Andalusi Art?

Nasrid Granada, the last remaining kingdom of al-Andalus, and Castile , in the late Middle Ages, had common goals within the arts (political and religious messages); they must be studied in context of Islamic art. Before going any further it is important to consider Andalusi art as both a creative centre and a mere periphery between Islamic art and Spanish art. We need to understand how historiography has established differing views about the role of Andalusi art in the construction of the Spanish medieval art depending on the researchers’ goals. We shall continually state in this chapter that there was a very rich shared cultural context.The importance of palaces as monuments in the city-palace of the Alhambra and the Generalife is such that they have monopolised and isolated Nasrid art from the general context of Islamic culture because, today, the territories of al-Andalus belong to a country of Christian culture. On the other hand, when the arts in Castile have to do with those of al-Andalus , they are often been studied in a differente chapter (Mudéjar art ) because they were promoted for a medieval Christian society. Many buildings of the Crown of Castile, such as the Royal Alcazar in Seville , among other palaces , are linked to Islamic art in addition to Islamic funerary constructions: spaces with a dome and a centralised plan (qubba), sometimes covered by muqarnaṣ domes (Ruiz Souza 2001a , p. 9–36), etc. In this article, we shall mention buildings from Castile, al-Andalus , Egypt , Sicily , Syria , Morocco- Maribel Fierro(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

The ‘second Taifas’ that sprang up in the Algarve, Almería, the Balearic Islands, Badajoz, Cadiz, Cordoba, Granada, Guadix, Jaén, Malaga, Murcia, Seville and Valencia never had time to achieve the importance that their precursors had. Within a few years, beginning in the Algarve in 537/1142, the new Taifas fell one by one to Almohad forces, with Murcia the last to be occupied, in 567/1172, and the Balearic Islands much later in 599/1203. By the middle of the sixth/twelfth century, the bulk of al-Andalus had passed within the orbit of a new empire. In its decline, with its initially strict religious orthodoxy weakening, the Almoravid empire began to lose territory to Christian armies. One of the reasons for its decline is related to the relatively demilitarised character of Andalusı ¯ society, which had to resort to assistance from the more bellicose Maghrib, while by contrast the Christian societies of the northern Peninsula were ‘organised for war’. Nevertheless, the approximately fifty years of Almoravid domination in al-Andalus demonstrated that even territorial uni- fication imposed from outside could not stem the steady loss of Andalusi territory. Meanwhile, North Africa was overrun by the Almohads, who had mounted the most effective and long-lasting of the several uprisings against the Almoravids in North Africa. The New Cambridge History of Islam 44 Notes 1. Discussion of the sources for this period is found in L. Molina, ‘Historiografía’, in M. J. Viguera Molins (ed.), Historia de España Menéndez Pidal, vol. VIII-1, Madrid, 1994, 3–27; M. J. Viguera Molins, ‘Historiografía’, in Viguera (ed.), Historia de España Menéndez Pidal, vol. VIII-2, Madrid, 1997, 3–37; D. J. Wasserstein, The rise and fall of the party-kings: Politics and society in Islamic Spain, 1002–1086, Princeton, 1985. 2. Analysed in C. Mazzoli-Guintard, Vivre à Cordoue au moyen âge: Solidarités citadines en terre d’Islam aux Xe–XIe siècles, Rennes, 2003.- eBook - ePub

- Maribel Fierro(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

We have already mentioned the tradition of Mudejar art as one example of a long history of an aesthetic taste articulated around Arab elements. Thus, it is not surprising that these impressive works of Andalusi architecture were, in general, not considered symbols of an enemy religion that should be demolished, but rather as architectural wonders to be appropriated. The classic example of this is the construction of the Palace of Charles V inside the Alhambra complex, one of the most extraordinary works of Spanish Renaissance architecture. This combination of Renaissance manners of construction with Arab elements, especially decorative motifs, gave rise to such remarkable buildings as Seville’s “Casa de Pilatos”. The person responsible for the palace’s current form is Fadrique Enríquez, Marquis of Tarifa, who, following a pilgrimage to the Holy Land (1518–1520), wanted to reproduce the Stations of the Cross to scale in Seville, the first station being the Casa de Pilatos itself. 18 Here, as in the foregoing examples, this aesthetic programme fusing Renaissance forms with Mudejar decoration was at the service of the sacralization of the urban landscape; it was thus the formal vocabulary of al-Andalus, stripped of its Muslim character, which served to express this reference to the ancient Orient. As with other linguistic, material and cultural resources of Iberia’s past, these traces of al-Andalus ended up forming part of the process of writing Spain’s national history, which was particularly active in the sixteenth century. In contemporary Spanish history books, al-Andalus often comes up as part of the history of the long medieval military expansion of the peninsular Christian kingdoms, a narration articulated around the themes of the “loss” and “recovery” of Spain. However, this narration is one full of nuances - eBook - ePub

Christians, Muslims, and Jews in Medieval and Early Modern Spain

Interaction and Cultural Change

- Mark D. Meyerson, Edward D. English, Mark D. Meyerson, Edward D. English(Authors)

- 2000(Publication Date)

- University of Notre Dame Press(Publisher)

2 Foremost among his Andalusian masters in jurisprudence (along with his father) were the esteemed Rabbi Isaac Alfasi and his great Lucenan heir Rabbi Joseph ibn Megas, whom Maimonides reverently called “my teacher.” For Maimonides, Andalusian scholars had virtually eclipsed the Babylonian geonim. Jewish scholarship had been transported from the East to Andalusia, and Córdoba rivaled Baghdad in intellectual splendor, much as learning in the Islamic world had been transferred from East to West in the tenth century. By the twelfth century, Andalusian culture in Arabic and Hebrew was well racinated, and Abū al-Walīd ibn Rushd and Mūsā ibn Maymūn were confident, but their Andalusian insistence may still have been tinged by what the literary scholar Harold Bloom called an “anxiety of influence,” expressing itself as a quest for independence and superiority over influential past authorities.Maimonides extols the philosophical heritage of Andalusian Jews because they quite properly kept philosophy and theology asunder. Discussing philosophy and Kalām, he observes (expressing an odium theologicum for the latter):3 “As for the Andalusians among the people of our nation,4 all of them cling to the affirmations of the philosophers and incline to their opinions, in so far as these do not ruin the foundation of the Law. You will not find them in any way taking the paths of the Mutakallimūn.” The statement is hardly true; for Andalusian Jews, like Joseph ibn Saddiq and Baḥya ibn Paqūda, wandered down some Kalamic paths.5 Maimonides’ hyperbole merely accents his cultural bias and intellectual parti pris.In medicine, Maimonides displays a Western orientation. He studied medicine in the Maghrib before coming to Egypt, had high regard for Maghrebi physicians, and refers in his medical works to practices he witnessed there.6 His Sharḥ Kitāb al-ʿUqqar is a product of an Andalusian—but also Egyptian and common Mediterranean—environment. He gives the names of pharmaceuticals in Arabic, Greek, Spanish (even colloquial), Berber, and vernacular Egyptian, whilst omitting Hebrew.7Maimonides’ knowledge of mathematics and astronomy also locates him in an Andalusian ambience. Among works on mathematics which Muslim authors ascribe to Maimonides,8 al-Qiftī mentions Maimonides’ revision of al-Muʾtamin ibn Hūd’s Istikmāl. The author, a scholar and scientist (d. 1085), was of the Hudid dynasty of Saragossa, of the mulūk al-ṭawāˀif (reyes de Taïfas) in eleventh-century Spain. A member of the Ibn Hūd family taught the Guide to a circle of Jews in Damascus.9 Maimonides studied astronomy in Spain and was in touch with a student of Ibn Bājja and with a son of the astronomer Jābir ibn Aflaḥ, and edited an astronomical treatise of Jābir.10 - eBook - ePub

Charting Memory

Recalling Medieval Spain

- Stacy N. Beckwith(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Shmuel Refael contextualizes gendered processes of name-giving among Salonikan Sephardim within a wider field of Judeo-Spanish onomastics. He also maps pre-Holocaust Salonika through the humor that prompted the names and nicknames of its many synagogues and Ladino newspapers. These refer not only to precise locations in Spain, but to everyday medieval/contemporary realia and character traits, as well. Hsain Ilahiane similarly reconnects residential balconies in the Jewish quarters of Moroccan cities to Sephardic Andalusian models and sources, reading the history of the Islamic City “against the grain,” and stressing the persistence of such architectural features as an expression of Iberian cultural memory.The collection takes a wider turn in its final section, beginning with Sultana Wahnón’s analysis of the built and soft features of Latin American non/remembrance of the Sephardic conversos and their travails in New Spain, as Gabriel García Márquez’s broaches in One Hundred Years of Solitude. Dwight Reynolds then charts the history and continued growth and diversification of popular Arab Andalusian music from Manama, Bahrain, to Los Angeles. Emotional ties to a shared Iberian past are also the keynotes that sound in Reuven Snir’s study of al-Andalus, as recalled in both the content and stylistics of Arab poetry from the medieval period through the 1990s. Federico García Lorca is particularly invested with medieval/modern connectivity, and revered by contemporary poets who have broad cultural, as well as specific national appeal.Sephardim in Indianapolis today do not have such an icon and direct link to Spain, and indeed the waning of social mnemonic frameworks among older Balkan Sephardic immigrants in the United States may ensure little more than the persistence of general recollections of an Iberian “golden age.” Nonetheless, Jack Glazier’s study underscores that it is in communities constructed by families, synagogues, language, and folklore, that collective memories of recent and remote Sephardic pasts have crystallized. As a whole, this volume examines a range of textual and nontextual praxes related to various Jewish, Arab, and Hispanic memories of medieval Spain. It localizes these memories in social frameworks that have formed and re/grouped interdiscursively, such that they do recall convivencia - eBook - ePub

On Earth or in Poems

The Many Lives of al-Andalus

- Eric Calderwood(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Harvard University Press(Publisher)

ʿ Abd al-Rahman III).The voice-over also marks a new theme in ʿ Ali and Sayf’s trilogy: the idea that Umayyad al-Andalus was a site of cross-cultural exchange—“a mighty example of the blending of civilizations.” This idea is a variant of the long-standing motif of convivencia, and it responds to the post–9/11 context in which the trilogy was made. Hatim ʿ Ali spoke directly to this issue in an interview with anthropologist Christa Salamandra in 2007. In the interview, the Syrian director described the circumstances that led him to make a trilogy about al-Andalus:I think we are on the brink of a true war of civilizations, one that is not limited to a battle of ideas, but is about to develop into a confrontation using traditional and probably not traditional weapons, in the future. In light of this, I began a project about the rise of the Andalusian state, which is probably a unique, exceptional experiment in the history of human kind, where you found, in one place on earth, Muslims of all ideologies, ideas, and aspirations, along with Christians—the original inhabitants of the land, and Jews. The presence of all of these in one place, in a democratic atmosphere, in a dialogue of civilizations, allowed for the establishment of one of the most important human civilizations, the Andalusian civilization, which was, I think, the gate through which Greek civilization entered what is today called Europe.101In these revealing comments about the genesis of his Andalus trilogy, ʿ Ali draws on a few key terms that dominated geopolitical debates at the turn of the millennium. First, ʿ Ali positions his trilogy as a response to a mounting “war of civilizations”—a phrase that seems to be an allusion to Samuel Huntington’s much-debated notion of the “clash of civilizations.” Huntington’s thesis, formulated in the early 1990s, was that the primary source of conflict in the post–Cold War world would be competing cultural and religious identities.102 Huntington warned, in particular, of an inevitable clash between “Western civilization” (his phrase) and the Muslim world. Huntington’s thesis sparked a broad range of responses in the fields of international diplomacy and political science. Among them was the UN’s decision, in 1998, to designate the year 2001 as the “United Nations Year of Dialogue among Civilizations.”103 The UN initiative, which stretched beyond 2001, was presented as an alternative (and even a rebuke) to Huntington’s ideas. For instance, a UN press release about the initiative quoted a member of the UN General Assembly saying: “Instead of accepting that international dynamics would lead civilizations to clash, the international community should strive to create a bounteous crossroad of civilization.”104 - Brian A. Catlos(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Revolt in Andalucía No sooner had the uprising in Valencia been quelled than another flared up in Castilian-controlled territory, both in the Guadalquivir valley, which had been conquered, and in Murcia, which was ruled by Alfonso X’s vassals, the Banu ¯ Hu ¯ d, and their rivals, the Banu ¯ Ashqı ¯lu ¯ la. While the cities and major towns of the Guadalquivir had been all but purged of their free Muslim inhabitants (although there were undoubtedly significant numbers of slaves), a substantial Muslim population remained in the country, cultivating the land and practicing crafts as they had previously, but now living as tributaries of the Christian sovereign. They enjoyed broad communal autonomy and privileges, and some were granted the right to maintain fortified refuges for their own protection. Organization was local in nature, and the power of local warriors (alcaldes, from the Arabic, al-qa ¯ pid, al-quwwa ¯d) and the authority of councils of elders 72 R. Burns and P. Chevedden, Negotiating Cultures, pp. 107 and 117. 73 Jaume I, The Book of Deeds, p. 279 {373}. A triumph of pragmatism 71 (sheikhs, or shuyu ¯kh) was officially recognized. 74 Decades of warfare had left the infrastructure of these areas devastated, however, contributing to a shift away from irrigated agriculture towards herding, and the weakening of the native socio-cultural fabric. The conquest itself was concluded in 1262, when Alfonso had reduced by force the last remaining focus of Andalusı ¯ resistance, the “kingdom of Niebla” (Labla), whose major cen- ter was Huelva (Walba). 75 In the meanwhile, Castilian determination to colonize and absorb the region of Murcia led to infringements of the terms of the Pact of Alcaraz, feeding popular and elite discontent. 76 As a con- sequence, the Banu ¯ Hu ¯ d joined with the Marı ¯nids and Granada in plan- ning a region-wide uprising, including a plot to kill the King in Seville.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.