History

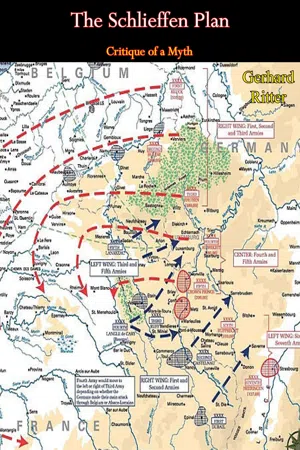

Schlieffen Plan

The Schlieffen Plan was a military strategy developed by German Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen in the early 20th century. It aimed to quickly defeat France by swiftly invading through Belgium and then turning east to confront Russia. The plan ultimately failed due to logistical and strategic challenges, leading to a prolonged and costly war on the Western Front during World War I.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Schlieffen Plan"

- eBook - ePub

- Paul Kennedy(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

9 The Significance of the Schlieffen Plan L. C. F. TurnerINTRODUCTIONFew historians would question the immense importance of the Schlieffen Plan which set the pattern for the opening battles and for much of the course of the First World War. Moreover, the plan strongly influenced the decisions taken by political and military leaders in July 1914, and must be regarded as a major factor in the chain of events which plunged Europe into war. Although historians have been referring to the plan for more than forty years, its text was not published until 1956, when Gerhard Ritter produced his outstanding study of the plan and its consequences.1 The German official histories published between 1920 and 1939 gave only fragmentary information about the plan and, as a result, all discussions of the subject before 1956 reveal serious misconceptions. Ritter’s conclusions, and those of Liddell Hart in the preface to the English edition of his book, are open to question on important points, while the publication of new material between 1956 and 1965 calls for a reassessment of some of Ritter’s contentions. The purpose of this chapter is to examine the political and military implications of the Schlieffen Plan in the light of Ritter’s writings and those of other authorities.DEVELOPMENT OF THE PLAN , 1891–1906When Count von Schlieffen became Chief of the German General Staff in 1891, he took over the plans for a two-front war, which had been designed by the elder Moltke and which had been adhered to basically by his successor, Waldersee. As is well known, Moltke was far from being dazzled by his victories in 1870; he did not believe that his rapid triumph over France could be repeated and his operational plans for a future war were marked by extreme caution. In 1879 Moltke outlined his strategy against France and Russia.2 - eBook - ePub

- Geoffrey Wawro(Author)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

History of the Art of War and was struck by Delbrück’s account of the battle of Cannae in 216 BC. Cannae was the greatest feat of ancient arms; with just 25,000 men, Hannibal had annihilated an army of 50,000 Roman legionaries. Hannibal had accomplished this by wheeling his Carthaginians around the flanks of the Roman legions to hit them in the rear, where they were thinly defended and easily panicked. The Carthaginians killed 48,000 legionaries in the course of the battle, effectively disarming the Romans. Since Schlieffen too was outnumbered on the order of two-to-one, he took Cannae as a kind of model for a war with France and Russia. Hannibal had succeeded because he had skirted the Roman front and struck instead ‘along the entire depth and extension of the hostile formation’, pushing chaos and panic into the Roman legions from the flank before rolling them up from behind (Bucholz 1991: 156–7). Schlieffen proposed to apply the same basic principle to a war with the French. A German army invading France would not tiptoe up to the excellent French fortifications around Verdun and Belfort and obligingly deploy itself for a siege, rather it would hook through Belgium and Luxembourg, brush past the foremost French armies and fortifications, turn into their rear and pulverize them from behind. Liddell Hart aptly characterized Schlieffen’s plan as ‘a revolving door’ (Liddell Hart 1964: 68–9). The German army would revolve through neutral Belgium and Luxembourg to bypass France’s eastern forts, pivot west of Paris, and then circle in behind the French army, crushing it against the Jura and the Swiss border.Although some questioned the violation of Belgian neutrality on the grounds that it would draw England into the war, Schlieffen retorted that ‘a German army that seeks to wheel around Verdun must not shrink from violating the neutrality of Belgium as well as that of Luxembourg’ (Stone, in Kennedy 1979: 224). If the British dispatched an expeditionary force to defend Belgium or disengage the French, so much the better. The British army would either be knocked into the sea or scooped up and driven with the French and the Belgians towards France’s eastern border to be destroyed by the massed German army at their rear, and a smaller German force that would seal Schlieffen’s ‘pocket’ in Alsace-Lorraine (Herwig 1997: 46–7; Turner, in Kennedy 1979: 204–5). The most striking feature of the Schlieffen Plan was its confident disregard of political complications (like the attitude of England, Belgium or Holland), and the ease with which Germany’s civilian decision-makers were persuaded to accept it. The Kaiser backed the plan from the start, as did his chief ministers. In 1900 Schlieffen discussed his plan with government officials for the first time. Friedrich von Holstein, the German foreign ministry’s elder statesman, spoke for his colleagues when he said: ‘If the Chief of the Great General Staff, and particularly a strategic authority such as Schlieffen, thought such a measure to be necessary, then it would be the duty of diplomacy to adjust itself and prepare for it in every possible way’ (Bucholz 1991: 177; Turner, in Kennedy 1979: 206–7; Joll 1992: 100–1).In the years after 1900, Schlieffen carefully plotted the Cannae-like encirclement of the French. At first, he planned merely to deploy the bulk of the German army against the French. Then, in 1904–5, something extraordinary happened; Russia, France’s key ally, was flattened by the Manchurian War. With its navy destroyed, its army gutted and its peoples convulsed by the Revolution of 1905, Russia was rendered all but useless to the French for several years. This permitted Schlieffen to take his slowly maturing plan to its logical conclusion: in 1905, he stripped Germany’s eastern defences to mass the entire German army–nearly two million men–against a French army that would have been hard-pressed to muster 800,000 combat troops. A recent study of European war plans and armaments indicates that had the First Moroccan Crisis in 1905 ended in war, the Germans would probably have won it. Untroubled by the Russians, they would have enjoyed unbeatable odds against France (Herrmann 1996: 45–51). - eBook - ePub

The Schlieffen Plan

International Perspectives on the German Strategy for World War I

- Hans Ehlert, Michael Epkenhans, Gerhard P. Gross, David T. Zabecki, Hans Ehlert, Michael Epkenhans, Gerhard P. Gross, David T. Zabecki(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- The University Press of Kentucky(Publisher)

The Schlieffen Plan—A War Plan Robert T. FoleyIn an article published in War in History in 1999, Major Terence Zuber set out to challenge one of the longest-held interpretations about origins of the First World War.1 Zuber set himself the task of reexamining German war planning during the tenures of Alfred Graf von Schlieffen and Helmuth von Moltke the Younger. Using previously unknown documents, he painted a much more detailed picture of this war planning than had hitherto been available. He showed the minutiae of Schlieffen’s deployment plans from 1892 to 1904 and demonstrated how German commentators in the interwar period and later historians, most notably Gerhard Ritter, had simplified and even altered the details of these plans in their writings.However, Zuber went much farther in his analysis than merely adding much-needed detail to our understanding of German war plans before the First World War. He challenged the traditional interpretation of Schlieffen’s memorandum of 1905, the infamous Schlieffen Plan.2 Indeed, Zuber went so far as to argue that there had never been a Schlieffen Plan. Instead, he contended that Schlieffen’s memorandum of 1905 was not a blueprint for a future German deployment, but rather was an elaborate attempt to get more troops out of a reluctant Ministry of War.3 Going farther, Zuber argued that far from planning to fight an offensive war, Schlieffen had always intended to remain on the strategic defensive and await his enemies’ attacks. In Zuber’s analysis, neither Schlieffen nor his successor, Moltke the Younger, ever intended to launch an invasion of France with a powerful right wing enveloping the French fortress line. In short, in a challenge to the long-accepted interpretation, Zuber argued that Schlieffen, and later his successor Moltke, never intended Germany to be the aggressor in a future war.4One aspect of Zuber’s far-reaching analysis has been critiqued by Terence Holmes. Holmes has subjected Schlieffen’s 1905 memorandum to a close textual analysis, and has shown this document to be much more complex than previously understood. He has demonstrated that this memorandum was not the disastrous operations plan with a simplistic drive on Paris assumed by Zuber, but rather a sophisticated document that provided for a variety of scenarios.5 While Holmes’s perceptive analysis of Schlieffen’s memorandum is perhaps one of the most important points to come out of the debate, it does not deal directly with some of Zuber’s wider claims, and that is the aim of this chapter. It will leave aside the operational detail of the Zuber-Holmes debate and concentrate on an examination of Zuber’s wider argument.6 - Walter Görlitz, Walter Millis, Brian Battershaw(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Lucknow Books(Publisher)

In so far as these considerations proved decisive for Schlieffen, the French calculations may be said to have been justified, but with the Ardennes ruled out, there remained only Belgium. Prussia, like all other leading European powers, had guaranteed Belgian neutrality when Belgium achieved her independence. An orderly political leadership, such as existed under Bismarck, would probably have refused to go back on that pledge—assuming that such a leadership would ever have allowed the political situation to deteriorate to a point where so dangerous a venture could have had attraction—but Schlieffen’s relations with Hohenlohe, the Chancellor, and with Bülow, his successor, were quite superficial. Neither of these men, in the eyes of the General Staff, commanded Bismarck’s prestige, and so within their own province the military planned entirely on their own. When he heard of the plan to violate Belgian neutrality, Holstein, the secret manager of the Foreign Office (from whom Schlieffen derived such knowledge of international affairs as he possessed), preferred to let sleeping dogs lie, and no doubt vaguely hoped that the occasion for applying it would not arise. Schlieffen knew enough history to realize that a violation of Belgian soil carried the danger of British intervention. He set no great store by the possibility of an English landing in Denmark, or of an attack on the Kiel canal, believing, as he did, that he could defend himself in that quarter with negligible forces. If, on the other hand, British forces appeared in Belgium or Northern France, they would simply be drawn into the general catastrophe of the French Army and reduced to impotence.III —Belgium fortifies Liège and Namur—Birth of the Schlieffen Plan

Every year the plans were worked over afresh, but it was only slowly that, under the influence of events as a whole, the great master plan began gradually to take shape. Through the greater part of the ‘nineties, the bogey of encirclement gave it actuality; then, in 1898, 1899 and 1901, England sent out feelers to see if an understanding could not be arranged between the greatest sea power and the greatest land power. But the opportunity was thrown away; neither Bülow nor Holstein approved of firm commitments for Germany, who would thus lose her bargaining power and so fall between two stools.Finally, England gave up her search for an Anglo-German rapprochement.- eBook - ePub

The Ideology of the Offensive

Military Decision Making and the Disasters of 1914

- Jack L. Snyder(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Cornell University Press(Publisher)

Perhaps the most common criticism of the Schlieffen Plan is that it made the fear of a two-front, general war in Europe a self-fulfilling prophecy. Because of the time pressures in the plan, any Russian mobilization would require an immediate German attack on France. Thus there could be no chance to localize a Balkan conflict—no chance for either side to posture militarily, negotiate, and demobilize. The Schlieffen Plan prepared for the worst case in a way that ensured that the worst case would occur.The Schlieffen Plan similarly helped to bring about the British blockade that it was in part designed to avoid. The fear of blockade helped the Germans to rationalize the need for the quick victory that could only be obtained by violating Belgian neutrality. But that violation helped to bring Britain into the war, and the feared blockade became a reality. Had Germany respected Belgian neutrality and generally remained on the defensive in the west, British neutrality would have been reasonably likely. Indeed, as late as 1 August 1914 Foreign Minister Edward Grey was suggesting that Britain could remain neutral on precisely those terms.28 Two recent historians of Anglo-German relations argue that Britain’s only substantial motive for war was to prevent German hegemony on the continent. They speculate that hegemony would not have been at issue had Germany fought the war defensively, and Britain would probably have stayed neutral.29Schlieffen and especially Moltke were quite sensitive to the Schlieffen Plan’s shortcomings. In a 1913 memorandum, probably in response to a request from Foreign Secretary Gottlieb von Jagow to reconsider the planned invasion of neutral Belgium, Moltke expressed serious doubts about the political advisability and operational feasibility of the Schlieffen Plan.30 But all the alternatives at the time seemed worse.Alternatives to the Schlieffen Plan

Yet despite the conclusions of the General Staff, strategically sound alternatives to the Schlieffen Plan were available. Drawing on the war plans of the elder Helmuth von Moltke in the 1880s and the 1915 campaign on the eastern front, several German observers have argued that the best strategy available to Germany in 1914 was to defend in the west and to wage a limited offensive in the east. While such a strategy would have had a better chance than the Schlieffen Plan of achieving Germany’s political and security aims, it could not have promised rapid, low-cost, and decisive victory. Since Schlieffen and the General Staff placed an absolute value on these latter criteria, schemes for a more likely, but also more costly and more limited victory were not even considered. - eBook - ePub

The Schlieffen Plan

Critique of a Myth

- Gerhard Ritter, Eva Wilson, Andrew Wilson, Eva Wilson, Andrew Wilson(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Eschenburg Press(Publisher)

For the risk was great indeed—hi fact, it was immense. Nobody who studies the complete text of the Schlieffen Plan carefully can fail to gain this impression—particularly when comparing the final version with the preceding drafts. The former represses or suppresses many doubts and objections which come out clearly in the latter. They are all the more serious because the plan of December 1905 only reckoned with a war on one front—a different situation from that in 1914—and only with an enemy who was firmly resolved—again in contrast to 1914—to stay cautiously on the defensive. Here we touch on the first of the doubts which the great Schlieffen Plan raises: did its author assess the defensive and offensive power of the enemy correctly? So little did he fear a French counterattack that he would have welcomed it as a “good turn,” as the best chalice to beat the French decisively in the open field. He was utterly convinced of the superiority of the German Army in open battle. His only worry seems to have been that the enemy would hide behind his chain of fortresses or behind a succession of river valleys, or even withdraw to the south of France and so prolong the war indefinitely. The envelopment was an attempt to avoid both these contingencies.It is certain that Schlieffen’s idea of the French operational plan corresponded closely with the defence plans of the French General Staff (plan 15 bis ).{79} It is equally certain that this no longer held good for the enemy hi 1914 who, as we know, launched two offensives at the very start of the war. One was a feeble advance into Alsace-Lorraine, planned merely as a diversion; the other a large-scale attempt to break through the centre of the German front in southern Belgium, in the direction Dinant-Namur. The encounters which followed gave proof of the Germans’ superiority in attack, which Schlieffen had foreseen. But at the same time his hope that these encounters would lead to the enemy’s “annihilation” received its first disappointment, not through any lack of offensive spirit on the part of the Germans, but through the army commanders’ inadequate orientation and those “frictions” inevitable in war. The attacker was not “annihilated” but only driven back in an “ordinary frontal victory,” to use Schlieffen’s expression. In the course of this action and all subsequent ones, it became clear that the central leadership of a million-strong army, for which the German General Staff lacked all practical experience and therefore technical preparation, was much more difficult than Schlieffen had imagined. His idea was that “all army commanders should fully acquaint themselves with the plan of the supreme commander, and one thought alone should permeate the whole army.” General Staff officers at the higher levels were to be mere “chessmen” of the Supreme Command, and the advance through Belgium was to be carried out “like battalion drill.”{80} Later on, the younger Moltke was often accused of allowing his army commanders too much independence (in which he followed the example of his great uncle); and it may well be that a strategic plan like Schlieffen’s of 1905 could only have been carried through by means of tight control from the centre. But was it only the shortcomings of the Supreme Army Command in 1914 which caused this central control to fail? When Moltke took over, he already had doubts as to whether a central control of battle and manœuvre in Schlieffen’s sense would be practicable in the event of war. And Schlieffen’s method of directing manœuvres was under fairly widespread criticism before 1914.{81} - eBook - ePub

Power Shifts, Strategy and War

Declining States and International Conflict

- Dong Sun Lee(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

4 The Schlieffen Plan and World War IThe historic case of World War I has been the main battleground for rival theories of power shifts and war. Scholars claim that their preferred theory can offer a compelling – if not superior – explanation for the war’s origins. In this chapter, I join the high-stakes battle and see how well my theory fares in accounting for the monumental event. For this purpose, I trace how the German maneuver strategy called “the Schlieffen Plan” shaped the declining German state’s preventive motive and the opportunities for diplomacy and war vis-à-vis Russia in particular. I also examine how these intervening phenomena in turn led to war in the summer of 1914. This analysis pairs up nicely with that of the earlier peaceful shifts in power presented in the previous chapter: two rivals – Germany and Russia – experienced two major power shifts consecutively in four decades but avoided a war in one occasion and fought a war in the other. These contrasting outcomes constitute an interesting puzzle. This chapter also re-evaluates empirical supports for alternative accounts that the competing theories offer to the case of World War I.My theory predicts that a maneuver strategy like the Schlieffen Plan produces the following effects and thereby increases the risk of preventive war:• Preventive motive . The declining state has a strong motive for preventive actions. As a result of power shifts, the rising state can deploy larger and more efficient forces. The decliner thus may be forced to divert a portion of mobile forces and reinforce its defenses opposite the enemy’s growing main body, fearing that the entire defense may collapse prematurely. Therefore, mobile forces will become too weak to deliver a decisive blow beyond a certain point. Consequently, the declining state will come to fear that the maneuver strategy will be obsolete in the near future and will become prisoner of a “use it or lose it” mentality.• Opportunity for diplomacy - eBook - ePub

- Captain B. H. Liddell Hart(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Tannenberg Publishing(Publisher)

Britain’s contingent share in the French plan was settled less by calculation than by the ‘Europeanization’ of her military organization and thought during the previous decade. This continental influence drew her insensibly into a tacit acceptance of the role of an appendix to the French left wing, and away from her historic exploitation of the mobility given by sea-power. At the council of war on the outbreak, Sir John French, who was to command the British Expeditionary Force, expressed a doubt of ‘the prearranged plan’; as an alternative, he suggested that the force should be sent to Antwerp where it would have stiffened the Belgians’ resistance and, by its mere situation, have threatened the rear flank of the German armies as they advanced through Belgium into France. But Major-General Henry Wilson, when Director of Military Operations, had virtually pledged the General Staff to act in direct conjunction with the French. The informal staff negotiations between 1905 and 1914 had paved the way for a reversal of England’s centuries old war policy.This fait accompli overbore not only French’s strategical idea but Haig’s desire to wait until the situation was clearer and the army could be enlarged, and also Kitchener’s more limited objection to assembling the expeditionary force so close to the frontier.The final French plan was the one thing needed to make the original German plan framed by Graf von Schlieffen in 1905 a true indirect approach. Faced by the blank wall which the French fortified frontier presented, the logical military course was to go round it through Belgium. Schlieffen decided on this course, and to move as widely as possible. Strangely, even when the invasion of Belgium began, the French command assumed that the Germans would confine their advance to a narrower front, east of the Meuse.Schlieffen’s plan concentrated the bulk of the German forces on the right wing for this gigantic wheel. The right wing was to sweep through Belgium and northern France, and then, continuing to traverse a vast arc, would wheel gradually to the left or east. With its extreme right passing south of Paris, and crossing the Seine near Rouen, it would thus press the French back towards the Moselle, where they would be hammered in rear on the anvil formed by the Lorraine fortresses and the Swiss frontier.The real subtlety and indirectness of the plan lay, not in this geographical detour, but in the distribution of force and in the idea which guided it. An initial surprise was sought by incorporating reserve corps with active corps at the outset in the offensive mass. Of the 72 divisions which would thus be available, 53 were allotted to the swinging mass, 10 were to form a pivot facing Verdun, and a mere 9 were to form the left wing along the French frontier. This reduction of the left wing to the slenderest possible size was shrewdly calculated to increase the effect of the swinging mass by its very weakness. For if the French should attack in Lorraine and press the left wing back towards the Rhine, it would be difficult for them to parry the German attack through Belgium, and the further they went the more difficult it would be. As with a revolving door, if the French pressed heavily on one side, the other side would swing round and strike them in the back and the more heavily they pressed the severer would be the blow. - eBook - PDF

The First World War

Germany and Austria-Hungary 1914-1918

- Holger H. Herwig(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Academic(Publisher)

In August 1914 time was of the essence. The Schlieffen Plan was predicated on Germany being the first to mobilize, to cross enemy borders and to drive on Paris and annihilate the Anglo-Belgian-French armies within 40 days of mobilization. Nor were the Germans alone in their anxiety over speed: General Joseph Joffre, Moltke’s French counterpart, stated on 31 July 1914 that every delay of 24 hours in mobilizing the reserves would force France to yield 12–15 miles of border lands. 61 Time meant space and blood in modern war planning. The complexity of German mobilization largely accounts for Moltke’s mental crisis of 1 August. Wilhelm II, momentarily convinced that the British THE PLANS OF WAR 59 would apply the brakes to the French and that the war could thus be limited to Russia, demanded that Moltke recast the Schlieffen Plan – now in stage four – and ‘simply deploy the whole army in the east’! Aghast at the Kaiser’s ignorance of German mobilization plans and deeply shaken, Moltke with ‘trembling lips’ interjected: ‘The deployment of a host of millions of men cannot be improvised.’ To which Wilhelm II acidly replied: ‘Your uncle [the Elder Moltke] would have given me a different answer.’ 62 Therewith, in Moltke’s mind, the Emperor had broken his pledge of 8 years’ standing not to interfere in General Staff matters. Irate, Moltke wondered aloud whether Russia might also rein in short of war, thereby erasing all prospects of war! War Minister von Falkenhayn found Moltke to be ‘totally broken’ in spirit because the Kaiser apparently still ‘hoped for peace’. 63 Later that 1 August, Moltke spilled ‘tears of despair’ over the Kaiser’s orders to halt the German 16th Division at the Luxembourg frontier, an expression of ‘disappointment’ and ‘hurt’ from which he never recovered. 64 Nor did Schlieffen’s 1908 vision of the ‘modern Napoleon’ eventuate. - eBook - PDF

Wilhelm II

Into the Abyss of War and Exile, 1900–1941

- John C. G. Röhl, Sheila de Bellaigue, Roy Bridge(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

32 The only concession to which the monarch agreed was to promise to take a less active part in conducting manoeuvres in future. But he was not to keep even that promise. operational plans for a war in western europe 301 However disastrous the Frederician decision-making system was to prove under Wilhelm II, and however inclined one is to believe that regular collective consultations between the responsible authorities – the Reich Chancellor, the Foreign Office, the General Staff, the War Ministry, the Admiralty Staff and the Reich Navy Office – would have led to a more realistic assessment of the situation, it is impossible to overlook the alarming degree of megalomaniac self- delusion to which even these highly placed advisers to the Crown were subject. In the light of modern research it can scarcely be disputed that the notorious Schlieffen Plan, which was formulated at this time and envisaged a lightning attack on France via Holland, Belgium and Luxembourg, could never have achieved its aims. The same is true of the Tirpitz Plan, which had already – at the latest with the signature of the Entente Cordiale and the fears of an Anglo- German war in November to December 1904 – proved itself to be a highly dangerous mistake. But the grandiose dreams of power of the leaders of the army and navy went much further. - Hugues Wenkin, Christian Dujardin(Authors)

- 2024(Publication Date)

- Pen and Sword Military(Publisher)

At best, he felt, the end result of Hitler’s plan would be the creation of a huge salient in the style of those obtained during the First World War, swallowing up a good portion of the available reserves. He therefore advocated a more moderate solution, aiming to strike in the Liège area in order to achieve a tactical victory that would weaken the Allies through the heavy losses caused. He was joined on this point of view by Model, who in particular envisaged an attack in the Aachen sector, which he considered to be highly threatened. The idea that germinated in the heads of the generals was to provide another project that would please the Führer and be easier to implement. The German Plan 13 Two plans were finally presented at a conference held on 27 October in Fichtenhain. On this occasion, the commanders chosen to lead the two Panzer-Armeen were invited. They were General der Panzertruppen Hasso Eccard von Manteuffel and SS-Oberstgruppenführer Josef ‘Sepp’ Dietrich. General der Panzertruppen Erich Brandenberger joined them as commander of the 7. Armee. The instruction he received began: ‘The objective of the operation is to achieve a change in the entire campaign in the west and, perhaps, in the entire war by annihilating the enemy forces north of the Antwerp- Brussels-Luxembourg line.’ Hitler went on to say, ‘I have the firm resolution to insist, at all times, on the execution of the operation, even if the enemy’s attack on both sides of Metz and the forthcoming assault on the Ruhr district should result in great losses of ground and positions.’ 9 The precision of the definition of the German device under Model’s orders is refined.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.

![Book cover image for: History Of The German General Staff 1657-1945 [Illustrated Edition]](https://img.perlego.com/book-covers/3020536/9781786254955_300_450.webp)