History

Transcontinental Railroad

The Transcontinental Railroad was a railway system built in the United States during the 19th century, connecting the east and west coasts. Completed in 1869, it revolutionized transportation and commerce by significantly reducing travel time and costs for both passengers and freight. The construction of the railroad also played a significant role in the westward expansion of the United States.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Transcontinental Railroad"

- No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- University Publications(Publisher)

Opened for through traffic on May 10, 1869, with the driving of the Last Spike at Promontory Summit, Utah, the road established a mechanized transcontinental transportation network that revolutionized the population and economy of the American West. The Transcontinental Railroad is considered one of the greatest American technological feats of the 19th century. It is considered to surpass the building of the Erie Canal in the 1820s and the crossing of the Isthmus of Panama by the Panama Railroad in 1855. It ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ served as a vital link for trade, commerce and travel that joined the eastern and western halves of the late 19th-century United States. The Transcontinental Railroad slowly ended most of the far slower and more hazardous stagecoach lines and wagon trains that had preceded it. The railroads led to the decline of traffic on the Oregon and California Trail which had populated much of the west. They provided much faster, safer and cheaper (8 days and about $65 economy) transport east and west for people and goods across half a continent. The railroads' sales of land-grant lots, and the transport provided for timber and crops, led to the rapid settling of the supposed Great American Desert. The main workers on the Union Pacific were many Army veterans and Irish immigrants. Most of the engineers and supervisors were Army veterans who had learned their trade keeping the trains running during the American Civil War. The Central Pacific, facing a labor shortage in the West, relied on mostly Chinese immigrant laborers but about one tenth were Irish. They did prodigious work building the line over and through the Sierra Nevada mountains and across Nevada to the meeting in Utah. Pacific Railroad Bond, City and County of San Francisco, 1865 The railroad was motivated in part to bind the eastern and western states of the United States together. - eBook - ePub

- Deborah Cadbury(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Harper Perennial(Publisher)

5 The Transcontinental Railroad ‘It will be the work of giants … and Uncle Sam is the only giant I know who can grapple the subject.’ William Tecumseh Sherman, 1857 I N THE EARLY PART of the nineteenth century, the vast continent of North America lay as it had for centuries, marked only by Indian and buffalo trails and the worn wagon tracks of those making the journey west. Travel across the Great Plains, wide rivers, deserts and mountain ranges was slow and dangerous, with no guarantee of safe arrival in California. Many making the journey from east to west preferred to travel by sea, braving a six-month voyage around South America’s Cape Horn, rather than attempt the hazardous overland crossing. The only other route was to cross the Isthmus of Panama and board a ship to San Francisco – risking yellow fever, malaria and other deadly diseases. Thousands never reached their destination; their bleached bones scattered across the Great American Desert or washed up on the shores of South America. At first, the railroad was not an obvious solution to these transport difficulties. In 1830, when the first American-built locomotive, Tom Thumb, was set to compete with a horse-drawn wagon racing next to the track, its boiler burst. But from modest beginnings there followed an unprecedented boom in the railroad industry. During the 1830s and 1840s many railroads sprang up in the eastern states, casting a filigree pattern of transport across the landscape and linking the east coast cities. By 1850, there were over 9,000 miles of track and this continued to be laid at a rate of over 2,000 miles a year, reaching inland to towns on the Missouri River - eBook - PDF

The Industrial Revolution in America

Iron and Steel, Railroads, Steam Shipping [3 volumes]

- Kevin Hillstrom, Laurie Collier Hillstrom, Kevin Hillstrom, Laurie Collier Hillstrom(Authors)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- ABC-CLIO(Publisher)

RAILROADS AND MANIFEST DESTINY The advent of railroads initially caused mixed reactions: to some it meant a new and potentially limitless means to economic achievement, Page 186V2 but to others it reflected the vicissitudes of modernity—the dreaded coming of the day when machine overtakes man. To these latter observers, railroads threatened to destroy the American landscape and the still fragile society emerging from the chaos and uncertainty of the nation’s violent founding. As years passed, however, the economic advantages of the railroads when compared to other transportation options, primarily steam shipping and overland routes, and their clear superiority as a mode of passenger travel over these same transportation alternatives drowned out the arguments of foes. Indeed, the railroad radically changed American perceptions of time, space, and distance. Revolutionary changes in commerce, communication, and settlement patterns followed as a matter of course, and the sheer scope of these business enterprises forced rail lines to become the first U.S. businesses to conduct their affairs on a truly continental scale. Tens of thousands of miles of railroad tracks were built across the nation during the last seventy years of the nineteenth century, tying urban metropolises and agricultural hinterlands together in a way that they had never been before. During this period, railroad tracks, rail crossings, trestles, trains of different design, depots, handcars, the rhythmic clanging of passing freight trains, and the haunting whistles of locomotives all came to assume totemic significance in the American mind. They became freighted with symbolic value, with each element emblematic of America’s growing economic power, its increasingly industrial character, and its self conscious efforts to bend the western wilderness to its will to fulfill its grand potential as an empire. - eBook - ePub

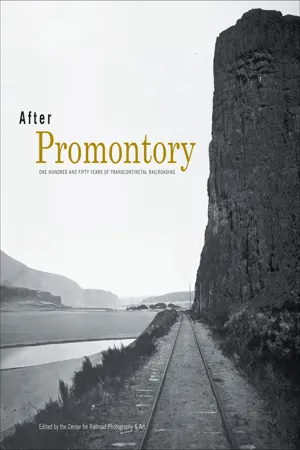

After Promontory

One Hundred and Fifty Years of Transcontinental Railroading

- Keith L. Bryant, Drake Hokanson, Don L. Hofsommer, Maury Klein, The Center for Railroad Photography & Art, Peter A. Hansen, The Center for Railroad Photography & Art, Peter A. Hansen(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Indiana University Press(Publisher)

Contrary to the term, the Transcontinental Railroads never extended from coast to coast; they marched westward from the Missouri River and relied on other lines to reach Chicago and points east. Like all Western roads, they were built ahead of demand and were expected to stimulate development of that demand. Once completed, settlers, businesses, industry, and other economic activity would follow in the railroads’ wake, traffic would increase, towns would spring up, land values would rise, and growth would spread like a fever. Or so the vision imagined. During construction, the railroad became in effect the local economy, with its insatiable needs for labor and materials.Viewed in this context, the first transcontinental was both the product of a long-held dream and an engine for economic growth with a multiplier effect. For better or worse it brought irrevocable change to the West, not only in its own presence, but as a precedent for the roads that followed and for the myriad other lines that sprouted from or connected with it. Everywhere the tracks went, life and the landscape changed. The construction work itself set this process in motion. One member of a surveying crew, young Arthur Ferguson, saw early what was happening and recorded the impression in his diary. “The time is coming, and fast too,” he noted in July 1868, “when in the sense it is now understood, THERE WILL BE NO WEST.” Some, like Ferguson, viewed the coming changes with mixed emotions; most Americans welcomed them as signs of progress and enhanced opportunities.In scale, scope, and concept, the first Transcontinental Railroad was nothing less than the grand project of the nineteenth century for Americans. Elsewhere I have likened it to the moon project of the twentieth century. On May 25, 1961, President John F. Kennedy announced a daring and expensive project to put a man on the moon within a decade. It was a bold—some said foolhardy—enterprise, made possible only by heavy financial support from the government. Despite criticism and setbacks, it too emerged as the great project of its age. After eight years of hard work and failures, it reached a brilliant conclusion in July 1969, when Neil Armstrong became the first person to step foot on the moon, while nearly half a billion television viewers around the world watched breathlessly. - No longer available |Learn more

Work Sights

The Visual Culture of Industry in Nineteenth-Century America

- Vanessa Meikle Schulman(Author)

- 0(Publication Date)

- University of Massachusetts Press(Publisher)

In this example, Wheeler used two typical rhetorical strategies of the time—a sexualized description of national expansion and a teleological understanding of technological development.27 Here the railroad violently “pierces” Colorado in order to take advantage of the ripe, fecund West, “bursting” like a womb with “mineral wealth.” Further, Wheeler suggested that technological expansion allows for continually increasing exploita-tion of resources, which, in their turn, leads to further innovations and improvements. The progress of technological systems is thus both linear and exponential. In this formulation, the system of the railroad is never complete; rather, it is ongoing, absorbing new resources into the growing prosperity of the imagined nation. Spanning the Continent Because the railroad was such a potent figure for national expansion and commerce, both professional illustrators and fine artists used it as a meta-phorical conduit spanning a massive continent. This was most evident in representations of the 1869 completion of the transcontinental line, 30 Chapter 1 when the Union and Central Pacific Railroads were united at Promontory Summit, Utah. Technological boosters had suggested the desirability of such a line beginning in the 1830s; in 1848, one author posited the hope that a Transcontinental Railroad “would make the commerce of all the world tributary to us, and make us its carriers . . . would open the wilderness to cultivation, production, and usefulness, with the best means of transit, of connexion and intercourse with all the world . . . carrying from ocean to ocean a belt of population, educated to our habits and to our institutions, which would spread its influence over the habitable globe.”28 Although they would wait more than two decades after this hopeful pronouncement, American observers eventually witnessed the line’s completion, an event that sparked an atmosphere of unqualified celebration. - No longer available |Learn more

An Economic History of the United States

Connecting the Present with the Past

- Mark V. Siegler(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Red Globe Press(Publisher)

33 Expansion after the Civil War was even more impressive. While Congress had instructed engineers to survey potential transcontinental routes in 1853, it was the Pacific Railroad Act in 1862 that led to action. The first transcontinental was the larg-est publicly-funded project of the nineteenth century. 34 The federal government pro-vided construction loans and massive land grants to two private companies: the Central Pacific, which built a railroad eastward from Sacramento, California; and the Union Pacific, which built west from Omaha, Nebraska. The transcontinental was completed on May 10, 1869, when the two rail lines met at Promontory Summit, Utah ( Figure 8.2 ). From 1865 to 1900, however, the greatest percentage of track was laid in the Great Plains states, with Chicago becoming the major terminus and St. Louis, Kansas City, Omaha, Minneapolis, and Denver becoming secondary hubs of the growing railway network. By 1910, there were 266,000 miles of main track nationwide, almost 9 times the amount in 1860. In 1910, only Canada had more rail miles per capita than the United States. 35 Chapter 8 156 Source: U.S. National Archives, www.archives.gov/global-pages/download.php?f=/historical-docs/doc-content/ images/promontory-point-utah-xl.jpg (accessed: April 21, 2016). FIGURE 8.2 The Completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad, 1869 RAILROAD OUTPUT AND PRODUCTIVITY Table 8.1 shows the growth rates of total output (freight tonnage and passenger miles) and total factor productivity for American railroads. Total output growth aver-aged 10.57 percent per year from 1839 to 1910, and output doubled roughly every 7 years. - eBook - PDF

The American West

A New Interpretive History

- Robert V. Hine, John Mack Faragher(Authors)

- 1993(Publication Date)

- Yale University Press(Publisher)

9 The Power of the Road Bret Harte, western writer and editor of the Overland Monthly, was among the crowd at Promontory, Utah, in 1869 , that witnessed the driving of the golden spike to join the tracks of the first Transcontinental Railroad. He watched as the steam engines, with overblown smokestacks and ox-sized cowcatchers, faced off for one of the most iconic photographs in American history. Harte wondered: What was it the Engines said, Pilots touching—head to head, Facing on the single track, Half a world behind each back? No one could doubt the power of the railroad to transform. Over the previous quar-ter-century it had reshaped the landscape of the eastern half of the continent, pro-pelled the country into sustained industrial growth, and made possible the victory of the Union over the Confederacy.“Railroads are talismanic wands,”one promoter wrote during the Civil War. “They do wonders—they work miracles.” What mira-cles would they work for the West? 1 Certainly hopes were high. “The iron key has been found to unlock our golden treasures,”gushed the editor of the Helena Independent . “With railroads come pop-ulation, industry, and capital, and with them come the elements of prosperity and greatness to Montana.”Once it was in place, the national railroad system would un-dergird a fabulously valuable exchange of people and products between East and West. Thousands of settlers would steam onto the plains and over the mountains to the Pacific coast, settling on farms, ranches, and in dozens of rapidly growing cities and towns, scattered like oases across the western countryside. The late nineteenth-century West was inconceivable without the railroad. “The West is purely a railroad 274 - eBook - ePub

- Frederick Arthur Ambrose Talbot(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Otbebookpublishing(Publisher)

Development is still being maintained; new territories are being conquered. A new long and sinuous arm, 3,556 miles from end to end, is being stretched out from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean, to bring the eastern into direct touch with the western seaboard. The whole has grown from the insignificant little wooden road that was laid between La Prairie and St. John’s in the Province of Quebec eighty years ago.Passage contains an image

CHAPTER V THE FIRST TRANS-CONTINENTAL ACROSS THE UNITED STATES

“There were difficulties from end to end: from high and steep mountains; from snows; from deserts where there was a scarcity of water, and from gorges and flats where there was an excess; difficulties from cold and heat; from a scarcity of timber and from obstructions of rock; difficulties in keeping a large force on a long line; from Indians; and from want of labour.”This was the terse story related to the United States Congress by Collis P. Huntington, one of the moving spirits of what, at that time, was a tremendous undertaking—the construction of the first railway across North America whereby the Atlantic was linked with the Pacific by a bond of steel. But that concise statement concealed one of the most romantic stories in the history of railway engineering: of grim battles every hour either against the hostile forces of nature or of mankind.It was in 1863 that the first sod was turned in the construction of the first line which was destined to bring San Francisco within 120 hours’ journey of New York, and which changed completely the whole stream of traffic flowing round one-half of the northern hemisphere. But for some years before the spade was driven into the earth to signal the commencement of this enterprise, the idea had been contemplated and discussed in a more or less academic manner. It was such a vast scheme, the commercial possibilities of success appeared so slender that the most daring financiers of that day shrank from fathering it. Capitalists concluded that they might just as well pour their money down a well as to sink it in such a project as this. - eBook - ePub

- Elizabeth B. Greene(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

Manifest Destiny, the widespread belief during the 19th century that the expansion of the United States from “sea to shining sea” was not only justified but also inevitable, was coined in 1845 by influential journalist John L. O’Sullivan while advocating for the annexation of Oregon and Texas. The relief valve that the opening of the West represented lured thousands of eager settlers to pack up their prairie schooner wagons and make the treacherous journey on wagon trains that lumbered along the Oregon or Santa Fe Trail. The perilous trip took six months and had to be started in the spring, so it could be completed before the onset of the winter. Such risk didn’t deter these hardy souls from venturing out, but the situation would soon be transformed when the Transcontinental Railroad opened in 1869. Railroad lines had already been built along the East Coast beginning in the 1830s, and the South and Midwest were connected by networks of railroads by the 1840s. California was annexed in 1848 after the Mexican-American War, the same year that gold was discovered there. The region soon became a magnet for fortune-seekers and settlers. In 1850, California joined the union as the 31st state. Congress began investigating the possibility of building a railroad to California. In 1853, Congress appropriated funding for the Army Topographic Corps “to ascertain the most practicable and economical route for a railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean.” Surveyors were sent out to investigate four separate routes, and debates took place regarding the advantages of a northern or southern route. No matter which route they opted for, any Transcontinental Railroad would require risky and dangerous construction over an intimidating landscape of mountains and deserts. The task was daunting, but despite the Civil War that was raging, President Abraham Lincoln advocated for the railroad to be built, and on July 1, 1862, he signed the Pacific Railway Act. This legislation authorized land grants and government bonds to two companies, the Central Pacific Railroad and the Union Pacific Railroad, to lay the track for the country’s first Transcontinental Railroad, with the Central Pacific Railroad coming from the west and the Union Pacific Railroad coming from the east. They would meet at the middle.Description

This 1869 official poster announced the grand opening of the first Transcontinental Railroad. The ceremony took place on May 10, 1869, at Promontory Summit near Ogden, Utah. The poster, printed by the Union Pacific Railroad, was more of an advertisement for the rail service than an invitation to the ceremony. The text of the poster, loaded with rapturous promotion of the service and the ceremony, states the following: - eBook - PDF

American Railroads

Decline and Renaissance in the Twentieth Century

- Robert E. Gallamore, John R. Meyer(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Harvard University Press(Publisher)

1 1 TH E E N D U R I N G A M E R I C A N R A I LROA DS [There] was made on February 1, 1804, the combination of locomotive engine power pulling a train of cars on tracks, which is the foundation of the railroad as we know it. The power was provided by a high-pressure steam locomotive, built by Richard Trevithick. The cars were loaded with minerals for the iron works at Merthyr Tydfil, in South Wales. The track was the plate way of the Pennydarran Tramroad, newly laid with flanged rails. — ROBERT SEL PH HEN RY (1942) . . . [I]n 1829, Stephenson made the locomotive a success. The next year saw the introduction of the railway into America, and two years later there was published an article proposing a railway to the Pacific. — HEN RY K IR K E W HI T E (1895) Railroads are one of the great industrial achievements of modern civilization. It is impossible to imagine the building of our Nation’s commercial and military strength without the railroads. Railroading has a proud tradition, and the industry remains an indispensable part of our economy. — F EDER A L R A I L ROA D A DM I N IST R AT ION (1978) A merican Railroads is the story of a great industry that dominated US freight transportation over land at the beginning of the twentieth cen-tury, lost its leadership and much of its economic power over the next eighty years, and then, almost miraculously, was reborn in the last two decades of the century. We characterize railroads as enduring because as the century wore on, they survived more than they dominated their rivals. They persisted as a fundamental part of the US freight transportation system more than they succeeded financially. A M E R I C A N R A I L R O A D S 2 At the turn of the twentieth century and for decades before and after, railroads became a frequent topic of newspaper and parlor debate. - eBook - PDF

- W.T. Easterbrook, Hugh Aitken(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- University of Toronto Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER X V I I I THE TRANSCONTINENTAL RAILWAYS RAILWAYS AND CONFEDERATION: THE INTERCOLONIAL THE confederation of the maritime provinces and central Canada in 1867, the purchase of Rupert's Land in 1869, and the admission of British Columbia to the federation in 1870 brought into being a new nation in North America. Political union, however, stood little chance of survival unless it was complemented by economic union. This was necessarily a slow and difficult process. It was not enough merely to abolish tariffs between the provinces and interpose tariffs between them and the outside world. The tariff as an instrument of economic development could not be effective unless the various regions of Canada, with their diverse resources, could specialize in those types of production for which they had differential advantages. Such regional specialization depended upon the creation of transportation facilities which would permit products and labour to move cheaply and easily from one part of the country to another. Economic unification, in a word, depended upon the improvement of communications, and specifically upon the construction of railways. Two railway projects in particular were indispensable. One was the construction of a line between central Canada and the Maritimes, the other the construction of a line from central Canada across the western prairies to the Pacific coast. The first of these lines had been insisted upon by the maritime provinces, the second chiefly by central Canada, though it also had strong support in British Columbia. It was considered essential that both lines should pass wholly through Canadian territory, partly for strategic reasons, partly through fear that traffic would be diverted over American routes. Since 1852, when negotiations for joint construction of an intercolonial railway had ended in deadlock, the maritime provinces and central Canada had followed independent policies of railway construction.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.