History

Warren Court

The Warren Court refers to the period when Earl Warren served as Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1953 to 1969. This era is known for its landmark decisions that significantly shaped American constitutional law, particularly in the areas of civil rights, criminal justice, and individual liberties. The court's rulings had a lasting impact on American society and legal jurisprudence.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Warren Court"

- eBook - PDF

Rights vs. Responsibilities

The Supreme Court and the Media

- Elizabeth B. Hindman(Author)

- 1997(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

Chapter Three The Warren Court Years, 1953-1969 Republican Earl Warren, former vice presidential candidate (1948) and governor of California, became chief justice on October 5,1953, less than a month after Chief Justice Fred Vinson's death. He had no judicial experience; his appoint- ment was "purely political," meant to appease liberal Republicans criticizing President Eisenhower's links with more conservative party members. 1 His views on social issues and the judiciary were not well known, other than his pro-state sovereignty statements as California governor (which he later came to regret) and his work as a district attorney concerned with law enforcement 2 He was meant to be a moderate chief justice, White writes, but "came . . . possessed of a strong belief in the worth of active government... The fact that he had no well-devel- oped philosophy of judging was in his case of no consequence; he had instead a well-developed philosophy of governing." 3 Warren's belief in the ultimate value of fairness and equality guided him, and the Court under his direction, for four- teen years. Warren served with sixteen associate justices over the fourteen years, a group that included some of the most brilliant justices of the century. Hugo Black and Felix Frankfurter continued their battles of earlier years, William O. Douglas fought for libertarian ideals, and John Marshall Harlan, II, took up Frankfurter's restraintist banner, but with more conservative colors. By the mid-1950s, the Court was evenly split between liberals and conservatives, with Warren, Douglas, Black, and William Brennan on one side and Harlan, Frankfurter, Harold Burton, and Stanley Reed on the other. Tom Clark occupied a moderate position.+ The Warren Court underwent several phases, from this even split in the early years, to a retreat to (moderate) conservatism in the late 1950s, to a def- inite liberal phase in the mid and late 1960s. Throughout it all, h conflicts formed in earlier years c - eBook - ePub

Father, Son, and Constitution

How Justice Tom Clark and Attorney General Ramsey Clark Shaped American Democracy

- Alexander Wohl(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- University Press of Kansas(Publisher)

1 For the rest of Tom Clark’s eighteen years on the Supreme Court, he would serve alongside Warren, developing a strong working relationship and a friendship at least as close as the one he had with Vinson. The two would go on hunting and fishing trips together, socialize together with their wives, and for a good portion of their combined tenure even walked the several miles in to work together. More significantly, Clark would forever be a part of one of the most influential and brilliant collections of minds (but not always harmonious personalities) to constitute the high court. Collectively, but certainly not always unanimously, the Warren Court transformed American society from one based largely on the protection of property rights to one focused on the defense of personal and civil rights. It would produce expansive interpretations of the Constitution that revolutionized the way Americans interact with their government and think about a broad range of issues central to our personal and professional interactions, behaviors, rights, and liberties, ultimately helping to enhance the definition of individual rights in a way most Americans now accept as standard.Though by no means either the spiritual or the intellectual leader of the Warren Court, Clark nonetheless evolved into an integral part of it, writing decisions that were central to its legacy of enhanced individual rights while balancing the Court’s broad egalitarian goals with his own general conservative nature and principles of judicial restraint. During his tenure, Clark’s judicial philosophy was often hard to pigeonhole; he was neither an absolutist on judicial restraint like Felix Frankfurter nor a liberal activist like William Douglas. Much like the law that he and his Brethren interpreted and applied, Clark’s views evolved during his tenure on the bench and the ten years of his life after that when he heard cases on numerous lower federal courts.Race and Equal RightsThe most profound part of the Warren Court’s individual rights legacy was its embrace and elucidation of the Constitution’s principles of racial equality. In this regard, Clark exhibited little equivocation, supporting civil rights efforts as he had both as attorney general and in his early tenure on the Court. He was consistently a member of the Court’s majority in civil rights cases that built on the Vinson Court’s rulings such as Sweatt v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents. The most momentous of these opinions were the 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which found segregation in public schools unconstitutional, and the less well known Hernandez v. Texas, in which the Court ruled that excluding persons of Mexican ancestry from juries violated the Constitution, the first Court decision to strike down discrimination against a nonblack minority.2 - eBook - ePub

Principled Judicial Restraint: A Case Against Activism

A Case Against Activism

- Jerold Waltman(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Pivot(Publisher)

Justice in 1953 when Chief Justice Fred Vinson died suddenly. Most scholars contend that the Warren Court can be divided into two eras: 1953–1962 and 1962–1969. During the first of these the central case is, of course, Brown v. Board of Education. 26 Aside from Brown, the Court could not be said to be especially activist in these early years. However, beginning in 1962, with the retirements of Justices Charles E. Whittaker and Felix Frankfurter and their replacement with Byron White and Arthur Goldberg (later himself replaced by Abe Fortas), nothing short of a revolution in judicial activism took place. In short, liberal activism became completely triumphant. If we adopt the thesis that the Court stays largely in step with the main outlines of the political consensus of the day (even though there may be a lag), this was hardly an aberration. 27 Liberalism was the dominant political ethos from the New Deal to the Great Society. 28 Because we will consider Brown more fully in a subsequent chapter, we will concentrate for the moment on the 1962–1969 period. As but one measure of the changes wrought, during the Warren Court years 45 precedents were overruled; in contrast, only 88 had been overturned by the Supreme Court in all the years before then. As another, the sheer scope of the major decisions the Court handed down seem staggering, touching criminal justice, free speech, welfare rights, church–state relations, privacy, and legislative reapportionment. But equally important were the rationales the Court employed. In short, the guiding principle of the Warren Court was “Is it fair?” Once something was deemed to be “fair” and “right,” the opinions of the Court brazenly detached themselves from the traditional moorings of legal justifications. This is not to say that no Court had done this before; however, none had done it so often and so forthrightly. The extreme case is Justice Abe Fortas - eBook - ePub

In the Shadow of the Great Charter

Common Law Constitutionalism and the Magna Carta

- Robert M. Pallitto(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- University Press of Kansas(Publisher)

Earl Warren became chief justice in 1953 as the Supreme Court prepared to hear a second round of arguments in the desegregation cases consolidated under Brown v. Board of Education, and before the Court had rendered a decision in the cases. Warren served as chief justice from 1953 to 1969, during which time the Court announced its historic ruling in Brown and also issued numerous rulings in enforcement of Brown’s holding that state-enforced racial segregation of public schools violated the Fourteenth Amendment. In addition to the monumentally important equal protection precedent represented by Brown, the Warren Court’s other principal legacies were its protection of voting rights and its incorporation of Bill of Rights provisions into the Fourteenth Amendment so that those provisions applied against the states as well as the federal government (for instance, Mapp v. Ohio established that evidence seized in violation of the Fourth Amendment was barred from use in state as well as federal criminal prosecutions). In these areas—equal protection, voting, and incorporation of the Bill of Rights—the Warren Court changed the course of constitutional interpretation in ways that broadened individual rights protections for vulnerable individuals and groups: African American students, speakers holding unpopular views, and criminal defendants, among others. Some viewed this “rights revolution” as an unprincipled and result-oriented expansion of judicial power. They believed that the Court’s focus on justice for the groups mentioned earlier came at the expense of the institutional and doctrinal limits previously observed and also diminished the Court’s integrity and legitimacy. Others—myself included—find the same developments to be salutary and readily explainable within the development of common law constitutionalism. I will argue in this chapter that the Warren Court continued key aspects of that tradition, particularly in its flexible application of precedent and its commitment to using constitutional concepts to promote equality as a deep social value. Some of the criticisms are misplaced, I will argue, because they rely on the assumptions of formalism that were discredited by the Legal Realists in the decades preceding Earl Warren’s ascension to the bench. To require or expect courts to ignore the larger social consequences, or what Holmes called the “social advantage,” of a particular ruling is a relic of the formalistic approach to legal analysis. As the Court construed the meaning of “equality” under the Fourteenth Amendment, for example, it took into account the effect of decades of Jim Crow laws and practices on black Americans. This broader perspective allowed the Court to outlaw segregated schools even though the history of the Fourteenth Amendment did not indicate that its passage was meant to do so. - eBook - ePub

Judicial Review and Judicial Power in the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court in American Society

- Kermit L. Hall(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

But it would be inaccurate to lump all of the critics of the Warren Court with the late Senator Byrd or to characterize all of the criticism as wholly irresponsible. Self-serving office seekers and hot-headed extremists have not been the only groups dissatisfied with the work of the Court. Forceful challenge has also come from legal scholars and other students of constitutional adjudication.II. The Voice of the Critics

In the vanguard of this latter group, Professor Philip B. Kurland recently wrote that during the “fateful decade” between 1954 and 1964, “a period almost coincidental… with the presence on the Court of Mr. Chief Justice Warren… the Justices have wrought more fundamental changes in the political and legal structure of the United States than during any similar span of time since the Marshall Court had the unique opportunity to express itself on a tabula rasa .”4 And, just a few months ago, Professor Kurland evidenced no reluctance to extend his charge through the three years following 1964.5What of his assertion? First, it would be foolhardy to deny that the Warren Court has rendered an impressive number of significant decisions—not just a few breaking new ground or reversing doctrines thought to be inconsistent with developing societal values and emerging human demands under a “living” constitution, a document constructed to assure flexibility in the administration of government for centuries, as well as continuity.6 (It is well to recall that it is the Constitution, not the Internal Revenue Code, that the Court is expounding. The insight of Chief Justice Marshall, “ … that it is a constitution we are expounding,”7 although not subject to easy, explicit or concise explanation, was referred to by Mr. Justice Frankfurter as “the single most important utterance in the literature of constitutional law—most important because most comprehensive and comprehending.”8 ) One need only mention such cases as Brown v. Board of Education ,9 Baker v. Carr 10 and Reynolds v. Sims ,11 Engel v. Vitale 12 and School District v. Schempp ,13 Mapp v. Ohio 14 and Miranda v. Arizona ,15 New York Times Co. v. Sullivan ,16 and Katzenbach v. Morgan 17 to acknowledge the pace of the Warren Court.III. The Vinson and Stone Courts

- eBook - PDF

Constitutional Politics in a Conservative Era

Special Issue

- Austin Sarat(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- JAI Press Inc.(Publisher)

UNDERSTANDING THE IMPACT AND VISIBILITY OF IDEOLOGICAL CHANGE ON THE SUPREME COURT Scott E. Lemieux and George I. Lovell ABSTRACT This chapter offers an explanation for the mixed record of the Supreme Court since the 1960s, and considers the implications of that record for the future. The chapter emphasizes that judicial power is connected to choices made by other political actors. We argue that conventional ways of measuring the impact of Court rulings and the Court’s treatment of precedents are misleading. The Court cannot be understood as a counter-majoritarian protector of rights. In both past and future, electoral outcomes determine the policy areas in which the Court will be influential, and also the choices the justices make about how to portray their treatment of law and precedents. Special Issue: Constitutional Politics in a Conservative Era Studies in Law, Politics, and Society, Volume 44, 1–33 Copyright r 2008 by Emerald Group Publishing Limited All rights of reproduction in any form reserved ISSN: 1059-4337/doi:10.1016/S1059-4337(08)00801-6 1 INTRODUCTION: RIGHTS, MAJORITIES, AND Warren Court HANGOVERS Earl Warren was Chief Justice for fifteen years, and left the Supreme Court almost forty years ago. Yet the constitutional scholarship inspired by the Warren Court continues to haunt both scholarly and popular under-standings of the Supreme Court. Landmark liberal rulings during Warren’s tenure inspired seminal works in constitutional theory that introduced the terminology and theoretical constructs that many scholars continue to use as they try to understand the ongoing role of the Court in the political system. The scholars inspired by Warren’s tenure often applauded the liberal direction of the Court and developed faith in the Court as a positive force for social change. However, they also worried that unelected judges were making policy rather than elected officials. - eBook - ePub

The Supreme Court and McCarthy-Era Repression

One Hundred Decisions

- Robert M. Lichtman(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- University of Illinois Press(Publisher)

As a justice, he combined traditional values—his “great strength,” Justice Potter Stewart observed, “was his simple belief in the things that we now laugh at: motherhood, marriage, family, flag, and the like”—with the skills and insights of a successful politician. “Warren’s forte,” Bernard Schwartz wrote, “was not so much intellect as it was leadership.” While never a scholar, he became an outstanding chief justice—“the Super Chief,” his colleague William J. Brennan Jr. termed him—due to his uprightness and ability to lead and persuade. His offhand (perhaps simplistic) remarks at a farewell party in Sacramento revealed his sympathies: “I am glad to be going to the Supreme Court because now I can help the less fortunate, the people in our society who suffer, the disadvantaged.” “Most often,” Anthony Lewis wrote, “his sympathy lay with the individual victims of governmental restraints.” 5 Before joining the Court, Warren, in one biographer’s view, had been “as militant an anti-Communist as those he associated with McCarthyism.” But on the Court, he saw at first hand the impact of an overwhelmingly anti-Communist public opinion on the civil liberties of individuals. Guided at the outset by Frankfurter, he was initially hesitant in “Communist” cases. But within a few years, he “moved toward Black and Douglas,” Michal Belknap wrote, “beginning to exhibit the concern for individual rights that would become the hallmark of the Warren Court.” 6 Warren’s first two Court terms were dominated by the school-desegregation cases— Brown I in May 1954, holding racial segregation in public schools violative of the Equal Protection Clause and, a year later, Brown II, ordering that desegregation proceed with “all deliberate speed”—and marked by a diminution, temporary only, in the number of decisions in “Communist” cases - eBook - PDF

The Warren Court

Justices, Rulings, and Legacy

- Melvin I. Urofsky(Author)

- 2001(Publication Date)

- ABC-CLIO(Publisher)

Much of the debate in the 1980s and 1990s over the efficacy of courts acting as agents of change grew out of the efforts to make, as the first Justice Harlan put, a Constitution that is truly colorblind. It was perhaps inevitable that Brown raised hopes it could not fulfill. No one case—not even a series of cases—could overcome the deepseated racism that has become institutionalized in American society. Jack Greenberg, who worked with Thurgood Marshall on Brown and who succeeded him as head of the Legal Defense Fund, wrote on the fortieth anniversary of the landmark decision that “altogether, school desegregation has been a story of conspicuous achievements, flawed by marked failures, the causes of which lie beyond the capacity of lawyers to correct. Lawyers can do right, they can do good, but they have their limits. The rest of the job is up to society.” One can substitute “courts” for “lawyers,” and the conclusion is still the same. The Burger Court and Speech The Warren Court, despite some notable decisions expanding freedom of expression, had never developed a comprehensive First Amendment jurisprudence. The Burger Court thus inherited a variety of precedents without the luxury, as it were, of a specific theory that it could either advance or reject. The noted First amendment scholar Thomas Emerson complained that at various times the Warren Court had used such Page 209 diverse tests as bad tendency, clear and present danger, incitement, a variety of ad hoc balancings, vagueness, overbreadth, and prior restraint, but it had “totally failed to settle on any coherent approach’’ (Emerson 1970, 15–16). In analyzing the Warren Court’s impact, especially in First Amendment areas, it must be understood that some issues, such as the intractable obscenity problem, may just not be amenable to simple formulas. - eBook - ePub

Liberty and Union

A Constitutional History of the United States, concise edition

- Edgar J. McManus, Tara Helfman, Edgar McManus(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Figure XXI.1 The Warren Court. Back Row (L to R): Tom Clark, Robert H. Jackson, Harold Burton, and Sherman Minton. Front Row (L to R) Felix Frankfurter, Hugo Black, Earl Warren, Stanley Reed, and William O. Douglas.Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-113496New Priorities

Warren soon made it clear that he was a judicial activist who believed that the Court had a role to play in shaping public policy. His views on the nature of judicial responsibility were by no means novel. The Court took an activist stance in the late nineteenth century and during the 1920s in protecting property rights against state and federal regulation. Judicial activism fell into disrepute during the New Deal era in the thirties and forties, and the Court ceased overturning social and economic legislation on policy and philosophical grounds. Liberal jurisprudence since the New Deal held that the Court should apply the law and not make it. But liberal faith in judicial self-restraint began to wane in the Cold War years when governmental power fell into the hands of conservatives and reactionaries. Loyalty programs and political witch hunts went unchallenged partly because of the view that the justices should not second-guess the policy decisions of elected lawmakers. Liberals now came to regard judicial self-restraint as an abdication of responsibility, a Pontius Pilate approach to the administration of justice that allowed judges to wash their hands of difficult issues.Warren revived judicial activism but reversed its priorities. He shifted its focus from the protection of property and business to the protection of liberty and individual freedom. Government would still be given the benefit of the doubt with respect to social and economic regulation, but restrictions on personal freedom would be closely scrutinized. This of course amounted to a double standard of the sort followed in the late nineteenth century when the Court struck down economic regulations but turned a blind eye to measures abridging the civil rights guarantees of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. Warren’s double standard turned things around: liberty and personal freedom were in, and property rights were out. The latter could be regulated by government with minimal judicial interference, but the former would be protected to a degree unprecedented in the history of the Court. - eBook - ePub

Liberty and Union

A Constitutional History of the United States, volume 2

- Edgar J. McManus, Tara Helfman, Edgar McManus(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

XXI Earl Warren Takes the Helm “It is the spirit and not the form of law that keeps justice alive.” —Chief Justice Earl Warren, Fortune Magazine (Nov. 1955) When Chief Justice Vinson died in 1952, President Eisenhower replaced him with Governor Earl Warren of California. Warren came to the Court with one of the most remarkable records in the history of California state politics. After serving as an assistant and then county attorney, he was elected district attorney, state attorney general, and finally governor of California. Although a Republican, he was as popular with Democrats as with members of his own party. Warren was the only person elected to three successive terms as governor. Nominated for the vice presidency in 1948, he went down to defeat with Thomas E. Dewey in Truman’s upset victory. Had Dewey won, it is highly unlikely that Warren would have gone on to become chief justice. In that case, our constitutional history would have been different, perhaps as different as it would have been had President Adams not appointed John Marshall to the Court. No chief justice, with the exception of Marshall, has had a greater impact on our constitutional system. Justice Jackson died in 1954, and his place was taken by John Marshall Harlan, grandson of the great dissenter in Plessy v. Ferguson. Harlan had practiced law for many years before being appointed to a federal circuit judgeship by Eisenhower in 1954, just one year before being elevated to the Supreme Court. Although not a particularly active Republican, he had the support of Dewey and other important party leaders. It was an excellent appointment. Harlan’s intellectual distinction and independence of mind and judgment were just the qualities needed on the Court. Gifted with a clear, incisive writing style, he was a fitting successor to Jackson - eBook - ePub

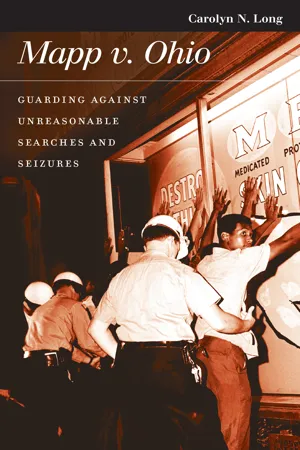

Mapp v. Ohio

Guarding against Unreasonable Searches and Seizures

- Carolyn N. Long(Author)

- 2024(Publication Date)

- University Press of Kansas(Publisher)

There are different theories as to why the Warren Court so aggressively focused on the rights of criminal defendants. Some observers saw the decisions as part of the Court’s broader effort to ensure equal justice for all Americans, including criminal defendants. They note that its criminal procedure decisions should be read along with its opinions dealing with race because the Court aimed to address injustices felt primarily in communities of color. Others saw the criminal due process revolution as inevitable because of the inability of state legislatures to address law enforcement abuses in their own courts. Still others suggested that the federalization of criminal procedural rights was the result of the justices’ personal experience with police misconduct and the inability of state courts to stop these abuses. Chief Justice Earl Warren, a former prosecutor, would himself characterize these decisions as an attempt to professionalize police and ensure more effective law enforcement. In his 1972 book, A Republic, If You Can Keep It, he explained that the decisions were aimed at ridding law enforcement of its coercive and unethical features and addressing procedural flaws in a system that disadvantaged criminal defendants. “We must have vigorous enforcement of the law, but that enforcement must be fair, equal in its application, and in accordance with our time-honored and loudly professed freedoms.” All revolutions attract their share of critics, and the Warren Court’s criminal procedure revolution was no different. Some targeted the Court’s use of the selective incorporation doctrine as inappropriate because it had no basis in history or law. Even those supportive of the decisions in principle called attention to the Court’s undisciplined approach and its inability to justify its activism

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.