What is Rococo?

PhD, Media Arts (Royal Holloway, University of London)

Date Published: 16.01.2024,

Last Updated: 16.07.2024

Share this article

Defining rococo

Throughout history, the question of the purpose of our lives has persisted. Rococo, sometimes referred to as the “late baroque,” is an art movement and design aesthetic that provides an answer to this question. According to rococo, life was all about the pursuit of pleasure. Emerging in France in the early to mid-18th century, it was playful, scandalous, and above all, hedonistic. Rococo reflected the values of an aristocracy that was flirtatious, boozy, and extravagant, representing the heights of sensory indulgence. But how did art of this nature rise to prominence, and what do these values look like as an aesthetic?

The word rococo is derived from the French “rocaille,” referring to irregular-shaped pebbles and seashells. Rocaille was a Renaissance design style in itself whereby pebbles and seashells were arranged in plaster as ornamentation. Rococo was a tongue-in-cheek spinoff of rocaille. The term was credited to neoclassical painter Pierre-Maurice Quays (1777–1803) who invented the word around 1797 to poke fun at the already-established excessive aesthetic. Rococo exhibited the same motif of natural, organic, sometimes unruly forms as rocaille but with even less balance and symmetry and even more extravagance.

Rococo involves an abundance of natural forms. Gold and silver vines, leaves, flowers, and animals adorn rococo ornamentation and architecture. Rococo paintings feature figures in floaty, pastel colors against rich foliage or lavishly decorated interiors, creating a sense of opulence and joy. The rococo aesthetic was particularly prevalent in the decorative arts. With furniture, sculpture, and décor being some of the most recognizable works of rococo, it was an aesthetic taste that was primarily expressed in homes, in private, secular spaces. Linda Walsh describes what this looked like:

The rococo style was characterized in interior décor by white panels, gilded frames and cartouches, and abundant decorative plaster work; shiny satins, brocades, silks and flocked wallpapers, some imported from China and the Far East; and sparkling mirrors decorated with C‐scroll, palm and ribbon motifs. (A Guide to Eighteenth-Century Art, 2016)

Linda Walsh

The rococo style was characterized in interior décor by white panels, gilded frames and cartouches, and abundant decorative plaster work; shiny satins, brocades, silks and flocked wallpapers, some imported from China and the Far East; and sparkling mirrors decorated with C‐scroll, palm and ribbon motifs. (A Guide to Eighteenth-Century Art, 2016)

Rococo was sensual, indulgent, and fun. Its subject matter was lighthearted with the intent to celebrate the pleasures and fineries of life. This study guide will explore how these tastes came to be and the way that these effects were achieved.

Historical context of rococo

There were two main aesthetic movements that preceded rococo: classicism and baroque. Classicism was a style prevalent during the Renaissance, inspired by ancient Greco-Roman culture. Classicist tastes were refined, symmetrical, and restrained, exhibiting the achievements of imperial civilization. This was replaced by baroque in the early 17th century, precipitated by the Protestant Reformation. Baroque was a movement commissioned by the Catholic Church to emotionally engage with the church-going public. To this end, baroque was highly emotional – frightening even – with strong religious imagery.

Despite sometimes being considered the final iteration of baroque, rococo was stylistically quite different. The purpose of baroque was to instill faith in the masses; it was dark, tense, and violent. By contrast, rococo was light and fanciful, concerned with the frivolous occupations of the aristocracy. Rococo pushed back against the weight and seriousness of baroque; against art as a moral or religious vessel. But why did these aesthetic tastes shift?

In 1715, the King Louis XIV of France died. His tastes were extravagant, incorporating strong elements of classicism and baroque and leaving behind one of the most impressive courts in Europe. Centering around the Palace of Versailles, the architecture and decorative arts that characterized Louis XIV’s reign were predominantly balanced and symmetrical, exhibiting the triumphant precision of classicism. During this time, artists had to conform to this aesthetic taste.

After the death of King Louis XIV, tastes began to change. This was in large part because the aristocracy moved from the rural setting of Versailles – the locus of political and economic power – and into the bustle of Paris. This shift of focus from the monarchy to the lives of the aristocrats brought about much social and political change and ushered in the rococo movement.

This move into the city facilitated more privacy for the ruling class; rather than the chambers in the Palace of Versailles, they lived in large town houses, replacing public court life with more intimate meeting spaces. This was reflected in the surge of decorative ornamentation in fashion and living quarters. In Paris, surrounded by thinkers who might threaten the power of the aristocracy – as well as the general dirt and squalor of metropolitan living – the nobility had even more reason to turn in towards the lavish privacy of their homes. These salons played host to all sorts of gossip, drinking, lust and romantic escapades, as well as conversations on art, politics, and literature. These impulses and ideas are reflected in the subject matter of rococo.

To this end, rococo expressed the lighthearted and hedonistic escapism of the ruling classes. It was playful and erotic – subverting courtly decorum – and it was lavish, celebrating the luxurious and leisurely occupations of the aristocracy.

The rococo style

There are several key characteristics of the rococo style that make it immediately recognizable in all its forms:

- Pastel colors

- Scandalous subject matter

- Depictions of love, lust, and courtship

- Nature and organic motifs

- Intricate details

- Rapid brushstrokes

- Eastern influences

- Mythology

- Asymmetry

Rococo often depicted scenes in nature, with delicate floral and faunal designs, providing another layer of whimsical escapism for the French elite in metropolitan Paris. Many of these organic motifs referenced exotic animals and foliage inspired by the far East known as “chinoiserie.” Popularized in Europe through the East Asian Trade, Chinese, and Japanese ornamental aesthetics became a notable component of rococo alongside iconography from closer to home. These motifs were found in porcelain and jade finery, featuring in frescoes and adorning cornices. In A Companion to Renaissance and Baroque Art, Larry Silver expresses this development,

Rather than sixteenth-century fear and/or fascination concerning a rival power, the Rococo era blended Turkish motifs with other unthreatening, foreign exotica – equivalent to East Asian chinoiserie or compliantly picturesque African servants – in eighteenth-century luxury decorative objects, including porcelains, or interiors. (“Europe’s Golden Vision,” 2012)

Edited by Babette Bohn and James M. Saslow

Rather than sixteenth-century fear and/or fascination concerning a rival power, the Rococo era blended Turkish motifs with other unthreatening, foreign exotica – equivalent to East Asian chinoiserie or compliantly picturesque African servants – in eighteenth-century luxury decorative objects, including porcelains, or interiors. (“Europe’s Golden Vision,” 2012)

This provides an example of the imaginative lives of the aristocracy, whose fancies transported them to “exotic,” faraway lands.

With the aristocracy now establishing themselves as the arbiters of arts and culture, artworks turned away from religion and morality towards the fantasies of everyday life. As Walsh summarizes,

The adoption of “gallant” rococo subjects and styles of decoration, aiming to entertain the eye with their profusion of graceful curves, gold and white, pastel shades, gleaming mirrors and reflected candle light, served as a means of establishing moral and social authority independently of court favor and appointments, and as a means of negotiating one’s cultural status within evolving social groups or “classes” of the wealthy. Distancing themselves from mythic visions of public military or political power (traditional themes in grand history painting), the concerns of aristocrats with new, social forms of influence became displaced to the realms of gallantry and the “conquests” of love, in which they sought more private forms of cultural validation. (2005)

In this way, rococo was commissioned by, and appealed to, the nobility of 18th century France.

Rococo paintings

The first painter to create works in the style of rococo was Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721) with his painting, The Embarkation for Cythera (1717) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1, Jean-Antoine Watteau (1717) The Embarkation for Cythera [oil on canvas] (uploaded by Sailko, 2013, Wikimedia Commons; CC BY 3.0)

This work was his debut to the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture), an institution at the forefront of aesthetic fashions in France. The painting depicts a mythological landscape with cherubs flying overhead, strewn with wealthy men and women courting and celebrating. This work did not fit into any of the existing genres of art, so the Academy created a new one characterized by the depiction of wealth, leisure, and joy. This new genre was immediately supported by the aristocracy – the locus of economic power at the time – and rococo rose to prominence.

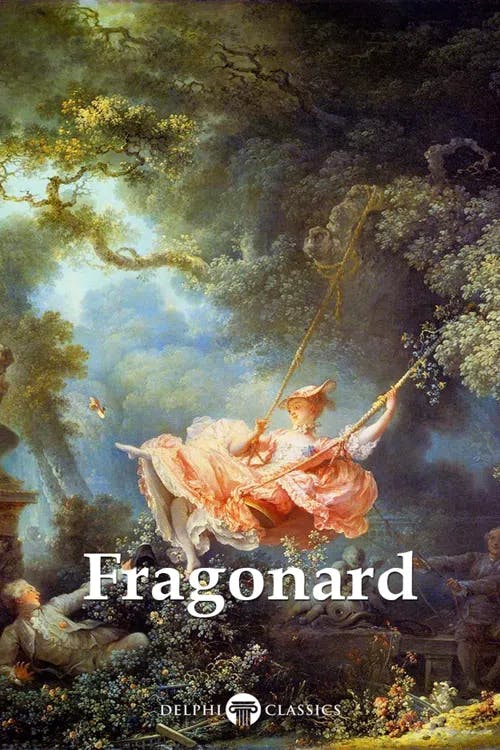

When you look for examples of rococo painting however, one image looms large: The Swing, or The Happy Accident of the Swing (1766) by Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806)(see Figure 2).

Figure 2, Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1766) The Swing (used under CC0 1.0)

Fragonard was torn between a more serious, religious, and historical form of art and the new, lighthearted aesthetic fashions. But, as Peter Russell explains,

It was the demand of the wealthy art patrons of Louis XV’s pleasure-loving and licentious court that would in the end turn him definitely towards the scenes of love and voluptuousness with which his name will be forever associated. (Delphi Complete Works of Jean-Honoré Fragonard, 2018)

Edited by Peter Russell

It was the demand of the wealthy art patrons of Louis XV’s pleasure-loving and licentious court that would in the end turn him definitely towards the scenes of love and voluptuousness with which his name will be forever associated. (Delphi Complete Works of Jean-Honoré Fragonard, 2018)

The Swing was borne out of this demand. It shows a young woman in plumes of pastel-coloured fabric perched in mid-air on a swing. Her shoe floats in the air as if she has just kicked it off, giving the whole painting a sense of weightlessness. (For more images and analysis of Fragonard’s work, please see Russell’s Delphi Complete Works of Jean-Honoré Fragonard, 2018.)

Fragonard's paintings were a far cry from the baroque, where a quintessential work of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1517–1610) depicted the heavy body of a dying Christ (see Figure 3).

Figure 3, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1603) The Entombment of Christ [oil on canvas] (under CC0 1.0)

Comparing the painting styles of Fragonard and Caravaggio, the difference between rococo and baroque are immediately noticeable. As Arnold Hauser writes of the emerging rococo style,

The tendency towards the monumental, the ceremonious and the solemn already disappears in the early rococo and makes room for a more delicate and intimate quality. In the new art preference is given to colour and shades of expression rather than to the great, firm, objective line and the note of sensuality and sentiment is to be heard in all its manifestations. (Social History of Art, 2005, [1951])

Arnold Hauser

The tendency towards the monumental, the ceremonious and the solemn already disappears in the early rococo and makes room for a more delicate and intimate quality. In the new art preference is given to colour and shades of expression rather than to the great, firm, objective line and the note of sensuality and sentiment is to be heard in all its manifestations. (Social History of Art, 2005, [1951])

The Swing epitomizes this aesthetic shift. In the painting, the woman is set against a lush, unruly, and vast garden with streams of soft light illuminating the curling branches and intricate foliage. Like the lines we see in baroque paintings, the light surges diagonally from the top left of the canvas, immediately subverting the symmetrical composition of classicism. This way of depicting nature – how the light gently illuminates the fertile, ornate vegetation – creates a sense of mythological fantasy. This is heightened by the presence of cherubs below the woman and cupid above, symbolizing love and courtship. The whimsical romance of the piece is given a mischievous edge when we note that beneath the swinging woman is a man reclined in the foliage, looking directly up her billowing skirt. In the shadows to the left of the canvas, there’s an older man pulling on the ropes that propel the swing through the air.

This subject matter was scandalous for the time – The Swing creates the impression we are looking in on a secretive scene that even the painting’s subjects know is excessively lascivious – and that was exactly how the aristocracy wanted to be portrayed. The Swing was commissioned by a member of the royal court, and, like much rococo art, the painting was intended to be displayed in their private home. Prior to rococo, nobility was often associated with religion and education, depicted in acts of devotion or studious endeavors, but in rococo, it is pleasure and play that is at the forefront, just as the woman on the swing is shown in an act of sensual play. This better reflected the contemporary lives of nobility.

Stylistically, The Swing also embodied rococo. It is more painterly than baroque; visible, rapid brushstrokes give rococo paintings their energy and their ornamentation. In baroque, the paint is smoothed to create naturalistic gradients whereas in rococo, the oil paints layer and build-up. We can see examples of this in the bodice and ruffled hem of the young woman’s skirt. The use of pastel colors – pale pinks and muted greens and blues – were typical of rococo in all its decorative forms. It is these stylistic techniques, exemplified in Fragonard’s work, that gave the rococo such an unprecedented sense of mischievousness and indulgence.

Rococo and the feminine

Rococo is a movement often associated with femininity. Where baroque art was dark, dramatic and punishing – thought to be more masculine – rococo was light, fun and sensual. The use of pastel colors, the primacy of softness, and the subject of romance appeared to celebrate the feminine, appealing to the tastes, preferences and interests of women. Women were thought at the time to contribute significantly to those salon conversations about art, literature, and philosophy, as well as exercising notable influence in the aesthetic tastes of rococo. This much is alluded to in the autobiography of French painter, Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842). Commissioned to do portraits of a range of aristocrats, and being of high social standing herself, Vigée Le Brun spent her time immersed in the world of the ruling class. In her three-part autobiography titled Souvenirs of Madame Vigée Le Brun, one of the first memoirs of a female artist ever published, Vigée Le Brun looks back on the time of rococo, recounting, "Women reigned then, the Revolution dethroned them” (1835, [2023]).

Several historic symbols of femininity came out of the rococo period such as Madame de Pompadour (1721–1764) and Marie Antoinette (1755–1793). Marie Antoinette became a symbol for late rococo tastes. Having moved from Austria to France to marry King Louis XVI (1754–1793), she was styled so that she might better conform to the lavish fashions of the French nobility. She became known for her intricate and flirty rococo dress, with frills, ribbons, bows, and ruffles adorning her gowns alongside those of the other courtly women that surrounded her. She gained a reputation as the life of the party which was accompanied by copious rumors about her late-night escapades, drinking, and affairs. Much like the rococo movement itself, Marie Antoinette was accused of being shallow, frivolous, and completely out of touch with the struggles of 18th century France. In this way, she is a perfect symbol for the fun, expressive, and feminine nature of rococo as well as the movement’s more critical reception.

The end of rococo

Marie Antoinette’s life of luxury was abruptly ended via guillotine during the French Revolution, the same catalyst that facilitated the demise of the rococo movement as it was. While the aristocracy was reveling in the playful ornamentation of rococo, there was increasing unrest throughout France. On one hand, there was the intellectual insurrection of the Enlightenment that questioned the God-given power bestowed upon the ruling classes. The Enlightenment in France called for the radical disintegration of the Church and monarch and the destabilization of the aristocracy. Rococo, as an extension of the privileged classes, was heavily criticized at this time by enlightenment thinkers like M. de Voltaire (1694–1778) and Jacques-François Blondel (1705–1774) for its frivolity and elitism at a time of such crisis.

On the other hand, there was economic instability in France. Between the excessive spending of Louis XVI and France’s support in the American Revolution, the country was fast approaching bankruptcy. This served to further illustrate the vast inequality in France. Both these circumstances fostered anger at the privileges of nobility and called for a French constitution. It was these conditions that precipitated the French Revolution in 1789. As Lynn Hunt and Jack Censer summarize,

Armed with reason, the people had the right to demand a government that represented their interests, not those of the church, the aristocracy, or the monarch. (The French Revolution and Napoleon, 2017)

Lynn Hunt and Jack R. Censer

Armed with reason, the people had the right to demand a government that represented their interests, not those of the church, the aristocracy, or the monarch. (The French Revolution and Napoleon, 2017)

The revolution succeeded in undermining the power of the nobility. Stripped of their many privileges and forced to pay taxes, many aristocrats went into hiding and some were imprisoned and even killed. They were certainly no longer the central cultural power nor were they able to sit around indulging in their extravagant tastes, so rococo fell out of production and out of fashion. To capture the seriousness of the revolutionary cause, the imperial tastes of Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821), and the historic shifts taking place in France, the somber and austere neoclassicist movement took rococo’s place.

Rococo revival

Although rococo symbolized precisely what the French Revolution fought against, it wouldn’t be long until aspects of its unique aesthetic would return. In the early to mid-19th century, with the rise of the bourgeoisie, there was once more a demand for a light-hearted and opulent aesthetic. In Britain, this coincided with the rise of Romanticism and the fascination with landscape and nature. In furniture and décor, rococo motifs endured in Europe and the Americas, transcending the aristocratic symbol of frivolity, instead alluding to an organic and unencumbered artistic play.

What rococo captures is a particular moment in history, one where the imaginations of the aristocracy ran wild, leaving a lavish and whimsical aesthetic behind. It was a movement that changed the purpose and trajectory of art.

Today, rococo still symbolizes an escape from the tumult of modern life, featuring many important contemporary topics such as the environment, the expression of queerness, and the pursuit of pleasure.

Further reading on Perlego

Modes of Play in Eighteenth-Century France (2021) by Fayçal Falaky and Reginal McGinnis

Enlightened Animals in Eighteenth-Century Art (2021) by Sarah Cohen

Jean-Honoré Fragonard and Artworks (2023) by Edmond Goncourt and Jules Goncourt

Marie Antoinette’s Confidante (2016) by Geri Walton

François Blondel: Architecture, Erudition, and the Scientific Revolution (2012) by Anthony Gerbino

Rococo FAQs

What is rococo in simple terms?

What is rococo in simple terms?

What was the historic context of rococo?

What was the historic context of rococo?

What are the key characteristics of rococo art?

What are the key characteristics of rococo art?

What is an example of rococo art?

What is an example of rococo art?

Bibliography

Fragonard, J. H. and Russell, P. (2018) Delphi Complete Works of Jean-Honoré Fragonard. Delphi Classics Ltd. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1655932/delphi-complete-works-of-jeanhonor-fragonard-illustrated-pdf

Hauser, A. (2005) Social History of Art, Volume 3. 3rd edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1602255/social-history-of-art-volume-3-rococo-classicism-and-romanticism-pdf

Hunt, L. and Censer, J. (2017) The French Revolution and Napoleon. Bloomsbury Publishing. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/499877/the-french-revolution-and-napoleon-pdf

Silver, L. (2012) “Europe’s Golden Vision,” in Bohen, B., and Salow, J. (eds.) A Companion to Renaissance and Baroque Art. Wiley. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1004131/a-companion-to-renaissance-and-baroque-art-pdf

Vigée-Lebrun, L.-E. (2023) Souvenirs of Madame Vigée Le Brun. Patavium Publishing. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/4214237/souvenirs-of-madame-vige-le-brun-pdf

Walsh, L. (2016) A Guide to Eighteenth-Century Art. Wiley. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/990711/a-guide-to-eighteenthcentury-art-pdf

Artwork

Caravaggio, M. M. (1603) The Entombment of Christ [Oil on canvas]. Vatican Pinacoteca, Vatican City. (Uploaded on Wikimedia Commons; CC0 1.0)

Fragonard, J. H. (1766) The Swing [Oil on canvas]. The Wallace Collection, London. (Uploaded on Wikimedia Commons; CC0 1.0)

Watteau, J. A. (1717)The Embarkation for Cythera [oil on canvas] (uploaded by Sailko, Wikimedia Commons, 2013; CC BY 3.0)

PhD, Media Arts (Royal Holloway, University of London)

Aoiffe Walsh has a PhD in Media Arts from Royal Holloway, University of London. With a background in film studies and philosophy, her current research explores British literary modernism, with a particular focus on surrealism between the wars. She has lectured and published pieces on documentary and film theory, film history, genre studies and the avant-garde.