What is the Tragedy of the Commons?

MA, Management Science (University College London)

Date Published: 27.06.2023,

Last Updated: 19.07.2023

Share this article

Defining the Tragedy of the Commons

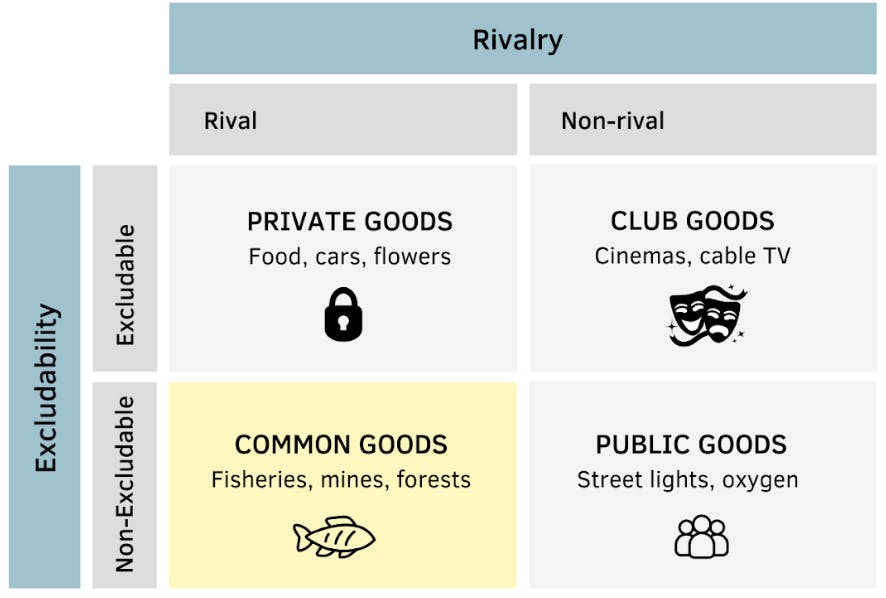

Goods are understood as products or services that individuals can purchase or sell. However, not all goods are the same. Economists like to classify goods depending on their degree of rivalry (i.e., if my consumption of the goods prevents your consumption of the goods) and excludability (i.e., if consumption is conditional on paying).

Common goods are rivalrous but non-excludable. This means that everyone is free to use them (non-excludable), but one person’s consumption of the goods will reduce the amount available to others (rivalrous). A useful example of a common goods is fish in the ocean. Everyone is free to go out and catch some fish, but the fish available in the sea will decrease every time. As explained in the book The Economics of Enough by Diane Coyle (2011), the Tragedy of the Commons argues that when consuming common goods, people will act in their self-interest and over consume them to the point of resource depletion.

Resources owned in common—such as fish in the ocean or clean air—are overused and therefore depleted. No individual owner takes responsibility for their stewardship, in the absence of any successful collective agreement to limit their depletion. The price we pay (essentially free) is lower than the price that would reflect the true cost of our use of them. This has distorted the development of advanced economies to make them far too hungry in their use of such resources.

Diane Coyle

Resources owned in common—such as fish in the ocean or clean air—are overused and therefore depleted. No individual owner takes responsibility for their stewardship, in the absence of any successful collective agreement to limit their depletion. The price we pay (essentially free) is lower than the price that would reflect the true cost of our use of them. This has distorted the development of advanced economies to make them far too hungry in their use of such resources.

It is considered a tragedy because consumers could avoid this phenomenon if they collaborated to maintain a sustainable consumption of common goods.

How was the Tragedy of Commons born?

The concept of the Tragedy of the Commons was first ideated in 1832 by the political economist at Oxford University, William Forster Lloyd. Like many economists of the time, including Malthus, Lloyd was fascinated by the effects of overpopulation and human behaviour on the economy. The book Stop, Thief! The Commons, Enclosures and Resistance (Peter Linebaugh, 2014) clearly explains how Lloyd was the first to question the effects of overpopulation on the commons. In Lloyd’s own words:

Why are the cattle on a common so puny and stunted? Why is the common itself so bare-worn and cropped so differently from the adjoining inclosures …? The common reasons for the establishment of private property in land are deduced from the necessity of offering individuals sufficient motives for cultivating the ground.

Peter Linebaugh

Why are the cattle on a common so puny and stunted? Why is the common itself so bare-worn and cropped so differently from the adjoining inclosures …? The common reasons for the establishment of private property in land are deduced from the necessity of offering individuals sufficient motives for cultivating the ground.

Indeed, Willam Forster Lloyd had observed that privately owned grazed meadows were green, healthy, and carried abundant grass throughout the year. However, neighbouring meadows that were publicly available to meadow men were lifeless and devastated. Why was this? This conundrum went unheard until economist Garrett Hardin published his famous paper ‘Tragedy of the Commons’ in 1968, where the phenomenon was given a name and made popular. In his paper, he further developed Lloyd’s findings. He described that if individuals had no incentive to behave charitably, they would act for their own benefit and exploit the available lands until depletion. Hardin references James Madison’s famous quote in the book The Federalist (James Madison, 1788).

"If men were angels, no Government would be necessary"

Alexander Hamilton & James Madison

"If men were angels, no Government would be necessary"

With privately owned lands, this was not the case. Indeed, landowners had the incentive to take care of their lands all year round to be able to generate sustained, long-term benefits from their cattle.

From Hardin’s contributions onwards, the Tragedy of the Commons has received a lot of attention, and many have attempted to refine and broaden the findings of the theory. For instance, the book The Tragedy of the Commodity (Stefano Longo, Rebecca Clausen, Brett Clark, 2015) takes a tangent on the traditional theory by analysing the phenomenon on specific biological commodity systems from a broader socio-economic lens:

This conceptualization offers analytical insight beyond the debates and discussions regarding common property resources or commons. [...] We expand on the broader sociological discussion that examines the historical, political, economic, and cultural forces shaping how we interact with the larger biophysical world.

What are some solutions to the Tragedy of the Commons?

In economics, this dynamic of the commons is often referred to as a market failure. Indeed, markets fail to manage commons and find mechanisms such that the unlimited desire to exploit these doesn’t compromise their existence in the future. Generally, governments are expected to fix market failures, and indeed, they often intervene to ensure the preservation of commons whilst upkeeping the economic health of nations.

Some well-known regulatory mechanisms are quotas or property rights. With quotas, governments may limit the number of fish you are allowed to catch every month. Failing to stick to the quota would result in a fine that no fisherman would want to incur. On the other hand, individuals can buy property rights from the government to own a portion of a common good (e.g., hectares of a field of land), transforming common-pool resources into privatised belongings. Individuals are incentivised to act as stewards and take care of the resource, thus preventing its overuse.

Elinor Ostrom, the first female Nobel Prize winner of Economic Sciences in 2009, was innovative in her thinking and approached the commons’ tragedy as a game theory puzzle. The book Democracy, Markets and the Commons by Lukas Peter (2021) explains how the Tragedy of the Commons can be looked at as a prisoner’s dilemma situation, where individuals are interrelated and can choose to collaborate to preserve the commons.

Elinor Ostrom approached the problem of democracy from a micro-situational perspective, drawing on game theory and focusing on social dilemmas and collective action. [...] In this sense, Ostrom understood the tragedy of the commons as a collective action or social dilemma, which, in turn, can also be understood as a prisoner's dilemma involving two people.

Lukas Peter

Elinor Ostrom approached the problem of democracy from a micro-situational perspective, drawing on game theory and focusing on social dilemmas and collective action. [...] In this sense, Ostrom understood the tragedy of the commons as a collective action or social dilemma, which, in turn, can also be understood as a prisoner's dilemma involving two people.

After applying game theory analysis to local communities that had successfully managed common resources, Elinor concluded that common-pool resources could be effectively managed by taking collective action, without government or private control. Elinor’s book Working Together (2010) explains some of her research and approach.

We examine several examples of collaboration, highlighting strategies developed to overcome practical constraints, and theoretical contributions to the study of collective action for natural resource management.

Amy R. Poteete, Marco A. Janssen & Elinor Ostrom

We examine several examples of collaboration, highlighting strategies developed to overcome practical constraints, and theoretical contributions to the study of collective action for natural resource management.

In practice, collective action takes the form of international agreements such as the Kyoto Protocol. Initiated by the United Nations, this agreement has been signed by 37 countries around the world to reduce greenhouse emissions in the atmosphere; the common-pool resource in this scenario.

What are some examples of the Tragedy of the Commons in real life?

Common goods are everywhere around us. As hinted in the section above, it is as simple as looking out the window or up to the sky to find one of the most at-risk elements to the tragedy of the commons: the atmosphere. Factories producing goods or farmers grazing their cattle are examples of parties that abusively use the atmosphere for their productive efforts. Indeed, the greenhouse gas and methane emissions produced by these respectively damage and deplete this valuable, shared resource. Agreements like the Kyoto or Montreal Protocols, or the objective of achieving Net Zero by 2050, are only some examples of collective action agreements that nations are taking to address this tragedy.

As explained in the book, Environmental Science for Dummies (Spooner, 2012), the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico is one of the fatal consequences of the Tragedy of the Commons. Countless farmers along the Mississippi River have used chemicals to grow their crops for centuries. These chemicals have been washed into the waters and killed the river’s biodiversity to the point where the Gulf of Mexico can no longer support any living creatures.

Each farmer has a right to treat his crops with fertilizers to boost production, but so many people use these chemicals that by the time the river empties into the Gulf, the chemical load is enough to disrupt the ecosystem. (Spooner, 2012)

Coffee consumption, traffic congestion, fast fashion or groundwater use are all good examples of the Tragedy of the Commons in real-life scenarios. Until now, it may seem that all common goods are natural resources. However, in later papers, Hardin explains that taxpayers’ money funds may also be considered a common good. He explains that in the savings and loans (S&L) crisis of the 1980s and 1990s, depositors (i.e., people keeping their money in banks) worried they would not get their money back. In response, the government set up the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC), which guaranteed depositor repayment using taxpayers’ money if banks broke. Thereon, taxpayers’ money became a common good that depositors exploited carelessly because they did not have to bear the cost behind using these funds. Eventually, the federal budget underwent significant losses and taxpayers commonly incurred the cost.

Closing thoughts

The Tragedy of the Commons proposes that individuals and collectives will over consume common-pool resources to the point of depletion and devastation. The atmosphere, rivers or fisheries are only some of the victims of the Tragedy of the Commons. Governments and economists have looked at this phenomenon from different angles, whether that was treating it as a market failure or a game theory puzzle. As a consequence of these different perspectives, different solutions have been generated to address and fix the tragedy. Governmental regulatory mechanisms (e.g., quotas and property rights) and collective agreements are only some of the most commonly used mechanisms which enable the more sustained consumption and preservation of the commons.

Further reading on Perlego

To read more about examples of the effects of the Tragedy of the Commons in economies and nations, read ‘Reinventing Collapse’ by Dmitry Orlov

To read more about the influence of population growth on the Tragedy of the Commons, read ‘Peak Everything: Waking Up to the Century of Declines’ by Richard Heinberg

To read about more real-life examples of the Tragedy of Commons, read ‘Economics for the Common’ by Jean Tirole, Steven Rendall

External resources on the Tragedy of the Commons

To read Garrett Hardin’s full paper, ‘Tragedy of the Commons’

To read more about Nobel Prize Winner Elinor Ostrom, ‘Elinor Ostrom’

To read more about the Savings and Loans Crisis, ‘Savings and Loans Crisis’

To read more about real-life collective agreements, ‘Net Zero Coalition’ and ‘Kyoto Protocol’

Bibliography

Hardin, G. (1968). The Tragedy of the Commons. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1724745

Coyle, D. (2011) The Economics of Enough. Princeton University Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/735093/the-economics-of-enough-how-to-run-the-economy-as-if-the-future-matters-pdf

Linebaugh, P. (2014) Stop, Thief! PM Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2584994/stop-thief-the-commons-enclosures-and-resistance-pdf

Hamilton, A. et al. (2005) The Federalist. Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3899109/the-federalist-pdf

Longo, S., Clausen, R. and Clark, B. (2015) The Tragedy of the Commodity. Rutgers University Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/400677/the-tragedy-of-the-commodity-pdf

Poteete, A., Janssen, M. and Ostrom, E. (2010) Working Together. Princeton University Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/734864/working-together-collective-action-the-commons-and-multiple-methods-in-practice-pdf

Poteete, A., Janssen, M. and Ostrom, E. (2010) Working Together. [edition unavailable]. Princeton University Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/734864/working-together-collective-action-the-commons-and-multiple-methods-in-practice-pdf

What is the Tragedy of the Commons in simple terms?

What is an example of the Tragedy of the Commons?

Who invented the idea of the Tragedy of the Commons?

MA, Management Science (University College London)

Inés Luque has a Masters degree in Management Science from University College London. During high school, she developed a strong interest in Economics, leading her to win the national Economics prize in her country of nationality, Spain. Her expertise is in the areas of microeconomics, game theory and design of incentives. Inés is passionate about the publishing industry and is currently working in the consulting department of the Financial Times in London.