What is Utility Theory?

MA, Management Science (University College London)

Date Published: 20.12.2023,

Last Updated: 16.07.2024

Share this article

Defining utility

Have you ever been in a situation where a friend, family member or acquaintance had a significantly different willingness to pay for a product than you did? This phenomenon happens because different people will obtain different levels of satisfaction or utility from consuming a product. Indeed, utility is the pleasure, benefit or satisfaction that humans get from acquiring a good or service.

Inevitably, the utility (or satisfaction) obtained from purchasing a good or service varies from person to person because not everyone is the same. For example, the happiness I get from acquiring a brand new bag or pair of shoes is likely to be very different from the utility you obtain. Essentially, not everybody has the same preferences, needs, interests, and values when going about their day-to-day lives. Economists have extensively studied this phenomenon, trying to find a single, generalizable theory that measures and explains why people extract different levels of utility or happiness from purchasing goods and services. The concept of utility is also important in moral philosophy (see our guide on utilitarianism), and it serves as the foundation of other elements of economic theory which continue to be relevant to this day (such as pricing mechanisms).

Different types of utility theory

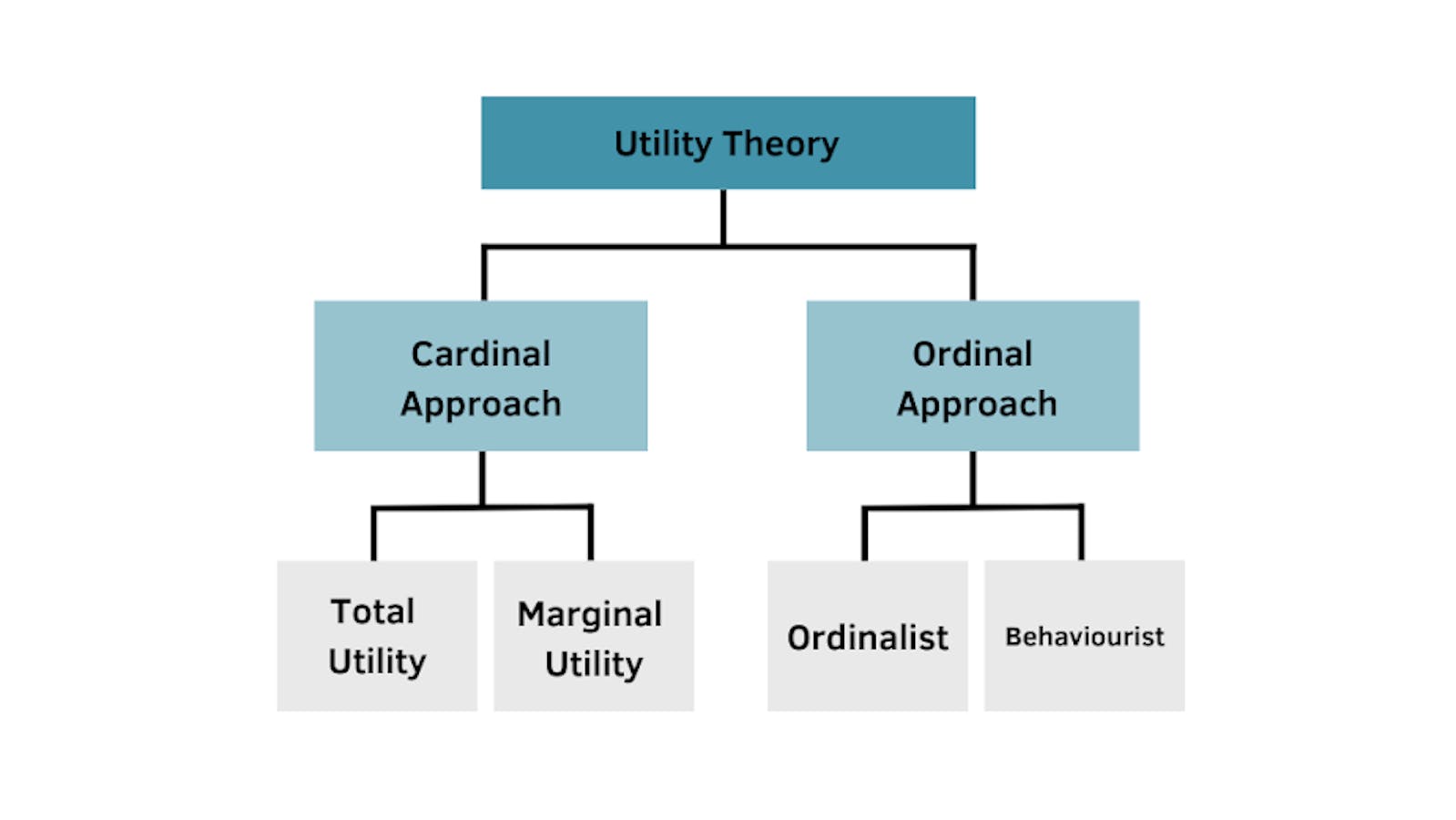

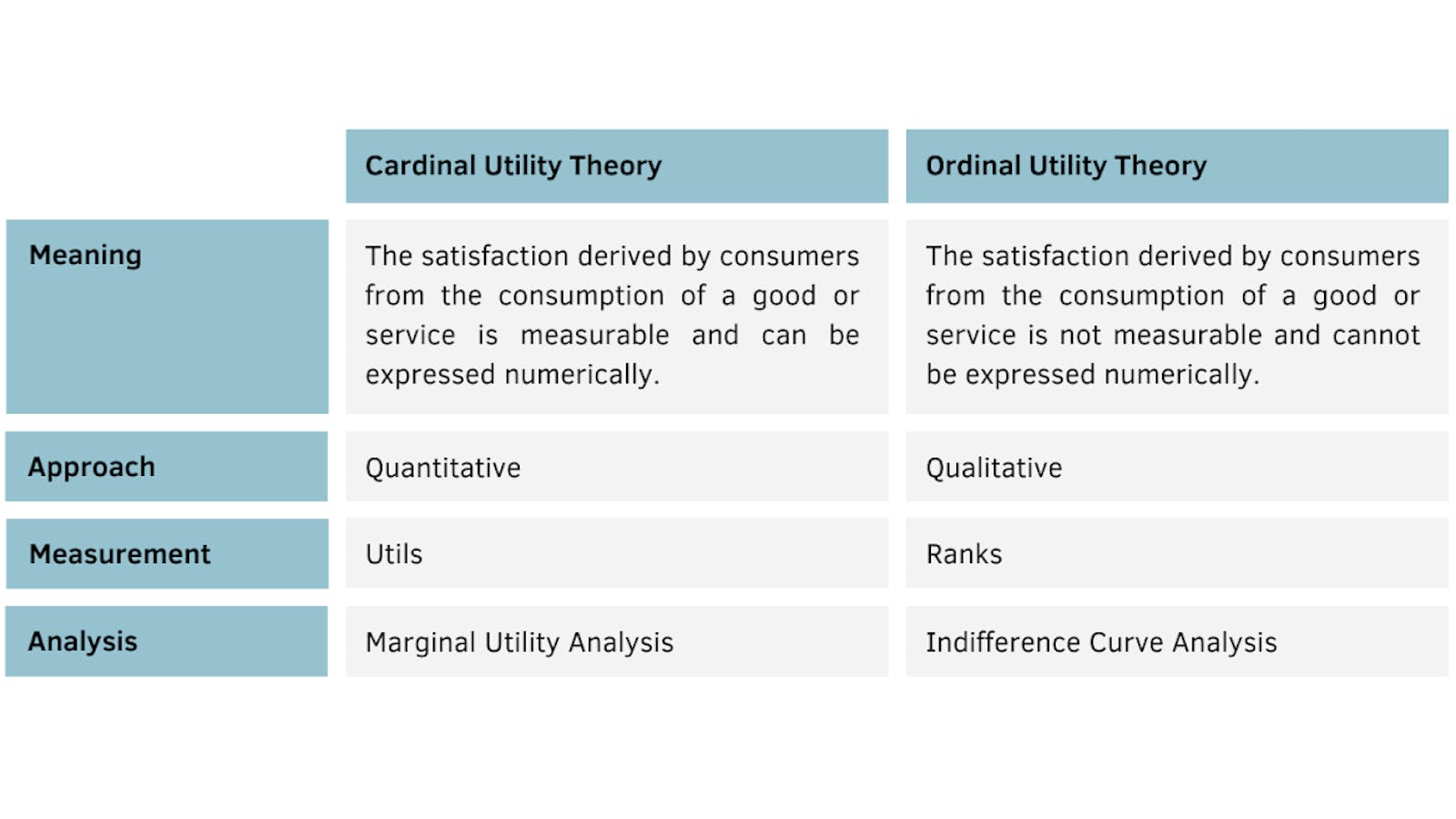

Throughout this study guide, one realizes that there is no wrong or right answer; there is no single valid utility theory that solves the conundrum. Essentially, there are two main approaches when it comes to thinking about utility: the cardinal and the ordinal utility approach. Broadly speaking, cardinal utility theory believes that this happiness or satisfaction when acquiring goods and services is measurable and quantifiable. Total utility and marginal utility are two different ways of measuring utility under this way of thinking (explored in the cardinal utility section below). On the other hand, ordinal utility theory holds that the utility one obtains from purchasing different goods and services cannot be measured, but only compared, ranked and ordered according to one’s preferences. Two different attitudes to ordinal utility theory emerged in the twentieth century: the ordinalist and the behaviorist. All of these various components of utility theory, then, can be seen in the table below.

Figure 1 — Breakdown of utility theory approaches and their components

Cardinal utility theory

Like many economic theories, conversations about utility really gathered momentum in the eighteenth century. Nicholas Bernoulli and Daniel Bernoulli, for example, explored the St. Petersburg paradox. Later, in 1776, Adam Smith famously explored the paradox of value in The Wealth of Nations. Smith questioned the heuristics and logic that individuals engage in when assigning a value to a good, and thereafter making consumption choices. He made a distinction between “value in use” and “value in exchange,” using water and diamonds as an analogy to explain his findings:

The word value, it is to be observed, has two different meanings, and sometimes expresses the utility of some particular object, and sometimes the power of purchasing other goods which the possession of that object conveys. The one may be called "value in use"; the other, "value in exchange." The things which have the greatest value in use have frequently little or no value in exchange; and, on the contrary, those which have the greatest value in exchange have frequently little or no value in use. Nothing is more useful than water: but it will purchase scarce anything; scarce anything can be had in exchange for it. A diamond, on the contrary, has scarce any value in use; but a very great quantity of other goods may frequently be had in exchange for it. (1776, [2021])

Adam Smith

The word value, it is to be observed, has two different meanings, and sometimes expresses the utility of some particular object, and sometimes the power of purchasing other goods which the possession of that object conveys. The one may be called "value in use"; the other, "value in exchange." The things which have the greatest value in use have frequently little or no value in exchange; and, on the contrary, those which have the greatest value in exchange have frequently little or no value in use. Nothing is more useful than water: but it will purchase scarce anything; scarce anything can be had in exchange for it. A diamond, on the contrary, has scarce any value in use; but a very great quantity of other goods may frequently be had in exchange for it. (1776, [2021])

Between the 1830s and 1840s, economists such as William Jevons and Léon Walras built upon this early thinking, and defined total utility and marginal utility as the measurable outputs of what they thought to be utility theory. Total utility is the total satisfaction that an individual receives from consuming a good or service. It is measured in “utils;” a hypothetical unit of measure for satisfaction. For example, one could say that the total utility of purchasing a new bag is 20 utils.

In the 1870s, Carl Menger, the Austrian economist and founder of the Austrian School of Economics, took total utility analysis one step further, and noted that utility should not be measured in total terms but in marginal terms. This means that one should not measure the total utility of consuming multiple units of a product, but instead, the change in utility from consuming an additional unit of that product. Indeed, Menger believed that utility was rather subjective and more complex than total utility accounted for. He believed that when attempting to measure utility, one should account for the fact that the value or satisfaction one gets from consuming a good will generally decrease as you consume more of it. In Principles of Economics (1871, [2007]), Menger writes:

The measure of value is entirely subjective in nature, and for this reason a good can have great value to one economizing individual, little value to another, and no value at all to a third, depending upon the differences in their requirements and available amounts. What one person disdains or values lightly is appreciated by another, and what one person abandons is often picked up by another. While one economizing individual esteems equally a given amount of one good and a greater amount of another good, we frequently observe just the opposite evaluations with another economizing individual.

In this way, Menger introduces the concept of the margin into subjective value theory. For more information, Max Alter’s Carl Menger And The Origins Of Austrian Economics (2019) is a useful resource.

Referring back to the bag example, the utility, satisfaction or happiness one obtains from purchasing their first ever bag is likely going to be greater than the utility obtained from repeatedly purchasing bags over time. Mathematically speaking, the difference between total and marginal utility is explained by Edgar K. Browning and Mark A. Zupan in Microeconomics (2019):

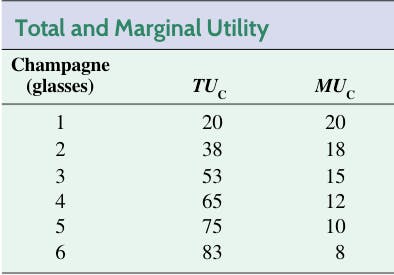

Total utility from champagne consumption (TUC) is the total utils Marilyn gets from a given number of glasses of champagne. If two glasses are consumed, total utility is 38 utils. Total utility is obviously greater at higher levels of consumption, because champagne is an economic good. The marginal utility of champagne (MUC) refers to the amount total utility rises when consumption increases by one unit. When champagne consumption increases from three to four glasses, total utility rises from 53 to 65 utils, or by 12 utils. The marginal utility of the fourth glass is thus 12 utils.

Edgar K. Browning and Mark A. Zupan

Total utility from champagne consumption (TUC) is the total utils Marilyn gets from a given number of glasses of champagne. If two glasses are consumed, total utility is 38 utils. Total utility is obviously greater at higher levels of consumption, because champagne is an economic good. The marginal utility of champagne (MUC) refers to the amount total utility rises when consumption increases by one unit. When champagne consumption increases from three to four glasses, total utility rises from 53 to 65 utils, or by 12 utils. The marginal utility of the fourth glass is thus 12 utils.

Image (cropped) taken from Table 3.2, Browning and Zupan, Microeconomics (2019)

Ordinal utility theory

In 1892, the American economist Irving Fisher published his groundbreaking book Mathematical Investigations in the Theory of Value and Prices, where he proposed an innovative approach to utility theory that contradicted the beliefs of cardinal utility theorists: ordinal utility. Indeed, he argued that economists should limit themselves to make assumptions on observable facts, and believed that attempting to measure utility (which he thought to be unobservable) was taking economic assumptions one step too far. As explained by Robert W. Dimand in Irving Fisher (2019), Fisher believed that utility theory belonged to the study of psychology and not economics, protesting that mixing these up was “inappropriate and vicious” (Fisher [1892], quoted by Dimand [2019]).

Instead, Fisher proposed that the only thing that could be inferred about utility from observing an individual’s behavior was whether the individual preferred product A over product B, or vice versa. He denoted his findings using utility functions, exemplified below.

- U(A) > U(B) => Individual prefers A to B

- U(A) < U(B) => Individual prefers B to A

- U(A) = U(B) => Individual is indifferent between A and B

In the late 1800s, the renowned English philosopher and political economist Francis Ysidro Edgeworth developed Fisher’s findings, extrapolating his analysis to situations where there are more than two products and more than one individual expressing their preferences in the economy. Edgeworth graphically mapped his analysis as “indifference curves,” which are explained here by Thomas J. Nechyba:

Consider a two-dimensional map of a mountain, a map in which different heights of the mountain are represented by outlines of the shape of the mountain at that height accompanied by a number that indicates the elevation of that outline. In essence, such maps are depictions of horizontal slices of the mountain at different heights drawn on a single two-dimensional surface. Indifference curves are very much like this. Longitude and latitude are replaced with jeans and hoodies, and the height of the mountain is replaced with the level of happiness. While real world mountains have peaks, our happiness mountains generally do not have peaks because of our more is better assumption. (2018)

Thomas J. Nechyba

Consider a two-dimensional map of a mountain, a map in which different heights of the mountain are represented by outlines of the shape of the mountain at that height accompanied by a number that indicates the elevation of that outline. In essence, such maps are depictions of horizontal slices of the mountain at different heights drawn on a single two-dimensional surface. Indifference curves are very much like this. Longitude and latitude are replaced with jeans and hoodies, and the height of the mountain is replaced with the level of happiness. While real world mountains have peaks, our happiness mountains generally do not have peaks because of our more is better assumption. (2018)

One could say that Fisher and Edgeworth’s approach to utility theory was an ordinal ordinalist approach (refer to Figure 1). So what does a behaviorist approach to ordinal utility theory look like? Notice that, even though the ordinal approach to utility theory is less quantitative than cardinal utility theory, there is still some kind of mathematical intent in its analysis with the use of utility functions and indifference curves. The behaviorist approach, on the other hand, completely abandons the idea of explaining utility using mathematical notation, and argues that what we can tell from utility is entirely from observed human behavior. This approach was introduced by Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto in his article “Summary of Some Chapters of a New Treatise on Pure Economics” (1900, [2008]). Pareto caused a turning point in the study of utility theory with his behaviorist approach, and also made significant contributions to the ordinalist approach (with the concept known as Pareto efficiency, for example).

Closing thoughts

To conclude, utility theory studies the logic behind people obtaining different levels of satisfaction from the consumption of goods and services. Because happiness and satisfaction are rather subjective and abstract concepts, it is difficult to explain utility theory without approaching it from a philosophical perspective, and diving into the different historical milestones that have shaped this theory over time. Indeed, throughout the guide we have explored how the interest for utility theory first arose with the classical economics of Adam Smith. Economists including William Jevons and Carl Menger built upon the intellectual seed that Smith had planted, and developed utility theory following a cardinal approach where total and marginal utility are measurable and expressed in “utils.” Irving Fisher was combative in his thinking and approached utility theory with a more psychological and arguably modest perspective, stating that utility is not measurable but rankable. Other economists, like Pareto, took a more extreme stand on utility theory by completely rejecting the use of mathematical modeling to explain such an abstract phenomenon. The key components for each of the approaches to utility theory are summarized in Table 1 below. It is important to note that there is no wrong or right answer to such a conundrum, and that it is all a matter of perspective.

Table 1 — Summary of the differences between cardinal and ordinal utility theory

Further reading on Perlego

To read more about utility theory and its evolution through history, you can read Happiness and Utility (2019), edited by by Georgios Varouxakis and Mark Philp

To read more about utility theory in the context of political theory, you can read The Tyranny of Utility: Behavioural Science and the Rise of Paternalism (2011) by Gilles Saint-Paul

To find out more about the history of marginal utility theory, you can read History of Marginal Utility Theory (2015) by Emil Kauder

To read more about utility theory in our day-to-day lives, you can read Economics as an Evolutionary Science: From Utility to Fitness (2018) by Arthur E. Gandolfi, Anna Sachko Gandolfi, and David P. Barash

Utility theory FAQs

What is utility theory in simple terms?

What is utility theory in simple terms?

What is the difference between cardinal and ordinal utility?

What is the difference between cardinal and ordinal utility?

What is the difference between total and marginal utility?

What is the difference between total and marginal utility?

Bibliography

Alter, M. (2019) Carl Menger And The Origins Of Austrian Economics. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1501667/carl-menger-and-the-origins-of-austrian-economics-pdf

Browning, E. and Zupan, M. (2019) Microeconomics. 13th edn. Wiley. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3866183/microeconomics-theory-and-applications-pdf

Dimand, R. (2019) Irving Fisher. Springer International Publishing. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3494708/irving-fisher-pdf

Fisher, I. (1891). Mathematical Investigations in the Theory of Value and Prices. Harvard University Graduate School of Business Administration. Available at: https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/books/mathematical_fisher.pdf

Peterson, M. "The St. Petersburg Paradox," The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Fall 2023 Edition. Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2023/entries/paradox-stpetersburg/

Menger, C. (2007) Principles of Economics. The Ludwig von Mises Institute. Available at: https://mises.org/library/principles-economics

Moscati, I. (2019) Measuring Utility: From the Marginal Revolution to Behavioral Economics. Oxford University Press.

Nechyba, T. (2018) Intermediate Microeconomics: An Intuitive Approach with Calculus. Cengage Learning EMEA. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2754492/intermediate-microeconomics-an-intuitive-approach-with-calculus-pdf

Pareto, V. (2008). Summary of Some Chapters of a New Treatise on Pure Economics. Giornale Degli Economisti e Annali Di Economia, 67 (Anno 121) (3), 453–504. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23248332

Smith, A. (2021) Wealth of Nations. Icarsus. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2628240/wealth-of-nations-pdf

MA, Management Science (University College London)

Inés Luque has a Masters degree in Management Science from University College London. During high school, she developed a strong interest in Economics, leading her to win the national Economics prize in her country of nationality, Spain. Her expertise is in the areas of microeconomics, game theory and design of incentives. Inés is passionate about the publishing industry and is currently working in the consulting department of the Financial Times in London.