What is the Multiplier Effect?

MA, Management Science (University College London)

Date Published: 17.08.2023,

Last Updated: 14.09.2023

Share this article

Defining the multiplier effect

Think of a ripple. Ripples in the water are initiated by a movement or action (e.g., the throw of a pebble) that causes subsequent water rings to spread and multiply. This is an analogy for the multiplier effect. In economics, the multiplier effect happens when the change in a particular economic input (e.g. government spending) causes a larger change in an economic output (e.g. gross domestic product).

The multiplier effect was first theorized by economist Paul Samuelson in his paper “The Relation of Home Investment to Unemployment” (1931). John Maynard Keynes, the founder of Keynesian economics, further developed and applied Samuelson’s idea in his book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936, [2021]).

The conception of the multiplier was first introduced into economic theory by R. F. Kahn in his article on 'The Relation of Home Investment to Unemployment' (Economic Journal, June 1931).

From there onwards, it has been used as a theoretical and mathematical concept to understand how economies evolve and develop. The book Narrative Economics (Shiller, 2020) describes the chain reasoning behind the workings of the multiplier effect in general terms:

According to Keynesian theory, an economic boom starts when some initial stimulus, such as government deficit spending, causes an initial increase in some people's income. These people then spend much of their additional income, which in turn generates income for other people who sell to them or work for companies that sell to them. They in turn spend much of this extra income, thus generating another round of income increases for yet other people, and so on in multiple rounds of expenditure.

Robert J. Shiller

According to Keynesian theory, an economic boom starts when some initial stimulus, such as government deficit spending, causes an initial increase in some people's income. These people then spend much of their additional income, which in turn generates income for other people who sell to them or work for companies that sell to them. They in turn spend much of this extra income, thus generating another round of income increases for yet other people, and so on in multiple rounds of expenditure.

It is important to note that the multiplier effect can go both ways. That is, the ripple effect can be positive whereby a change in an input leads to a larger and positive change in an economic output. However, it may also be the case that:

According to the Keynes-Kahn multiplier, one bad work generates two bad works, a divergent series that sums to minus infinity. (Paul Samuelson, quoted by Donald A. Walker in Paul Samuelson: Master of Modern Economics, 2020)

Edited by Robert A. Cord, Richard G. Anderson and William A. Barnett

According to the Keynes-Kahn multiplier, one bad work generates two bad works, a divergent series that sums to minus infinity. (Paul Samuelson, quoted by Donald A. Walker in Paul Samuelson: Master of Modern Economics, 2020)

How is the multiplier effect applied?

The multiplier effect can be used by anyone, whether that is governments, organizations or working individuals. Generally, these different entities and people will apply multiplier effect theory to quantify the effects of a given action (such as additional or decreased spending)….

For governments, the scale and magnitude of these variables (i.e., spending and income) is nationwide. That is, they look at the effect of government spending on total aggregate income (also known as output or GDP) in an economy. Individuals will likely apply the multiplier effect on a smaller scale, looking at the effect that an investment in, say, their education, can have on their future annual income. Equally, organizations will look at the effect that spending on machinery can have on revenue or profits. Regardless of who is applying the theory, the general formula to calculating the multiplier effect is as follows:

Multiplier Effect = Change in Income / Change in Spending

For example, say that the UK government spends £1 million in improving and renewing the infrastructure for public transport in London. Commuters in London appreciate these changes and increasingly use and spend more on public transport. The government notices that the increase in spending is £5 million from the time of their investment. Here, the injected income in the economy is £1 million, and spending has increased by £5 million. Therefore, the multiplier effect is 5 (£5 million / £1 million). This means that every £1 of government spending on public transport increased spending by £5.

More and more, people are noticing the versatility of applying the multiplier effect in real life. For example, the book Multipliers: How the Best Leaders Make Everyone Smarter (Wiseman, 2017) goes beyond the economic and numerical meaning of the Multiplier Effect exemplified above, and defines “multipliers” to be people that contagiously and naturally empower those around them to be the best version of themselves, creating thus a multiplier effect:

Multipliers are genius makers. What we mean by that is that they make everyone around them smarter and more capable. Multipliers invoke each person's unique intelligence and create an atmosphere of genius innovation, productive effort, and collective intelligence.

Liz Wiseman

Multipliers are genius makers. What we mean by that is that they make everyone around them smarter and more capable. Multipliers invoke each person's unique intelligence and create an atmosphere of genius innovation, productive effort, and collective intelligence.

What types of multiplier effect exist?

The multiplier effect is mainly used in macroeconomics to understand the effect that changing one variable in an economy has on another variable. For example, the fiscal multiplier, also known as the Keynes-Kahn multiplier was the first one to emerge and is the most well-known type of multiplier effect. As explained in the book A Concise Guide to Macroeconomics (Moss, 2014), it looks at the effect of changing government spending on gross domestic product (or national income) in an economy.

Keynes himself described the mechanism in terms of an income multiplier. Because he believed that a burst of deficit spending by the government would lead both consumption and investment to rise, Keynes concluded that national income (or GDP) would increase by more than the original increase in government spending.

David A. Moss

Keynes himself described the mechanism in terms of an income multiplier. Because he believed that a burst of deficit spending by the government would lead both consumption and investment to rise, Keynes concluded that national income (or GDP) would increase by more than the original increase in government spending.

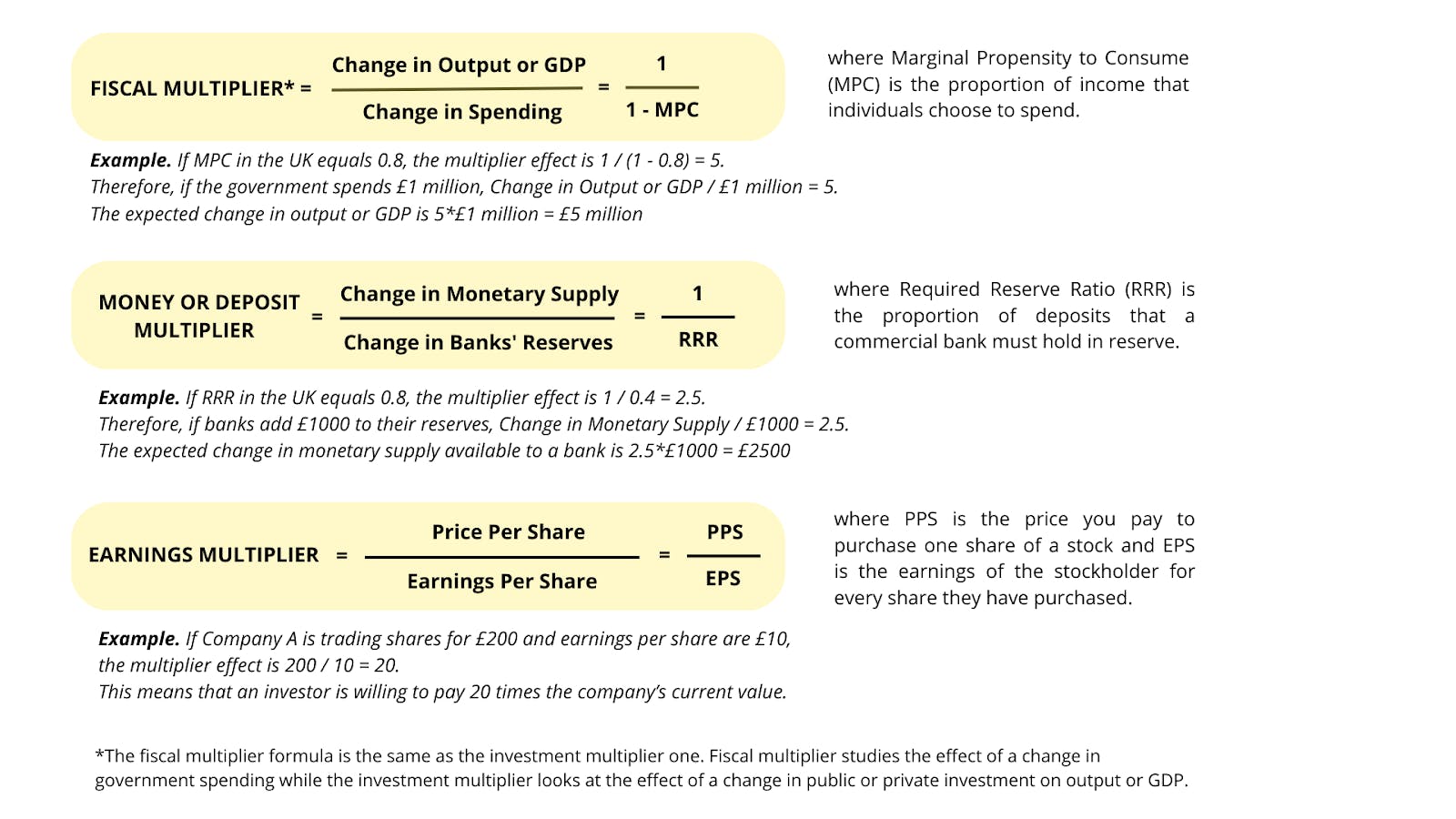

Because there are many alterable variables in an economy, there are several types of multiplier effects. This article covers five of the most commonly used multiplier effects in day-to-day economics: fiscal, money or deposit, investment and earnings multipliers. A small calculation is conducted to measure the strength of each of these multiplier effects. The formulae and examples for each of the multipliers are shown in Figure 1.

- Fiscal multiplier. The effect of a change in government spending or taxes on gross domestic product (or national income). It is also known as the Keynesian-Kahn multiplier.

- Money or deposit multiplier. The effect of a change in banks’ monetary reserves (i.e., currency that is set aside or saved by banks for future use) on the amount of monetary supply available in a bank.

- Investment multiplier. The effect of a change in public or private investment (e.g., R&D by organizations) on gross domestic product (or national income).

- Earnings multiplier. The effect of a change in the price of a stock on stockholders' per-share earnings.

The reason why these ratios are all called “multipliers” is because an initial economic input amplifies or “multiplies” the effect of some other variable.

Figure 1 - Formulas and Examples for Different Types of Multipliers

What are the limitations and criticisms of the multiplier effect?

When translating economic theory to real life, the numbers don’t always add up. As a matter of fact, like every economic theory, the multiplier effect also contains some limitations. One of the most significant criticisms of the multiplier effect was expressed by the famous economics and business journalist, Henry Hazlitt. In his book The Failure of the "New Economics": An Analysis of the Keynesian Fallacies (1959, [2016]), he was vocal on his belief that the multiplier effect was “too good to be true”;

Their multiplier is too good to be true. [...] Keynes’ multiplier is a myth. There is never any fixed, predictable multiplier; there is never any precise, predeterminable, or mechanical relationship between social income, consumption, investment, and extent of employment.

Henry Hazlitt

Their multiplier is too good to be true. [...] Keynes’ multiplier is a myth. There is never any fixed, predictable multiplier; there is never any precise, predeterminable, or mechanical relationship between social income, consumption, investment, and extent of employment.

Other economists were convinced by the overarching idea of the multiplier effect, but acknowledged some limitations regarding its validity when applied to real life situations. Indeed, in his paper "Mr. Keynes' Theory of the 'Multiplier': A Methodological Criticism" (1936), the Austrian-American economist and Harvard professor Gottfried Haberler argued that there was insufficient empirical evidence that the multiplier effect worked in real life:

Keynes offers no adequate proof, only a number of rather disconnected observations.

Similarly, the renowned Nobel Prize Laureate Milton Friedman pointed out that the multiplier effect was flawed, arguing that the theory only held if other economic dynamics were ignored at the happening of this effect. Indeed, in his book Capitalism and Freedom (1962, [2009]), he numerically proves that if other economic elements are taken into account when calculating the multiplier effect, the latter crumbles.

This simple analysis is extremely appealing [referring to Keynes’ multiplier effect theory]. But the appeal is spurious and arises from neglecting other relevant effects of the change in question. When these are taken into account, the final result is much more dubious: it may be anything from no change in income at all, in which case private expenditures will go down by the $100 by which government expenditures go up, to the full increase specified. And even if money income increases, prices may rise, so real income will increase less or not at all.

Milton Friedman

This simple analysis is extremely appealing [referring to Keynes’ multiplier effect theory]. But the appeal is spurious and arises from neglecting other relevant effects of the change in question. When these are taken into account, the final result is much more dubious: it may be anything from no change in income at all, in which case private expenditures will go down by the $100 by which government expenditures go up, to the full increase specified. And even if money income increases, prices may rise, so real income will increase less or not at all.

Closing thoughts

To conclude, the multiplier effect is a theory that emerges from Keynesian economics. It happens when the change in a particular economic input causes a larger change in an economic output. It is like a ripple effect; a chain reaction. In the real world, people (e.g., governments, organizations, or working individuals) will generally use the multiplier effect to understand the amplifying potential that their investments and spending can have on their life. While the multiplier effect can go both ways (either positively or negatively), it is commonly used optimistically to understand how one’s actions may lead to magnified and multiplied returns as opposed to diminished.

Further reading on Perlego

To read more about “multipliers”, read The Prosperity Paradox: How Innovation Can Lift Nations Out of Poverty by Clayton M. Christensen, Efosa Ojomo, Karen Dillon

To read more of journalists Hazlitt’s work, read Thinking as a Science by Henry Hazlitt

To read more about Paul Samuelson’s work and development of the multiplier effect, read Paul Samuelson and the Foundations of Modern Economics by K. Puttaswamaiah

To read more about how economic concepts can be applied in the real world, read The Little Book of Economic: How the Economy Works in the Real World by Greg Ip

Multiplier effect FAQs

What is the multiplier effect in simple terms?

What is the multiplier effect in simple terms?

What is the formula for the multiplier effect?

What is the formula for the multiplier effect?

Why is the multiplier effect important?

Why is the multiplier effect important?

Bibliography

Cord, R., Anderson, R. and Barnett, W. (2020) Paul Samuelson: Master of Modern Economics. Palgrave Macmillan UK. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3480283/paul-samuelson-master-of-modern-economics-pdf

Friedman, M. (2009) Capitalism and Freedom. The University of Chicago Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1853344/capitalism-and-freedom-fortieth-anniversary-edition-pdf

Hazlitt, H. (2016) The Failure of the ‘New Economics’: An Analysis of the Keynesian Fallacies. Golden Springs Publishing. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3019149/the-failure-of-the-new-economics-an-analysis-of-the-keynesian-fallacies-pdf

Keynes, J. M. (2021) The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. Strelbytskyy Multimedia Publishing. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3042299/the-general-theory-of-employment-interest-and-money-illustrated-pdf

Moss, D. (2014) A Concise Guide to Macroeconomics. Harvard Business Review Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/837335/a-concise-guide-to-macroeconomics-second-edition-what-managers-executives-and-students-need-to-know-pdf

Shiller, R. (2020) Narrative Economics. Princeton University Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1440241/narrative-economics-how-stories-go-viral-and-drive-major-economic-events-pdf

Wiseman, L. (2017) Multipliers, Revised and Updated. HarperCollins. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/588995/multipliers-revised-and-updated-pdf

External sources on the multiplier effect

To find out more about the origins of the multiplier effect, read The Relation of Home Investment to Unemployment by Paul Samuelson.

To read more about Haberler's criticisms of the multiplier effect, read “Mr. Keynes' Theory of the ‘Multiplier’: A Methodological Criticism” by Gottfried Haberler.

MA, Management Science (University College London)

Inés Luque has a Masters degree in Management Science from University College London. During high school, she developed a strong interest in Economics, leading her to win the national Economics prize in her country of nationality, Spain. Her expertise is in the areas of microeconomics, game theory and design of incentives. Inés is passionate about the publishing industry and is currently working in the consulting department of the Financial Times in London.