eBook - ePub

The Darker Side of Travel

The Theory and Practice of Dark Tourism

- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Darker Side of Travel

The Theory and Practice of Dark Tourism

About this book

Over the last decade, the concept of dark tourism has attracted growing academic interest and media attention. Nevertheless, perspectives on and understanding of dark tourism remain varied and theoretically fragile whilst, to date, no single book has attempted to draw together the conceptual themes and debates surrounding dark tourism, to explore it within wider disciplinary contexts and to establish a more informed relationship between the theory and practice of dark tourism. This book meets the undoubted need for such a volume by providing a contemporary and comprehensive analysis of dark tourism.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Darker Side of Travel by Richard Sharpley, Philip R. Stone, Richard Sharpley,Philip R. Stone in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Hospitality, Travel & Tourism Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Dark Tourism: Theories and Concepts

Chapter 1

Shedding Light on Dark Tourism: An Introduction

Introduction

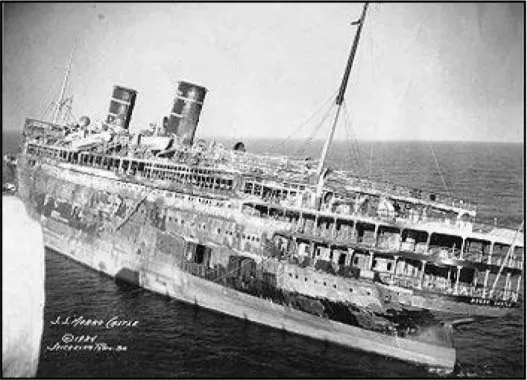

On 23 August 1930, the SS Morro Castle, named after the fortress that guards the entrance to Havana Bay, set out on her maiden voyage from New York City to Cuba. Offering luxurious, though affordable, travel as well as a Prohibition-era opportunity for the legal consumption of alcohol, the ship immediately became popular among tourists and business travellers alike and over the next four years successfully plied the route between the New York and Havana.

In the early hours of 8 September 1934, however, disaster struck. During the previous evening, as the ship was approaching the eastern seaboard of the USA on the return journey from Havana, Captain Robert Wilmott apparently suffered a heart attack and died in his bathtub and, as a consequence, command passed to the First Officer, William Warms. At 2.45 am, fire broke out in the First Class Writing Room and quickly spread, with design faults and questionable crew practices contributing to the conflagration. For a variety of reasons, including alleged indecision on the part of the captain, the SOS was not sent out until 3.25 am, by which time the ship had lost all power and was fully ablaze. Despite the ship's position close to the shore, rescue operations were slow and ineffective and the eventual death toll amounted to 137 passengers and crew out of a total of 549 people on board (Gallagher, 2003; Hicks, 2006).

The devastating fire on the SS Morro Castle remains one of America's worst and most controversial peacetime maritime disasters and at the time led to significant fire safety improvements in ship design. However, it was also notable for the fact that large numbers of people arrived to witness the aftermath of the event. Attempts to salvage the ship were unsuccessful and, driven by the wind, the smouldering wreck, with numerous victims still aboard, drifted onto the shore of New Jersey at Asbury Park (Figure 1.1). Almost immediately it became a tourist attraction. Spurred on by newspaper and radio reports and special excursion train fares from New York and Philadelphia (Hegeman, 2000), up to a quarter of a million people travelled to view the wreck and, according to press reports at the time, almost a carnival atmosphere prevailed. As Hegeman (2000) observes, ‘the scene at the wreck of the Morro Castle was both a spontaneous public festival and a media event. Postcards were printed, souvenirs were sold, and radio broadcasts offered … firsthand accounts of the scene on board the wreck complete with lurid descriptions of charred corpses.’ It was even proposed that the wreck should be permanently moored at Asbury Park as a tourist attraction, although it was eventually towed away to be sold for scrap some six months later.

Figure 1.1 The wreck of the SS Morro Castle

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Morro_Castle (GNU Free Document License)

In short, the SS Morro Castle disaster was an early, while by no means the first, example of a phenomenon that has more recently come to be referred to as ‘dark tourism’. Indeed, for as long as people have been able to travel, they have been drawn – purposefully or otherwise – towards sites, attractions or events that are linked in one way or another with death, suffering, violence or disaster (Stone, 2005a; Seaton, forthcoming). For example, the gladiatorial games of the Roman era, pilgrimages, and attendance at medieval public executions were early forms of such death-related tourism. Boorstin (1964) alleges that the first guided tour in England in 1838 was a trip by train to witness the hanging of two murderers. In the specific context of warfare, Seaton (1999) observes that death, suffering and tourism have been related for centuries (see also Smith, 1998; Knox, 2006), citing visits to the battlefield of Waterloo from 1816 onwards as a notable 19th-century example of what he terms ‘thanatourism’. Also in the 19th century, visits to the morgue were, as MacCannell (1989) notes, a regular feature of tours of Paris – perhaps a forerunner of the ‘Body Worlds’ exhibitions in London, Tokyo and elsewhere that have attracted visitors in their tens of thousands since the late 1990s (www.bodyworlds.com/en.html).

As will be considered shortly, the extent to which dark tourism may be considered a historical phenomenon – that is, visiting sites or attractions that predate living memory – remains a subject of debate (Wight, 2006). It is clear, however, that visitors have long been attracted to places or events associated in one way or another with death, disaster and suffering. Equally, there can be little doubt that, over the last half century and commensurate with the remarkable growth in general tourism, dark tourism has become both widespread and diverse. In terms of supply, there has been a rapid growth in the provision of such attractions or experiences; indeed, there appears to be an increasing number of people keen to promote or profit from ‘dark’ events as tourist attractions, such as the Pennsylvania farmer who offered a $65 per person ‘Flight 93 Tour’ to the crash site of the United Airlines Flight 93 – one of the 9/11 aircraft (Bly, 2003). Moreover, dark tourism has become more widely recognised both as a form of tourism and as a promotional tool, with websites such as www.thecabinet.com listing numerous dark tourism sites around the world (Dark Destinations, 2007).

At the same time, there is evidence of a greater willingness or desire on the part of tourists to visit dark attractions and, in particular, the sites of dark events. For example, in August 2002 local residents in the small town of Soham in Cambridgeshire, UK appealed for an end to the so-called ‘grief tourism’ that was bringing tens of thousands of visitors to their town. Many of these visitors, travelling from all over Britain, had come to lay flowers, light candles in the local church or sign books of condolence. Others had simply come to gaze at the town – indeed, it was reported that tourist buses en route to Cambridge or nearby Ely Cathedral were making detours through the town (O'Neill, 2002). They had been drawn to Soham by its association with a terrible – and highly publicised – crime: the abduction and murder of two young schoolgirls. In the same year, Ground Zero in New York attracted three-and-a-half million visitors, almost double the number that annually visited the observation platform of the World Trade Center prior to 9/11 (Blair, 2002). Interestingly, echoing what had occurred at Asbury Park almost 70 years earlier, the site also attracted numerous street vendors ‘selling trinkets that run the gamut of taste’ (Vega, 2002); souvenirs on sale ranged from framed photographs of the burning towers to Osama Bin Laden toilet paper, his picture printed on each square (see also Lisle, 2004). More generally, evidence suggests that contemporary tourists are increasingly travelling to destinations associated with death and suffering. According to one recent report, for example, places such as Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Angola and Afghanistan are experiencing a significant upsurge in tourism demand (Rowe, 2007).

Nevertheless, despite the long history and increasing contemporary evidence of travel to sites or attractions associated with death, it is only relatively and, perhaps, surprisingly recently that academic attention has been focused upon what has collectively been referred to as ‘dark tourism’ (Foley & Lennon, 1996a). More specifically, the publication of Lennon and Foley's (2000) Dark Tourism: The Attraction of Death and Disaster introduced the term to a wider audience, stimulating a significant degree of academic interest and debate. It is interesting to note, for example, that the dark tourism academic website (www.dark-tourism.org.uk), established by one of the authors of this book, annually receives over 60,000 hits. At the same time, media interest in the concept of dark tourism continues to grow, the juxtaposition of the words ‘dark’ and ‘tourism’ undoubtedly providing an attention-grabbing headline. However, to date, the academic literature remains eclectic and theoretically fragile and, consequently, understanding of the phenomenon of dark tourism remains limited. Certainly, numerous attempts have been made to define or label death-related tourist activity, with many commentators exploring and analysing specific manifestations of dark tourism, from war museums which adopt both traditional and contemporary museology methods of (re) presentation (Wight & Lennon, 2004) to genocide commemoration visitor sites and the political ideology attached to such remembrance (Williams, 2004). Much of the literature tends to be descriptive and ‘supply-side comment and analysis’ (Seaton & Lennon, 2004; Stone, 2005b); conversely, a demand-side perspective has been notably lacking for the most part, although some recent work has begun to focus on demand-related issues (Preece & Price, 2005; Yuill, 2003).

As a result, a number of fundamental questions with respect to dark tourism remain unanswered, not least whether it is actually possible or justifiable to categorise collectively the experience of sites or attractions that are associated with death or suffering as ‘dark tourism’. That is, such is the variety of sites, attractions and experiences now falling under the collective umbrella of dark tourism that the meaning of the term has become increasingly diluted and fuzzy. More specifically, it remains unclear whether dark tourism is tourist-demand or attraction-supply driven or, more generally, the manifestation of what has been referred to as a (post) modern propensity for ‘mourning sickness’ (West, 2004). Other questions are also raised, but go unanswered in the literature. For example, has there indeed been a measurable growth in ‘tourist interest in recent death, disaster and atrocity … in the late 20th and early 21st centuries’ (Lennon & Foley, 2000: 3) or is there simply an ever-increasing supply of ‘dark’ sites and attractions? Are there degrees or ‘shades’ of darkness that can be related to either the nature of the attraction or the intensity of interest in death or the macabre on the part of tourists (Miles, 2002; Strange & Kempa, 2003; Stone, 2006a)? What management or ethical issues are raised by labelling sites or attractions as ‘dark’? And, does the popularity of ‘dark’ sites result from a basic, voyeuristic interest or fascination with death, or are there more powerful motivating factors?

The overall purpose of this book is to address these and other questions, thereby advancing knowledge and understanding of the phenomenon of dark tourism. In other words, it sets out to provide a contemporary and comprehensive analysis of dark tourism that, drawing upon extant concepts and introducing new theoretical perspectives on the subject, develops a theoretically informed foundation for examining the demand for and supply of dark tourism experiences. In particular, it identifies and explores issues relevant to the development, management and interpretation of dark sites and attractions, focusing in particular on the relationship between dark tourism and the cultural condition and social institutions of contemporary societies. The first task, however, is to establish the context of the book through a review of contemporary perspectives on dark tourism. The purpose of this introductory chapter is to set the scene for the concepts, debates and challenges considered in subsequent chapters.

But Why Study Dark Tourism?

To some extent, the increasing attention paid to the phenomenon of dark tourism in recent years may arguably be symptomatic of the trend within academic circles to identify and label specific forms of tourism, or to subdivide tourism into niche products and markets (Novelli, 2005). That is, the study of dark tourism may be considered simply as an academic endeavour. Equally, it may be seen as a specific manifestation of a wider social interest or fascination in death. As suggested earlier, a combination of the words ‘dark’ or ‘grief’ with ‘tourism’, the latter connoting relaxation, escape, hedonism or pleasure, creates an enticing headline. Thus, dark tourism may also be considered an example of media hype responding to this presumed fascination in death and dying.

However, the study of dark tourism is both justifiable and important for a number of reasons. Generally, as the following section reveals, dark tourism sites and attractions are not only numerous but also vary enormously, from ‘playful’ houses of horror, through places of pilgrimage such as the graves or death sites of famous people, to the Holocaust death camps or sites of major disasters or atrocities. Nevertheless, all such sites or attractions require effective and appropriate development, management, interpretation and promotion. These in turn require a fuller understanding of the phenomenon of dark tourism within social, cultural, historical and political contexts.

More specifically, the nature of many dark sites and, in particular, the conflicts they represent or inspire, point to a number of interrelated issues that demand investigation and understanding. These include the following.

Ethical issues

One question relating to many dark sites and attractions is whether it is ethical to develop, promote or offer them for touristic consumption. For example, significant debate surrounded the construction of the viewing platform at Ground Zero, enabling casual or even voyeuristic visitors to stand alongside those mourning the loss of loved ones (Lisle, 2004). The proposed construction of a large Tsunami Memorial in the Khao Lak Lamu National Park in Thailand has also been highly controversial. Not only is its potential location in a protected area deemed inappropriate, but many question whether such a large memorial should be constructed in the first place (see also Chapter 8). More generally, the rights of those whose death is commoditised or commercialised through dark tourism represent an important ethical dimension deserving consideration.

Marketing/promotional issues

Many dark tourism sites and attractions are, in a sense, ‘accidental’. That is, they have not been purposefully created or developed as tourist attractions but have become so for a variety of reasons, such as the fame (or infamy) of people concerned, the events that once occurred there or even, perhaps, the beauty of a building. Frequently, the popularity of such sites may be enhanced by the marketing and promotional activity of businesses or organisations anxious to profit through tourism; equally, the media frequently play a role in ‘promoting’ dark sites (Seaton, 1996). In either case, greater understanding of the relationship between the site and its marketing/promotion is required.

Interpretation issues

The interpretation of dark sites and attractions, in terms of both the manner in which they are presented and the information they convey, has long been the focus of academic attention. Inevitably, perhaps, greatest attention has been paid to the development and interpretation of Holocaust sites and the dissonance of their (re) presented history (Ashworth, 1996; Ashworth & Hartmann, 2005b). However, dark tourism sites offer the opportunity to write or rewrite the history of people's lives and deaths, or to provide particular (political) interpretations of past events. For example, Cooper (2006) explores the way in which Japan's imperial past is interpreted in the context of Japanese battlefield tourism sites (see also Siegenthaler, 2002).

Site management issues

Many dark sites and attractions are, by definition, places where individuals or numbers of people met their death, by whatever means. There is, therefore, a need to manage such places appropriately based upon an understanding of and respect for the manner of the victim(s) death, the integrity of the site and, where relevant, the rights of the local community in the context of the meaning or significance of the individual(s) concerned and the place of their death to those wishing to visit. It may sometimes be necessary to control or restrict access to a site. For instance, the public are allowed to visit the house and grounds of Althorp, where Princess Diana was born and raised; however, access to her burial place on an island on the estate is not permitted (Blom, 2000). In extreme cases, more drastic action may be required, such as in the case of 25 Cromwell Street, Gloucester, England, the home of Frederick and Rosemary West and site of multiple murders by the couple. In 1996, following their trial and imprisonment, the house was demolished and the site transformed into a pathway to prevent it becoming a ghoulish shrine.

To some extent, these issues represent the basic agenda for the rest of this book. That is, subsequent chapters address these issues and related topics in more detail, exploring in particular their relevance to managing both the demand for and supply of dark tourism experiences. First, however, it is important to consider the meaning of dark tourism, a question that can be addressed from both descriptive/definitional and conceptual perspectives.

Dark Tourism: Definitions and Scope

Although it is only in recent years that it has been collectively referred to as dark tourism, travel to places associated with ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Part 1: Dark Tourism: Theories and Concepts

- Part 2: Dark Tourism: Management Implications

- Part 3: Dark Tourism in Practice

- References

- Index