History

Bonus Army

The Bonus Army was a group of World War I veterans who marched on Washington, D.C. in 1932 to demand immediate payment of a bonus that had been promised to them for their wartime service. The protest turned into a large encampment, which was forcibly dispersed by the U.S. Army under the command of General Douglas MacArthur, leading to public outcry and political repercussions.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Bonus Army"

- Katherine A.S. Sibley(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

The historiography of the Bonus Army march typically focuses on the grievances and disparate straits of the marchers, their encampment in protest, and the subsequent repression of the marchers by active military forces. The story has been most popularly told in Dickson and Allen’s The Bonus Army: An American Epic (2004), but this work lacks some of the historical depth that consideration of the many issues raised here suggests colored 1920s welfare reform and American parsimony towards World War I veterans. These issues provide the context for the emergence of the Bonus Army in 1932, but even that background doesn’t fully tell who was in that army, what became of them, and what impact their march actually had. Perhaps it is as Dickson and Allen suggest and the GI Bill of 1945 was an effort to ward off another march or similar fiasco, but again this argument overlooks the contested politics in which the earlier march occurred. Ortiz, in Beyond the Bonus March and GI Bill: How Veteran Politics Shaped the New Deal Era (2009), however, notes the limited impact Hoover’s actions against the marchers had on public sentiment as well as details the wide array of struggles veterans faced before the GI Bill, further suggesting the distance in causality between the march and the bill. Conclusion Writers and historians contemporary to the 1920s and early 1930s, as well as pre-war progressives and journalists, held the period to be “a time of reaction and isolationism induced by the emotional experience of World War I” (Noggle 1966: 300). They saw it as “an unfortunate interregnum” (Noggle 1966: 302), between the heights of the Progressive Era and the reforms of the New Deal. Continuing today, historians have noted the failure of progressives to secure a post-World War I “burst of social reform” (Murphy 2011: 14)- eBook - PDF

Marching on Washington

The Forging of an American Political Tradition

- Lucy G. Barber(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER THREE A NEW TYPE OF LOBBYING The Veterans' Bonus March of 1932 In February I992, an eighty-six-year-old widow told her story of the Bonus March of I932 to a reporter from the Wenatchee World, a news-paper in central Washington State. Wilma Waters described a time sixty years earlier when her husband, Walter, set off with three hundred of his fellow veterans from Portland, Oregon, on a 3,ooo-mile journey to Washington, D.C. The men hoped they could persuade Congress to is-sue a payment-often called a bonus-promised to them for their ser-vice during the First World War. The payment was not due until I945· But the veterans, out of work amid rampant unemployment, argued that they, as good citizens, deserved the money immediately. Waters's group inspired thousands of others to join them in Washing-ton, where they became known as the Bonus marchers. For nearly three months, they camped in parks and abandoned buildings. They paraded, lobbied, and waited as Congress debated, voted, and ultimately rejected their demands. As Mrs. Waters flipped through the 28 8 pages of her hus-band's book, B.E.E: The Whole Story of the Bonus Army, she recalled the successes of their efforts. But she knew most people's memories of the event were dominated by its conclusion. On July 28, army troops under General Douglas MacArthur drove the Bonus marchers out of the capi-tal city. Even decades later, she mourned that the eviction of the Bonus marchers was so terrible that my husband was afraid that people wouldn't accept the truth. 1 For Mrs. and Mr. Walter Waters, the Bonus March involved far more 75 76 A NEW TYPE OF LOBBYING than just its draconian end. The protests lasted for nearly eight weeks during the summer of 1932 and required much of participants, author-ities, and observers. - eBook - ePub

Beyond the Bonus March and GI Bill

How Veteran Politics Shaped the New Deal Era

- Stephen R. Ortiz(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- NYU Press(Publisher)

In the late 1920s, the Veterans of Foreign Wars appeared destined for historical obscurity. Despite desperate attempts to recruit from the ranks of the more than two million eligible World War veterans, the VFW lagged behind both the American Legion and even the Spanish War Veterans in membership. And yet, by 1932, in the middle of an economic crisis that dealt severe blows to the membership totals of almost every type of voluntary association, the VFW’s membership tripled to nearly 200,000 veterans. Between 1929 and 1932, the VFW experienced this surprising growth because the organization demanded full and immediate cash payment of the deferred Soldiers’ Bonus while the American Legion opposed it. By challenging federal veterans’ policy, the VFW rose out of relative obscurity to become a prominent vehicle for World War veterans’ political activism. As important, by doing so the VFW unwittingly set in motion the protest movement known as the Bonus March. Indeed, the supposedly unprompted Bonus Army that moved on Washington in the summer of 1932 was a culminating response to the VFW’s initiatives over the prior three years. When the American Legion, the largest of the World War veteran organizations, failed to challenge federal policy, veterans first flowed into the VFW and then onto the streets of the capital. And veteran politics, contained throughout the 1920s, burst like a shell into the watershed presidential campaign of 1932.As discussed in the previous chapter, the Great Depression did not trigger veterans’ calls for immediate cash payment of the Bonus. It did, however, impart a new intensity to their demands. While veterans’ arguments for immediate payment hinged on the notion that wartime service unfairly and permanently disadvantaged them economically, they—like many Americans—began to bear the additional burdens brought on by the Depression. As evidence of the immediacy of the economic crisis that veterans were facing, over a nine-day period in January 1930, 170,000 needy World War I veterans applied for first-time loans on their Bonus certificates. Indeed, the scant existing evidence suggests that the Depression disproportionately affected veterans. In May 1931, the Legion issued a report claiming that 750,000 veterans were out of work, some 16 percent of the World War veteran population. More extensive Veterans’ Administration studies conducted in 1930 and 1931 found that veterans experienced a nearly 50 percent higher unemployment rate than nonveterans of the same age cohort. Another Depression-era VA report concluded that veterans experienced longer stretches of unemployment and more dire financial need than did nonveterans. In 1931, American Legion Commander Ralph O’Neil summed up the situation—perhaps a bit too tidily—by proclaiming, “It is reasonable to assume that a majority of the unemployed are world war veterans.”1 - eBook - PDF

Washington

A History of the Capital, 1800-1950

- Constance McLaughlin Green(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

BONUS MARCH leaders to beg quick action on the bonus bill, for, as long as it was tied up in committee, the Bonus Army would continue to expand. Only prompt defeat or passage of the bill would halt the march before it reached overwhelming proportions. When Congress disregarded his plea, he hurriedly prepared for the impending invasion by finding billets for the veterans. Neither then nor later did he doubt that most of them, for all their unmilitary appearance, were ex-servicemen, not the com- munist trouble-makers the administration would in time depict. He got permission to house the first contingent in a vacant department store, induced the Assistant Secretary of the Treas- ury to let others occupy empty buildings scheduled for early demolition on lower Pennsylvania Avenue, assigned some men to empty sheds and warehouses in southwest Washington, and, as he was unable to borrow tents from the Army or the District National Guard, he helped the main body of bonuseers establish a camp adjoining the dump on the mud flats across the Ana- costia, where they set up ramshackle huts made from old packing cases, odd bits of lumber, scraps of canvas, and tin cans. Before the middle of June over 20,000 bonus marchers had collected in the District of Columbia. Glassford issued orders to his subordinates not to harry them. He persuaded the National Guard to lend its rolling field kitchens and elicited money from rich friends to eke out the rations with which sympathizers in every part of the country were supplying the commissariat of this strange, bedraggled army. Thus abetted, Walter Waters, the elected commander of the Bonus Army, and his lieutenants succeeded in maintaining discipline within its ranks. On the Anacostia the heavily populated "Camp Marks," named for a former police chief, ran with a semblance of military order. - eBook - PDF

Serving America's Veterans

A Reference Handbook

- Lawrence J. Korb, Sean E. Duggan, Peter M. Juul, Max A. Bergmann(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

Soldiers burned down the make- shift structures housing the veterans and their families. For the first and only time in our history, army tanks rode through the streets of America’s capital. Later that night, MacArthur’s force cleared out the main BEF camp in Anacostia. The bonus march was over. 37 But the bonus issue would not die. Congressional bonus advocates made another attempt to legislate the immediate payment of the bonus, led again by Wright Patman. But in May 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, having swept Hoover out of office on the promise of “new deal” for the American people, personally delivered a veto message to Congress. After stating the usual fiscal rationale against immediate payment, FDR went to the nub of his argument: “Able-bodied veterans should be accorded no treatment different from that accorded to other citizens who did not wear a uniform during the World War.” In FDR’s view, the benefits the veterans were asking for should be guaranteed to all citizens. He instead advocated the passage of social security legislation to protect “all workers against the hazards of unemployment,” including vets. 38 Roosevelt’s priority was fighting the depression. As he explained, “The veteran who is disabled owes his condition to the war. The healthy veteran who is unemployed owes his troubles to the depression.” The House re- jected Roosevelt’s argument, but the president convinced enough people in the Senate to sustain his veto. Early in January 1936, however, the Con- gress overwhelmingly passed an immediate payment measure. Seeing the handwriting on the wall, FDR issued an obligatory veto that was promptly overridden in convincing fashion. World War I vets would receive govern- ment bonds $50 in worth, to be either held until 1945 or cashed in on June 15. An average veteran got $583 in bonus cash, which cost the gov- ernment around $1.1 billion. The bonus payment wound up providing almost one percent of gross national product in economic stimulus. - eBook - ePub

The Wages of War

When America's Soldiers Came Home: From Valley Forge to Vietnam

- Richard Severo, Lewis Milford, Richard Severo, Mark Crispin Miller(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Open Road Media(Publisher)

Waters, who was reasonably good at reading between the lines of Washington newspapers, suspected that some within the Federal Government were indulging in a bit of red-baiting, trying to make it seem as though the veterans were not really what they said they were. “You and your Bonus Army have no business in Washington,” Secretary Hurley told Waters and other marchers in a meeting. “We are not in sympathy with your being here. We will not cooperate in any way with your remaining here. We are interested only in getting you out of the District.…”Waters didn’t know it then, but a secret Army intelligence report confirmed his suspicions about red-baiting. The report, bizarre even for Army intelligence, stated that “the first bloodshed by the Bonus Army at Washington is to be the signal for a communist uprising in all large cities thus initiating a revolution. The entire movement is stated to be under communist control, with branches rapidly developed in commercial centers.”The Government reaction to the veteran problem seemed awfully well tailored. Apparently, it benefited from considerable coordination. The message was that even veterans who were not communists were a burden to the rest of the country. As the Hoover Administration beat the red drum in Washington, Army Major-General James O. Harbord told the “first annual meeting” of the National Economics League in New York City that by 1945, payments to veterans and their families would reach $2 billion. The league sought to eliminate at least $450 million a year in payments to Spanish-American and World War veterans “who suffered no disability in war service.” The same day that it reported Harbord’s speech, the Washington Evening Star editorialized that “the real design of those who are now using the bonus plea as an excuse for agitation is to attract attention, even at the cost of a possible riot at the Capitol.”Troublemakers were everywhere, if Washingtonians believed what they read in their newspapers. On July 27, a wire service story datelined Pontiac, Michigan, reported that police were looking for a “radical” group which was making uncomplimentary statements about the nation’s banks. It was fanciful to suggest that any rumors circulated by radicals would make banks more distrusted than they were already, but such was the way of it in Pontiac and Detroit. That set it up rather nicely: communists or maybe fascists were running the veterans’ Bonus March and those veterans who were not communists or fascists were greedy and, worse still, were even bank-haters. - eBook - ePub

Wars Civil and Great

The American Experience in the Civil War and World War I

- David J. Silbey, Kanisorn Wongsrichanalai(Authors)

- 2024(Publication Date)

- University Press of Kansas(Publisher)

48Despite pleas from various quarters, President Hoover refused to budge, claiming that if they received their bonuses early, the veterans would spend it on “wasteful expenditures.” The president again brought up the issue of dependence, noting that an immediate payment would “break the barriers of self-reliance and self-support in our people.” In order to demonstrate their plight and urge the president and Congress to reconsider their decision, around twenty-five thousand veterans, the so-called Bonus Army, marched on and sheltered in abandoned federal buildings in Washington, DC, in the summer of 1932 . When negotiations to clear the capital failed, army units under the command of Gen. Douglas MacArthur used bayonets and tear gas to clear out the veterans from their positions. According to one historian, the clearing out of the Bonus Army “marked the final betrayal by a country ungrateful for their sacrifices.”49 The incident (perhaps unjustly) also gave contemporary Americans the impression that President Hoover did not care about their plight and “remains historical shorthand for the failure of the Hoover presidency.”50The Bonus March fiasco did teach national leaders some key lessons. Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had benefited from Hoover’s mismanagement of the affair to become his successor, faced the Bonus Marchers in the summer of 1933 when they returned to the nation’s capital. Having just signed the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) legislation into law, Roosevelt issued an executive order that created a separate division of the CCC for veterans who had received honorable discharges. For their toil in the nation’s forests, they would receive food, shelter, and $30 per month. But jobs for some veterans did not make up for FDR’s slashing of veterans’ benefits. Great War veterans became a key bloc that kept pressuring the government for additional help during the early 1930 s.51 - eBook - ePub

The Laws That Shaped America

Fifteen Acts of Congress and Their Lasting Impact

- Dennis W. Johnson(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Nevertheless, the House of Representatives passed the Patman bill, 211–176, with most Democrats voting for and most Republicans against. Bonus marchers, scattered throughout the House gallery when final passage came, broke into applause, although warned repeatedly against any grandstanding. Then some 6,000 bonus marchers joined in a solemn funeral procession for Representative Edward E. Eslick (Democrat–Tennessee), an ardent supporter of the bonus bill, who had died on the floor of the House days earlier. Senator J. W. Elmer Thomas (Democrat–Oklahoma), a chief sponsor of the bill, was hopeful that the Senate would accept it, but, on June 14, the upper body resoundingly rejected the bonus bill, 62–18.In early June 1932, with the arrival of the Bonus Army, Congress and Hoover secretly sought to give the demonstrators army cots, blankets, tents, food, and medical supplies; the U.S. Army, however, protested, telling Congress that such gestures would violate the “basic principles” of the Army and the War Department toward this motley so-called Bonus Expeditionary Force.31 In June 1932, General Douglas MacArthur, Army chief of staff, wired all corps area commanders that, if any Bonus Army marchers came through their areas, the commanders were to determine if any communists were present. MacArthur added that he wanted the names of those with “known communist leanings.”32In early July 1932 Congress appropriated funds to help veterans return to their homes; many of the estimated 12,000 veterans in Washington left for home. Congress adjourned for the year on July 16, without passing a bonus bill.33 On July 21, with 5,000 veterans still in Washington, members of the Bonus Expeditionary Force were informed that they were to be evicted from a government-owned building on Pennsylvania Avenue. The warning was reiterated on July 27, and eviction began the next morning. One building was cleared, but then a fight broke out between 200 marchers and city police, and two marchers were killed. By that afternoon, the District Commissioners reported to President Hoover that the situation was out of control.Hoover, waiting an hour for the request to come in writing, then ordered MacArthur to clear the area. Federal cavalry, six tanks, and a column of infantry were called in. MacArthur was supposed to secure the contested buildings and contain the marchers at their bivouac site on the Anacostia River flats, but instead he used tear gas to rout the marchers from their base and he allowed the city police to burn down their forlorn camp. - eBook - ePub

Paid Patriotism?

The Debate over Veterans' Benefits

- James T. Bennett(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

114Not every marcher was a down-and-outer. There were a few professional men in the ranks, for instance attorney John Hazel of Atlanta, who spoke in eminently reasonable, perhaps even excessively mild, terms to the Charlotte Observer:We do not have any purpose in mind of trying to frighten or overawe Congress into passing the Bonus bill . . . We are simply making our way to the Capitol in order to present personally our pleas to our representatives and senators. We feel that our journey to Washington may have a good effect in that it will acquaint them as in no other better way, perhaps, with the terrible need of the great many of the nation’s finest soldiers of the World War.115Phrased this way, the BEF sounded no more threatening than a gaggle of Kiwanians from Duluth. This is not to say that the Bonus Army didn't include its share of frauds. The chieftain of the 1,500 strong Southern California contingent, one Royal W. Robertson, cut a striking image in his neck brace—which "resulted from falling out of a hammock while in training" in the navy.116The Bonus Marchers had the good fortune to be met by Brigadier General Pelham D. Glassford, chief of police in the District of Columbia, who was a most unusual Washington bohemian: a West Pointer (where his friends included Douglas MacArthur), veteran of WWI, and also a watercolorist, a ladies' man, a former circus barker, a tinkerer, and a defender of the First Amendment. His modus operandi, as the admiring historian Daniels writes, was to assume that "demonstrators were reasonable human beings, with whom one could conduct a dia-logue."117 He was deeply sympathetic to the men, helping to provision their makeshift settlements and treating them with dignity.Even before Waters and his Oregonians arrived, Bonus Marchers had set up shop in the District. On May 26, 500 veterans gathered in Judiciary Square and after hearing two speeches from the intelligent and affable police chief ("Fellow veterans and comrades. . . . I shall be very glad to do everything I can for you. I can't tell you how much in sympathy I am with you and all others who are unemployed."118 ) actually elected Pelham Glassford, a VFW member, their secretary treasurer. Glassford took it on himself to see that the Bonus Marchers were provided with donated food, medical care by volunteers, and bed sacks from the Department of War—assistance that came with the blessing of President Hoover. Glassford’s motorcycle-borne policemen distributed iodine pills and even advice on how best to dig a latrine, which the men dubbed "Hoover Villas."119 - eBook - ePub

- Don Lohbeck(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Arcole Publishing(Publisher)

On July 29, James Ford, Communist candidate for vice president, exhorted a conference of veterans to resist the United States Army; the hall was raided and Ford and forty-two others were arrested. This raid closed the Communist siege of Washington. The clash with the United States Army was “just what the Communists wanted. It was what they had conspired to bring about. Now they could brand Hoover as a murderer of hungry, unemployed veterans.” {31} Immediate press reaction to the eviction of the Bonus Army can be summarized by two quotations: (1) from the Washington Times, July 29, 1932, as follows— The radical elements accompanying the bonus seekers have accomplished their objects....No group of a few thousand citizens, no matter how worthy, can be allowed to defy flagrantly the rules and regulations which 120,000,000 have set up for the preservation of peace, order and comfort....The deepest sympathy for these men in their plight of poverty remains. That they had to be driven away to their homes by force is regrettable. Nevertheless the time always comes when the majority must express itself forcibly to repulse attacks by a predatory minority. And, (2) from Time Magazine, August 8, 1932, as follows— Most of the nation’s press approved the manner in which the President had dealt with its Bonus Expeditionary Force. Public blame, if any, was placed less on members of the Bonus Expeditionary Force than upon those Senators and Representatives who by agitating full and complete bonus payments had lured veterans to Washington and kept them there with false hopes and promises. The year 1932 was a presidential election year, however—and the propaganda machine was soon at work forming the public’s opinion. “We had found it difficult to believe that American citizens would use the liberties guaranteed by our form of government to attempt to destroy that government,” Hurley said later - eBook - PDF

Bylines in Despair

Herbert Hoover, the Great Depression, and the U.S. News Media

- Louis W. Liebovich(Author)

- 1994(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

11. "Troops Balk 'Bonus Army,' " Chicago Tribune, May 24, 1932, p. 1; "If This Is a Lark, What's a Riot?" Chicago Tribune editorial, May 25, 1932, p. 12... 12. "Railroad Again Fools Bonus Band, Unhooks Engine," St. Louis Post- Dispatch,May 23, 1932, p. 1. 13. "National Guard Ordered to East St. Louis Where 'Bonus Marchers' Seized a Train," The New York Times, May 24, 1932, p. 1. For other examples of stories or editorials, see "Veterans Resume March on Capitol," Portland Oregonian, May 25, 1932, p. 1; "Problems of the Bonus Hike," Chicago Daily News editorial, May 28, 1932, p. 10; "Veterans Give Up Freight Cars As Guard Called Out," New Or- leans Times-Picayune, May 24, 1932, p. 2; "Veteran Bonus Army Fails in Threat to Seize Train," Washington Post, May 22, 1932, p. 1; "Bonus Veterans Due in Capital Next Week," Post, May 25, 1932, p. 1. 14. See "Washington Police Trail War Veterans" and "Militia Rushed As 300 Vets Capture Train," San Francisco Examiner, May 24, 1932, pp. 1, 2. 15. Waters, B.E.F., pp. 70-72; Daniels, Bonus March, pp. 87-122; Lisio, Pres- ident and Protest,pp. 53-62. 16. Theodore Joslin diary, May 26, 1932, entry, Joslin Papers, Box 10, HHPL. 178 Bylines in Despair 17. lisio, President and Protest,pp. 73- 74, 81. 18. Joslin diary, June 9, 1932, entry. 19. Ibid. 20. Herbert Hoover. The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover. The Great Depression 1929-1941,vol. 3 (New York: Macmillan, 1952), p. 225. 21. Waters, B.E.F., p. 13. 22. "A Veteran Speaks His Mind," American, November 1932, p. 20. 23- Daniels, Bonus March, pp. 50-52. 24. Walter Davenport, "But the Dead Don't Vote," Colliers, June 11, 1932, p. 47. 25. Lisio, President and Protest, p. 87. 26. Ibid., p. 141. 27. Waters, B.EF.,,p . 94. 28. Washington Posteditorial, June 3, 1932. 29. "Kangaroo Court Marital Warns Red Chieftains" and "Veteran Forces Defy Request to Leave Thursday," Washington Post, June 5, 1932, pp. 1-2. 30. "Reds Held Leaders of Bonus Marchers," The New York Times, June 3, 1932, p. - eBook - PDF

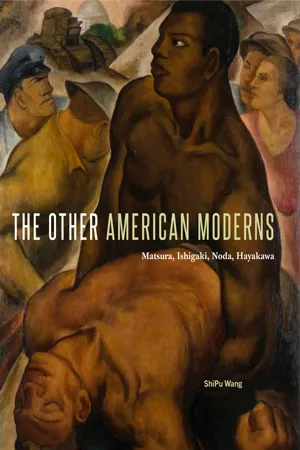

The Other American Moderns

Matsura, Ishigaki, Noda, Hayakawa

- ShiPu Wang(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Penn State University Press(Publisher)

9 In the end, opponents of the march pressured the Hoover administration to take action to dissolve the encampment, precipitating the D.C. authorities’ eventual clash with the marchers (figure 26). Referred to also as the “Bonus Incident,” this historic mass demonstration cap- tivated the nation’s attention in 1932 and fueled the artistic production of American progressives and leftist intelligentsia, with whom Ishigaki had long been allied. The eventual confrontation between the unarmed veterans and the government’s over- powering show of force provided artists yet another example of the perceived refusal of the establishment (thought to be controlled by capitalist profiteers) to take care of its economically disadvantaged people and of its blatant disregard for their political disenfranchisement. In The Bonus March, Ishigaki included all the actors involved in the conflict: the marchers, the men in uniform, and the tank, representing the D.C. police and the U.S. Army troops, commanded by General Douglas MacArthur, then the army’s chief of staff. MacArthur was said to have proceeded with the removal of the marchers from the Anacostia area by force despite President Hoover’s concern over his administration being perceived as acting too harshly. The protesters could not match the firepower of the troops; numerous veterans were injured, and several were killed. 10 In Ishigaki’s representation of the confrontation, the Capitol Building 26 Bonus Army shacks burning, Anacostia Flats, 1932. The makeshift shacks were set ablaze during the forced removal. It was unclear how the fire was started, but the image of raging fires destroying the marchers’ camp, with the Capitol Building looming in the distance became an iconic illustration of the government’s use of force against its defenseless citizens. National Archives.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.