History

League of Nations

The League of Nations was an international organization established after World War I with the goal of promoting peace and preventing future conflicts. It aimed to achieve this through collective security, disarmament, and negotiation. Although it faced challenges and ultimately failed to prevent World War II, the League laid the groundwork for the establishment of the United Nations.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "League of Nations"

- eBook - ePub

- Erik Goldstein(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Chapter Four The League of NationsDOI: 10.4324/9781315840703-4The horrors and vast scale of the First World War spurred the development of ideas for ways to prevent the recurrence of conflict. Interest in some form of general international organization had been discussed by several generations of publicists.1 The collapse of the old concert system, combined with hopes of creating lasting peace and security, now impelled the Allied powers to convert these proposals into policy. By the time the Armistice was signed it was clear that the creation of a League of Nations would be part of any peace settlement. Woodrow Wilson had called for such an organization in the Fourteen Points [Doc. 3], as had Lloyd George in his Caxton Hall speech of January 1918 [Doc. 2] when he declared the creation of a similar body as being among Britain’s three preconditions for establishing a permanent peace. The French government had also been working on plans for an international organization.The concept of a League of Nations grew out of several earlier developments. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries philosophers such as William Penn and Emmanuel Kant, among others, had proposed schemes for perpetual peace. The nineteenth century saw substantive steps to promote international peace, one of which was the search for mechanisms to prevent war. This effort reached a critical stage at the Hague conferences of 1899 and 1907, which sought to establish judicial mechanisms for resolving conflict. A second step was the growth of international organizations that promoted international cooperation, beginning with the Universal Postal Union in 1875. While non-political, they provided evidence of the efficacy of international cooperation. The Allied experience of wartime cooperation through joint Allied commissions controlling raw materials, shipping and trade provided further evidence of the utility of cooperation. An added factor was that many blamed the secret diplomacy of the prewar era for the drift to war and Wilson had proposed that the solution to this was Open Diplomacy. It was envisaged that the League would provide a forum for such open diplomacy, where all treaties and agreements between states would be deposited and published. During the war public pressure groups emerged to support the idea, such as the League to Enforce Peace in the United States and the League of Nations Society in Britain. - eBook - ePub

Routledge History of International Organizations

From 1815 to the Present Day

- Bob Reinalda(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Part VILaying down the path of collective securityThe First World War, the League of Nations founded (1919) and the interwar period

The sixth part deals with the First World War and the interwar period. The war caused a break in the development of international organizations after the ‘long’ nineteenth century (until 1914), but it also involved a new initiative. The founding of a ‘League of Nations’ was widely discussed during the war by both citizens and politicians and became part of the institutional strategy devised by the US. The outcome of that strategy was, however, determined not by the US, but by the balance of power between the principal victors at Versailles, where the Covenant of the League of Nations was drawn up (Chapter 15 ). The League proved to be a suitable medium to restore relations in places where measures had been taken during the peace negotiations, but where acute tensions still existed. This resulted in arrangements such as temporary administration, conflict settlement and the accommodation of large numbers of refugees. Efforts to disarm, however, remained the domain of the great powers, despite attempts by the League of Nations to play a part. The League had barely any grip on the political and military developments of the 1930s because the great powers took little notice of it (Chapter 16 - eBook - ePub

The Consequences of the Peace: The Versailles Settlement

Aftermath and Legacy 1919-2015

- Alan Sharp(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Haus Publishing(Publisher)

3The League of Nations and the United Nations

‘What are the purposes that you hold in your heart against the fortunes of the world?’Woodrow Wilson1The 20th century witnessed two attempts to create a new order in international affairs, the League of Nations after the First World War and the United Nations Organization in the wake of the Second. Inevitably each was much influenced by the circumstances in which it originated but there was a real ambition on both occasions to produce an institution that would inhibit, if not prevent, mankind from resorting to war – a task that took on added urgency after the explosion of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 announced the arrival of weapons which really did have the capacity to destroy life and civilizations on a global scale. In many ways, however, the nuclear age was only the realization of fears which the inter-war period also entertained. The British government’s grossly inflated pre-1939 estimates of the scale of civilian casualties expected from sustained German bombing, probably also using gas and chemical weapons, were already little short of cataclysmic.There was thus a determination, after both these unprecedentedly destructive conflicts, to establish structures and codes of conduct that would encourage alternative modes of dispute resolution. The League did not fulfil the expectations of its advocates, which were overambitious and unrealistic, yet the great powers still established a replacement after the Second World War. In its turn, the United Nations has also suffered disappointments and experienced frustrations when rendered powerless by the determination of the major powers either to block the initiatives of rivals or to act independently. Nonetheless, despite their inability to deliver the world peace their most hopeful supporters envisaged, both the League and UN have helped to transform the norms and conduct of international relations and represent a remarkable evolution from pre-1914 diplomacy. - M. Patrick Cottrell(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

For these and other reasons, the League continues to influence inter- national relations today in ways that are often overlooked. 2 While many refer to the League of Nations as an “experiment,” very few make the same reference to the United Nations. This may be in part because the United Nations had the benefit of learning from the League experience. As Woodrow Wilson himself remarked, “The League must grow, it can- not be made.” Indeed, the League idea continues to grow today in the modern United Nations. i. origins of a grand experiment The basic story of the League is well known. 3 The victors of World War I founded the League of Nations in 1919 as the first international institution to embody the collective security approach to the use of military power. Proponents envisioned it as the structure that could enable the “war to end all wars” slogan to ring true. However, from its inception, the League of Nations experienced a string of severe setbacks that undermined its legitimacy and ultimately resulted in its collapse. While there can be no doubt that the League failed in many fundamental respects, it also left a lasting impact on future events that transcends the conventional wisdom and helps illuminate the phenomenon of replacement. Weighing this impact first requires the recognition that the League experiment rested on ideas that had been percolating long before the Great War. The purpose of this section is thus to locate the League in a broader historical and cognitive evolutionary process, which both legitimated a set of ideas that had been percolating for years and institutionalized them in a way that reflected the political exigencies of the post-war settlement. For the League embodied the conflicting sentiments of the time – a longing for a sustainable peace in the future and a thirst for retribution for the recent past. 2 The primary focus of this chapter is on the League as a security organization.- eBook - PDF

Imposing Economic Sanctions

Legal Remedy Or Genocidal Tool?

- Geoff Simons(Author)

- 1999(Publication Date)

- Pluto Press(Publisher)

Peace conferences were held throughout the nineteenth century, often attracting international participation with delegates from many countries. Now various themes (the peaceful settlement of disputes, sanctions against recalcitrant states, the growing importance of international law, and so on) were being considered that together would prepare the way for the establishment of international bodies that would symbolise the community of nations. Free trade was being recommended, rightly or wrongly, as a route to international peace; while various international organs were being created with powers over national administrations: for example, the Danube Commission (1856), the International Telegraphic Union (1865), the International Institute of Agriculture (1905), and the International Health Office (1907). At the same time various bodies (for example, the Brussels-based Institut de Droit International , founded in 1873) were working on the development of international law. In 1936 Bertrand Russell reminded us that his father, Lord Amberley, had in 1871 advocated a version of the League of Nations, ‘with the whole apparatus of economic and military sanctions’. 1 Conferences at The Hague (1899 and 1907), attended (respectively) by 26 and 44 nations addressed questions relating to weapons usage, arms limitation, the rights of neutral shipping (highly relevant to the issue of economic warfare) and other matters. A third Hague conference was aborted by the onset of the First World War, but by now the ground had been well prepared for the creation of the League of Nations. One of the main architects of the League was Thomas Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924), a law professor and the twenty-eighth President of the United States. On 8 January 1918 he announced to the US Congress the conditions that should govern the peace at the end of the Great War. - Elizabeth Cobbs, Edward Blum, Jon Gjerde, , Elizabeth Cobbs, Edward Blum, Jon Gjerde(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

’” In Germany, prominent activists had started planning an “ international union of states ” even earlier, shortly after war commenced. By November 1914, three organizations had devised plans for a “ peace free from recriminations ” and based on a new international body. Chancellor Hollweg expressed his sympathy with such ideas, but told the German author of a popular book titled Bund der Volker (League of Nations) that he was constrained by “ constitutional militarism. ” … James Bryce, former British ambassador to the United States, sponsored one of the most influential schemes for a League of Nations. Lord Bryce and his colleagues commenced discussions at the end of 1914. From the very start, they contemplated national self-determination, arms reductions, and a League of Nations. Historian Martin Dubin argues that scholars “ seem not to understand how … early and pervasive an influence ” the Bryce Group exerted. Its plan for a league equipped with coercive power attracted attention on both sides of the Atlantic. It may have stimulated formation of the U.S. League to Enforce Peace that began six months later, in June 1915. In the United States, former Republican president William Taft assumed leadership of … the League to Enforce Peace. For good luck, and to symbolize the continuity they saw between the federal structure of the United States and a possible counterpart in Europe, organizers timed the June 17, 1915, inaugural conference with the anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill. Three hundred delegates met in the same Philadelphia hall where revolutionaries had signed the Declaration of Independence and the American Constitution. They abstained from judgment on the war then in progress, but expressed their conviction that afterward it would “ be desirable for the United States to join a League of Nations ” binding the members to compulsory arbitration.- eBook - ePub

Lord Robert Cecil

Politician and Internationalist

- Gaynor Johnson(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

A state that breached this agreement should expect to be subject to the collective military might of the other signatory powers. Second, an international body known as the League of Nations would be brought into being to ensure that hostilities did not break out before sufficient time had elapsed for the conference to meet. The League of Nations would also act as a mouthpiece for public opinion opposed to the outbreak of the conflict and as a means of promoting the democratic agenda of the Allies. 76 Cecil’s paper was received ‘respectfully rather than cordially’ and failed to command majority support. 77 Undeterred, however, he used its substance in a speech on the League at his inauguration as Chancellor of the University of Birmingham on what proved to be the day after the Armistice, 12 November 1918. 78 By the autumn of 1918, Cecil also had well-established links with the League of Nations Society and with the League of Free Nations Association. 79 The latter had been created in high dudgeon after the former had rejected a league based on the wartime alliance, but had agreed to the merger because the imminent end of the war made the disagreement irrelevant. 80 Indeed, the two organisations held a successful joint rally in Central Hall Westminster on 10 October 1918, its climax being a speech by Viscount Grey. 81 The reception accorded to the rally persuaded the two organisations to amalgamate to form the League of Nations Union (LNU), dedicated to promoting ‘the formation of a World League of Free Peoples for the securing of international justice, mutual defence and permanent peace’. 82 Significantly, Lloyd George agreed, along with Asquith, Grey and Balfour, to serve as an honorary president. 83 Two weeks later, a parliamentary LNU group was established, with Cecil’s brother-in-law, Lord Selborne, as its leader. The work of the new organisation was endorsed by a meeting at Lambeth on 29 October 1918 of an inter-denominational gathering of Church leaders - eBook - ePub

Towards the Peace of Nations

A Study in International Politics

- Hugh Dalton(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

HAPTER VTHE League of Nations

I

Between the pre-war international anarchy and a World State, the League of Nations is a compromise and, perhaps, a transition. An inevitable transition, if the World State is destined to be born; a pale substitute, if it is for ever unattainable. But this League, full of promise and full of imperfections, is a fact, which the World State, as yet, is not. It is the most ambitious piece of international, or inter-State, machinery which has yet been built and, as such, it deserves close and objective study. But such study should, in part at least, be carried out upon the spot. A priori judgments from a distance, or from cold print alone, are apt to be misty, pedantic and out of scale. It is difficult to visualise the League or to estimate its qualities fairly without having visited Geneva, seen the Council, the Assembly and the Commissions in session, apprehended the environment of human contact, negotiation, gossip and intrigue, and made personal acquaintance with members of the League Secretariat and of the staff of the International Labour Office.11 This was certainly my own experience and I note that it was also that of Mr. Brailsford, sometimes a very severe critic of the League. “The fact is,” the latter writes, “that Geneva gains on a near acquaintance. One forgets in intercourse with the Secretariat the dismal impression which the insincerities of the Great Powers have left on one’s mind…. At Geneva one learns to realise that there is a League within the League. There is the Council, which evades its destiny, and there is the Secretariat, which cherishes a proper, ambition for the League. The world has had a good deal of experience in the difficult job of setting up international administrations of one kind or another. Few of these experiments have ever been a conspicuous success, chiefly, I suspect, because they were usually controlled by diplomatists or by men, that is to say, whose life work was a training in the promotion of exclusively national interests. Fortunately for the League, few of the men who form its Secretariat came from the diplomatic service, and the exceptions—above all Sir Eric Drummond at its head—have shown themselves big enough to take the international view. It arises naturally in the intimate cosmopolitan life of this little society. Working constantly together, they have come to pursue one united purpose, the success of the idea to which they have devoted their lives. It was not surprising to find that Swedes and Norwegians possessed this international outlook; small nations have an obvious interest in its growth throughout the world. But I was astonished at the manifest sincerity of some of the staff who belonged to the great armed Powers, notably the Frenchmen and the Japanese. If the League grows but slowly in authority, it will not be for lack of a devoted and honestly international Civil Service. Common work has wrought this miracle, common education may be the key to the training for yet more important work of the servants of the international idea, whom the world will need in years to come…. One day the world may create its central university in the shadow of the League.” (New Leader, - eBook - PDF

The Institutional Veil in Public International Law

International Organisations and the Law of Treaties

- Catherine Brölmann(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Hart Publishing(Publisher)

a separate legal order apart from the sphere of general international law. 96 Put in terms of this book, organisations were predominantly ‘open’ structures. 97 3.3 THE League of Nations ERA 3.3.1 Institutions The twentieth century has been described as ‘the era of establishment of international organization,’ as opposed to ‘the era of preparation [ . . .]’ that was the nineteenth century. 98 The League of Nations and the Interna-tional Labour Organization (ILO), their constitutive instruments being included in the Versailles treaties, 99 were the most prominent new intergov-ernmental institutions. They can indeed be seen as a consolidation of earlier trends, both in form and effect. Form-wise, the ILO built on the model of the nineteenth-century technical organisations. 100 The League of Nations relied, more loosely, on the examples of the international Bureaux (for its Secretariat), the Concert of Europe (for its Council) and the Hague Conferences (for its Assembly). 101 What was new about it was ‘the idea … to force the coalescence of pre-1914 relations into a “system”’. 102 In general terms both organisations were more influential in the interna-tional arena than their predecessors had been. In the case of the ILO this occurred primarily within the legal order of the organisation, which displayed an unprecedented degree of centralisation. 103 The League was 96 Cf Bederman, above, note 54, at 344–347 (on pre-war doctrine). 97 See ch 2 above – this is a perspective conveyed by the then common denomination ‘association of states’; see eg Pasquale Fiore’s Codice of 1889, § 681; cf the terminology later employed by Lauterpacht (section 8.1.2 below); and the argument advanced by the Interna-tional Law Commission in relation to the 1986 Convention that the definition of ‘group of states’ include ‘international organisation’ (section 10.3.1 below, s.v. arts 52 and 76). - eBook - PDF

International Relations and the Labour Party

Intellectuals and Policy Making from 1918-1945

- Lucian Ashworth(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- I.B. Tauris(Publisher)

Linked to the second point was the question of the va-lidity of the Permanent Court of International Justice, and especially the signing of the Optional Clause, by which the signatory state would recog-nise the decisions of that Court as binding. Many of these issues lay un-resolved in 1931 when the full force of the economic depression hit the world economy. In this sense, the League, as the first serious attempt to create a truly global security organisation, was very much a work in pro- T HE L EAGUE AND THE N EW D IPLOMACY 97 gress during its first decade. Statesmen were still unsure how it should be used, and League officials were managing an organisation whose powers were as unclear as they were unprecedented. Thus, the League did not en-ter the 1930s fully equipped to deal with the problem of aggression. Rath-er, after eleven years of existence, it was still being developed. In 1927 Philip Noel Baker asked if the League’s institutions would ‘be given time to build up their strength before the catastrophe of a new war sweeps them all away?’ 60 Six years before Hitler’s coming to power even the strongest of the League’s supporters knew that there was much work to be done before the League was up to the test of a serious war-threatening crisis. The United Nations would, after that deluge, benefit from the Lea-gue’s learning curve. Of course, these five ‘gaps’ were all related. In fact, from the point of view of the majority on the Advisory Committee and the group around Arthur Henderson, disarmament, arbitration and sanctions formed an inter-related triangle in which one could not be realised without the other two. 61 Disarmament was not going to be a serious prospect until a system of arbitration and conciliation that removed the necessity for armed def-ence had been put in place. 62 The question of arbitration and conciliation carried with it the question of what to do if the methods of peaceful res-olution failed. - eBook - PDF

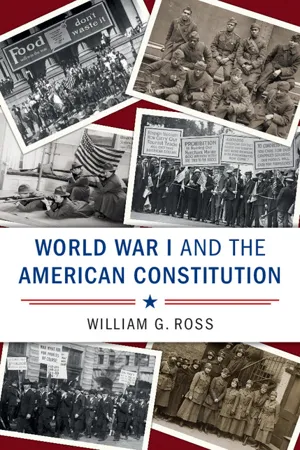

- William G. Ross(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

125 Turner, “Peace League or War League?,” 140. 126 “Agitation for a League,” The New Republic, March 15, 1919, 201. 127 Turner, “Peace League or War League?,” 140, 141. The League of Nations 341 Many opponents also denounced the League as a vehicle by which banks and large corporations could manipulate international finance. Johnson privately alleged that “the League of Nations is just a huge war trust, backed by international capitalists, who prefer to have an interna- tional clearing house, where they can deal with and control a few indivi- duals instead of many in different nations.” 128 As Yale Law Professor Edwin M. Borchard privately remarked to LaFollette, the League would call upon young American men to “die to collect the money due foreign investors.” Borchard also expressed fear that the League would suppress new political ideas by labeling them Bolshevik. 129 A socialist newspaper denounced the League as “a gentleman’s agreement of Allied capitalists and imperialists to exploit the peoples and resources of the world without getting in each other’s way.” 130 Opponents of the League also argued that its collective security features would subject the United States to severe financial burdens. 131 Many African Americans objected to the treaty because they believed that it would stifle the self-determination of colonized peoples. 132 The Crisis, however, believed that the League was “absolutely necessary to the salvation of the Negro race. Unless we have some super-national power to curb the anti-Negro policy of the United States and South Africa, we are doomed eventually to fight for our rights.” 133 The League also suffered from objections to various provisions in the general treaty of peace, to which the covenant was linked. 134 Among Americans, the most controversial part of the treaty may have been the cession to Japan of the Chinese province of Shantung, a former German protectorate with a population of 30 million.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.