History

Stalin's Cult of Personality

Stalin's Cult of Personality refers to the extensive propaganda and glorification of Joseph Stalin during his rule over the Soviet Union. This involved the promotion of his image as a heroic and infallible leader, with his personality cult permeating all aspects of Soviet society. It served to consolidate his power and control, while also fostering a climate of fear and obedience among the population.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Stalin's Cult of Personality"

- eBook - ePub

The Political Thought of Joseph Stalin

A Study in Twentieth Century Revolutionary Patriotism

- Erik van Ree(Author)

- 2003(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

12 The cult of personalityOne of the main characteristics that Stalinism became notorious for was the cult of the leader’s personality. Stalin was presented in books, journals and newspapers, in prose and poetry, in song, painting and sculpture, as a flawless genius and hero, on a par with similar extraordinary historical personalities like Karl Marx and Vladimir Il’ich. The cult reflected the dictatorial power that its object established in real life. Stalin established this personal dictatorship by crusading against all informal centres of power with a degree of autonomy, in the party, in the regions and in state institutions. He waged this crusade under the banner of struggle against the old “family traditions,” which he denounced even before the revolution. The struggle against entrenched “families” (autonomous groups based on personal relations, friendship and mutual protection) reflected his harsh views of how a party should function as well as his strategy for personal rule.At the party congress in 1927, the leader complained that problems were often solved “in a family way, as if at home.” When Ivan Ivanovich makes a mistake, his friend Ivan Fedorovich “does not want to criticise him, bring to light his mistakes, correct his mistakes.” The latter Ivan hoped that his leniency would be rewarded in the future when he was in trouble. Was it not ironic, Stalin asked, that the bolsheviks, who were out, in Marx’s words, to storm the heavens, were not prepared to storm each other? They should understand that bad things do not disappear from themselves. “That which dies, does not simply want to die, but it struggles for its existence, defends its lost [otzhivshee] cause.” And conversely, that which is newly born must shriek and cry out to defend its right to exist. Correspondingly, true leadership was to combat, to spare no one irrespective of friendship, and to reject the tendency to “swim with the current.”1 - eBook - ePub

Discontents

Postmodern and Postcommunist

- Paul Hollander(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

23The Cult of Personality in Communist States 1Virtually every communist system, extinct or surviving, at one point or another, had a supreme leader who was both extraordinarily powerful and surrounded by a bizarre cult, indeed worship. In the past (or in more traditional contemporary societies) such cults were reserved for deities and associated with conventional religious behavior and institutions. These cults although apparently an intrinsic part of communist dictatorships (at any rate at a stage in their evolution) are largely forgotten today.The term was born of an attempt of Nikita Khrushchev to explain away (in a highly un-Marxist manner) the deformation and defects of the Soviet system under Stalin. Khrushchev introduced it at the 20th Party Congress in 1956 to describe and define Stalin’s misrule and notorious abuse of power. The officially enforced cult of him was one aspect of his misrule. As Khrushchev saw it, or wished his audience to see it, Stalin’s personality—including his desire to be an object of a cult—was responsible for everything that went wrong with the Soviet system.Stalin, Mao, Castro, Ho Chi Minh, Kim II Sung, Enver Hoxha, Rakosi, Ceascescu, Dimitrov, Ulbricht, Gottwald, Tito and others— all were the object of such cults. The prototypical cult was that of Stalin which was duplicated elsewhere with minor variations. Arguably some other cults and the intensity of the worship they entailed— notably those of Mao, Kim II Sung and Hoxha—exceeded Stalin’s.It is a surprising aspect of the study of communist systems—and especially its comparative variety—that this cult has been of little scholarly interest and hardly ever identified as one of their shared, institutionalised characterisic. Why has it received so little attention is in itself an interesting question. Perhaps because of an all too ready acceptance of the claims of these systems as highly rational undertakings (which would be incompatible with such a cult), or with the difficulty of reconciling their official Marxist ideology with a phenomenon such as the cult; possibly this lack of attention may also be connected with Western attitudes which sought to differentiate communist from other totalitarian systems which too had such cults. - eBook - PDF

Stalin

A New History

- Sarah Davies, James Harris(Authors)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

V. Stalin sam o sebe’, p. 113. 89 On the distinction, see Michel de Certeau, The Practices of Everyday Life, trans. Steven F. Randall (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), pp. xii–xiii and ch. 3; Brandenberger, National Bolshevism, ch. 6. 90 See, for instance, Tsentral’nyi arkhiv obshchestvennykh dvizhenii Moskvy (henceforth TsAODM) f. 4, op. 39, d. 165, l. 4; d. 196, ll. 7–37; Davies, Popular Opinion, pp. 167–82. 91 See TsAODM f. 3, op. 81, d. 225, l. 64; f. 4, op. 39, d. 196, ll. 3–5; d. 201, ll. 70–93. 92 See Clark, The Soviet Novel, pp. 14–15, 57. For a similar interpretation of the cult’s aesthetic limitations, see Plamper, ‘The Stalin Cult in the Visual Arts’, p. 11. 93 17 August 1939 diary entry published in Dnevnik Eleny Bulgakovoi, p. 279. Stalin as symbol 269 than a Party history textbook, a fate that clarifies its poor reception on the popular level all too well. But if this may call for a broader reevaluation of the resonance that the cult of personality elicited within Soviet society, it does not alter the fact that between 1929 and 1953 the Party hierarchy invested heavily in the Stalin cult in general, and in his official biography in particular. This case study has demonstrated that the cult was much more of a populist effort than it was an exercise in self-aggrandisement. Stalin and his lieutenants clearly viewed the promotion of charismatic leadership as a way of bol- stering the authority and legitimacy of the Soviet system. A reaction to Party ideologists’ frustration with more orthodox Marxist-Leninist pro- paganda during the 1920s, the Stalin cult was intended to celebrate an individual who would symbolise the Soviet experiment in familiar, per- sonal terms. Regardless of the cult’s actual reception on the mass level, the timing and nature of its emergence indicate that it was genuinely expected to win the hearts and minds of the Soviet populace. 270 David Brandenberger - eBook - PDF

Stalin's World

Dictating the Soviet Order

- Sarah Davies, James Harris(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Yale University Press(Publisher)

Moreover, for much of the period, the cult of Stalin stood at the apex of a whole series of lesser cults focused on exceptional Soviet individuals ranging from leading Bolsheviks to film stars, record-breaking pilots, and Stakhanovite workers. Stalin himself rarely reflected publicly on his burgeoning cult, thereby appearing to distance himself from it. However in front of select audiences he did occasionally discuss the phenomenon. He continued to promote Plekhanov’s understanding of the role of the individual in history, and to voice criticisms of personality cults within the party, while at the same time justifying the persistence of ruler worship in the Soviet Union in terms of the “backwardness” of society. Stalin never deviated from the orthodox party line, which maintained that great individuals were only important insofar as they reflected wider social forces. This was the gist of his conversation with the German writer Emil Ludwig, which took place in December 1931 and was published the THE LEADER CULT 145 following year. Having rejected Ludwig’s comparison between Peter the Great and himself, Stalin proceeded to compare “his teacher” Lenin with Peter, describing the latter as a mere drop in the sea in relation to Lenin, who was the entire ocean. When Ludwig dared to suggest that he was contradicting the materialist understanding of history by acknowledging the role of outstanding individuals, Stalin countered with the argument that Marx did not deny the significance of heroic individuals—he simply maintained that they could operate only within a given set of conditions and that the great individuals were those who understood these conditions and how to change them. 48 Cults of party leaders were another matter altogether. Stalin occasionally expressed disquiet at the proliferation of mini cults of regional party leaders in the thirties. - eBook - PDF

The Invisible Shining

The Cult of Mátyás Rákosi in Stalinist Hungary, 19451956

- Balazs Apor(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Central European University Press(Publisher)

17 Introduction ritual practices that endorsed the cultic imagery of Communist notables. In addition, cults are often treated as singular phenomena by historians. They are normally analyzed in relation to a single leader, dictator, mon-arch, or emperor and are interpreted—in modern times at least—as the irrational side of personalized executive power. This preoccupation with a single leader is also reflected in the way the phenomenon was conceptu-alized in Bolshevik political rhetoric: the “cult of personality.”44 The term originated in the language of the Communist movement, and it entered popular parlance after Khrushchev’s famous revelations about Stalin at the Twentieth Congress of the CPSU in February 1956. It was also used extensively in postwar Kremlinology to highlight the nature of the Soviet leader’s rule.45 The analytical value of the notion has recently been criti-cized by a number of historians, although some of the alternative concepts suggested (“the cult of the number one”) seem equally imprecise, as they retain the focus on the individual leader.46 One of the main problems with the term—leaving aside the fact that very little was personal about the “cult of personality”—is that it has, for a long time, obscured important aspects of the phenomenon. Stalinist leader cults were not isolated phe-nomena; they formed an integrated, hierarchical system. Moreover, the systemic dimension of leader worship was not an accidental development: the cult was constructed as a system from the beginning. The worship of Stalin emerged in the framework of the twin cults of Lenin and Stalin, and while Stalin’s veneration overshadowed that of Lenin by the late 1930s, a number of lesser cults had developed by that time around members of Stalin’s inner circle.47 The Sovietization of Eastern Europe triggered the further extension of the Soviet ritual system to the countries under Communist rule. 44 The term “Bonapartism” was also used occasionally. - eBook - ePub

- Helena Goscilo(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

permanent attachment” (Oushakine 2000a: 1009, 1010). This provocative claim suggests that Soviet discourse, in essence, has become a post-Soviet fetish and that Russia’s civil society currently finds itself in a state of arrested development. Our examination of Putin mania leads us to a less gloomy conclusion. If we accept Oushakine’s premise that nations pass through life stages roughly equivalent to those experienced by individuals, we can understand both the Putin cult and the earlier personality cults it recalls in terms borrowed from Jacques Lacan’s theory of psychosexual development.As the most vivid example of a cult of personality, the Stalin cult indeed arrested the Soviet Union’s cultural development in what Lacan would call the mirror stage (Lacan 2006: 75–81). Much like the individual infant, whose ego is first constituted “through jubilant identification with its reflection, experienced as a powerful gestalt promising mastery, unity, and substantive stature,” Soviet society located its all-powerful, collective ego in the image of Stalin, the “father of all peoples,” “great architect of communism,” and “gardener of human happiness” (Muller and Richardson 1982: 6). In effect captivated in a dyadic relationship with the omnipotent image of Stalin, Soviet society failed to develop a symbolic register that would permit critique of the cult itself and, more importantly, the formation and expression of individual desire. In other words, Soviet cults of personality locked the country in an imaginary realm dominated by the leader’s image, which not only constituted national identity through a collective act of méconnaisance - eBook - PDF

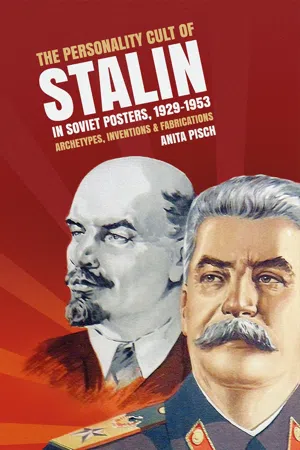

The Personality Cult of Stalin in Soviet Posters, 1929–1953: Archetypes, Inventions & Fabrications

Archetypes, inventions and fabrications

- Anita Pisch(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- ANU Press(Publisher)

Behrends, Polly Jones & E.A. Rees, The leader cult in communist dictatorships: Stalin and the Eastern Bloc , Hampshire, Palgrave, 2004, p. 33. 140 Istoriia Vsesoiuznoi Kommunisticheskoi partii (bolshevikov) Kratkii kurs , Moscow, Gospolitizdat, 1938. [History of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolshevik). Short Course.] 141 Davies, in Apor et al., The leader cult in communist dictatorships , p. 36. 142 I.V. Stalin, Sochineniia , 13, 1946–52, Moscow, Gospolitizdat, p. 19. 143 Davies cites numerous examples of Stalin’s detachment from his own cult, and of his apparent modesty (in Apor et al., The leader cult in communist dictatorships , pp. 29–30). 144 Davies, in Apor et al., The leader cult in communist dictatorships , p. 30. 145 Davies, in Apor et al., The leader cult in communist dictatorships , p. 38. 146 Plamper, The Stalin cult , p. 19. 147 Pioneer Leader, organ of the Komsomol Central Committee and the Central Council of the Pioneer Organisation. 115 2 . THE RISE OF THE STALIN PERSONALITY CULT Modesty and simplicity. Crystalline honesty and principled behavior in everything and always. Clarity of goals and toughness of character, overcoming all and every obstacle. Persistence and personal courage. These are the traits of character of great Stalin. These are the Bolshevik traits with which we should inoculate the Pioneers. 148 Largely due to the Marxist distaste for glorification of the individual, Lenin’s abhorrence of any kind of cultish behaviour, and to general Bolshevik asceticism, Stalin had to appear as if he was actively discouraging the excesses of the adulation directed at him, which was always to seem as if coming from below. 149 One useful mechanism for producing just such an effect was the Stalin Prize. The Stalin Prize was conceived in 1939 to coincide with Stalin’s 60th birthday celebrations and was first presented in 1941. - eBook - ePub

The Neo-Stalinist State

Class Ethnicity & Consensus in Soviet Society

- Victor Zaslavsky(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

It is widely accepted that the rebirth of the Stalin cult is due to the emotional attachment of the present leaders. In fact, many of today's leaders started their political careers during Stalin's time. He made Brezhnev a member of the Central Committee; it was in Kosygin's company that he was last seen in public; Gromyko, subsequently the minister of foreign affairs, was then a vice-minister; Epishev, subsequently the chief of the Central Political Directorate of the Armed Forces, was then in charge of the vice-ministry of state security; Ustinov, now defense minister, was then minister of armaments. The list could go on. It is well known, however, that gratitude to dead leaders is a rare quality among politicians and hardly influences the course of events. Many members of the group in power are indebted even more to Khrushchev, but this has not stopped them from prohibiting the mention of his name in the press even today. The current leaders' sympathy and approval of many of Stalin's policies have favored, but not determined, the rebirth of the ex-dictator's cult.What has happened becomes much more intelligible when seen within the context of the organization and the structure of power in the Soviet Union. Soviet society has been correctly described as a mono-organizational system.10 This fact is codified in the Constitution, which designates the CPSU as "the force directing and guiding society." This means that the party's bureaucratic apparatus, which has become one with state power, dominates society by organizing and directing the activity of otherwise totally atomized individuals. The party apparatus is in no way equal to the sum of individuals carrying out various tasks at any given moment. The apparatus consists of the totality of social roles, norms, relations, and laws, including the laws of self-reproduction and self-preservation. In turn, the functioning principle of this system — democratic centralism — inevitably leads to domination by the highest, "personified" echelon over the entire party apparatus.11The birth of the personality cult — through the concentration of power in the hands of a restricted number of people who choose the Leader and ascribe to him an artificial charisma — is the natural result of the operation of the single-party system. The Leader's personal qualities and good intentions do not change the situation. Despite Lenin's personal opposition, his cult was born and gained strength during the last years of his life, reaching its peak in the unprecedented decision to erect a mausoleum to preserve his embalmed remains. The history of the Stalin, Khrushchev, and Brezhnev cults shows how these mechanisms of cult manufacture work and are likely to develop. The apparatus's absolute power finds its most adequate embodiment in the Leader's personal power acting in the name of the apparatus and executing its will. - eBook - ePub

- Harold Shukman(Author)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

6Therefore, although many elements of the cult were irreparably damaged by developments between 1953 and the end of 1955, the full de-mythologisation of Stalin would require more than ignoring or sideswiping the late leader, and a more consistent approach to the totalitarian culture of the cult.7 Although the death of Stalin, and this early, limited confrontation of the Stalinist past had already rendered a return to Stalinism unlikely, it was still possible, before the 20th Congress, to look to Stalin and the Stalin era at least nostalgically, and often worshipfully. Indeed, such an attitude was seemingly encouraged by the continued saturation of public space with Stalin imagery (portraits, monuments), and the enduring dominance of ‘Stalin’ as totemic figure in the history books, and therefore within the historical narratives used in the education system—notably the Kratkii kurs (Short Course)— museums and public rituals.8 - eBook - ePub

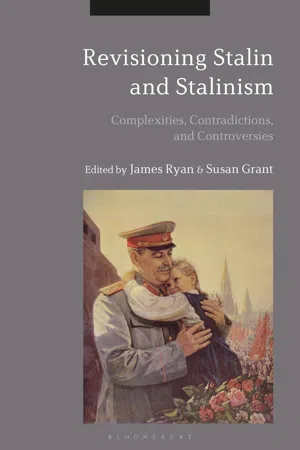

Revisioning Stalin and Stalinism

Complexities, Contradictions, and Controversies

- James Ryan, Susan Grant, James Ryan, Susan Grant(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Academic(Publisher)

The phenomenon spread across all cultural media. Journalism, academic writing, novels, poetry, painting, poster art, music, film, theatre, ceramics, textiles and so on bore witness to the cult. During the war, soldiers went on the offensive with the words ‘For Stalin’ on their lips. One poster said, ‘Thank You Stalin for a Happy Childhood’. Others reflected the supposed gratitude of workers and peasants for the benefits Stalin had brought them. In party posters the figure of Stalin moved from being a lesser acolyte of Lenin to becoming his equal and eventually the dominating figure. The trinity portrayals of Marx, Engels and Lenin soon became a quartet. The cult raises many issues beyond our scope here but it may be worth mentioning that Stalin himself did not appear to subscribe to it and on a number of famous occasions distanced himself from it. Of course, that may have been a subtle way of reinforcing it by portraying himself as too modest to go along with it. But maybe not. Perhaps it was simply a useful tool. It is also the case that the term ‘Stalinism’ was not part of the regular Soviet ideological vocabulary while Stalin was alive. His enemies, notably Trotsky, used the term in a disparaging sense from around 1936/7 but it was only after his death that the fount of ideological orthodoxy, The Institute of Marxism-Leninism, briefly became the Institute of Marxism-Leninism-Stalinism just as Khrushchev was about to denounce the cult of Stalin’s personality in his speech at the Twentieth Party Congress in February 1956. For the Stalinists there was no ‘Stalinism’, it was simply the orthodox version of Leninism.Where Stalin’s many supporters and admirers subscribed to the cult, in the capitalist and imperialist world a counter-cult reigned, which expressed itself in almost directly opposite language. The terms ‘dictator’, ‘monster’, ‘psychopath’, ‘power-hungry’, ‘cruel’, ‘brutal’, calculating’, ‘treacherous’, ‘talentless’, ‘ill-educated’, ‘deceptive’, ‘manipulative’, ‘byzantine’, ‘unintellectual’ flourished in a mirror-image version of the cult. Stalin was the source of all that was rotten in the Soviet Union. Where the cult followers saw his invincibility and infallibility, his Cold War critics saw evil personified. He was, it was frequently stated, an intellectual and social mediocrity, a psychological misfit marked out only by a lust for power, a deep sense of revenge and a barbaric streak of cruelty, often assumed to be the result of childhood beatings at the hands of his alcoholic father. Perhaps the only point the two versions of Stalin had in common was that he was a leading agent of history for good or ill. Ironically, both sides gave him a vast range of effectiveness and impact beyond any other force. Indeed, one of the points Stalin personally criticized about the cult was that it over-attributed influence to him as an individual, an approach he once claimed belonged to romantic, populist, hero-seeking thinking rather than the true Marxist acknowledgement of the role of deep historical forces beyond individual control.3 - eBook - ePub

- José Pedro Zúquete(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Within totalitarian movements, charismatic leadership is typically institutionalized through the personality cult (Flew and Yin, 2017: 8; Horn, 2011: 100). The figure of Joseph Stalin was a model and inspiration to Mao (Walder, 2015), linking the CCP-led revolution to others movements associated with Nazism, fascism, and communism. Like Stalin, Mao and others within the CCP movement sought to construct an ideology-based political religion which required the destruction of competing truths in order to place Mao’s leadership and exaggerated role at the center of both political and nonpolitical life, distinctions between which became blurred as the CCP gained power. This domination of social life through values, myths, rituals, and symbols intended to create an aura of sanctity around Mao. Thus, this cult of personality links back to systems of political myths which sought to motivate the masses through irrational and quasi-mystical thought, and which achieved great presence and intensity in other totalitarian countries prior to the 1940s (see Gentile, 2000). While the rituals of Maoism such as veneration of Mao’s portrait and writings, worship rituals, loyalty dances, and other demonstration of obedience appeared unique, they were linked to broader patterns of transnational political authority and, in particular, totalitarian systems of authority and legitimation which existed in other times and places.The cult of personality and manufacture of charisma through media as well as more immanent forms of leader-led relationships was, in the writings of anti-totalitarian theorists such as Hannah Arendt, a critical means by which totalitarian mass leaders, movements, and organizations engaged with people who had otherwise lost, often through war or economic depression, social identity and emotional bearings. Arendt’s analysis, in particular, is instructive for understanding how charismatic leadership functions within the broader totalitarian political system. Militancy resides at the core of all totalitarian movements (Baehr, 2017: 225–230). Though Weberian charismatic leadership may partly explain their power, authority created by charisma cannot ultimately be explained without equal reference to violence, as in the cases of Stalin and Adolf Hitler. Individuals must remain permanently dislocated through the perpetual motion of the movement. Purges, secret police, and new political formations distinct from existing organizational hierarchies (e.g., during the GPCR, Mao’s “Central Cultural Revolution Group”) exist to keep other political actors unbalanced and fearful. Emphasis on ideological correctness and the existence of unseen enemies further enhances the sense of vulnerability for all members of society. Within the totalitarian movement of Maoism and “struggle,” charismatic leadership existed as both engine of transformation and technique – buttressed by violence and supra-organizational systems of investigation and punishment – for engendering loyalty through the systematic elimination of competing standpoints. - eBook - PDF

The Nature of Stalin's Dictatorship

The Politburo 1928-1953

- E. A. Rees(Author)

- 2003(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

Short of the creation of another Stalin-type dictator, the only option available was a return to some system of collective leadership. In discussing the leadership system in this period, great care is needed in using the very term Politburo. Where decisions were taken by an inner group around Stalin, we can say no more than this. To talk of ‘de facto politburos’ simply muddies the water and whitewashes the real- ities of Stalin’s personal power. We need to avoid simplistic assumptions that dictatorship means individuals who rule in their own name, who rule exclusively without reference to any other institutions, or without reference to any ideological or belief system. Conclusion How we characterise the Stalin leadership must be considered apart from the question of the achievements of the Soviet system and the question of the degree of support it enjoyed among its people. Khrushchev was at pains to distinguish the achievements of the system from both the achievements and failing of Stalin as leader. While Stalin acquired despotic power he could never dispense with his subordinates. He needed them as assistants, advisers, counsellors, as foils in develop- ing policy initiatives, as accomplices, and for psychological support. Above all, he needed them as executives to run the great institutions. In their own spheres, they continued to exercise great power, and around these satellite leaders lesser cults were developed. Stalin always pur- ported to rule in the name of the party or the state, which was quite different from other systems of personal rule based on family, clan, ethnic, national or religious grouping. The collective provided him with 234 Stalin as Leader, 1937–1953 E. A. Rees 235 a degree of immunity, by spreading responsibility for policy. It was also a mechanism for controlling subordinates, who were not only his aides but also potentially his greatest rivals.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.