History

The Franks

The Franks were a Germanic tribe that played a significant role in the early medieval period, particularly in the formation of the Frankish Kingdom and the Carolingian Empire. Under the leadership of figures like Clovis I and Charlemagne, the Franks expanded their territory and exerted influence over much of Western Europe, leaving a lasting impact on the region's history and culture.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "The Franks"

- eBook - ePub

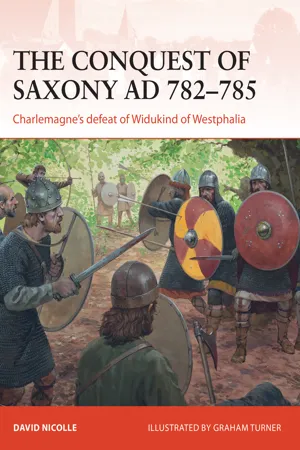

The Conquest of Saxony AD 782–785

Charlemagne's defeat of Widukind of Westphalia

- David Nicolle, Graham Turner(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Osprey Publishing(Publisher)

Apocalypse. (Ms. 31, Stadtbibliothek, Trier)Here it is important to understand that the identities of these medieval gens or peoples were not ‘ethnic’ in the modern sense. They were merely a form of self and group identification, which rarely expressed any real sense of superiority over other gens. Nor was there as yet any conclusive association between states under one ruling dynasty and the gens, of which there were often more than one, within that state. The concept of the nation-state had, of course, yet to impose itself upon the world.Each of the main Germanic peoples also had its own origin myths, partially reflecting its own traditions and partly invented by southern churchmen or scholars who sought to incorporate these mysterious newcomers into the world of Mediterranean history and legend. Thus The Franks first appear in written Roman historical records in the 3rd century AD as a confederation of Germanic tribes, living along the lower and middle Rhine River. Some of them raided Roman territory while others sought service with the Roman army as laeti or allies. By the mid-4th century AD one group, known to the Romans as the Salian Franks, had established a virtually autonomous ‘kingdom’ within the Roman frontier. As the Western Roman Empire collapsed in the 5th century AD , these Salians united under the Merovingian dynasty and conquered most of Gaul (France) as well as the ex-Roman provinces of Raetia, Germania Superior and part of Germania Magna.The Meuse (Maas) Valley near Dinant in southern Belgium. During the 8th century AD this area formed part of the military heartland of the Carolingian state. (Author’s photograph)A small Old Saxon silver brooch in the form of a horseman c. AD 500. (Historical Museum, Nienburg; author’s photograph)By the later 8th century AD The Franks were ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had succeeded the Merovingians in AD - eBook - PDF

- J. C. H. Blom, E. Lamberts, J. C. H. Blom, E. Lamberts(Authors)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- Berghahn Books(Publisher)

Little of their culture is known because Roman chroniclers themselves knew so little about them, and the bishop Gregory of Tours, author of the sixth century History of The Franks , did not have much to report about them, due to a dearth of writ-ten sources, a weak oral tradition, and Gregory’s own purpose, which concerned itself only with the ruling dynasty. Frankish warriors – in the tradition of many Germanic tribes – also chose to join the Roman army. Imperial policy, aimed at checking further Germanic migration, necessarily pitted Germans against Ger-mans as the once-mighty empire devolved into dictatorship, military rivalries, and civil war. The significance of The Franks does not rest, however, on their presence in the army – although some Frankish lead-ers attained high rank – but in their migration. By the mid-fourth cen-tury, Salian Franks were living in the Betuwe, between the Rhine and Waal, and later in Toxandria (the Campine), south of the Maas in Roman territory. Within the empire, they were recognized as foederati , federated with Rome, and in this position they absorbed Chamavi and Bructeri into their tribe. Frankish presence near the border, lasting sev-eral centuries, may explain their success in integrating so well into the Roman Empire. A certain amount of acculturation must have occurred, all the more after The Franks moved south and made Paris the center of their power. Saxons and Frisians Two other Germanic tribes, the Saxons and Frisians, also proved to be important to the history of the Low Countries. Both tribes hailed from northern Germany, and they, too, were sucked westward in the great migration. Much of their historical significance, of course, lies in their maritime role; Saxons and Angles, with Jutes and Frisians in their wake, established themselves in late Roman Britain. But their kinfolk also set-tled in the Low Countries. - Helmut Reimitz(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

For a long time, and even until now, many scholars have assumed that members of a Dark Age society rarely worried about such abstract ques- tions. As a result, modern historical scholarship largely took Frankish identity for granted.And yet, the Merovingian and Carolingian kingdoms have left us an impressive variety of meanings and interpretations for the name of The Franks. The Merovingian kings legitimated themselves as reges Francorum, but the name turns up as a description for particular regions or groups within the realms of these kings too. Merovingian and Carolingian historians continued the debates about the etymology of the name of The Franks that had already started in the time of the Roman Empire. 2 They also had different views on the origins of The Franks. In the various Frankish law books, the name of The Franks affirms that dif- ferent Franks in different regions claimed an elevated social and legal status in contrast to other social groupings, including new Franks. The name was used to legitimate the political claims of different elites and their position in the regnum. It was, however, also linked to Christian visions of community, to assert that a Christendom defined as Frankish took precedence over other Christendoms. 3 Some studies do indeed dis- cuss the ambiguity of the name of The Franks, which is documented in the extant sources, especially from the seventh century onwards. 4 This ambiguity, however, has rarely been explored as a sign of deeper reflec- tions about Frankish identity in the Merovingian and Carolingian king- doms. Most scholars seem to have trusted that The Franks themselves would have known who they were. We shall see in the course of this book that Merovingian and Carolingian contemporaries were not so sure.- eBook - PDF

- Alessandro Barbero, Allan Cameron(Authors)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

The Frankish Tradition THE SETTLEMENT OF The Franks IN GAUL Charlemagne is fi rmly identi fi ed in the European imagination with the title of emperor that was conferred on him at St. Peter’s on Christmas morning of 800. In reality, he only carried this title for the last fourteen years of his long life. Thirty-two years earlier he had become the king of The Franks, a title he kept even after gaining the imperial one, which, as we shall see, was intrinsically di ff erent and did not cancel out the king-ship he inherited from his father, Pepin the Short, in September 768. The poet who many years after his death was to write the Chanson de Roland would refer to him as “Carles li reis, nostre emperere magnes” and was clearly still well aware of this twin identity. 1 What did it mean to be king of The Franks toward the end of the eighth century? From the very beginning The Franks occupied an impor-tant position among the Germanic people who three or four centuries before Charles crossed the Rhine in small groups and settled there, fi rst as allies and then as overlords in the territory of the Roman Empire of the West. Strictly speaking, they were not even a people but a con-federation of tribes from the Rhine basin — Bructerii, Cattuarii, and Camavi — who spoke the same Germanic dialect, practiced the same 5 o n e religious cults, and followed the same warrior leaders. Thus they ended up adopting a collective name but one that initially constituted an ex-tremely weak form of identity. Originally Frank simply meant “coura-geous person” and later “free man.” Sidonius Apollinaris, a Roman, a Christian bishop, and a classical poet, describes The Franks he came to know in Gaul during the fi fth cen-tury. His words evoke a physical type that must have appeared decidedly exotic to a Mediterranean reader, but he did not hide his admiration for the courage of these barbarians: Their red hair falls from the top of their heads, while their necks are shaved at the back. - eBook - PDF

The Route of the Franks

The Journey of Archbishop Sigeric at the Twilight of the First Millennium AD

- Cristina Corsi(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Archaeopress Archaeology(Publisher)

Turned into allies of the Romans with the status of foederati, The Franks were not able to avoid the further infiltration of Germanic populations like the Vandals, Alans and Suevi (AD 406) (Destemberg 2017: 10-11). At the same time, other Germanic groups settled permanently in the frontier land that Caesar had established between Gallia and Germania, with the Burgundians, originally settled on the left bank of the Rhine (in the area of Worms), pushed by the Roman general Flavius Aetius in 443 into the region called Sapaudia (i.e. Savoy), from where they built the Romano- Barbarian kingdom of Burgundia. The latter lasted until 532/534, when it was incorporated into the rising Regnum Francorum by the successors of Clovis (Destemberg 2017: 14-15). Although it refers to a region whose borders shifted significantly over the course of time, the name of Burgundia, evolved into the French Bourgogne, still persists. The Franks With the progressive dissolution of Roman control, the Salian Franks occupied the regions of Tournai and Cambrai, between modern Belgium and the Netherlands, while the Ripuarian Franks expanded their domain to the area between the rivers Rhine, Meuse and Moselle, having as its capital the Roman town of Colonia (Köln) (see Figure 2.1) (Wallace-Hadrill 1982: 148-163). It was the leader of the Salian Franks, Clovis, son of Childeric I (the first acknowledged Merovingian king), who in the last twenty years of the fifth century started the process of unifying all of the Frankish tribes, imposing his authority on a multitude of chieftains. He also established the principle of inheritance of power to direct heirs, resulting in the creation of the first Merovingian royal dynasty. 1 After the battle 1 Two important contributions dedicated to Clovis and his time were published in 1997, the monograph by Renée Mussot-Goulard and the Chapter 2. - Rosamond McKitterick(Author)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- University of Notre Dame Press(Publisher)

63 T H R E E The Franks and Their History In the previous two chapters I have examined perceptions of the past re-flected in a range of historical writing, both that written in late antiquity and dis-seminated within the Carolingian empire and that composed by The Franks themselves. This historical writing maintains the concept of the historical and chronological map and the laying out of a mosaic of historical knowledge on the Eusebius-Jerome model. Yet what the chronicler of 741 , Ado of Vienne, and Regino of Prüm constructed from their range of sources is of an entirely different character from that in earlier “universal histories.” The contrast revolves, first of all, on the presentation of Rome nourished by their choice of sources, in which the Liber Pontificalis and historical martyrologies are of central importance. In the preceding chapter, therefore, I examined the perception of Rome and the Roman past in the Frankish world of the eighth and ninth centuries in greater detail. I highlighted the way in which the intertwining of Roman sacred and Roman secu-lar and imperial history echoes the emphasis of the Carolingian texts. Even the sylloges, itineraries, and martyrologies reflect a perception of Rome as important 64 P e rc e p t i o n s o f t h e Pa s t i n t h e E a r ly M i d d l e Ag e s for both Christian and imperial history. The imperatives of the emulation of Rome, the religious function of ancient Rome, and the Christian memory of Rome in the Carolingian sources are very striking. In offering an interpretation of Arn of Salzburg’s handbook on Rome in the Vienna, ÖNB, lat. 795 , codex, as well as of the individual presentations of Rome in Frankish narrative sources, I stressed tex-tual knowledge. But I also emphasized the crucial role played by the physical and material relics of the past, whether buildings or bones of saints, in Frankish per-ceptions of the past.- eBook - PDF

- (Author)

- 0(Publication Date)

- Rough Guides(Publisher)

HISTORY CONTEXTS 857 804–76 A distinct German language and literature emerge under Frankish king Louis the German 962 The Pope crowns Otto the Great king of Germany and emperor of the Holy Roman Empire as the Saxon ruler cements Germany as a kingdom 1152–90 As Frederick I – Frederick “Redbeard” – focuses on Italy, central authority collapses slowly into princely states Africa. The Ostrogoths moved from the Black Sea to today’s Hungary, then Italy, while the Burgundians moved from northern Germany through the southwest of the country and finally to southeastern France – as celebrated in the Nibelungenlied (see box, p.527). Successor states The overstretched Roman Empire was forced to compromise to resolve most territorial questions in Europe, and it consented to Germanic successor states such as the Visigothic and Burgundian kingdoms. Meanwhile, The Franks, Frisians, Saxons, Thuringians, Alemanni and Bavarians emerged, all the product of smaller tribes clubbing together to defend themselves against the Huns. As the western Roman Empire crumbled they integrated the Roman provincial population into their own, fusing a Germanic military with Roman administrative skills that would establish taxes and legal powers for these German rulers. The Franks Among these new Germanic tribes, The Franks proved themselves the strongest. From their fifth-century tribal lands in today’s Belgium, they began to expand south and east, particularly under King Clovis (482–511) of the Merovingian dynasty. In 751 the Carolingian dynasty took over and continued to expand under their greatest leader, Charlemagne (768–814), who made Aachen – now Germany’s westernmost city – his capital. At the time of his death the Frankish empire took up most of modern-day France, Germany and northern Italy. - eBook - PDF

Neglected Heroes

Leadership and War in the Early Medieval Period

- Terry L. Gore(Author)

- 1995(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

THE FRANKISH POLITICAL AND MILITARY SITUATION IN THE EIGHTH CENTURY Western European leaders had fought among themselves continually since the last vestiges of Roman order had dissolved. Though the religious philosophers of the sixth century on attempted to impose order on a society left adrift, they lacked a focus upon which to direct the aggressiveness of the western military rulers. War had become a prevalent and ubiquitous activity as Philippe Contamine notes: The omnipresence of war is equally revealed in the Germanic names which became popular in Gaul among the descendants of the Gallo-Romans in the 7th century: Baudry (Bald-Rik: bold-powerful); Armand (Heri-man: man of war); Roger (Hrot-gar: glori- ous spear); William (Wile-helm: will-helmet); Gerard (Ger-hard: strong lance); Louis (Chlodo-wed, Hlodovicus: famous warrior).2 The Germans dominated Gaul, much as they had Britain, and converted to Chris- tianity, giving up, as Sir E. S. Creasy wrote, “[m]uch of the coarse ferocity which must have been fostered in the spirits of the ancient warriors of the North by a mythology which promised, as the reward of the brave on earth, an eternal cycle of fighting and drunkenness in heaven.”3 Einhard wrote, “The Saxons, like almost all the peoples living in Germany are ferocious by nature.”4 Order could not easily be imposed on these fragmented, warring factions. Groups of families lived together on a constant war footing. Contamine noted that “[e]ach individual, every social or family group, had to look to their own security, to de- fend their rights and interest by arms ... [which] became a habit among the whole population.”5 The Christian churches became repositories of wealth, while powerful warlords emerged from the chaos and weaker neighbors became dependent on them for their own survival. Slowly, dynastic houses arose as the most powerful leaders attracted followers willing to swear allegiance out of fear and the need for protec- tion. - eBook - PDF

- Jinty Nelson(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Hambledon Continuum(Publisher)

10 Rewriting the History of The Franks The past is another country: but each generation perceives its otherness in different terms, for itself. 1 Just as geographers of the 1980s want new maps that show features not thought significant by previous mapmakers, so every generation of historians needs new textbooks; and the job of the publishing profession is to supply them. But in this country, over the past thirty years or so, the needs of students of Prankish history have not been supplied: instead they have had to find their way in difficult terrain with the help of, for the most part, some fairly elderly guides. In 1980 J.M. Wallace-Hadrill's The Barbarian West, first published in 1952, offered, still, the best route into Prankish territory; and the intrepid Carolingianist had to rely on Louis Halphen's Charlemagne et l'empire carolingien, published in 1947. 2 The work of these scholars and their contemporaries on the early middle ages was also, inevitably, a response to the history of Europe in the first four-and-a-half decades of the twentieth century. For them, unlike historians whose main interest lay in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, pessimism came easily. Their pitch began with the fall of one great empire and ended with the fall of another. Only a determined optimist willing to penetrate the iron heart of the tenth century, and to go beyond it to the twelfth, could write of'the crumbling of the Carolingian Empire' resulting in 'the birth of Europe'. 3 For most scholars, what gave unity to the early medieval centuries was the epic theme of doomed resistence to inevitable decay. Thus Wallace-Hadrill closed his book with an evocation of the mentality of the late tenth century: 'The apocalyptic outlook of Gregory the Great was not dead. - eBook - PDF

- Graeme Small(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Red Globe Press(Publisher)

The kingdom over which these powers were exercised may now be considered in greater detail. RULING THE FRENCH IN THE LATE MIDDLE AGES 35 Regnum Franciae As late as the thirteenth century the kingdom was still referred to as Francia , a term that appeared in the early Middle Ages and could mean where The Franks lived generally, or a particular centre of Frankish power, the Parisian region. The use of the term Regnum Fran-ciae , Kingdom of France, is first recorded in 1205, and by the start of our period it had become the norm in documents issued by the royal chancellerie . In the course of the thirteenth century the king him-self became Rex Franciae , ‘King of France’, rather than Rex francorum , ‘King of The Franks’. The first detailed description of the kingdom was written by Gilles le Bouvier, usually known by his official title of Berry herald, in the context of his Livre de la description des pays (Book of the description of lands, c. 1450). There we learn that the realm extended from Sluis in Flanders in the north to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port in the Pyrenees in the south; from Lyon in the east to Finistère in Brittany in the west. It was ‘closed’ by natural boundaries on all sides save the east, where Le Bouvier described a looser frontier of four rivers: the Rhône, the Saône and the Meuse, thence one day’s journey to the Escaut in the Cambrésis, and down that great river to the Channel. These were effectively the frontiers created by the Treaty of Verdun in 843 to fashion the West Frankish kingdom of Charles the Bald from the Carolingian Empire. There were other boundaries which Le Bouvier might have men-tioned, but only one of them entered his account – that attributed to Gaul, incorporating lands now in the Empire, but ‘which used to belong to the Kingdom of France, and where they speak French coarsely’. - eBook - ePub

The Barbarian West, A.D. 400-1000

The Early Middle Ages [1952 ed.]

- J M Wallace-Hadrill(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Barakaldo Books(Publisher)

Lex Salica is, or represents, the unalterable code by which all Franks lived all the time. It simply gives us a valuable general idea of how they lived at one particular time.The sons of Clovis ruled independently over their shares of partitioned Gaul from the cities of Metz, Orléans, Paris and Soissons. But they had also inherited from their father a religion and a view of the non-Frankish world that caused them from time to time to act as one. They agreed to give their sister in marriage to Amalaric, the Visigoth king of Spain, and sent her off with ‘a heap of fine ornaments’, as befitted a barbarian princess. Soon, however, they found it necessary to rescue her from the Arians, and brought her back with even more ornaments. They agreed also upon an expedition against the Burgundians, which resulted in the political extinction of that once powerful people, and in the extension of Frankish power over Provence, and notably over a great Mediterranean port, Marseilles. We may explain such unprovoked aggression in a number of ways; by fear, by tribal hatred, by vendetta, or by the always urgent need for plunder to reward followers, and for slaves. Each year in the springtime The Franks set out in their war-bands upon some such venture; for fighting was as much the business of good, as carousing was of foul weather.{14}The chieftain who ruled in Metz over the Eastern, or Austrasian, Frankish settlements faced greater dangers than did his brothers. From the banks of the Rhine he kept watch upon an arc of disturbed and hungry people who were beginning to feel Slav pressure behind them. These were the Danes, Saxons, Thuringians and Bavarians. Fighting them and keeping them at bay, Theuderic and his son Theudebert (modern French Thierry and Thibert) earned a name that lived on in Germanic epic, and established the right of The Franks to watch over the movements of tribes in the heart of Germany, to intervene forcibly in tribal vendettas, and to exact, when they could, heavy tribute of livestock and slaves. - eBook - PDF

- Johannes Fried, Peter Lewis(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Harvard University Press(Publisher)

The capitulary of Didenhofen from the year 805 makes it clear that trade was going on in the vicinity of the frontier with the Slavs and Avars. In these legislative acts, the emperor decreed that Frankish mer-chants were not permitted to venture farther than Bardovic, a site called Schezla (no longer identifiable), Magdeburg, Erfurt, Hallstadt (a remote lo-cation near Bamberg in Franconia), Forchheim, Pfreimt (near the town of Nabburg in the Upper Palatinate), Regensburg, and Lorch (on the river Enns in Upper Austria). Furthermore, they were not allowed to sell weapons or coats of mail. 52 The ban on trading in weapons hints at the existence of a Slavic upper class who wanted to emulate The Franks. In return, though, these Slavic noblemen could well have traded in unbaptized slaves from among their own people. No Frankish trader ever strayed among the Danes; this people remained a mystery. Indeed, as a general rule, only very sparse information from the Scandinavian world reached the Frankish royal court either before or during Charlemagne’s reign. Likewise, empires began to form and peoples to co-alesce only during the era of the Frankish emperors, initially among the Danes and the Svea—the people for whom the future state of Sweden was named 53 —around Lake Mäleren. Despite carving occasional runic inscrip-tions, these peoples were all illiterate, nurturing instead the practice of oral transmission of history in a highly sophisticated bardic tradition that only partially (and even then with the content much altered) found its way into later written histories. 54 Scandinavia’s many islands and heavily indented coastline predisposed its peoples to seafaring from a very early period, but the seagoing capability of their longships, the range of their voyages, and the audacity of their explorations remained hidden to their neighbors, in-cluding The Franks, for a very long time.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.