History

The Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg Trials were a series of military tribunals held after World War II to prosecute prominent leaders of Nazi Germany for war crimes. The trials established the principle that individuals can be held accountable for committing atrocities during wartime, regardless of their official status. The proceedings set a precedent for international law and the prosecution of individuals for crimes against humanity.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "The Nuremberg Trials"

- eBook - PDF

- Eirik Bjorge, Cameron Miles, Eirik Bjorge, Cameron Miles(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Hart Publishing(Publisher)

154 Those words, written 70 years ago, are no less true today. Nuremberg was, from a legal perspective at least, a moment of crystallisation following a period of unspeak-able horrors. In the context of the early plans for summary executions, it was nota-ble that the Nuremberg trial occurred at all. Courtroom 600 is rightly regarded as the birthplace of the modern system of international criminal justice: the conception of a novel (if not entirely unprecedented) kind of international court, a fresh legal jurisdiction, and a new way of holding to account some of those responsible for atrocities against both individuals and groups, albeit in a way that was lopsided and left unpunished certain other crimes—including those committed by the Allies. Nuremberg reflects the marriage of pragmatism and principle. It has not altered the reality of war and law; attempts to deliver post-conflict justice remain flawed, insufficient and uneven. What Nuremberg did achieve was to set a framework or expectation that the consequences of conflict could be dealt with in a particular way, according to what are now recognised as fundamental international principles. Those principles have been deployed time and again, and have developed in ways that were not anticipated at the time of their conception. The example set by Nuremberg would stand alone for 50 years before bearing fruit, but would ultimately be taken up in successor tribunals of various forms. The tribunals for the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Cambodia and Lebanon have drawn on the Nuremberg model in crafting hybrid jurisdic-tional arrangements. 155 In July 1998, more than 150 states adopted the Statute for an International Criminal Court. These tribunals have indicted, convicted and 152 Prosecutor v Kambanda , Judgment and Sentence (ICTR-97-23-S), 4 September 1998, [16]. - eBook - PDF

Global Justice

The Politics of War Crimes Trials

- Kingsley Chiedu Moghalu(Author)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

“No conceivable evil,” wrote a contempo- rary historian, “was beyond him.” 40 The defense of superior orders argued by the defendant did not avail him, and a court of twenty-eight judges found von Hagenbach guilty and sentenced him to death. But it was certainly the precedent of The Nuremberg Trials that captured the world’s imagination and established international war crimes justice as policy and strategy. Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in Germany in 1933 provided the vehicle for his pursuit of expansionist dreams, inspired by theories of racial superiority, which culminated in World War II. Beginning inside Germany and continuing outward through aggression and conquest in Europe, it is estimated that 30 million people were killed during the 12 years of Hitler’s dictatorship—on the battlefields of his wars, in forced labor camps, and in gas chambers. 41 Violations of the human rights of minorities and crimes against human- ity were transparently part of the official policies of Hitler’s Nazi govern- ment. Widespread outrage at the atrocities of the Nazi regime among Allied nations that united to repel the aggression by Hitler and other Axis Powers led to a determination to punish the Nazi leaders at the end of the war. Thus was the International Military Tribunal (IMT) at Nuremberg established in 1945 to try the political leadership and officer corps of the German gov- ernment and military high command. 42 The four Allied Powers appointed the tribunal’s judges, one from each country (with each backed up by an alternate). The United States appointed Francis Biddle, a former attorney 28 Global Justice general of the country whom President Harry Truman had dismissed in an act of political vengeance but now wanted to placate. 43 France appointed Henri Donnediue de Vabres, a scholar of international law and a former law professor at the University of Paris who was one of the early visionaries of a permanent international criminal court. - eBook - PDF

International Criminal Tribunals

Justice and Politics

- Y. Beigbeder(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

The American Nuremberg trials Control Council Law No. 10 on the ‘Punishment of Persons guilty of war crimes, crimes against peace and crimes against humanity’ of 20 December 1945 37 created the framework for trials of German military and civilian personnel other than those dealt with by the International Military Tribunal, by establishing a uniform legal basis for their pros- ecution. The Moscow Declaration of 30 October 1943 and the London Agreement of 8 August 1945 were made integral parts of this Law. The Allied Control Council was composed of the commanders of the four zones of occupation in post-war Germany. In implementation of this Law, the US military government issued Ordinance No. 7 of 25 October 1946 that provided for three-judge courts. Six such courts, composed of US attorneys, were established at Nuremberg. They heard a total of 12 cases between 1946 and 1948, all but one involving multiple defendants. The cases concerned medical experiments on inmates in concentration or exterminations camps, 34 International Criminal Tribunals judicial murders and other atrocities, SS Units charged with the mur- der of specific groups in conquered areas of the USSR (Einsatzgruppen), industrialists and financiers to the Nazi Party, and military cases. The courts indicted 185 defendants – out of those who stood trial, 35 were acquitted, 24 sentenced to death and others received prison sentences. 38 The trials were important in establishing (or confirming) the interna- tional responsibilities of such white-collar perpetrators as industrialists and business leaders and medical doctors. However, the International Military Tribunal remains the principal historical and judiciary founda- tion for Nuremberg Law. Conclusion Nuremberg had its warts, which have been noted above: victors’ jus- tice, the application of ex post facto legislation and the tu quoque argu- ments. Donnedieu de Vabres 39 aptly summarized the value of the trial and some of its weaknesses. - eBook - PDF

- Joan Wallach Scott(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Central European University Press(Publisher)

Acting “in the name of History,” the European powers offered themselves as the embodiment and future guardians of “civilization.” In this chapter, I focus on the first Nuremberg tri-al held by the International Military Tribunal (IMT), the judicial inquiry that began in 1946 into the ac-tions of twenty-four former top Nazi officials and six organizations. The trial was meant to expose the un-precedented evils of Nazism and so to confine them to the past from which they had come and where they rightly belonged. It sought to secure the memory of evil deeds as a way of forever banishing them. Con-victing the perpetrators, the US prosecutor promised, would permanently render their “sinister influenc-es” politically and morally unacceptable. “Civiliza-tion can afford no compromise with the social forces which would gain renewed strength if we deal ambig-uously or indecisively with the men in whom those forces now precariously survive.” 1 The Nuremberg Trials “for the first time called his-tory itself into a court of justice.” So argues Shoshana Felman in an essay on Walter Benjamin. At Nurem-berg, history itself was on trial she writes. “The func-tion of the trials was to repair judicially not only pri- 9 vate but also collective historical injustices.” 2 The judgment rendered would bring the revelation of the “meaning of history,” (that is, the meaning of the past) forcing it to “take stock of its own flagrant injustices.” 3 History, in this view, was not the subject but the ob-ject of judgment at Nuremberg. The death sentenc-es handed down were meant symbolically to con-firm that justice had been delivered (evil recognized as such and eliminated), even if no ultimate compen-sation were possible for the crimes that had been com-mitted nor any guarantee established that their under-lying causes had been eradicated. The trial judges saw as their task the protection of the future from the pernicious influences of the past. - eBook - PDF

Judging War Criminals

The Politics of International Justice

- Y. Beigbeder(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

2 The Nuremberg Precedent For the first time in history, after World War II, an international tribunal judged and sentenced high-level politicians and senior military officers for their responsibilities, or their consenting part, in the commitment of crimes against peace, war crimes and crimes against humanity. The creation of this tribunal, its Charter and its judgments, have extended the traditional scope of international humanitarian law, in adding international criminal law and justice to the laws of Geneva and the Hague. This significant innovation was made possible by the revelations of systematic mass atrocities committed by the Nazis before and during the war, which created both horror and an urge for revenge and punishment, and by the leadership of the USA in having its war allies agree to a judiciary process, rather than summary execu- tions of those major war criminals detained by them. The failure of an effective judiciary process for alleged war criminals after World War I was another factor in the creation of the Nuremberg tribunal. THE TREATY OF VERSAILLES AND THE LEIPZIG TRIALS The violation of the neutrality of Belgium and Luxemburg by the German army in August 1914, the misery of refugees fleeing from occupied countries, pillage and destruction of cities, the sinking of the Lusitania and the use of poison gas during the battle of Ypres had aroused outrage and calls for revenge and punishment mainly from British and French public opinion, even though some of the accusations of indiscriminate murder, rape and infanticide were later shown to be the product of war propaganda. Charges were levelled against the Kaiser and other alleged war criminals. The Paris Peace Conference, which started on 18 January 1919, established a Commission on the Responsibility of the Authors of the War and the Enforcement of Penalties. 1 The Commission's report submitted in March 1919 charged Germany and her allies with 27 - eBook - PDF

Nazi Law

From Nuremberg to Nuremberg

- John J. Michalczyk(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Academic(Publisher)

Churchill proposed an outright execution of the Nazi leadership while Stalin initially urged the execution of 50,000–100,000 German staff offi cers. Later he agreed upon a trial, but in his mind, it would be a show trial like the 1930s Soviet mock trials where the defendant was convicted prior to the trial. Reason prevailed, thanks to the Americans. The four Allied powers, the United States, England, France, and the Soviet Union, met in London on August 8, 1945 to decide upon the prosecution of the Nazi war criminals and signed the London Agreement. It became the foundation for establishing the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, and Chief Justice Robert H. Jackson led the US team at Nuremberg in November 1945 in a democratic process whereby those charged with criminal activities had their day in court with legitimate defense 220 Nazi Law attorneys. The conspiracy charges brought against the high-ranking offi cials included war crimes, crimes against peace, and crimes against humanity. In addition to the principal Nuremberg Trial that the four Allies organized, the International Military Tribunal, there were twelve subsequent Nuremberg Trials that were conducted by the Americans in that zone, including the more well-known Physicians’ Doctors’ Trial (December 9, 1946 to August 20, 1947). One of the trials the Americans also held there was the juror’s trial (March 5 to December 4, 1947), a trial of sixteen judges and attorneys who were charged with creating a plan to establish racial purity throughout Germany through racial policies as in the Nuremberg Laws and eugenics principles. This was a critical trial because it focused on the recommitment to law following the manipulation and abuse of the legal system since 1933. - eBook - PDF

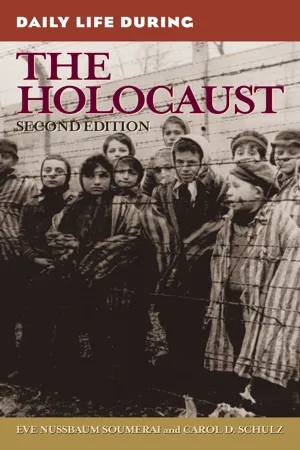

- Eve Nussbaum Soumerai, Carol D. Schulz(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

Hundreds of scientists, including war criminals, were brought to the United States to work for the military and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration—just as Jewish refugees such as Alfred Einstein had done prior to the war. Thousands of others who partici- pated in the “crimes against humanity” were never tried. WHAT WAS ACCOMPLISHED BY THE TRIALS? For the very first time in history, individuals were held responsible for their particular crimes against humanity. Swearing allegiance, taking an oath, or taking orders were no longer acceptable reasons for their defense. Also, the masses of German recorded evidence presented at the tribunal will make it almost impossible for present and future revisionist histori- ans to claim that these crimes did not occur or were exaggerated— almost impossible, because there are always those who try to distort or deny the evidence. In the continuing struggle for freedom from persecution and unbridled hate, The Nuremberg Trials played a significant role and as such must be remembered. POSTSCRIPT Adolf Hitler, the chief defendant, was absent. On the night of April 28, 1945, he had married his faithful mistress Eva Braun. Shortly before 4:00 a.m., on April 29, he called in his secretary and dictated the final sentence of his political testament: “Above all I obligate the leaders of the nation and their following to a strict observance of the racial laws, and to a merciless resistance to the poisoners of all peoples, interna- tional Jewry.” Eliminating Jewry was his passion (Trevor-Roper 1947, 280 Daily Life During the Holocaust 179); dominating all of Europe, his goal. Had they obeyed his decree, what would have happened to morality? The next day, April 30, 1945, between 2:00 and 3:00 p.m., Hitler put his Walther pistol against his right temple, bit into a cyanide capsule, and pulled the trigger. WORKS CITED Conot, Robert E. Justice at Nuremberg. New York: Harper and Row, 1983. - eBook - PDF

- Douglas Irvin-Erickson(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- University of Pennsylvania Press(Publisher)

urged the president to ensure that postwar justice avenged Nazi crimes against the Jews. However, as Philip Spencer notes, it eventually became obvious that trying Nazi leaders for humanitarian crimes would cause political problems for the Allies. 4 Popular memory often holds that the Nuremberg tribunal was intended to bring legal justice for the horrors of the Jewish Holocaust, even though Nuremburg 139 the tribunal eventually rejected the principle of trying Nazi leaders for their crimes against the Jews. 5 For many scholars and activists, The Nuremberg Trials are often considered legalism’s greatest victory in securing human rights. Yet, here again, in the words of Gary Bass, “it is only in retrospect that Nuremberg has become unimpeachable.” 6 Although it is tempting to see the trials as predetermined, at the time it was not obvious to the Allies that they should not simply execute the defeated and move on with rebuild-ing. 7 Stalin proposed dealing with the matter of justice by shooting fifty thousand Germans. Churchill proposed that the leaders of the Nazi regime be executed without trial. As the support for trials began to take shape, Stalin eventually shifted positions and pressured the allies to turn the tribu-nal into a show trial so there would be no possibility of embarrassing acquittals. 8 And, it should be remembered, Morgenthau, Jr. had convinced Roosevelt to “pastoralize” Germany—by de-industrializing the economy, executing German officers, and banishing all SS officers to far-off places of the world. Morgenthau, Jr. cited the Ottoman deportation of Greeks that his father had witnessed as ambassador to the Ottoman Empire as legal precedent. 9 It was a strange precedent, given that Morgenthau, Sr. - eBook - PDF

The Politics of International Criminal Justice

German Perspectives from Nuremberg to The Hague

- Ronen Steinke(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Hart Publishing(Publisher)

22 If Nazi war criminals were to be punished without trial, ‘Germany will simply have lost another war’, argued Murray Bernays, one of the propo-nents of Nuremberg within the US government, in September 1944. ‘The German people will not know the barbarians they have supported, nor will they have any understanding of the criminal character of their con-duct and the world’s judgement upon it.’ 23 The advantage of clarifying ‘historical truth’ was thus one which appealed to power politicians especially. 24 In a June 1945 memorandum to Robert Jackson, Telford Taylor described what he considered to be the ‘most important’ goal of these trials besides demonstrating Allied unity after the war: To give meaning to the war against Germany. To validate the casualties we have suffered and the destruction and casualties we have caused. To . . . make the war meaningful and valid for the people of the Allied Nations and, it is not beyond hope, for at least some people of the Axis Nations. 25 19 ibid 196. 20 ibid 180. 21 ibid 202. 22 Bradley F Smith, The American Road to Nuremberg (Stanford, Hoover Institution Press, 1982) 23. 23 Memorandum by Murray Bernays, Colonel in the US War Department, ‘Trial of European War Criminals’ (15 September 1944). Quoted in ibid 26. 24 This point is somewhat missed by Paul Betts, ‘Germany, International Justice and the Twentieth Century’ (2005) 17 History & Memory who notes at 59: ‘the Americans . . . and cer-tain key figures within the British Foreign Office convinced their allies about the virtues of avoiding vengeful retribution, and that trying Nazi leaders was the most fair way to dis-pense lasting justice’. 25 Compare Taylor, The Anatomy of The Nuremberg Trials (n 2), 50. 44 German Objections to The Nuremberg Trials after 1949 Selecting Illustrative Defendants In the trial of major war criminals, the 24 accused were carefully selected to represent the different parts of Germany’s elite made responsible for the Nazi regime’s crimes. - Devin O. Pendas(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

2 This is most obvious in the case of Benjamin Ferencz, a former Nuremberg prosecutor and later a major advocate for the creation of a permanent International Criminal Court. See e.g. Benjamin B. Ferencz, An International Criminal Court: A Step toward World Peace – A Documentary History and Analysis (Dobbs Ferry, NY: Oceana Publications, 1980). For other examples, see Introduction, note 1. 3 Sikkink, The Justice Cascade, p. 5. 4 Robertson, Crimes against Humanity, p. xvii. 5 See e.g. Donald Bloxham, Genocide on Trial: War Crimes Trials and the Formation of Holocaust History and Memory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001); Minow, Between Vengeance and Forgiveness; or Stephan Landsman, Crimes of the Holocaust: The Law Confronts the Hard Cases (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005). 23 the Allied war crimes trial program more generally, foster political tran- sition in Germany after the Second World War? It is the contention of this chapter that, for the most part, it did not. If criminal prosecution for Nazi crimes played a significant role in the political transformation of Germany after the Second World War, it was not the Allied trials but their rather more obscure German counterparts that effected this change. Before analyzing the role of domestic prosecutions in transitional justice in postwar Germany, it is necessary to first determine what the Allies hoped to achieve with their own trials and whether they succeeded. 1 Allied Goals for the International Military Tribunal As historian Richard Bessel has recently remarked, Germany in the Second World War had the dubious distinction of having attained some- thing quite rare in world history – total defeat. 6 As a consequence, the fate of Germany in the immediate postwar years lay largely in the hands of the occupying Allies.- eBook - PDF

Understanding Transitional Justice

A Struggle for Peace, Reconciliation, and Rebuilding

- Giada Girelli(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

CHAPTER 6 The Origins of International Criminal Accountability: The Nuremberg and Tokyo Tribunals INTRODUCTION On the morning of November 20, 1945, 1 curtains rose on one of the most innovative and awaited legal events in modern history: the International Military Tribunal (IMT) set up in the German city of Nuremberg to pronounce on the responsibilities of some among the most renowned figures of the fallen Nazi regime – the first tribunal successfully created to deal, supranationally, with mass atrocities. 2 A few months later, the operations began of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), better known as the Tokyo Tribunal, responsible for judging representatives of the Japanese military and political élite for the events that unfolded during World War II. 3 One will become the archetype of international criminal justice, while the other sunk into oblivion, as little more than a façade installed by the Americans to sanctify their victories in the region while shifting the conversation away from the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. 4 The two bodies will be discussed here jointly, as together they consti- tute a first phase in the development of the model of individual criminal accountability at the supranational level, for acts that will be identified as the worst menaces and insults to a shared humanity. After a brief recon- struction of the negotiation processes that led to the creation of the two bodies, and an overview of the key features of the statutes of the courts, attention will be devoted to some dilemmas emerging in many debates © The Author(s) 2017 G. Girelli, Understanding Transitional Justice, Philosophy, Public Policy, and Transnational Law, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-53606-4_6 125 - eBook - PDF

- Robert Cryer(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

3 1945 Nuremberg International Military Tribunal Statute; 1945 Nuremberg International Military Tribunal Rules of Procedure and Evidence and 1945 Control Council Law No. 10 3 1945 Charter of the International Military Tribunal (Nuremberg) I. CONSTITUTION OF THE INTERNATIONAL MILITARY TRIBUNAL Article 1 In pursuance of the Agreement signed on the 8th day of August 1945 by the Government of the United States of America, the Provisional Government of the French Republic, the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, there shall be established an International Military Tribunal (hereinafter called “the Tribunal”) for the just and prompt trial and punishment of the major war criminals of the European Axis. Article 2 The Tribunal shall consist of four members, each with an alternate. One member and one alternate shall be appointed by each of the Signatories. The alternates shall, so far as they are able, be present at all sessions of the Tribunal. In case of illness of any member of the Tribunal or his incapacity for some other reason to fulfill his functions, his alternate shall take his place. Article 3 Neither the Tribunal, its members nor their alternates can be challenged by the prosecu- tion, or by the Defendants or their Counsel. Each Signatory may replace its members of the Tribunal or his alternate for reasons of health or for other good reasons, except that no replacement may take place during a Trial, other than by an alternate. Article 4 (a) The presence of all four members of the Tribunal or the alternate for any absent member shall be necessary to constitute the quorum. (b) The members of the Tribunal shall, before any trial begins, agree among themselves upon the selection from their number of a President, and the President shall hold office during the trial, or as may otherwise be agreed by a vote of not less than three members.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.