Politics & International Relations

Scottish Parliament

The Scottish Parliament is the devolved, unicameral legislature of Scotland, with powers over areas such as education, health, and justice. It was established in 1999 following a referendum, and its members are elected through a mixed-member proportional representation system. The Parliament has the authority to make laws on a range of issues affecting Scotland, while certain powers remain reserved to the UK Parliament.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Scottish Parliament"

- eBook - ePub

- Guy Laforest, André Lecours(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- McGill-Queen's University Press(Publisher)

The achievement of the Scottish Parliament, however, has been to become a local version of Westminster, or other European parliaments, rather than a new type of body. The small size of the country and the spirit of devolution make it more accessible than Westminster, a finding confirmed by research among Scottish interest and advocacy groups. 27 Actors like the business community, who initially thought to bypass it because of their strong links into London, have been obliged to play the Scottish political game; 28 but this has not fundamentally altered the balance of power between the executive and the legislature. NOTES 1 This was the case of McCormick vs the Lord Advocate, concerning the use of the title Queen Elizabeth II in Scotland, when neither Scotland nor Great Britain had had an Elizabeth I. 2 Since 1800 the state is the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (since 1922 Northern Ireland). It is correct to distinguish this wider United Kingdom (UK) from Great Britain. 3 Tony Blair, as his memoirs show, was no home ruler but was given no choice. 4 Around 1983 I had advised Labour’s devolution committee that the new body should be called a parliament, that it should be elected by proportional representation, that the reserved and not the devolved powers should be specified, and that the European Convention on Human Rights should be incorporated in the legislation. All four suggestions were rejected at the time but eventually featured in the 1998 Scotland Act. 5 Constitutional legislation is by convention taken on the floor of the House of Commons and there is an emerging convention that major changes in devolution or electoral systems will be subject to referendum - Stephen Weatherill, Ulf Bernitz, Stephen Weatherill, Ulf Bernitz(Authors)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- Hart Publishing(Publisher)

4 The Scottish Parliament and the European Union: Analysing Regional Parliamentary Engagement CAITRÍONA CARTER AND AILEEN M C LEOD INTRODUCTION I N SCOTLAND, THE UK Labour Government’s devolution policy of the late 1990s was officially launched in July 1997 with the publication of the White Paper ‘Scotland’s Parliament’. 1 Subsequently, and following a successful referendum result, the Scotland Act was passed in Westminster in November 1998. Devolution took effect on 1 July 1999. Since then, the framework legislation has been further supplemented by an increasing body of ‘soft law’—notably, Concordats, Departmental Guidance Notes, Inter-parliamentary Agreements and Conventions. 2 Collectively, these instruments create the framework for the emergence of both the Scottish Executive and the Scottish Parliament as political institutions. That these new institutions would have a role to play in UK-European affairs was an integral part of the devolution settlement. Under the Scotland Act 1998, the Scottish Parliament was given the authority to issue both primary and sec-ondary legislation to develop a number of policies, including policies for which the EU also has a competence. Counted amongst these were policies of some economic and social significance for Scotland—for example, justice, fisheries, agriculture, environmental policy and economic development. And yet, this devolution of powers notwithstanding, the UK Government continued to reserve the right of negotiation in all matters at EU level, including those policies con-sidered devolved. Furthermore, the UK Government also retained its legal power 1 Cm 3658 (1997). Devolution was launched in Wales with the publication of a White Paper in July 1997. This chapter does not cover the process of devolution in Wales—see J Osmond and B Jones (eds), Birth of Welsh Democracy: The First Term of the National Assembly for Wales (Cardiff, Institute of Welsh Affairs and the Welsh Governance Centre, 2003).- eBook - ePub

- Alex Wright(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

It is also possible to view the current changes from a different theoretical perspective which seeks to ground federalism in society, and in social practices, rather than in institutions (Paterson 1994: 20). On this view federalism is created and sustained by the collaborative practices of economic, political, social and cultural life. The Parliament can then be seen as an institutional and democratic form, which is much more relevant to, and reflective of, modern Scotland.The actual mechanisms which evolve to secure the management of the new democracy are likely to do so under two sets of pressures: first, what is required to make the new system of government work; and, second what other devices are possible and politically acceptable in the new context of extended democracy. Perhaps we may expect the first category to be more consensual, and the second to be more characterised by discussion and disagreement.Mechanisms for Achieving Co-operation and Mutual Consideration

The Political Parties

The Labour Party, as the party of government in Westminster and the largest party in Scotland's coalition government, seems likely to seek policy consistency in England and Scotland, at least in the UK government's priority areas where there is devolved responsibility, education, for example. Clearly this would be more difficult to achieve in a situation where different parties controlled the parliaments.Perhaps the most important set of mechanisms is provided by the political parties and their modes of conduct, towards each other and internally. Following the clear outcome of the 1997 Referendum, and its acceptance by the Conservative Party, all of the significant political forces in Scotland supported the Parliament. All of the parties present in the Edinburgh Parliament, with the exception of the Greens, also have a presence elsewhere in the multi-layer system. The main parties also have MPs in the Westminster Parliament, although the Conservatives do not have any members elected from Scotland. - eBook - PDF

- Jean McFadden, Dale McFadzean(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- EUP(Publisher)

The first General Election to the Scottish Parliament was held in May 1999 and on 1 July the Parliament was formally opened by the Queen and assumed its full powers. THE POWERS OF THE Scottish Parliament The powers of the Scottish Parliament are not listed in the Scotland Act 1998. Instead, there are lists of the powers which the UK Parliament decided not to devolve to the Scottish Parliament. These are said to be reserved to the UK Parliament. Any power which is not listed is assumed to be devolved to the Scottish Parliament and within its legislative competence. This means that the Scottish Parliament has the power to make law in these areas. However, because the UK Parliament remains the supreme law-making body for the UK, that Parliament retains the power to make laws for Scotland in the devolved areas. Matters reserved to the UK Parliament The reserved matters are listed in Sch 5 to the Scotland Act 1998. There are general reservations and specific reservations. General reservations include: • the Crown; • the Union of Scotland and England; • the UK Parliament; • the continued existence of the Scottish High Courts; • most aspects of foreign affairs; • the defence of the realm; • the armed forces; • the registration and funding of political parties; • the Civil Service; • treason. Specific reservations are too detailed to list here in their entirety. They are grouped under 11 heads and include: - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Learning Press(Publisher)

Arguments that it will lead to Scottish independence Popular arguments against the Parliament before the UK general election of 1997, levelled by the Conservative Party, were that the Parliament would create a slippery slope to Scottish independence, and provide the pro-independence Scottish National Party with a route to power. John Major, the Conservative Prime Minister before May 1997, famously claimed the Parliament would end 1000 years of British history, although the Acts of Union uniting the two countries were still less than 300 years old at the time. The equally pro-Union Labour Party met these criticisms by claiming that devolution would fatally undermine the SNP, and remedy the long-felt desire of Scots for a measure of self-government. West Lothian Question A further procedural consequence created by the establishment of the Scottish Parliament is that Scottish MPs sitting in the British House of Commons are still able to vote on domestic legislation that applies only to England, Wales and Northern Ireland - whilst English, Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish Westminster MPs are unable to vote on the domestic legislation of the Scottish Parliament. This anomaly is known as the West Lothian Question and has led to criticism. Costs The escalating costs of the construction of the new Parliament building led to widespread criticism. Miralles' new Scottish Parliament building opened for business on the 7 September 2004, three years late. The estimated final cost was £431 million. The White Paper in 1997 estimated that a new building would have a net construction cost of £40 million, although this was based on the presumption that the old Royal High School building (since renamed 'New Parliament House') would be used, as had long been assumed. - eBook - PDF

The Scottish Electorate

The 1997 General Election and Beyond

- A. Brown, D. McCrone, L. Paterson, Paula Surridge(Authors)

- 1998(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

6 The Scottish Parliament INTRODUCTION In the run-up to the general election the Labour Party had promised Scotland a referendum on the establishment of a Parliament and, shortly after taking over government, passed legislation allowing the referendum to take place. Held on the 11 September 1997, the referendum asked people in Scotland to vote on two issues: whether or not a Parliament should be established and whether a Parliament should have tax varying powers. Scotland awoke on the 12 September to the news that the people had supported both propositions by impressive majorities. In this chapter we deal with two main aspects of the debate about a Scottish Parliament. The first is to examine three competing explanations of voting behaviour and assess how well they explain the result in the referendum of 11 September. One of these explanations is a model of voting based on rational choice theory, the second is a claim that social location (for example, social class) can explain voting patterns, and the third is a model based on vote as an expression of national identity. We argue that understanding the vote in the referendum requires a model based not on economic rationality or on national identity but rather on welfare rationality. That is, people in Scotland voted for a Parliament with tax varying powers because they believed it would bring benefits to Scotland in terms of social welfare. The second aspect of the debate is to consider the role which the issue of a Scottish Parliament played in the general election. In 1992, 114 The Scottish Electorate the Conservatives claimed that their defence of the constitutional status quo was a reason why their vote held up, and yet, in 1997 with the same policy, they lost all their seats in Scotland and a third of their remaining vote. Was the issue of a Scottish Parliament a factor in this collapse? We focus primarily here on the question of how people intended to vote in the referendum. - eBook - PDF

- Roger Mortimore, Andrew Blick, Roger Mortimore, Andrew Blick(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

The Queen opened the new Parliament on 1 Jul 1999. It moved into its new building in September 2004. In May 2007 the S.N.P. formed a (minority) government for the first time. This prompted the formation by the parties opposed to Scottish independence of the cross-party Commission on Scottish Devolution (‘the Calman Com- mission’), with Sir Kenneth Calman in the chair. The commission reported in June 2009, arguing for a considerable extension of Scottish revenue-raising powers and further specific devolution from Westminster. The Scotland Act, 2012, based on the Calman proposals, expanded the fiscal powers of the Scot- tish Parliament, and enhanced its legislative authority in certain areas. In May 2011 the S.N.P. retained power, winning a majority of seats in the Scottish Parliament. The UK government conceded that a referendum on Scottish independence could take place, the terms of which were established in the Edinburgh Agreement of October 2012. In a referendum on 18 Sep 2014 (see p. 449), Scotland voted against independence by 55.3% to 44.7% on an 18 DEVOLUTION 773 84.6% turnout. During the campaign, leaders of the three main Westminster parties—David Cameron (Conservative, Prime Minister), Nick Clegg (Lib- eral Democrats, Deputy Prime Minister) and Ed Miliband (Labour, Leader of the Opposition)—issued ‘The Vow’. This pledged further devolution of taxa- tion power, and included further commitments, such as the permanency of the Scottish Parliament and the Barnett Formula for the allocation of funds within the United Kingdom, should the Scottish electorate choose to remain within the Union. The details of how to implement ‘The Vow’ were agreed by the Smith Commission in November 2014, parts of which were implemented through the Scotland Act 2016. The Scottish Executive (1999–2007)/Scottish Government (2007–) First Minister Deputy First Minister 1 Jul 99 D. Dewar (Lab.) 1 Jul 99 J. Wallace (Lib Dem) 27 Oct 00 H. - eBook - PDF

Toward an Anthropology of Government

Democratic Transformations and Nation Building in Wales

- W. Schumann(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

Rather than to provide accountability or representation, the function of the Scottish Parliament elections may simply be to act as a ritual that provides that legitimacy [to the government]. But whether in the long run ritual alone will be sufficient to maintain the interest and participation of voters in Scottish Parliament elections is perhaps a more debatable question. I have argued that a significant conundrum democratic institutions face—and particularly those at the bottom rungs of Europe’s multisited, 172 TOWARD AN ANTHROPOLOGY OF GOVERNMENT asymmetrical universe of governance—is that legitimacy is not a singular , prefigured condition of democracy, but a pluralized set of practices that do not by necessity overlap and corroborate each other. Decentralized parliamentary power must be justified across a range of cultural, political party, legal/procedural, state/supranational, and economic lines that complicate the meaning(s) of empowerment that devolution is ultimately premised on. This book has arrived at the conclusion that the representation of public interests through parlia- mentary governance is secondary to the reproduction of political power through the institutional networks of devolved government, even if both are necessary components of democratic practice in Wales. Despite these complications—and because of them—I now turn to advocate for a more fully empowered Parliament of Wales even while admitting that such a change in the balance of UK power will not by necessity resolve the tensions between the institutional and representative legiti- mation of Welsh democracy . - eBook - PDF

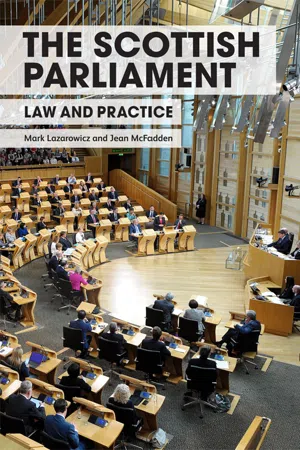

The Scottish Parliament

Law and Practice

- Mark Lazarowicz, Jean McFadden(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Edinburgh University Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER FOUR How the Parliament Works INTRODUCTION The supporters of the establishment of a Scottish Parliament frequently expressed the hope that such a body would be a new type of institution, with a new approach to the way in which the business of government is carried out. 1 This chapter looks at the way in which that hope has been reflected in the reality of the arrangements made for the way the Parliament works. It considers in some detail the role of the Parliament’s committees. It also looks at the opportunities that are available to MSPs to hold the Scottish Government to account, and the way in which exter-nal individuals and organisations can influence the Parliament’s work. THE LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK The Parliament is given a relatively free hand by the Scotland Act 1998 (SA 1998) in deciding how it should work. The Act does not set out detailed requirements for the Parliament’s method of operation. It states that the proceedings of the Parliament will be regulated by standing orders. 2 Beyond that general requirement, there is only a small number of areas where the SA 1998 specifies what should be in the standing orders. These statutory requirements contain important provisions about the passage of legislation, including procedures to ensure that the Parliament cannot make legislation on matters which are outside the powers given to it. These provisions are explained in Chapter 5 below. There is a number of other specific matters which the SA 1998 requires the Parliament to deal with in its standing orders, including rules to provide for the following: 3 • The preservation of order in the Parliament’s proceedings, includ-ing the prevention of criminal conduct or contempt of court during - eBook - PDF

- Tom M. Devine(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Edinburgh University Press(Publisher)

That high degree of policy-making autonomy is underlined by a system of territorial finance which awards an unconditional block grant to the devolved admin-istrations, again lacking any mechanisms for pursuing UK-wide objectives, and a system of intergovernmental relations which lacks structure and sanction (see further under point 4, below). That permissiveness is amplified by the different dynamics of gov-ernment formation produced by the distinctive party and electoral systems in operation outside England. In Scotland the classic left– right axis of party competition is supplemented by an additional axis of nationalism versus unionism. The presence of nationalist parties exerts a pull on the UK-wide parties (Labour, Conservative and Liberal Democrat), giving, say, Labour in the Scottish Parliament a different strategic landscape to negotiate than Labour in Westminster. 5 The broadly proportional electoral system in Scotland underlines the strategic pull away from UK-level party considerations by requiring greater degrees of cross-party cooperation in the coali-tion and minority government situations that Scotland has seen since 1999. The outcome of this permissive institutional and political context is a growing degree of territorial policy variation. This is, of course, to an extent what devolution was for, to open up the prospect of dis-tinctive policies better reflecting devolved preferences. Somewhere, however, there is a tipping point where the scope for autonomy begins to rub up against the content of common citizenship which member-ship of a union implies. There are, for example, periodic concerns in England about the different regimes for National Health Service 198 Charlie Jeffery

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.