History

Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale was a pioneering figure in the field of nursing during the 19th century. She gained prominence for her work in improving healthcare and hospital conditions, particularly during the Crimean War. Nightingale's emphasis on hygiene, sanitation, and patient care revolutionized nursing practices and laid the foundation for modern nursing education and standards.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Florence Nightingale"

- eBook - ePub

- Britannica Educational Publishing, Kara Rogers(Authors)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Britannica Educational Publishing(Publisher)

The nursing profession also has been strengthened by its increasing emphasis on national and international work in developing countries and by its advocacy of healthy and safe environments. The international scope of nursing is supported by the World Health Organization (WHO), which recognizes nursing as the backbone of most health care systems around the world.Florence Nightingale

(b. May 12, 1820, Florence [Italy]—d. Aug. 13, 1910, London, Eng.)Florence Nightingale was a statistician and social reformer and the foundational philosopher of modern nursing. Nightingale was put in charge of nursing British and allied soldiers in Turkey during the Crimean War. She spent many hours in the wards, and her night rounds giving personal care to the wounded established her image as the “Lady with the Lamp.” Her efforts to formalize nursing education led her to establish the first scientifically based nursing school—the Nightingale School of Nursing, at St. Thomas’ Hospital in London (opened 1860). She also was instrumental in setting up training for midwives and nurses in workhouse infirmaries. She was the first woman awarded the Order of Merit (1907).FAMILY TIES AND SPIRITUAL AWAKENINGFlorence Nightingale was the second of two daughters born, during an extended European honeymoon, to William Edward and Frances Nightingale. (William Edward’s original surname was Shore; he changed his name to Nightingale after inheriting his great-uncle’s estate in 1815.) Florence was named after the city of her birth. After returning to England in 1821, the Nightingales had a comfortable lifestyle, dividing their time between two homes, Lea Hurst in Derbyshire, located in central England, and Embley Park in warmer Hampshire, located in southcentral England. Embley Park, a large and comfortable estate, became the primary family residence, with the Nightingales taking trips to Lea Hurst in the summer and to London during the social season.Florence was a precocious child intellectually. Her father took particular interest in her education, guiding her through history, philosophy, and literature. She excelled in mathematics and languages and was able to read and write French, German, Italian, Greek, and Latin at an early age. Never satisfied with the traditional female skills of home management, she preferred to read the great philosophers and to engage in serious political and social discourse with her father. - eBook - ePub

- Robert Dingwall, Anne Marie Rafferty, Charles Webster(Authors)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Chapter three The New Model Nurse

One of the great problems for anybody studying the history of nursing in the nineteenth century is to find a way of coming to terms with the powerful and enigmatic figure of Florence Nightingale, a woman who became the stuff of which myths are made even in her own lifetime. In this chapter, however, we shall try to place her in a social context as a woman of her class and time. As we have seen, the care of the sick was already changing in many ways which were ultimately to produce the modern occupation of nursing. Florence Nightingale’s work was part of that process and undeniably made a major contribution to its outcome. But that result was a compromise between Miss Nightingale’s vision and the realities of mid-Victorian life, values and institutions; a compromise shaped by the hands of many other women and men. The ‘New Nurse’ turned out to retain a surprisingly large number of features of the old.Florence Nightingale: woman and myth

The difficulty of assessing the contribution of Florence Nightingale to nursing reform in the nineteenth century is that so much of the writing about her has been biographical rather than historical. This has, perhaps, been encouraged by the mass of her own papers which present vivid, if often selective, melodramatic and egotistic accounts and judgements of other people and events. Florence Nightingale’s life has taken on the function of a ‘heroine legend’ in nursing, a morality tale to inspire her successors (Whittaker and Oleson 1964). To see her, rather, as part of a social movement is not to detract from her contribution but is to acknowledge the complex relationship between individuals and their circumstances in the making of history.Thus, some of the more breathless accounts of her early life try to trace Florence Nightingale’s mission to nursing in events of her childhood and youth, an attempt in which they are encouraged by her own reconstructions in late middle age. Cook (1913:14), her first scholarly biographer, puts these in perspective: - eBook - PDF

- Syed Farid Alatas, Vineeta Sinha(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

Nightingale volunteered her services as a nurse during the Crimean War. In November 1854, with 38 nurses Nightingale reached the Selimiye Barracks at Scutari where she estab- lished an efficient nursing department. It is her work here that led to Nightingale being christened ‘the lady with the lamp’ given her habit of walking the wards at night with a lamp and attending to the wounded soldiers. Those who hail Nightingale as the heroine of the Crimean War highlight that through her concerted reforms in nursing practices she reduced the mortality efforts in Scutari considerably. 2 Nightingale, guided by miasma theory but rejecting the germ theory of disease, focused on sanitary reform by highlighting the lack of ventilation, defective sewerage system and overcrowding as causative factors. 3 Nightingale’s formal association with social science and academia were limited but significant: She regularly submitted papers to the British Association for the Promotion of Social Science and she was the first woman member of the London Statistical Society. 4 Her work was directed primarily at medical reform, intended to register improvements in hospitals, nursing and sanitary conditions. Nightingale successfully established modern nursing as a secular profession: through training and education of nurses and, opening it to women of working class and middle class backgrounds and rescuing it from the stigma of a demean- ing, discredited occupation and bestowed respectability. 2 Stephen Paget. ‘Nightingale, Florence’ In Sidney Lee (ed) Dictionary of National Biography, Supplement 3. London: Smith, Elder & Co, 1912. 3 Hugh Small, Times Literary Supplement (2000). 4 Other encounters include the following: Reading a paper ‘Life or death in India’ at the meeting of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science, in Norwich in 1873; Being appointed an honorary member of the Bengal Social Science Association (formed in 1867 and dissolved in 1878) in 1869, L. - eBook - ePub

- Monica F. Baly(Author)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Chapter 9 The influence of Florence NightingaleFlorence Nightingale was literally a legend in her own day. Neither the miasma of sentimentality, nor the exegesis of psychologists nor modern scholarship can destroy her achievements. For the best part of 50 years she laboured unremittingly for the ‘sake of the work’. She is rightly remembered for her work in the Crimean War, but work for nursing is but a small part of her reforming zeal. The Army Medical Service possibly owes more to her than does nursing. She probably made a greater impact on Poor Law nursing than on general nursing, and her designs for hospitals and barracks have stood the test of time for a longer period than probably her presentday successors can expect for theirs. It is not for nothing that Cecil Woodham-Smith, her biographer, described her as The Greatest Victorian of them all’.1EARLY LIFEFlorence Nightingale was born in Italy in 1820 while her family was on the ‘Grand Tour’. Her parents were wealthy, and her mother, Fanny, was a great beauty and a successful hostess, W.E.N., her father, was a cultivated man with liberal views. As his estate was entailed the fact that there was no son was a disaster, but he took great pains with the education of his two daughters, Parthe and Florence, which he largely supervised himself. Neither girl inherited Fanny’s striking beauty, but Florence was graceful, quick and an apt pupil. However, she was not a comfortable child and did not fit into the restless round of the Nightingale homes. This was partly because she resented the unhealthy life of idleness, which resulted in depressive brooding. She tried to fill the emptiness by excessive devotion to favourite members of the large Nightingale family, to good works in the neighbourhood, and at one time she felt that she had a vocation for mathematics. There is no doubt but that her brooding and imagination led her to over-dramatise the situation, a tendency that remained with her for life, but which sometimes produced that telling aphorism. Then at the age of 17 years she received a ‘call from God’. Unhappy and taut she was in fact living in a dream world, but she was always adamant that the voice was clear, and although she did not then know what the voice called her to do it affected her subsequent decisions. In spite of this she went to Italy where she was a social success and where she became imbued with the idea of Italian freedom and liberation, in the cause of which she declared herself prepared ‘to go to the barricades’.2 - eBook - PDF

All Heal

A Medical and Social Miscellany

- R M Shaw, R A Bowen, G E Paget(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Butterworth-Heinemann(Publisher)

Florence Nightingale's achievements in the provision of this skilled aid and also, very importantly, in a most unfashionable devotion to the human dignity of each individual soldier, gave her in England power on the scale of Queen Victoria's, and a popularity far beyond that of the Queen. For the rest of her life Miss Nightingale used this power to achieve reforms based not only on her searing experiences for twenty months in this crucible of war, but also on a huge correspondence with people in many parts of the world, which gave her an almost unrivalled collection of facts on nursing, hospitals and sanitation, which she studied profoundly, analysed statistically, and marshalled for their utmost eifect in government reports and other documents. Her last years were clouded with mental deterioration and blindness. It is doubtful whether she could appreciate the significance of the award of the Order of Merit. Death, which she had expected if not daily, certainly weekly for over fifty years, occurred on 13 August 1910, sixty years ago. If anyone had ever lived each day of her life as if it were the last, it was Florence Nightingale. From her sickroom, Florence Nightingale put out a tremendous volume of reports, pamphlets, letters; there are said to be some 150 large volumes of her notes and letters in the British Museum alone. Most of these were concerned with nursing, hospital construction, district nursing, rural hygiene and rural health visitors, the health of the British army and sanitation in India. The books about her include Sir Edward Cook's official biography, Mrs. Cecil Woodham-Smith's enthralling story of her life, Sir Zachary Cope's perceptive observa-tions on her relations with the medical profession, and the biobiblio-graphy compiled by the late Mr. W. J. Bishop and by Miss Sue Goldie. I should like now to give you a number of quotations from Florence Nightingale's own writings. - eBook - PDF

The Crimean War and its Afterlife

Making Modern Britain

- Lara Kriegel(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

They occurred on all scales and in many locations, through monu- mental events and in personal tributes, through metropolitan occasions and in far-flung actions. Taken together, these acts worked, again and again, to uphold Florence Nightingale as the foremost heroine of the Crimean War, and to solidify her role as a leading figure in Britain’s island story. The need for cohesion and consensus at the Crimean moment pro- pelled Nightingale to the forefront of national consciousness, where she remained from the nineteenth century into the twenty-first. Yet, Nightingale faced criticisms from the outset, with her work and her legend finding skeptics in early days. There were those who doubted Nightingale’s crusade at its inception, and there were critics in the Royal Army Medical Corps, not to mention among the rival nursing sisterhoods in the East. Army officers regarded her as domineering and The Heroine 197 supercilious – “an interfering pain in the neck,” to use the 1990s parlance of the Guardian. Even her nurses found her heavy handed. These senti- ments, cautiously voiced in the nineteenth century, found wider expres- sion in the twentieth century, with the discovery of documents and the sale of letters. 195 Broader cultural critiques of Nightingale took shape as well, as the work of Lytton Strachey and his popularizers demonstrated. Across these years, critics additionally unsettled orthodoxies about the very efficacy of Nightingale’s labors in the East. While she pioneered modern statistics and modern nursing, she did not, singlehandedly, defeat the cholera. Some of her remedies, such as the use of water from contaminated sources rather than alcohol that threatened insobriety, proved to do more harm than good. 196 It was in the end, however, the nursing profession itself, along with the National Health Service (NHS), that dealt Nightingale a decisive blow. - eBook - ePub

British Politics, Society and Empire, 1852-1945

Essays in Honour of Trevor O. Lloyd

- David W. Gutzke(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Florence Nightingale reconsidered as the founder of modern nursingCarol HelmstadterFlorence Nightingale returned from the Crimean War a national heroine and the possessor of the £44,039 Nightingale Fund, the gift of a grateful nation to recognize ‘the noble exertions of Miss Nightingale in the hospitals of the East.’ She had full control of the money which was to be used for training nurses.1 A generation later, the Nightingale Training School which she established at St. Thomas’s Hospital had become the model for nurse training throughout the English-speaking world, and Nightingale was then and later hailed as the founder of modern nursing. But was she really? The four most distinguished scholars to explore Nightingale’s contributions to the development of the new nursing, Sir Edward Cook, Brian Abel-Smith, Monica Baly and Mark Bostridge, all agreed that she was.Cook’s brilliant biography, commissioned by the Nightingale family and published in 1913 only three years after her death, remains the benchmark against which all subsequent scholarly efforts are measured. Cook was sympathetic with his heroine while at the same time critical and objective, but he made one major exception. Although he saw Nightingale’s innumerable despairing outcries over the grievous failings of the Nightingale Training School, he gave the impression it was an instant, enormous success.2 The received wisdom is that he repeated the very dishonest publicity which Nightingale and the Nightingale Fund Council put out so as not to hurt her family or the struggling new profession.Apart from recognizing Nightingale as the founder of modern nursing, Abel-Smith’s History of the Nursing Profession dealt only briefly with Nightingale personally. As an economist specializing in health services, however, Abel-Smith identified the central problem of the Nightingale system: its inability to recruit and retain adequate numbers of women. He attributed this ongoing problem to later nursing leaders.3 In fact, Nightingale’s policies were a major cause. Monica Baly, in her ground-breaking Florence Nightingale and the Nursing Legacy , was the first historian to demonstrate that the Nightingale Training School was not the success which Nightingale and her colleagues publicly claimed. She conclusively showed that what came to be called the Nightingale system was not what Nightingale wanted. Yet even the iconoclastic Baly thought her the founder of modern nursing, arguing that she created secular nursing.4 To the extent that the Nightingale School was not a sisterhood and accepted women of all religious denominations, it was secular, but this interpretation sits oddly with the fact that Nightingale desperately wanted her nurses to be deeply religious women, ‘hand-maidens of the Lord.’5 In his 2010 biography Florence Nightingale: The Making of an Icon , Mark Bostridge indicated that Nightingale has been heavily mythologized; much of what is believed to be the Nightingale tradition is legendary rather than historical. Nevertheless, Bostridge defended the Nightingale School as a ‘long-term success’ following major problems in the early years. This was in large part, he contended, due to John Croft, a senior surgeon at St. Thomas’s, whose annual series of 50 lectures helped lay the foundations of nursing knowledge.6 In fact, far fewer lectures were given, and the wards were often so busy that probationers were unable to attend them.7 - eBook - ePub

Myths That Shaped Our History

From Magna Carta to the Battle of Britain

- Simon Webb(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Pen & Sword History(Publisher)

Chapter 6

Florence Nightingale in Scutari 1854–1855: ‘A Lady with a Lamp shall stand, In the great history of the Land’

F lorence Nightingale is the very epitome of one of the British mythic archetypes at which we have been looking. She is the personification of the little person who takes on authority, standing up to the leadership of the British Army at the height of the Empire and bending them to her will. At a time when a woman’s place was most definitely in the home, here was one woman who not only refused to stay at home, but actually went to war in order to protect the welfare of wounded and ill men. The ‘Lady of the Lamp’ is the closest thing which the British have to a national heroine. She has even been awarded the accolade of appearing on the currency; from 1975 to 1994, Florence Nightingale was to be found on £10 notes, leading to that denomination becoming colloquially known as a ‘Nightingale’.There can surely be very little to say on the subject of Florence Nightingale’s work; this, after all, is the woman responsible for the establishment of nursing in its modern form. She raised nursing from being the occupation of drunken slatterns such as Sarah Gamp, in Dickens’ Martin Chuzzlewit, to the honourable profession which it is today.The difficulty with criticizing and deconstructing the myth of Florence Nightingale and her activities in Turkey is that it makes many people feel uncomfortable. It seems almost churlish and small-minded, a century and a half after her work, to pick apart and quibble over the details of what she actually achieved. After all, it must surely be indisputable that she at least did more good than bad and that the lot of those casualties of the Crimean War would have been far less pleasant and considerably more hazardous, had Florence Nightingale not taken charge of the hospital at Scutari? This is certainly the view of most people today. Here is what a popular children’s history book, published by the Oxford University Press, has to say on the matter: - eBook - ePub

The Times Great Women's Lives

A Celebration in Obituaries

- Sue Corbett(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- The History Press(Publisher)

Before returning to England Florence Nightingale had received from Queen Victoria an autograph letter with a beautiful jewel, designed by Prince Albert; the Sultan had sent her a diamond bracelet; and a fund for a national commemoration of her services had been started, the income from the proceeds, £45,400, being eventually devoted partly to the setting up at St Thomas’s Hospital of a training school for hospital and infirmary nurses and partly to the maintenance and instruction at King’s College Hospital of midwifery nurses. For herself she would have neither public testimonial nor public welcome. She was honoured by an invitation to visit the Queen and Prince Consort at Balmoral in September, and addresses and gifts from working men and others were sent or presented privately to her. But though her fame was on every one’s lips, and her name has ever since been a household word among the peoples of the world, her life from the time of her return home was little better than that of a recluse and confirmed invalid. Her health, never robust, broke down under the strain of her arduous labours, and she spent most of her time on a couch, while in the closing years of her life she was entirely confined to bed.But, though her physical powers failed her, there was no falling off either in her mental strength or in her intense devotion to the cause of humanity. She was still the “Lady-in-Chief” in the organization of the various phases of nursing which, thanks to the example she had set and the new spirit with which she had imbued the civilized world, now began to establish themselves; she was the general adviser on nursing organization not only of our own but of foreign Governments, and was consulted by British Ministers and generals at the outbreak of each one of our wars, great or small; she expanded important schemes of sanitary and other reforms, though compelled to leave others to carry them out, while at all times her experience and practical advice were at the command of those who needed them.Almost the entire range of nursing seems to have been embraced by that revolution therein which Florence Nightingale was the chief means of bringing about. Following up the personal services she had already rendered in the East in regard to Army nursing, she prepared, at the request of the War Office, an exhaustive and confidential report on the working of the Army Medical Department in the Crimea as the precursor to complete reorganization at home; she was the means of inspiring more humane and more efficient treatment of the wounded both in the American Civil War and the Franco-German War; and it was the stirring record of her deeds that led to the founding of the Red Cross Society, now established in every civilized land. By the Indian Government also she was almost ceaselessly consulted on questions affecting the health of the Indian Army. On the outbreak of the Indian Mutiny she even offered to go out and organize a nursing staff for the troops in India. The state of her health did not warrant the acceptance of this offer; but no one can doubt that, if campaigns are fought under more humane conditions today as regards the care of wounded soldiers, the result is very largely due to the example and also to the counsels of Florence Nightingale. - eBook - PDF

- Michael Schwartz, Howard Harris, Michael Schwartz, Howard Harris(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Emerald Group Publishing Limited(Publisher)

While writing this paper I have ended my nursing career of 40 years through sheer frustration because I feel that I cannot provide care that would do Nightingale proud, even less being able to practice the art that is the hallmark of a real professional nurse. I personally lack the kind of moral courage and persistence that I have praised Nightingale for throughout this article. On the 100th anniversary of Nightingale’s death Bostridge wrote an article for The Guardian titled ‘Could Florence Nightingale nurse us back to A Book Review of Mark Bostridge’s Florence Nightingale 191 health?’ In his introduction he lists her achievements; I quote it as a summary of the key aspects of his biography of her: Nightingale was one of the 19th century’s great polymaths. She was the emergent nursing profession’s most significant theorist, an expert in hospital design, a pioneer in evidence-based medical care and statistical analysis, a radical theological, a feminist who believed that woman should be permitted to lead independent lives (even while she remained ambivalent about the notion of women’s ‘rights’) – and much else besides. Bostridge points out both in his book and in the anniversary article that Florence Nightingale looked forward to a time when we, equipped with better skills and knowledge, would eradicate diseases and make the need for hospitals obsolete. She was committed to the prevention of disease through appropriate public health measures and to improve the general health of the members of the community. The readers of Bostridge’s wonderful book should appreciate it as a unique document on what health should be about. The true legacy of Nightingale is that we should be responsible for our own health and provide good primary health care in order to prevent the illnesses that cause people to overpopulate our hospitals in a way that would have horrified her more than a hundred years after her death. REFERENCES Bostridge, M. (2008). Florence Nightingale . - eBook - PDF

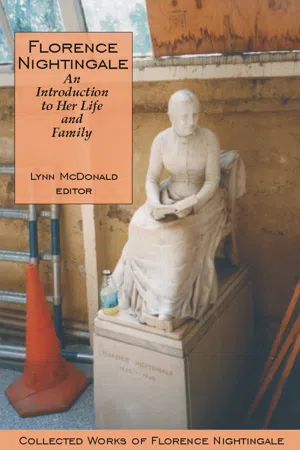

Florence Nightingale: An Introduction to Her Life and Family

Collected Works of Florence Nightingale, Volume 1

- Lynn McDonald(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Wilfrid Laurier University Press(Publisher)

Nightingale’s nursing establishment began with the thirty-eight nurses who travelled together to Scutari. A further contingent of forty-seven arrived in December, sent without Nightingale’s knowledge, which caused a row over her authority. Nightingale won and her authority was extended to nursing in the Crimea proper. Some of the doctors never accepted the presence of Nightingale and her nurses; others soon learned that going to ‘‘the bird,’’ as she was jokingly called, was the way to get things done. She had supplies that the Army either did not have, or did not know that it had because its record keeping was so bad. This would be the pattern throughout her long career of reorganizing society: there were supporters and 32 Letter to Parthenope Nightingale 2 June 1856, Wellcome (Claydon copy) Ms 8996/63. 28 / Florence Nightingale: Her Life and Family collaborators, enemies and upholders of the status quo. The nurses themselves, at Nightingale’s insistence, worked solely under the direc-tion of the doctors, the only way to get the doctors’ co-operation. The Nightingale method eventually worked in that the sanitary reforms she instituted helped to lower the high mortality rate. Most men died from disease, not bullets, a point she and her team would stress in all their reform work after the war: 19,000 from illness (mainly infectious diseases), 4000 from wounds. Nightingale regarded the deaths from ill-ness as unnecessary—anything above the ‘‘normal death rate’’ was. In the first months of the war Army losses were 60 percent. By the end, the mortality rate from illness was no greater than that of a comparable population in England, men in the industrial city of Manchester. In his Florence Nightingale: Avenging Angel , Hugh Small argues that Nightingale was initially mistaken about the causes of the high mortal-ity rate and that her superficial reforms (better diet, clean laundry, washing patients, etc.) were ineffective.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.