History

John Brown's Raid

John Brown's Raid was a failed attempt by abolitionist John Brown to initiate a slave rebellion by seizing the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859. Brown and his followers were quickly captured by U.S. Marines, and Brown was subsequently tried and executed for treason. The raid heightened tensions between the North and South and is considered a precursor to the American Civil War.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "John Brown's Raid"

- eBook - ePub

Lyrical Liberators

The American Antislavery Movement in Verse, 1831–1865

- Monica Pelaez(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Ohio University Press(Publisher)

5 JOHN BROWN AND THE RAID ON HARPERS FERRYJOHN BROWN EARNED a name for himself as an abolitionist crusader as early as 1855, when he proved his zealous commitment to the cause by going so far as to kill proslavery agitators during the border conflicts in the Kansas territory where he had settled with his sons (see chapter 4 ). Although he crossed paths with William Lloyd Garrison and his supporters on several occasions, he was notably overheard to complain at the New England Anti-Slavery Convention in 1859 that “these men are all talk; what is needed is action—action!”1 Matching his deeds to his words, on October 16, 1859, he led a raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in the hopes of inciting a slave uprising that would be armed with weapons seized from the town’s arsenal.2 Although his group succeeded in seizing several buildings and hostages, no slaves ultimately rallied to their cause, and the raiders were captured the following day by federal troops under the command of Colonel Robert E. Lee. Brown was subsequently tried for treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia, convicted, and hung. In the final speech he delivered during his trial he exonerated himself by arguing that his intention to free the slaves was in accordance with the New Testament, “that teaches me that all things whatsoever I would that men should do to me, I should do even so to them. It teaches me, further, to remember them that are in bonds, as bound with them.”3Although public opinion initially judged Brown’s actions as misguided, views shifted during the course of his trial and he increasingly came to be depicted as a martyr for the cause. Paul Finkelman has shown that Brown’s martyrdom “was shaped by the apparent unfairness of his trial, his letters from jail, his stoic behavior at the gallows, and the efforts of antislavery activists to exploit his execution for the greater cause.”4 Brown himself recognized how valuable his death would be to the movement in a letter confessing to his brother, “I am worth inconceivably more to hang than for any other purpose,” while Garrison also acknowledged that “John Brown executed will do more for our good cause, incomparably, than John Brown pardoned.”5 Indeed, on the day of his execution numerous meetings were held across the North to proclaim his martyrdom and condemn slavery through speeches and resolutions. The American Anti-Slavery Society notably dedicated its annual report of 1859 to “the memory of the noble hero-martyr.”6 He was cast in this role as well by leading authors of the time like Ralph Waldo Emerson, who referred to Brown as a “new saint” who “will make the gallows glorious like the Cross,” a sentiment that was echoed by others ranging from Herman Melville to Henry David Thoreau.7 The black activist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper had already anticipated the significance of his sacrifice when she wrote to Brown in prison, “if Universal Freedom is ever to be the dominant power of the land, your bodies may be only her first stepping stones to dominion.”8 - eBook - ePub

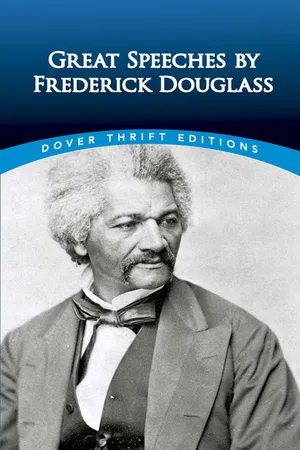

- Frederick Douglass, James Daley(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Dover Publications(Publisher)

John Brown (1881)John Brown gained notoriety throughout the 1850s as a revolutionary abolitionist who advocated armed rebellion as a means for ending the practice of slavery in the United States. He was executed shortly after leading 18 men on a raid of the Harpers Ferry Armory in 1859. In the following speech, delivered on May 30, 1881 at the Fourteenth Anniversary of Storer College, Douglass discusses the lasting impact of John Brown’s life on the history of Slavery in America.Not to fan the flame of sectional animosity now happily in the process of rapid and I hope permanent extinction, not to revive and keep alive a sense of shame and remorse for a great national crime, which has brought its own punishment, in loss of treasure, tears and blood, not to recount the long list of wrongs, inflicted on my race during more than two hundred years of merciless bondage; nor yet to draw, from the labyrinths of far-off centuries, incidents and achievements wherewith to rouse your passions, and enkindle your enthusiasm, but to pay a just debt long due, to vindicate in some degree a great historical character, of our own time and country, one with whom I was myself well acquainted, and whose friendship and confidence it was my good fortune to share, and to give you such recollections, impressions and facts, as I can, of a grand, brave and good old man, and especially to promote a better understanding of the raid upon Harper’s Ferry of which he was the chief, is the object of this address.In all the thirty years’ conflict with slavery, if we except the late tremendous war, there is no subject which in its interest and importance will be remembered longer, or will form a more thrilling chapter in American history than this strange, wild, bloody and mournful drama. The story of it is still fresh in the minds of many who now hear me, but for the sake of those who may have forgotten its details, and in order to have our subject in its entire range more fully and clearly before us at the outset, I will briefly state the facts in that extraordinary transaction. - eBook - PDF

Voices of the American Civil War

Stories of Men, Women, and Children Who Lived Through the War Between the States

- Kendall Haven(Author)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Libraries Unlimited(Publisher)

Not one mulatto, free black, or white abolitionist rallied to Brown's cause. John Brown was hanged by the Virginia authorities. His last words were, "I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of these guilty lands will never be purged away but with blood." 1 The raid was a total flop, and a costly one. Two slaves, one free black (Hayward Sheppard, the baggage handler), one marine, three townsmen, and 10 raiders (includ- ing two of Brown's sons) died. Six raiders were captured (including three who were caught in the Maryland schoolhouse) and later hanged. Two of the escaped raiders were later hunted down and shot. Three escaped and were never apprehended. Yet the raid had monumental effects. Fearing that another abolitionist would try to raise a slave army in other locations, militia units were formed and drilled in virtually every Southern community. These units began intense training. Eighteen months after the raid these same militia units would become the backbone of the Southern armies. At the same time, Northern abolitionists were strengthened and emboldened in their political positions by Brown's "noble" attempt to free the slaves. Congress was further polarized, both sides becoming less willing to compromise and less interested in searching for common ground. At a time when steps toward peace were essential, Brown's raid forced both sides to entrench themselves in their strongest, most uncom- promising positions and sent the nation hurtling toward preparations for war. Notes 1. Joseph Barry, The Strange Story of Harpers Ferry, p. 137. Follow-up Questions and Activities 1. What Do You Know? • Why did John Brown attack Harpers Ferry? What did he hope to accomplish there? • Why didn't he grab the arsenal's guns and leave? Why did Brown feel he had to stay and wait at Harpers Ferry? - eBook - PDF

Ambivalent Conspirators

John Brown, the Secret Six, and a Theory of Slave Violence

- Jeffrey Rossbach(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

Brown chose to launch his raid at Harpers Ferry because it housed a federal armory where firearms and munitions were manufactured for the army. He knew it would take more than Stearns's 200 revolvers, Massachusetts Kansas's 198 Sharpe's rifles, and the 1,000 pikes now being shipped to his backup base in Chambersburg, a few miles north, to properly supply the slaves who rallied to his banner. Brown rented a small farmhouse north of town to serve as his headquarters and immediately began poring over maps and making final preparations. Brown consulted with John E. Cook, a recruit who had been living in the area for almost a year doing reconnaissance work at his request. In late July, Brown settled on his final plan of attack. He decided to storm the federal armory (a large multipurpose structure containing a fire engine house, forge, machine, and stocking shops, and an arsenal, or storehouse), then take over and loot the arsenal. The raiders would hold the entire complex briefly, while word went out to slaves in the surrounding area. When enough slaves had joined him, he would lead the entire group south, inciting further insurrection as he went. He would not, as he had often suggested, retreat to a moun-tain fortress. Brown was surprised by the angry reaction which greeted his revela-tion of the plan's last feature. Threats of mutiny arose among his small cadre; tension mounted in the heat and confinement of his base. As he struggled to hold his tiny band together and prepare the assault, Brown faced other difficulties as great as his men's discontent. He was disap-pointed that so few men had joined him from the North. For over a year and a half he had partially revealed or, at least, vaguely alluded to his scheme among approximately eighty abolitionists, black and white. Few (except the Six) had done anything to finance the venture, but a number had promised to recruit raiders for the attack. - eBook - ePub

The United States Marines in the Civil War

Harpers Ferry and The Battle of First Manassas

- Major Bruce H. Norton(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Academica Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER 1The United States Marines and John Brown’s Raid

On July 3, 1859, John Brown arrived in Harpers Ferry, 61 miles northwest of Washington, DC, in what was then the Commonwealth of Virginia (now, West Virginia), accompanied by his two sons, Oliver and Owen, and Jeremiah Anderson. In the preceding months, he had raised money from other abolitionists and ordered pikes, guns, and other weapons to be used in his war against slavery. Using the alias Isaac Smith, Brown rented the Kennedy Farm, located about five miles from the Federal Armory, on the Maryland side of the Potomac River.Throughout the summer Brown’s Army gathered at the farmhouse. Numbering 21 at the time of the raid, these men stayed hidden in the attic by day, reading, writing letters, polishing their rifles, and playing checkers. To avoid being seen by curious neighbors, they would only come out at night.(John Brown – 1859)To keep up the appearance of a normal household, Brown sent for his daughter, 15-year-old Annie, and Oliver’s wife, 17-year-old Martha. The girls prepared meals, washed clothes, and kept nosy neighbors at a distance. Brown studied maps and conferred with John Cook, his advance man in the Ferry, about the town, armory operations, train schedules, and other information deemed valuable to his plan. On September 30, Brown sent Martha and Annie home to New York. The time was near.(Annie Brown - John Brown’s Daughter)On Sunday, October 16, Brown called his men together. Following a prayer, he outlined his battle plans and instructed them, “Men, get your arms; we will proceed to the Ferry.”(Martha Brown, John Brown’s Daughter-in-Law)“Harpers Ferry was the site of a major federal armory, including a musket factory and rifle works, an arsenal, several large mills and an important railroad junction and was one of the most heavily industrialized towns south of the Mason-Dixon line,” said Dennis Frye, the National Park Service’s Chief Historian at Harpers Ferry. “It was also a cosmopolitan town, with a lot of Irish and German immigrants, and even Yankees who worked in the industrial facilities.” The town and its environs’ population of 3,000 included about 300 African Americans evenly divided between slave and free. But more than 18,000 slaves – the “bees” Brown expected to swarm – lived in the surrounding counties. - eBook - ePub

Fanatics and Fire-eaters

Newspapers and the Coming of the Civil War

- Lorman A. Ratner, Dwight L. Teeter Jr.(Authors)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- University of Illinois Press(Publisher)

During 1858 and well into 1859, taking advantage of his friendship with the wealthy New York philanthropist and abolitionist Gerrit Smith, Brown made several train trips east to meet with abolitionists who might assist him in his cause. Just how much of his plan Brown revealed to those abolitionists has remained a mystery, but we do know that he sought and received money from several of them, including Smith. With those funds he rented a farmhouse near Harpers Ferry, Virginia, a town on the Potomac River in northwestern Virginia, some ninety miles from Richmond and Washington and connected by rail to both cities. He also ordered a large number of spikes from a manufacturer in Connecticut, to be used by slaves as weapons, and in time brought several men from Kansas and elsewhere, including one of his sons, to Virginia. His plan was to seize a federal arsenal located in that village, take the arms stored there, and distribute them to slaves. Once armed, he would lead those slaves in an uprising against their masters. Brown believed that as word of the rebellion spread a slave insurrection would engulf the South.On the morning of October 17, 1859, the telegraph wire services began to receive reports that they passed on to their newspaper clients. A violent conflict had occurred the day before in the town of Harpers Ferry. Details were sketchy. Newspapers were uncertain about who had initiated the violence and why. Some accounts reported that as many as seven to eight hundred workers, angry over pay and working conditions at a local construction site, had attacked the town’s citizenry. Others declared the event to be a massive uprising of slaves, a servile insurrection. Men had been shot and killed, but how many was also unclear.By October 18 the details about what had happened became known and were communicated over the telegraph. In another day or two newspapers in all parts of the country were telling readers about John Brown, late of Kansas, who with a small band of white men and a few free blacks had assaulted the federal arsenal located in Harpers Ferry. Having neglected to cut the telegraph line out of Harpers Ferry, the attackers soon had to face a company of federal troops commanded by Col. Robert E. Lee. Brown and his men barricaded themselves inside the arsenal. Lee’s men stormed it, killing several of the small band and wounding and capturing Brown and the others.2Newspapers everywhere soon carried story after story about the raid and the discovery of what to some appeared to be evidence that Brown and his men were part of a wider conspiracy. When Virginia authorities searched the rented farmhouse that Brown used as a staging area, they found letters from a number of well-known northerners. There was proof that Brown had been in touch with the fugitive slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Also among his correspondents was the noted Boston Unitarian minister Theodore Parker, who had been involved some years before in the attempt to free Anthony Burns, an accused runaway slave. Parker and others had used force to keep Burns out of the hands of slave-catchers, thus defying the Fugitive Slave Act. There were also letters from others sympathetic to abolitionists, including some members of Congress. - Ethan J. Kytle(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Brown intended “to light up the fires of a ser- vile insurrection, and to give your dwellings to the torch of the incendi- ary, and your wives and children to the knives of assassins,” Mississippian Fulton Anderson told the Virginia Secession Convention in early 1861. His “daring outrage on your soil” was “the necessary and logical result of the principles, boldly and recklessly advanced by the sectional party . . . which is now about to be inaugurated into power.” Despite Lincoln’s dis- avowal of Brown’s methods, suggested Anderson, the president had been elected by a northern public seemingly sympathetic to the violent destruc- tion of the southern way of life. A Lincoln administration, in sum, spelled more Harpers Ferry raids to come. 85 In a strange twist of fate, then, Brown’s botched attack – at least as recast by Higginson and fellow romantic reformers – had helped deliver the very homeopathic dose to the American body politic Higginson had long desired. As the New Romantic wrote to Brown’s family in early November, “He has failed in his original effort only to succeed in greater result. The utmost good he could have done by success does not equal the good destined to follow this failure.” 86 In search of something to speed the United States toward disunion and civil war, Higginson realized, he could not have asked for a better remedy than John Brown’s raid. The Culmination of the Training of a Life In late December 1860, just days after South Carolina voted unanimously to leave the Union, Higginson wrote his mother that he was finally approaching “the mode of life” that he desired. 87 Having given up his Free Church pulpit in early 1858, he had, over the last few years, become a regular contributor to the Atlantic Monthly. After nearly a decade of militant antislavery activity, punctuated by moments of physical confron- tation with proslavery forces, Higginson spent most of 1859, 1860, and 1861 acting the intellectual rather than the revolutionary.- eBook - PDF

The Press on Trial

Crimes and Trials as Media Events

- Lloyd E. Chiasson(Author)

- 1997(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

To free blacks and slaves, the leader at Harpers Ferry was more than a man—he was a symbol who conferred dignity and worth upon his black followers. This devotion to Brown, with his condemnation of slavery as the sin of all sins, motivated many blacks to follow him without question. 3 Fear that Brown's failed raid at Harpers Ferry might ignite a great slave uprising was real. Andrew Hunter, appointed as special prosecutor by the governor, seemed to agree that the "raid was not the insignificant thing which it appeared to be before the public, but that it. . . was the incipient movement of the great conflict between North and South." 4 This was perhaps the greatest fear of Southerners: not the threat of war so much as the potential for slave insurrections and the crumbling of a way of life. Activities of all blacks in the South, even seemingly innocent actions, were viewed with suspicion. Initial reports of the raid stated that as many as 600 to 900 Negroes were expected to revolt. 5 Even during Brown's incarceration, rumors circulated that an army of slaves and abolitionists were plotting to march across Virginia's borders and free Brown. This scenario had the antislavery army massacring all white men, women, and children, while burning everything in their path. 6 Newspapers capitalized on this hypothetical, citing numerous incidents of Southern paranoia. According to a Richmond Enquirer article, reprinted in the New York Times, the raid was proof that abolitionists were madmen determined to undermine the rights of slaveholders in the South. 7 During the siege at Harpers Ferry, Baltimore newspapers printed detailed stories of a dangerous ringleader who commanded 300 "strapping negroes" (later 500 to 700) who were slaughtering whites and causing a great deal of trouble. 8 And on October 27 the New Orleans Daily Picayune asked the question no one in either region wanted answered: "Are the thinking men of the North ready for - eBook - PDF

Harriet Tubman

The Life and the Life Stories

- Jean M. Humez(Author)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- University of Wisconsin Press(Publisher)

Moreover, Sanborn later said that on the day of the Harpers Ferry Raid (October 16) she was in New York and was able to predict to her “hostess” that something had happened to John Brown (Sanborn, 1863). For better or for worse, Tubman did not play a significant role personally or even through gathering recruits for John Brown’s paramilitary action at Harpers Ferry. The story of the raid itself is quickly told. Eighteen of John Brown’s band of twenty-one followers, five of them black, temporarily took posses- sion of the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in a surprise attack on October 16. The three others waited at the base camp, called the Kennedy Farm, while the raid took place. The invaders were defeated just over twenty-four hours later when federal troops under Robert E. Lee arrived, and no slave uprising occurred. Ten of the party were killed, including two of John Brown’s sons, Oliver and Watson, in the retaking of the arsenal by the troops. Seven were captured, including John Brown. Five escaped, in- cluding Owen Brown, one of John Brown’s sons, and Osborne Anderson, the one black Canadian recruit. John Brown and four surviving captured associates, two of them black, were quickly tried, condemned, and exe- cuted—amid a vast outpouring of publicity, north and south. Several of the Secret Six co-conspirators and other associates of Brown fled to Canada to avoid possible arrest and treason trials in Virginia. 59 A Senate committee led by James Mason of Virginia investigated Brown’s activities by interviewing white witnesses and combing through captured documents. The committee expected to find evidence of wide- spread complicity in a plot to foment slave insurrection, but failed to do so. 60 Martyr Day ceremonies were held across the North and in Canada on December 2, the day John Brown was executed. - eBook - PDF

In the Name of God and Country

Reconsidering Terrorism in American History

- Michael Fellman(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Yale University Press(Publisher)

To your tents! Organize and Arm!’’ ∑∂ Wise expressed the near-unanimous views of southern white leaders. All over the South, amid rumors of insurrection and arson, legislatures com-mitted considerable sums of money to rearm state militias, and they hounded suspected northern spies, as well as people who expressed doubt about south-ern righteousness, into silence or flight. ∑∑ John Brown had lit the fuse of secessionism. The Mobile Daily Register editorialized, ‘‘The Harpers Ferry Tragedy is like a meteor disclosing in its lurid flash the width and depth of that abyss which rends asunder two nations, apparently one.’’ Believing that all northerners supported Brown in their hearts, the editors of the Richmond Enquirer declared that ‘‘the Harpers Ferry invasion has advanced the cause of disunion more than any other event [and] the people of the North sustain the outrage.’’ There could be only one response, the Savannah Republican agreed: ‘‘Like the neighboring population we go in for summary vengeance. A terri-ble example should be made.’’ ∑∏ Hunger for retaliation lay at the core of the reactionary impulse in the South. This wave of hysteria spread among the white community. Women as well as men expressed their fury with Brown and their visceral fear of what was to come, demonstrating that Brown’s revolutionary terrorist mission had been accomplished. Amanda Virginia Edmonds, the twenty-year-old daugh-ter of the owner of a large plantation in Fauquier County, Virginia, for example, wrote in her diary after reading of Brown’s execution, ‘‘I would see the fire kindled and those who did it singed and burned until the last drop of blood was dried within them and every bone smouldered to ashes. - eBook - ePub

Nothing but the Truth

Why Trial Lawyers Don't, Can't, and Shouldn't Have to Tell the Whole Truth

- Steven Lubet(Author)

- 2001(Publication Date)

- NYU Press(Publisher)

Brown’s aim was not only to defeat the charge of murder, which he hoped to do by demonstrating that he had shown compassion rather than malice toward his captives, and by extension that he had no intention to murder anyone. But that goal was subordinate to his larger purpose, which was to enhance the image of his entire endeavor by emphasizing its humanitarian, rather than military, objectives. It would have been nearly impossible to engender sympathy in the North for a bloody invasion of peaceful Harpers Ferry (hence the need for a lawyer who was not an ultra-abolitionist). A much stronger case, however, could be made for a tempered mission to rescue slaves in which no property was to be damaged and “no unarmed person should be injured under any circumstances whatsoever.” And there began the reinvention of John Brown.Of course, the claim was false. Brown had no particular respect for southern property or for the lives of slave owners. He had proven as much by the killings in Kansas and Missouri. In fact, he believed that he was completely justified in taking lives, as he had explained early in the raid to his second hostage, the watchman Daniel Whelan: “I came here from Kansas, and this is a slave state; I want to free all the negroes in this State; I have possession now of the United States armory, and if the citizens interfere with me I must only burn the town and have blood.”Truthfully or otherwise, Brown’s case could best be presented to the world with the assistance of cooperative counsel. While the trial began with Botts and Green at the defense table, they were eventually dismissed.One northern lawyer did arrive near the beginning of Brown’s trial. In strictly professional terms, his conduct was far more questionable than anything done by Botts and Green.George H. Hoyt was a neophyte lawyer from Athol, Massachusetts. Only twenty-one years old, he appeared even younger. Within days of the Harpers Ferry raid, Hoyt was retained by John Le Barnes, a Boston abolitionist, and sent directly to Charlestown, ostensibly to assist in Brown’s defense.In reality, however, Hoyt was sent not as a lawyer but as an advance scout with directions to begin planning an escape attempt. Hoyt was instructed to send Le Barnes - eBook - PDF

Harriet Tubman

A Biography

- James A. McGowan, William C. Kashatus(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

But he was also too cautious to be more than an admirer and financier of their causes, lest he, too, “be caught” and “burned alive” like Tubman. Repeated postponements and poor communication prevented Brown from launching his assault for another year. It also prevented him from locating Harriet, who was busy giving talks to abolitionist audiences and tending to her parents and other relatives. 19 As a result, Tubman did not play any significant role on the day of the invasion, but she did have a premonition that he was in trouble. On October 16, 1859—the day of Brown’s raid at Harpers Ferry—Harriet was visiting friends in New York and told her hostess that “something was wrong, but she could not tell what.” Later that evening she came to the conclusion that “it must be Captain Brown” and told her friend that they would “soon hear bad news from him.” 20 The next day’s newspapers confirmed her worst fears. During the previous night, Brown set out for Harpers Ferry with 21 followers and a wagon full of supplies. Leaving three men behind to guard their base camp—a nearby farm—Brown’s guerillas slipped into town and easily seized control of the arsenal. To his surprise, however, none of the local slaves would join his revolt. Most were afraid that Brown would be unsuccessful and did not want to risk their lives for a fanatic. Even more incredible, Brown had made no provision for es- cape. Within three days, federal troops under the command of Colonel Robert E. Lee captured Brown and 6 of his men. Another 10 of his fol- lowers were killed in the ambush. Brown and his surviving men were convicted of treason, conspiracy, and first-degree murder. All the charges carried the death penalty. Throughout his trial, the radical abolitionist 86 HARRIET TUBMAN spoke passionately against slavery and accepted his death sentence with the calm resignation of a martyr.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.