History

Motion Picture Production Code

The Motion Picture Production Code, also known as the Hays Code, was a set of industry guidelines for the self-censorship of content in American films. It was implemented in 1930 and enforced until the late 1960s, aiming to maintain moral standards in cinema. The code regulated various aspects of filmmaking, including themes, language, and depictions of violence and sexuality.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Motion Picture Production Code"

- eBook - ePub

Sex and Violence

The Hollywood Censorship Wars

- Tom Pollard(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Chapter Three The Hays CodeHistorians usually employ the term Production Code to signify the period between 1934 and 1968 in which the Production Code Administration (PCA) held sway over film content and advertising. Will H. Hays, the first president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA), initiated and administered that code. Under Hays’s leadership the older production codes discussed in the previous chapter underwent refinement and codification, with some new elements interjected in 1930 by Father Daniel Lord, a Catholic professor of religious studies. Finally, the Hays Code began functioning in July 1934.From the beginning, the Hays Code imposed powerful rules and regulations governing motion picture content that constituted real censorship for the first time. For many, the rapidly evolving code became synonymous with Hays himself and eventually came to be referred to as the Hays Code, while Hays became known as “Mr. Hollywood.” The Production Code Administration, which oversaw the day-to-day applications, soon came to be called the Hays Office. During no other period of film history has one man dominated the Production Codes like Hays did. To fully appreciate the ramifications and nuances of the 1934 Hays Code, we need to turn to Hays’s earlier film regulator roles.In 1922 he became the first president of MPPDA, an organization ostensibly formed by the major studios to regulate filmmaking policies and to represent the producers in their interactions with the public. In fact, the organization served to blunt criticism of Hollywood, allowing filmmakers freedom to use any means to entice audiences. Hays proved adept at assuaging public displeasure over Hollywood’s scandals and permissiveness, negotiating with state and local censorship boards on behalf of producers and touting the agency’s largely nonexistent power to force changes in films. However, under the threat of a Catholic and allied faiths’ audience boycott and the behind-the-scenes machinations of powerful Catholic businessmen, studio executives reluctantly agreed to abide by a code that included serious provisions for enforcement. Hays then refined and adapted the latest iteration of previous codes that placed strict limitations on movie subject matter and advertising. The Hays Code eventually became the most long-lived set of filmmaking rules and regulations in motion picture history. - eBook - PDF

Film Manifestos and Global Cinema Cultures

A Critical Anthology

- Scott MacKenzie(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

The constraints of the Code inadvertently developed the metaphors and tropes of classical Hollywood cinema. The Code was adopted by the studios in the first instance as a means of self-censorship to avoid the possibility of state censorship. The Code was revised some eleven times between 1934 and 1961, adding provisions on crime, profanity, and cruelty to animals, among other revisions. It was rewritten in 1966, in a fairly desperate attempt to maintain relevance. This attempt did not succeed, and the Code was, for all intents and purposes, dead by 1967, after changing the face of American cinema. The Code that follows is the modified first version from 1930 that was fully implemented by the Hollywood studios in 1934. Formulated and formally adopted by The Association of Motion Picture Producers, Inc. and The Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, Inc. in March 1930 . Motion picture producers recognize the high trust and confidence which have been placed in them by the people of the world and which have made motion pictures a uni-versal form of entertainment. They recognize their responsibility to the public because of this trust and because entertainment and art are important influences in the life of a nation. Hence, though regarding motion pictures primarily as entertainment without any explicit purpose of teaching or propaganda, they know that the motion picture within its 406 • M I L I T A T I N G H O L L Y W O O D own field of entertainment may be directly responsible for spiritual or moral progress, for higher types of social life, and for much correct thinking. During the rapid transition from silent to talking pictures they have realized the neces-sity and the opportunity of subscribing to a Code to govern the production of talking pictures and of re-acknowledging this responsibility. - eBook - PDF

The Dame in the Kimono

Hollywood, Censorship, and the Production Code

- Leonard J. Leff, Jerold L. Simmons(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- The University Press of Kentucky(Publisher)

Motion pictures, according to this extraordinary docu- ment, were not the creator of standards and values but merely their mirror. As such, the box office would hold Hollywood depravity in check: moviegoers would spend their dimes on pictures they liked, shun those they did not, and, gradually, those producers who offended public decency would fade away. It was an artful defense of screen and studio freedom-and, for Hays, a magnet for more censure of the industry. The Production Code, like the counter-code, concerned morals; the adoption of either Code would concern money. Ever since Adolph Zukor had approached Kuhn, Loeb and Company for a loan to pur- chase theaters in 1919, the movie companies and the investment bank- 12 The Dame in the Kimono ers had been inseparable partners, and in the late 1920s the banks poured hundreds of thousands of dollars into the industry. The stu- dios used the cash to absorb smaller competitors, monopolize first- run outlets, and convert both production facilities and theaters to sound. As long as Hollywood turned a profit, firms like Halsey, Stuart and Kuhn, Loeb showed no desire to control picture content. In the clouded atmosphere following the October 1929 Wall Street crash, however, public protests and congressional legislation threatened the bankers' investments. Along with distributors and theater managers, the money men called for restraint, and the moguls acceded. An ad hoc commit- tee of executives worked with Hays and Lord on the final draft of the Code, polishing the prose and adding a new section labeled "Particu- lar Applications," which incorporated most of the Don'ts and Be Carefuls. Then, in February, the studio executives formally endorsed the new Production Code, and the following month the Association's Board of Directors made it Hollywood law. In March 1930, America learned about the Production Code from Variety. That Variety scooped the Motion Picture Herald stung Quigley, who blamed Hays for the leak. - eBook - ePub

Film Censorship

Regulating America's Screen

- Sheri Chinen Biesen(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- WallFlower Press(Publisher)

2ENFORCING THE Motion Picture Production CodeNotably, at the height of Hollywood screen censorship in the mid-1930s into the wartime era of the 1940s, there were several different layers of cinematic censorship to which films were subject in a complex labyrinth of censorial regulation and screen constraints: Hollywood’s official MPPDA ‘Hays Office’ Production Code Administration (PCA) film industry self-regulation which ultimately enforced its moral ‘Code’ censorship; a litany of different US state and local censorship boards, resistance and ratings scrutiny leading to threatened boycotts of ‘condemned’ films by numerous religious organisations such as the National Catholic Legion of Decency; the federal government regulation of wartime films by the Office of War Information (OWI) to further propaganda aims during World War II; and an array of international censorship agencies in different nations for exporting films overseas.The MPPDA’s ‘Hays Office’ efforts at fostering cinematic decency on Hollywood screens did encounter a few critics. By 1935, film star Marlene Dietrich criticised the Production Code and insisted, ‘Censorship is idiotic and inconsistent. Hollywood pictures today are not helped by it. The Hays Office cuts out legs but keeps in innuendos that are far worse.’68 Hard-boiled crime fiction writer James M. Cain complained, ‘I think the whole system of Hays censorship, with its effort to establish a list of rules on how to be decent is nonsensical’. He added: ‘A studio can obey every one and be salacious—violate them and be decent.’69 Cain had reason to be upset. He had the misfortune of pitching his spicy ‘red meat’ story, The Postman Always Rings Twice - eBook - ePub

Better Left Unsaid

Victorian Novels, Hays Code Films, and the Benefits of Censorship

- Nora Gilbert(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Stanford Law Books(Publisher)

by very similar rules and regulations—with very similar artistic results. These regulations were primarily moral in nature, intended to prevent the highly popular art forms of the novel and the cinema from corrupting the “susceptible” minds of their young, lower-class, and female audiences. But they were also, importantly, extralegal; Hollywood filmmakers chose to embrace the directives of the Motion Picture Production Code of 1930 (also known as the Hays Code) in order to forestall legal battles at the state and Supreme Court levels, while Victorian novelists chose to censor themselves in order to appease moral reform groups and the conservative sector of their book-buying public. Both types of artists were, then, affected not by the political censorship of tyrannical governments but by the more insidious censorship of public opinion, of middle-class morality, of the marketplace. And, in response, both sets of artists could be seen to employ comparable strategies of censorship resistance. Rather than being ruined by censorship, the novels written in nineteenth-century England and the films produced under the Production Code were stirred and stimulated by the very forces meant to restrain them.As much as I will argue what these two censorship histories have in common, one marked difference between them is the degree to which the rules of acceptability were spelled out for the artists who were expected to play by those rules. Starting in 1930 and continuing until the late 1960s, Hollywood filmmakers were provided with an ostentatiously formal list of verbal and visual requirements and prohibitions that dictated the way their films could treat everything from crime (“Revenge in modern times shall not be justified”), to sex (“Sexual perversion or any inference to it is forbidden”), to religion (“Ministers of religion should not be used as comic characters or as villains”), to particular locations (“The treatment of bedrooms must be governed by good taste and delicacy”).1 Victorian novelists received no such document. Theirs was a quieter, more intangible form of censorship, perceived by many to be all the more powerful because it went without saying. This intangibility was perhaps best described by Lord Thomas Macaulay who, in the course of writing his History of England - eBook - PDF

- Jody Pennington(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

The studios failed to meet Hays’s expectations, so he formed the Stu- dio Relations Committee in 1927 and drew up a list of “Don’ts and Be Carefuls.” Hays took the threats of boycotts from organizations such the National Congress of Parents and Teachers seriously. The studios con- tinued to worry him as well. Recognizing the ineffectualness of his list, Hays followed up on a initiative from Martin Quigley, Sr., a Catholic layman and publisher of the trade magazine Motion Picture Herald, and called upon Quigley and Daniel A. Lord, a Jesuit drama professor at St. Louis University, to draft “A Code to Govern the Making of Talking, Synchronized and Silent Motion Pictures.” Quigley and Lord composed guidelines cloaked in quasi-religious language reflecting a conservative Christian view of human sexuality and marriage. Drawing the Line 5 The Production Code reflected not only Quigley and Lord’s religious values but also their assumptions about what various censor boards and religious organizations around the country would or would not permit. Both men preferred industry self-regulation, and they wanted to prevent the emergence of new censor boards. This interested the MPPDA as well, since the web of conflicting censorship laws impeded national distribution and exhibition. To avoid confrontations with censors, the Code incorpo- rated self-censorship into the production process. The MPPDA consciously placed the Studio Relations Committee between filmmakers and the pub- lic, claiming to protect artistic freedom even while setting strict limits to expression. The Code expressed conservative beliefs about media effects that were one of the motivating factors behind calls for censorship. Motion pictures were believed capable of exerting tremendous influence on behavior, especially that of youths. Quigley and Lord were concerned that members of a film’s audience might imitate what they saw on- screen. - eBook - PDF

- Mark Paxton(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

censorship of visual and performing arts 73 motion pictures as inherently evil, found them to be providing healthy en- tertainment. 11 A coalition of nine motion picture producers agreed to submit their films to this board, which would judge them on a national standard and suggest changes to each film. 12 This national review board began in 1915. It did not, however, stop the proliferation of state and city review boards. Self-censorship through the National Board of Review was not universally ac- cepted, leading to two major changes in how movies were censored, the Hays Code and the Roman Catholic Church’s Legion of Decency. Critics called many motion pictures of the 1920s immoral and harmful to the viewing public. The Depression led to difficulties for many studios, with increases in production costs and a reduction in movie attendance from 90 million a week in 1930 to 60 million in 1933, with a corresponding re- duction in the number of theaters that were open. 13 To draw a larger audi- ence, the studios began relying on sex and violence in their films, leading to greater and greater calls for censorship. About the same time, a series of sex scandals rocked Hollywood, in particular, the suspicious death of a woman at a party hosted by obese comedian Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, 14 the death of star Wallace Reid from drugs, and the divorce and immediate remarriage of “America’s sweetheart,” Mary Pickford. 15 In the face of renewed calls for censorship of motion pictures, a number of movie studio leaders formed the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) and hired William “Will” Hays, the postmaster under President Warren Harding and chairman of the Republican National Committee, to be its public persona; 16 Joseph Breen was hired to put the new code into effect. In those roles, Hays and Breen began consolidating the local censorship rules into a national code. - eBook - ePub

- John Billheimer(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- The University Press of Kentucky(Publisher)

I The Code and the CensorsA scene from Cecil B. DeMille’s Sign of the Cross, a film that outraged the Catholic clergy and helped to establish the Legion of Decency and strengthen the Production Code. (Courtesy of Photofest.)Passage contains an image 1 Origins of the Code

The Motion Picture Production Code was a self-inflicted wound that took over thirty-four years to heal, affecting more than eleven thousand films, weakening most and leaving only a few stronger for the encounter.The origins of the Production Code were grounded in a 1915 Supreme Court decision that motion pictures were “a business pure and simple,” and thus not protected speech under the Constitution. This decision paved the way for censors at all levels, and by 1921 five states—Pennsylvania, Ohio, Maryland, Kansas, and New York—had established censorship boards to assuage growing fears that the immorality emanating from Hollywood might infect society at large. These states, which controlled nearly 30 percent of the ticket sales in the United States, had the power to ban individual films or snip selected scenes at will. They wielded this power with little oversight or consistency. Women could not smoke onscreen in Kansas, but they could in Ohio. Pregnant women could not appear on-screen in Pennsylvania, but they could in New York.1 When the New York Times asked the first chairman of New York’s Board of Censors, George H. Cobb, what principles of censorship the board followed, he replied, “So far I haven’t been able to find any.”2 - James Fenwick(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Locations: locations associated with sin or depravity (i.e. brothels).Titles: salacious, indecent, or otherwise.1The way these principles were applied varied greatly depending on the contexts of individual scripts, films, producers, studios, studio executives, and those administrators writing the report, or on how the overall plot of a project was perceived. Take the issue of sex. The Code differentiated between representing sex as a means of exciting an audience (arousal) or as being impure (love or sex that is against ‘human and divine law’) versus ‘pure love’ (Doherty 1999 , 354). The latter was permitted when showing the lawful love between a heterosexual couple (upholding the institution of marriage, for example), but it could not lead to representations of passion or lust (Doherty 1999 , 355). The Code was by its very nature contradictory and open to interpretation. The constant process of additions and revisions suggests the difficulty the PCA had in being flexible enough to ensure freedom and diversity for screenwriters and film producers, while also being focused enough to prohibit (or at the very least, discourage) topics and behaviours that were deemed morally reprehensible.These contradictions, along with the application of the Code, have largely been what has concerned scholarly inquiry into Production Code-era Hollywood. There has been a persistent research narrative focused on censorship and moral standards and the means by which the Production Code impacted and shaped the creative processes of those films that were produced. Take, for example, the work of Jane Greene (2010- eBook - PDF

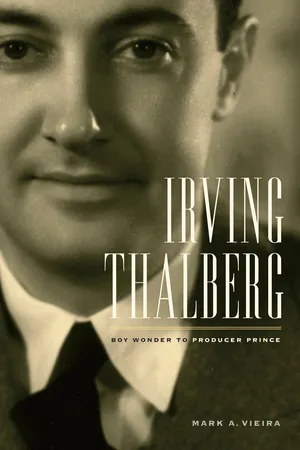

Irving Thalberg

Boy Wonder to Producer Prince

- Mark A. Vieira(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

Their document began, “No picture shall be produced which will lower the moral standards of those who see it.” To join the two documents into a cohesive code required meetings and debates. It was obvious to the Hollywood phalanx that Lord, Quigley, and the “Midwest Catholics” wanted nothing less than to arbitrate the “morality of entertainment,” forcing the studios to present a fantasy world in which there was neither sin nor conflict. Drama without conflict would not be entertainment. “We do not create these types of entertainment,” Thalberg explained in a debate on February 10. “We merely present them. The motion picture does not present the audience with tastes and manners and views and morals; it reflects those they already have. . . . The motion picture is literally bound to the mental and moral level of its vast audience.” Father Lord, not about to let Thalberg get away with this rationalization, insisted that scenes of wickedness could be shown on the screen only if the film offered “compensating moral values.” When Thalberg and Lord could not agree on how to implement this loophole, Hays adjourned the meeting and sent Lord and Quigley to work out a solution. Their “Code to Govern the Making of Silent, Synchronized and Talking Motion Pictures” was accepted by Thalberg and his peers on February 17 and ratified by the New York Board of the MPPDA on March 31. An editorial in the New York World chuckled, “That the Code will actually be applied in any sincere and thorough way, we have not the slightest belief.” In truth, T h e P r o d u c t i o n C o d e . 115 Thalberg had been cooperating with Joy and the SRC, but he saw no reason that this document should hinder his high-priced scribes. - eBook - ePub

- Jill Nelmes(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/historyonline/hollywood.cfm (accessed March 2007).Motion Picture Code (1930) http://www.artsreformation.com/a0001/hays-code.html (accessed Feb. 2007).Smith, Imogen Sara (2009) ‘Sinner’s Holiday’, Bright Lights Film Journal 63. http://www.brightlightsfilm.com/63/63precodesmith.phpThorp, Margaret (1939) America At The Movies , New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.Turan, Kenneth (1994) Los Angeles Times , Calendar Section, 31 July.–– (2003) Los Angeles Times , Calendar Section, 17 May: E9.–– (2005) Los Angeles Times , 20 May.Uncle Scoopy’s Movie House, URL: http://www.fakes.net/boxofficestats.htm (accessed March 2007)Variety Reviews, Diamond Lil , 1934, URL: http://www.mae-west.org/old/Variety (accessed March 2007).Vieira, Mark (1999) Sin in Soft Focus: PreCode Hollywood (1999) New York: Harry N. Abrams.Ward, Richard (2002) ‘Golden Age, Blue Pencils; The Hal Roach Studios and Three Cases of Censorship during Hollywood’s Studio Era’, Media History Journal 8(1) (June): 103–19.Weintraub, Joseph, ed. (1967) The Wit and Wisdom of Mae West , New York: G. P. Putnam & Sons.West, Mae (1925) SEX , Daly’s 63rd Street Theatre, produced by Main Stem Boys and Mae West, New York.––‘I’m No Angel’ , 1933, Paramount Pictures.–– (1959) Goodness has Nothing to Do with it , Prentice Hall.Passage contains an image

Chapter 4Screenwriting in Britain 1895–1929

Ian W. MacdonaldThe story of the development of screenwriting as a discrete practice is one of habitus

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.