What is the Belle Époque?

PhD, Media Arts (Royal Holloway, University of London)

Date Published: 04.11.2024,

Last Updated: 04.11.2024

Share this article

Introducing the Belle Époque

Between approximately 1871 and 1914, France experienced a perceived period of relative peace, where conflict settled, and other facets of life and society began to expand and flourish. This time is now known as the Belle Époque, translating to English as the ‘beautiful era.’ But what exactly constituted this beauty? Precipitated by the end of the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871) and the emergence of a new system of government (the French Third Republic) in 1870, the Belle Époque was characterized by a significant overhaul of social, political, and cultural tradition, resulting in a sense of optimism, confidence, and the celebration of modernity.

During this time, cities like Paris became significant cultural hubs, where radical ideas were shared and artistic expression thrived in the form of movements like expressionism, art nouveau, impressionism, and literary realism. These were indicative of the significant social changes of the time as women began to gain more independence and visibility in society, and the working classes fought for better conditions, leading to the rise of labor movements. New technologies in transport, communication, and industry lead to rapid urbanization and economic prosperity.

It is important to note that the Belle Époque was named retrospectively in the 20th century, when, during world wars and extreme unrest, a strong sense of longing for a more peaceful and prosperous time took hold. This makes it a somewhat imaginatively constructed golden age, suffused with nostalgia. Furthermore, as Diana Holmes and Carrie Tarr crucially observe,

[…] the Belle Epoque was an era when social hierarchies were loosened, and the quality of life began to improve for the mass of people. Nonetheless, the France of 1900 was very far from being a homogenous society, and any attempt to define the age must take account of the fact that in terms of material living conditions, degrees of leisure and social and spatial mobility, the lives of individuals differed radically according to class… (“Introduction,” A Belle Epoque?, 2006).

Edited by Diana Holmes and Carrie Tarr

[…] the Belle Epoque was an era when social hierarchies were loosened, and the quality of life began to improve for the mass of people. Nonetheless, the France of 1900 was very far from being a homogenous society, and any attempt to define the age must take account of the fact that in terms of material living conditions, degrees of leisure and social and spatial mobility, the lives of individuals differed radically according to class… (“Introduction,” A Belle Epoque?, 2006).

With this in mind, this study guide will explore some of the social, economic, political, technological, and cultural circumstances that contributed to the unique sense of prosperity during the Belle Époque.

Political and economic context

In 1871, France faced defeat at the hands of Germany in the Franco-Prussion War. The Treaty of Frankfurt formalized the end of hostilities, which resulted in significant territorial losses for France. This year also witnessed the Paris Commune, a revolutionary movement that seized Paris between March 18th and May 28th. In response to the failures of the national government and frustration with economic hardship, the working classes sought to establish a more democratic and socialist society. This uprising was ultimately quashed, solidifying the power of the conservative Third Republic. (For more on this, see Carolyn J. Eichner’s The Paris Commune). Following the turmoil of the Paris Commune, the Third Republic worked to stabilize the nation politically and economically, fostering a burgeoning middle class with disposable income. This was followed by a period of relative harmony and stability in France.

Also notable during this period was France’s colonial expansion. Holmes and Tarr assert that “between 1880 and 1895 the size of the French colonial empire grew from one to 9.5 million square kilometres” (2006). This included the consolidation and growth of French colonial territories in Africa, Asia, and the Pacific. By the early 20th century, France had constructed one of the largest empires in the world, promoting ideas of French culture as the height of civilization. This all amounted to a surge of French nationalism and cultural activity. It was on this foundation that the Belle Époque was built, the result of significant societal shifts. (For more on French colonialism, see Vestiges of Colonial Empire in France by Robert Aldrich.)

But the Belle Époque embodied a contradiction. It was a time of cultural self-expression, but also saw the repression of socialist ideas following the Paris Commune. It was a time of economic prosperity, yet wealth disparity prompted strikes and unionizations among working-class industries. As Pierre Goubert puts it in The Course of French History, “The atmosphere of the Belle Epoque was marked by diverse or even contradictory moods” (2002).

Ultimately, while the Belle Époque is often remembered as a period of profound cultural flourishing, it was set against a backdrop of complex political dynamics and tension that foreshadowed the impending conflicts of World War I.

Social life

The Belle Époque saw many societal shifts, with changing gender and class dynamics. The emergence of a newly formed middle class, known as the bourgeoisie, complicated previously existing class distinctions. With their disposable income, the bourgeoisie became patrons of the arts, driving up demand for leisure and entertainment.

Like many prosperous eras in modern history, this new demand could be seen in the thriving nightlife and drinking culture that reflected the period’s cultural dynamism and social changes. Intellectuals, artists, and writers would meet in cafes, bars, and bistros to discuss new ideas, while dancing and drinking would take place at cabarets and music and dance halls. One example of such an establishment was the Moulin Rouge, famously depicted in Baz Luhrmann’s 2001 movie by the same name. See the trailer below, for a look into a modern depiction of the Belle Époque nightlife:

"Moulin Rouge | #TBT Trailer," 20th Century Studios, [2015]

Popular activities and gatherings like these fostered a sense of freedom and expression that permeated the cultural moment.

The era also marked the beginnings of the women’s rights movement, as women advocated for suffrage (i.e., the right to vote) and greater social freedoms, gradually entering the workforce in sectors like education and healthcare. This challenged traditional family structures, expanding women’s roles and acknowledging their achievements beyond motherhood and homemaking. This turn of the century feminism heralded a new model of womanhood. (For more on this, see our study guide “Waves of Feminism - First to Fourth Wave Timeline”).

In Having It All in the Belle Epoque, Rachel Mesch describes the burgeoning feminist movement in France, noting,

French feminism was forcefully emerging while still struggling to define itself […] in the 1890s and early 1900s, feminists took up a wide variety of causes in France, including the rights of women workers, poor women and prostitutes; infant mortality; changes to the French civil code; and, eventually, suffrage. (2013)

Rachel Mesch

French feminism was forcefully emerging while still struggling to define itself […] in the 1890s and early 1900s, feminists took up a wide variety of causes in France, including the rights of women workers, poor women and prostitutes; infant mortality; changes to the French civil code; and, eventually, suffrage. (2013)

With the call for women’s rights and freedoms gaining momentum, images of what the new, modern woman might look like hit the mainstream. Depictions of women in bars, dancing, smoking cigarettes, or riding bicycles and wearing trousers – in contexts of workplaces and pleasurable activities – were circulated in artwork, literature, and popular culture. One example of this is the work of famous poster artist, Léonetto Cappiello (1875–1942) (see Figure 1.)

Fig 1. Cappiello, L. (c.1900), Cycles Omega (Picryl)

These are just some of the ways in which social dynamics were reshaped during the Belle Époque. New class structures enhanced cultural engagement and a shift in lifestyle associating the era with a lasting sense of progress and optimism.

Artistic movements

Social freedom was further represented in the art of the Belle Époque, which hosted a myriad of experimental movements that would change aesthetic values and standards forever.

Impressionism

Impressionism, led by artists like Claude Monet (1840–1926), Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), Edgar Degas (1834-1917), and Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) was an example of a movement that emerged during the Belle Époque. Impressionist subject matter often depicted busy modern life, such as scenes of bustling cafés and leisure activities in parks. A fascination with trips to the country and long picnics also occupied impressionist works, illustrating the activities of the bourgeoisie. Stylistically, the swift brush strokes and distinct use of light reflected the changing technologies, the quickening pace of travel, and the scientific advancements of the time. As Nathalia Brodskaïa asserts, this indicated a time when impressionists took “steps away from neo-classical painting and moved closer to modern life” (Impressionism, 2014). (To learn more, read our guide “What is Impressionism?”)

Monet’s Water Lilies, (or Nymphéas in French) exemplifies this impressionist style, with its noticeable brush strokes and sense of light evoking movement and fluidity (see Figure 2).

Fig 2. Monet, C. (1905), Nymphéas (posted by G. Starke, Flickr, [2018])

Art nouveau

Another significant movement of the time was art nouveau. Art nouveau challenged the technological and industrial advancements of the late 1800s and the art movements that earlier dominated the century, depicting the whimsical shapes of nature in unexpected, asymmetrical ways. It was lavish, celebratory, and sometimes abstract, reinstating a harmony between humans and the natural world.

Expressionism

At the beginning of the 20th century, expressionism rose to artistic prominence, with its dark, tumultuous exploration of individualism. Artists like Georges Rouault (1871–1857), Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), and Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) provided a counter-narrative to the celebratory tone of the Belle Époque, exhibiting ideas of existentially anxiety, emotion, and isolation in the wake of dehumanizing modernity.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

But not all works of art made during the Belle Époque fell neatly into a particular artistic movement. For example, French painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901) was highly indicative of the time, depicting vibrant Parisian nightlife scenes that sought to highlight marginalized people, including sex workers, performers, and the working class. Grose Evans traces Toulouse-Lautrec’s artistic development, explaining

In 1885 he turned his back upon the academic style and, taking hints from the free brushwork of the Impressionists and from Japanese designs, Lautrec began to paint his pictures of Parisian night life, circus performers, and cabaret entertainers. (French Painting of the 19th Century in the National Gallery of Art, 1959, [2019])

Grose Evans

In 1885 he turned his back upon the academic style and, taking hints from the free brushwork of the Impressionists and from Japanese designs, Lautrec began to paint his pictures of Parisian night life, circus performers, and cabaret entertainers. (French Painting of the 19th Century in the National Gallery of Art, 1959, [2019])

The Japanese influence on Toulouse-Lautrec’s work indicates the expansion of cultural exchanges during the Belle Époque, and his post-impressionist style made his paintings pivotal in the development of modern art. His paintings are at once colourful, energetic and full of empathy for his subjects, making them symbolic of the era. (For an example, see Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s At the Moulin Rouge, 1892, Art Institute Chicago.)

Pierre-Victor Galland

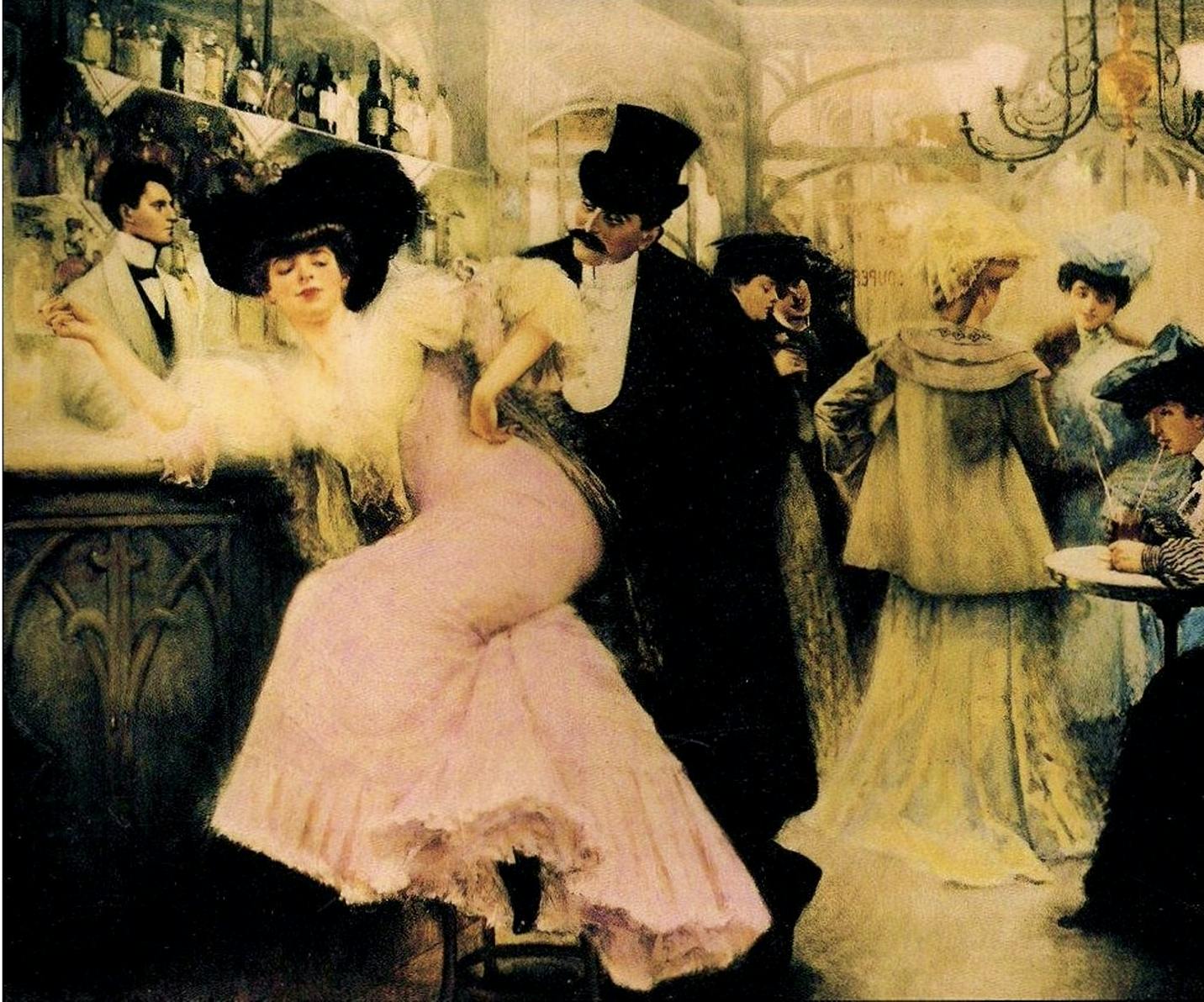

Another artist who has become synonymous with the Belle Epoque is Pierre-Victor Galland (1822–1894), particularly his painting Le bar de Maxim's (c. 1890) (see Figure 3). While relatively little is now known about this painting, its romantic exploration of leisure, bar culture, and social dynamics has made it indicative of its time.

Fig 3. Galland, P-V. (c.1890) Le bar de Maxim's (Wikimedia Commons)

Le bar de Maxim's depicts the elegant interior of one of Paris’ most significant restaurants and cabarets of the time. It shows a woman, dressed in the heights of fashion, as she is approached by an equally well-dressed man. The nature of their relationship is ambiguous but their dynamic, set against the indulgent opulence of the bar, is in part what makes this piece of work so important. Through the subject’s clothing and activity, this female representation subverts traditional roles of women, instead imbuing the subject with social agency, independence, and emotion, indicating a changing attitude towards women in society. Galland’s use of colour and light highlights the complexity and indulgence of modern life, making the work a typical celebration of the Belle Époque.

These are just a few examples of the flurry of artistic activity that took place during the period, celebrating and challenging the cultural and social changes of the time. Each movement and work of art contributed uniquely to the exploration of new ideas and forms, paving the way for the modern art of the 20th century.

Philosophies and literature

The Belle Époque saw a surge of new thoughts and ideas, reflected in philosophical movements not only in France but across Europe. The philosophies and literature that emerged at this time reflected the period's cultural and social changes, as thinkers grappled with modernity, science, and individualism.

Analytic thinkers like Henri Bergson (1859–1941) emphasized the importance of intuition and subjective experience over rationalism. In contrast, positivism – another significant development in philosophy of the time – championed scientific method and empirical evidence as the basis of all knowledge. Crucially, Nietzschean nihilism had emerged at this time, with Friedrich Nietzsche’s (1844–1900) writings claiming that “‘God is dead”’ and that a superman must rise up in his place (Thus Spoke Zarathustra, 1883, [2017]). These ideas indicated the overturning of divine authority and the agency of individuals when it comes to principles and values.

As a result, intellectual movements such as existentialism began to take shape, with Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980) ultimately asserting that “existence preceded essence’ (Being and Nothingness, 1943, [2021]). This was a philosophical transformation of the older view that the essence (or nature) of a thing was fixed and took precedence over its fact of being. Instead, existentialism claimed that individuals have no predetermined essence and self-determine through the freedom of choice and action. This sentiment was also explored by Simone de Beauvoir (1908–1986) who applied existential thought to gender, society, and the process of ‘becoming’ a woman (The Second Sex, 1949).

In literature, writers tackled similar ideas with authors such as Marcel Proust (1871–1922) and André Gide (1869–1951) exploring themes of identity, human emotion, and the workings of the mind. On one hand, often breaking from traditional narrative forms, writers began playing with streams of consciousness and experimenting with perception. Symbolism and impressionism in poetry and prose reflected a shift towards this individual perception, prioritizing subjectivity. On the other, realism and naturalism also emerged. Writers such as Émile Zola (1840–1902)and Guy de Maupassant (1850–1893) focused on realistic portrayals of everyday life and the human psyche, often examining the struggles of the working class and the effects of industrialization.

Philosophy and literature during the Belle Époque were varied, often questioning traditional value systems and critiquing human obedience to authority or higher powers. This overhaul of philosophical values provoked the Belle Époque as a period of intellectual enlightenment.

The end of the Belle Époque

The Belle Époque is largely accepted to have come to an end with the start of World War I. The period that was characterized by opulence, leisure, and cultural abundance could not withstand the imminence of war. The conflict ultimately shattered the illusion of stability and progress, leading to widespread despondency. In Years of Plenty, Years of Want, Benjamin Franklin Martin observes,

Without question, France was profoundly wounded by the experience of the Great War and never recovered fully during the 1920s and 1930s. Even calling the prewar period la Belle Epoque (the “good old days”) implied that the best times in France were gone. (2013)

Benjamin Franklin Martin

Without question, France was profoundly wounded by the experience of the Great War and never recovered fully during the 1920s and 1930s. Even calling the prewar period la Belle Epoque (the “good old days”) implied that the best times in France were gone. (2013)

With resources and the labour force reallocated to the front lines, the spirit of the Belle Époque is seen to have quickly been extinguished. In the years during the war, the period would be looked back on with significant fondness for what was lost. With the nostalgia for a more peaceful time, the picture of Belle Époque began to come into focus as a moment in history where creativity and intellect flourished and monumental social and cultural progress took place.

Further reading on Perlego

Nineteenth-Century Europe (2018) by M. Rapport

The Hypocrisy of Justice in the Belle Epoque (1999) B. Martin

Illuminated Paris (2019) H. Clayson

The Art of Pleasure (2022) Hans-Jürgen Döpp

Belle Époque FAQs

What is the Belle Époque in simple terms?

What is the Belle Époque in simple terms?

What was the historical context of the Belle Époque?

What was the historical context of the Belle Époque?

What were some examples of artistic movements during the Belle Époque?

What were some examples of artistic movements during the Belle Époque?

How did the Belle Époque end?

How did the Belle Époque end?

Bibliography

Aldrich, R. (2004) Vestiges of Colonial Empire in France. Palgrave Macmillan. Available at:

https://www.perlego.com/book/3479337/vestiges-of-colonial-empire-in-france

Brodskaïa, N. (2014) Impressionism. Parkstone International. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3733624

de Beauvoir, S. (2015) The Second Sex. Penguin. Available at:

https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/360348/the-second-sex-by-simone-de-beauvoir/9780099595731

Eichner, C. J. (2022) The Paris Commune: A Brief History. Rutger's University Press. Available at:

https://www.perlego.com/book/3865305/the-paris-commune-a-brief-history

Evans, G. (2019) French Painting of the 19th Century in the National Gallery of Art. Perlego. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1820370

Goubert, P. (2002) The Course of French History. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1618454

Holmes, D. and Tarr, C. (eds) (2006) A Belle Epoque? Women and Feminism in French Society and Culture 1890-1914. 1st edn. Berghahn Books. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/541247

Martin, B. F. (2013) Years of Plenty, Years of Want: France and the Legacy of the Great War. Northern Illinois University Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1039016

Mesch, R. (2013) Having It All in the Belle Epoque: How French Women's Magazines Invented the Modern Woman. Stanford University Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/745232

Nietzsche, F. (2017) Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Re-Image Publishing. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1885844

Sartre, J.-P. and Richmond, S. (2021) Being and Nothingness. Atria Books. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2823731

Artwork

Cappiello, L. (c.1900) Cycles Omega [Lithography] (Uploaded on Picryl)

Monet, C. (1905), Nymphéas [Oil on canvas]. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. (Posted by G. Starke, Flickr, 2018)

Galland, P-V. (c.1890), Le bar de Maxim's (Uploaded on Wikimedia Commons)

PhD, Media Arts (Royal Holloway, University of London)

Aoiffe Walsh has a PhD in Media Arts from Royal Holloway, University of London. With a background in film studies and philosophy, her current research explores British literary modernism, with a particular focus on surrealism between the wars. She has lectured and published pieces on documentary and film theory, film history, genre studies and the avant-garde.