What was the Berlin Wall?

PhD, English Literature (Lancaster University)

Date Published: 26.11.2024,

Last Updated: 09.12.2024

Share this article

Introduction

On the morning of August 13, 1961, the citizens of Berlin awoke to a wall, made of barbed wire and cinder blocks, separating East and West Berlin. East Berliners were prevented from crossing over to the West. Families and friends were separated, some of whom would never reunite. A Guardian report in 2014 compiled first-hand accounts from those on both sides of the Wall:

“We began to hear people outside yelling, crying, louder and louder. We went into the street to witness tragic panic and fear. Neighbours were telling each other (and us) that they had relatives in East Berlin – they had tried to contact them, but couldn’t – that no one knew what was happening. [...] I had never witnessed anything like this. Everyone cried. As time went on, neighbours told us they thought their loved ones behind the wall were lost to them for good … I’m sure some of those ‘lost’ relations died over that period. That night is etched in my permanent memory.” (Barb Dignan, quoted in Caroline Bannock, “Berlin Wall – readers' memories,” The Guardian)

The Berlin Wall was a powerful symbol of the Iron Curtain, the ideological and physical division of the communist and non-communist world following WWII. It would remain standing until 1989. As Manfred Wilke writes in The Path to the Berlin Wall (2014),

The Berlin Wall was a multifaceted, concrete border. It split the city in two, forming part of both the inner-German division and the cleft between the Soviet Empire and the Western European democracies. After its construction in 1961, the Wall came to symbolize the division of Germany and the oppositional forces of dictatorship and freedom; internationally, it remained the most indelible image of the Cold War.

Manfred Wilke

The Berlin Wall was a multifaceted, concrete border. It split the city in two, forming part of both the inner-German division and the cleft between the Soviet Empire and the Western European democracies. After its construction in 1961, the Wall came to symbolize the division of Germany and the oppositional forces of dictatorship and freedom; internationally, it remained the most indelible image of the Cold War.

In this study guide, we will explore why the Berlin Wall was built, and the reactions to it, as well as delve into life behind the Wall and the circumstances that led to its eventual fall.

Background: Post-WWII division of Germany

Following Germany’s defeat in WWII, and the Potsdam Conference in 1945, the Allied powers (Great Britain, the United States, France, and the Soviet Union) divided Germany into four zones: Britain occupied the northwest, France the southwest, the US the south, and the Soviet Union took the east:

As the Soviet empire grew into the post–World War II USSR, East Germany became a country within that Communist coalition. The former Germany became two Germanies: East and West, Communist and democratic. Ironically to those living in democratic societies, Communist East Germany was known as the German Democratic Republic, or GDR, and was officially so founded and named in 1949 by the Soviet leadership that would hold sway over the country until the wall came down and eastern Communism fell apart under its own weight. (Jim Willis, Daily Life Behind the Iron Curtain, 2013)

Jim Willis

As the Soviet empire grew into the post–World War II USSR, East Germany became a country within that Communist coalition. The former Germany became two Germanies: East and West, Communist and democratic. Ironically to those living in democratic societies, Communist East Germany was known as the German Democratic Republic, or GDR, and was officially so founded and named in 1949 by the Soviet leadership that would hold sway over the country until the wall came down and eastern Communism fell apart under its own weight. (Jim Willis, Daily Life Behind the Iron Curtain, 2013)

Around 2.7 million citizens emigrated from East to West Germany between 1949 and 1961; this posed a major challenge to the continued existence of the GDR as many skilled laborers were being lost to West Berlin:

Fewer and fewer skilled workers remained in the East, where the exodus exacerbated economic hardship. The Russians sold more than fifty tons of gold to prop up their tottering East German satellite, but no amount of cash could slow the tide of émigrés. (David Frye, Walls, 2018)

David Frye

Fewer and fewer skilled workers remained in the East, where the exodus exacerbated economic hardship. The Russians sold more than fifty tons of gold to prop up their tottering East German satellite, but no amount of cash could slow the tide of émigrés. (David Frye, Walls, 2018)

It is worth noting, however, that there was also resistance to West Germany, or the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG)(ruled by the Western Allies), as indicated by the militant far-left group the Red Army Faction (RAF) (also known as the Baader-Meinhof Gang) that was founded in 1970. In addition, the student-led group, the New Left, protested against the FRG which it found to have made insufficient attempts at denazification and saw as an extension of US imperialism. To learn more, see Jeremy Varon’s Bringing the War Home (2004), Philipp Gassert and Alan E. Steinweis’ edited collection Coping with the Nazi Past (2006), and Francis Graham-Dixon’s The Allied Occupation of Germany (2016).

Despite these grievances with the FRG, many in East Germany did not want to live under Soviet rule. It became clear that should migration to the West continue, the GDR would collapse. At the Vienna Summit in June 1961, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev insisted that the US relinquish West Berlin to the control of the GDR, which President John F. Kennedy refused. In response, East Germany passed a decree on August 12 that a wall would be built to close off East German access to West Germany.

August 1961: The Wall goes up

The day the construction began on the Wall, Sunday 13 August 1961, is referred to as “Barbed Wire Sunday”. As Gordon L. Rottman explains,

[...] West Berlin was awakened by the sounds of trucks, tractors, cranes, military vehicles, and marching troops. The West was taken entirely by surprise as 20,000 armed troops moved into position surrounding the city beginning at 2 a.m. Kilometres-long columns of vehicles streamed in from all over the DDR. The troops did not know what was happening until they reached their posts. It was a well-planned operation involving much of the East German uniformed forces, the People’s Police, Frontier Police and Worker’s Militia plus Soviet troops. Even girls of youth organizations served food to the troops and labourers. Construction materials and heavy equipment had also been secretly prepared. (The Berlin Wall and the Intra-German Border 1961-89, 2012)

Gordon L. Rottman

[...] West Berlin was awakened by the sounds of trucks, tractors, cranes, military vehicles, and marching troops. The West was taken entirely by surprise as 20,000 armed troops moved into position surrounding the city beginning at 2 a.m. Kilometres-long columns of vehicles streamed in from all over the DDR. The troops did not know what was happening until they reached their posts. It was a well-planned operation involving much of the East German uniformed forces, the People’s Police, Frontier Police and Worker’s Militia plus Soviet troops. Even girls of youth organizations served food to the troops and labourers. Construction materials and heavy equipment had also been secretly prepared. (The Berlin Wall and the Intra-German Border 1961-89, 2012)

In the clip below, you can see footage of the Wall being built as correspondent Nigel Ryan reports on the scenes 10 days after construction began:

“Rare Footage of East German Troops Building the Berlin Wall (1961),” ITN Archive, [2022]

The first walls were made of barbed wire, bricks, and cinder blocks and “were rapidly replaced with prefab concrete slabs, blocks and beams. The workmanship was crude, with speed being the major concern” (Rottman, 2012). The Berlin Wall stood at around four meters tall and 155 kilometres long and was heavily guarded by the “death strip” a piece of land which contained mines and, by 1989, had 302 watchtowers (“The Wall in Numbers,” Berlin.de). The map in Figure 1 below details where the Wall was placed and the various checkpoints.

Fig. 1. “Berlin Wall Map,” (Created by ChrisO, 2005) Wikimedia Commons

As Willis writes,

When the Wall was finished many years later, the forbidding Monster, as it came to be known, would divide the two Berlins, virtually encircling West Berlin along the border created by post–World War II negotiations. The Wall included guard towers atop the concrete structure that circumscribed a swath of no man’s land often called the death strip, which contained antivehicle defenses. A “baby wall” was built on the eastern edge of this death strip. Defection came to a standstill among East Germans wanting to flee. In the months and years ahead, many brave souls would try; many would fail and lose their lives in the process. (2013)

Reactions and protests to the Wall

The initial reaction to the Wall was one of shock and grief:

The first days of division were marked by heartbreaking scenes of families and friends who had been separated overnight by barbed wire and the first sections of the Wall. East Berliners who worked in the western sectors were cut off from their jobs. Neighborhoods were split. [...]The Western powers, caught off guard by the East German action, had no immediate response. US president John F. Kennedy, informed of the developments while he was vacationing, remarked, “It’s not a very nice solution, but a wall is a hell of a lot better than a war.” (Reinhard Zachau and Richard Apgar, Hidden Berlin, 2022)

Reinhard Zachau and Richard Apgar

The first days of division were marked by heartbreaking scenes of families and friends who had been separated overnight by barbed wire and the first sections of the Wall. East Berliners who worked in the western sectors were cut off from their jobs. Neighborhoods were split. [...]The Western powers, caught off guard by the East German action, had no immediate response. US president John F. Kennedy, informed of the developments while he was vacationing, remarked, “It’s not a very nice solution, but a wall is a hell of a lot better than a war.” (Reinhard Zachau and Richard Apgar, Hidden Berlin, 2022)

The Berlin Wall attracted much resistance from citizens on either side with angry protestors gathering at the Wall, with many trying to physically dismantle it. The GDR responded quickly to these initial protests by sending in more troops and reinforcing border barricades, proclaiming the Anti-Fascist Protection Wall was to protect the state from the influence of Western capitalism.

Protests, however, continued with anger directed at both the GDR and other global leaders:

Hundreds of thousands of West Berliners attended night protest rallies, and targeted some of their anger at the Western Allies’ passive response. The USA protested to the Soviets, but could do little as West Berlin itself was under no direct threat and the essentials of the Potsdam Agreement were not being violated – namely the presence of Allied troops, free access to East Berlin by the Western Allies, and the right of self-determination of West Berliners. (Rottman, 2012)

Art as protest

Protests took many forms, and in the 1980s West Berliners began graffitiing their side of the Wall. Artist Thierry Noir, the first to graffiti the Wall, reflects upon his motivations:

“We are not trying to make the wall beautiful because in fact it’s absolutely impossible. 80 persons have been killed trying to jump over the Berlin wall, to escape to west-Berlin, so you can cover that wall with hundred of kilos of color, it will stay the same.” (“The Berlin Wall,” Noir, [2024])

One example of Noir’s work is “Red Dope on Rabbits,” painted at Potsdamer Platz in August 1985, which was dedicated to the wild rabbits that lived on the “death strip” between the two sides of the Wall:

“Those rabbits were a mutation of nature. Where else would you see so many rabbits running around freely in the middle of a big city? The only place was in divided Berlin.” (Noir, Noir, [2024])

The painting of the Wall continued after its fall, with one of the most famous examples being Dmitri Vrubel’s 1990 mural “My God, Help Me to Survive This Deadly Love” (Figure 2), which depicted Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev kissing East German leader Erich Honecker.

Fig 2. “Berlino Muro, 02” (Photographed by Angelo Faiazza, 2014) Wikimedia Commons

For more on Berlin Wall graffiti, see Claudia Mesch’s Modern Art and the Berlin Wall (2009).

Escape attempts

The fortifications and looming presence of the Wall were not enough to stop the escape attempts:

Ground-floor building windows facing the West were bricked up to prevent escape. However, escapees would use upper windows, dropping notes to the West Berlin police below who would arrange for fire crews to come with nets to catch jumpers. As a result, the upper windows were then bricked up as well. (Rottman, 2012)

The armed soldiers at the border were given the order to shoot anyone trying to cross the Wall if they were unable to apprehend them otherwise. Many Germans were killed attempting to cross over into West Germany; between 1961 and 1989, at least 140 people were shot at the border, and 91 of these were shot by soldiers when they were attempting to flee (“Victims of the Wall,” Berlin.de). The order to shoot was not lifted until April 1989.

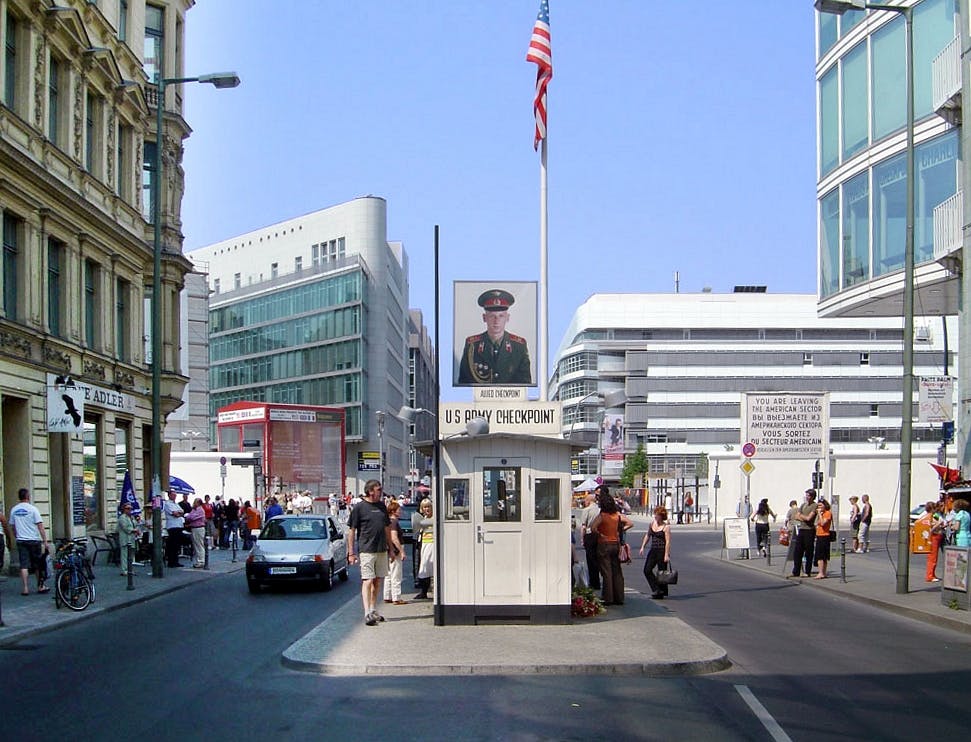

One major site of escape attempts was Checkpoint Charlie, a crossing point between East and West Berlin and a symbol of the Cold War (see Figure 3) where military and diplomatic personnel could cross over into East Berlin.

Fig. 3. “Checkpoint Charlie,” Wikimedia Commons

The checkpoint was torn down after the German reunification, and a replica was constructed at the site. This tourist attraction stands next to the Museum House at Checkpoint Charlie, where visitors can learn more about the checkpoint and escape attempts at the site.

Life behind the Berlin Wall

Familial separation

As previously mentioned, when the Wall went up, many families were separated from each other for decades, and some would never reunite. Among these tragic stories is that of Sigrid Paul, a citizen of the GDR, who was separated from her baby for four years due to the Wall. In 1961, Paul’s infant son, Torsten, was taken ill and needed to go to the West for medication, which, of course, was not permitted. Doctors in East Berlin, unbeknown to Paul, forged Torsten’s documents and transferred him to the West for essential care:

"Every day I went from one authority to another to try to get permission to see him, even for an hour or two," she says. "It was futile. Every application was rejected. The uncertainty about whether we would see Torsten again was unbearable." (Lena Corner, “The Berlin Wall kept me apart from my baby son,” The Guardian, 2009)

This is but one of thousands of stories of German citizens being forcibly separated from their loved ones.

In the initial years, no citizens of East Berlin or East Germany were permitted to travel to the West at all; not even into West Berlin itself. Some exceptions to this included:

- Elderly retirees, who could move to West Germany from 1965

- Visits to relatives for important family matters

- People traveling to the West for work

- Day passes or shopping trips (family members needed to remain behind to ensure the citizen’s return)

However, East Germans still needed to apply for visas regardless of any exceptions and approval was not guaranteed.

Psychological impact: Wall sickness

The Wall caused significant psychological distress as East Berlin citizens found themselves suddenly sealed off from the rest of the world. Some even began to experience what became known as “Wall sickness”:

The prominent East German psychiatrist Dietfried Müller-Hegemann, who fled to the west in 1971, found that the sudden impact of the Wall violated expectations of normality. His patients reacted directly to the impact of the Wall’s appearance, and the sudden imposition on mobility contributed to psychological ailments that were often expressed through physical symptoms. The term Wall or Mauer was strictly forbidden in the East where the term border was deemed more appropriate, denying the inhabitants a vernacular turn of phrase that may have reminded them of the absurdity of the structure. (Donna West Brett, Photography and Place, 2016)

Donna West Brett

The prominent East German psychiatrist Dietfried Müller-Hegemann, who fled to the west in 1971, found that the sudden impact of the Wall violated expectations of normality. His patients reacted directly to the impact of the Wall’s appearance, and the sudden imposition on mobility contributed to psychological ailments that were often expressed through physical symptoms. The term Wall or Mauer was strictly forbidden in the East where the term border was deemed more appropriate, denying the inhabitants a vernacular turn of phrase that may have reminded them of the absurdity of the structure. (Donna West Brett, Photography and Place, 2016)

In “The Berlin Wall sickness that still lingers today,” Stephen Evans interviews Gitta Heinrich, who lived next to the Berlin Wall in the village of Klein-Glienicke and suffers from wall sickness:

Even today Gitta Heinrich doesn't have walls around her home in Berlin. Her fences are made of trees and bushes rather than bricks. Inside, she keeps the doors open between rooms. She avoids confined spaces with crowds of people."The whole village was like a prison", she says today. "Wherever you went, you had to see the Wall." When the Wall came down, she went to see a doctor because she felt anxious and uneasy. The doctor told her she had Wall sickness. "It was an illness with a deep impact on the psyche," she says. "It was this real feeling of narrowness." (BBC, 2011)

The Stasi

East Berlin’s state security, the Stasi (short for Staatssicherheitsdienst, or Ministry of State Security) monitored the activity of citizens they suspected were spies or were a threat to the state. As Willis explains,

The Stasi was the most dreaded aspect of life in East Germany for most people living there. The organization infiltrated many other groups, associations, and even churches, always looking for those individuals deemed disloyal to the state or the Communist Party. (2013)

More than 200,000 East Germans were imprisoned by the Stasi during the Cold War, mainly for attempting to flee to the West.

The Stasi was “triple the size of Adolf Hitler’s infamous Gestapo,” as Willis writes, however, their methods were more covert (2013). Though the Stasi did indeed imprison and execute citizens, it typically “exerted more of a psychological set of restraints” than the Gestapo or KGB (Willis, 2013). It relied upon an extensive network of informants to repress and monitor citizens, threatening, blackmailing, and bribing citizens to spy upon their family members, friends, and colleagues. As Barbara Miller explains,

in the minds of the East German population, the Stasi functioned as though it were physically omnipresent, and many a conversation was subjected to a form of self-imposed censorship in the belief that it was being furtively recorded and analysed. (The Stasi Files Unveiled, 2022)

Barbara Miller

in the minds of the East German population, the Stasi functioned as though it were physically omnipresent, and many a conversation was subjected to a form of self-imposed censorship in the belief that it was being furtively recorded and analysed. (The Stasi Files Unveiled, 2022)

Ultimately, life in East Germany was one largely characterized by restriction and surveillance. Though many East Berliners became accustomed to life under the GDR, as Willis writes, the curtailing of its citizens’ personal freedom would be the downfall of Soviet-controlled Germany:

For most, [life under European Communism] was comprised of learning the rules; accepting the subsidies, education, and jobs the government often provided; and not expecting much more. Personal ambitions were held in check, presumably for the good of the larger group. [...] Life falls into a familiar pattern in any society, and so it did for many in Soviet-controlled countries as well. After a time, the familiar becomes home, and many don’t want to leave those familiar surroundings and culture they have grown accustomed to. [...] No one likes to be caged, even in a large cage, nor told what to do or that their aspirations and dreams are too big and cannot be realized. (Willis, 2013)

It is worth noting, however, that life under the GDR was not a completely negative experience for all East German citizens. For example, those in East Germany, overall, experienced greater gender equality and were provided with numerous social benefits. To learn more on this, see our guide "What was the German Democratic Republic (GDR)?"

The fall of the Berlin Wall

In 1989, a changing political landscape, increased applications for visas, and civil unrest pressured the GDR to relax some of its travel restrictions to West Germany. In November 1989, GDR authorities were receiving an increasing number of applications for exit visas, and a demonstration of a million people in Berlin on November 4 resulted in the GDR being “forced to pass new freedom of movement laws” (50 Minutes, The Fall of the Berlin Wall, 2017).

On November 9 1989, a spokesperson for the East German Politburo (the policymaking committee for the communist party), Günter Schabowski announced at a press conference that East Germans were able to now travel to West Germany, failing to state that some restrictions would remain. At the press conference, Schabowski had reported that all East Germans would be allowed to have a passport for the first time. A reporter asked when this would take effect, to which Schabowski shrugged and replied “Ab Sofort” (“from now”):

In fact, this was not at all what the regime had in mind. Yes, East Germans would be granted passports. Yes, they would be allowed to travel. But to use them, they would first have to apply for an exit visa, subject to the usual rules and regulations. And the fine print said they could do that only on the next day, November 10. Certainly, the last thing [GDR leader Egon] Krenz intended was for his citizens to just get up and go. But East Germans didn’t know that. They only knew what they heard on TV, which circulated like wildfire through the city. Thanks to Schabowski, they thought they were free. Sofort. By the tens of thousands they flocked to the crossing points to the West. Strangely oblivious to the earthquake his words had caused, Schabowski headed home for dinner. (Michael Meyer, 1989: The Year that Changed the World, 2010).

Michael Meyer

In fact, this was not at all what the regime had in mind. Yes, East Germans would be granted passports. Yes, they would be allowed to travel. But to use them, they would first have to apply for an exit visa, subject to the usual rules and regulations. And the fine print said they could do that only on the next day, November 10. Certainly, the last thing [GDR leader Egon] Krenz intended was for his citizens to just get up and go. But East Germans didn’t know that. They only knew what they heard on TV, which circulated like wildfire through the city. Thanks to Schabowski, they thought they were free. Sofort. By the tens of thousands they flocked to the crossing points to the West. Strangely oblivious to the earthquake his words had caused, Schabowski headed home for dinner. (Michael Meyer, 1989: The Year that Changed the World, 2010).

The West German media reported that the Wall had been opened, resulting in Berliners converging at the border posts in the hundreds of thousands. To avoid bloodshed, and with senior officials incommunicado, the guards opened the gates at 11.30 pm. Berliners began tearing down the symbol of oppression and division that had stood for 28 years:

The image of thousands of German citizens standing on the wall with chisels and hammers in hand, striking a blow against the large, gray, once imposing structure, is still one of the most enduring images of our time. (Peter Schweizer, “The Fall of the Berlin Wall after Ten Years,”The Fall of the Berlin Wall, 2019)

Edited by Peter Schweizer

The image of thousands of German citizens standing on the wall with chisels and hammers in hand, striking a blow against the large, gray, once imposing structure, is still one of the most enduring images of our time. (Peter Schweizer, “The Fall of the Berlin Wall after Ten Years,”The Fall of the Berlin Wall, 2019)

The clip below shows the celebrations on the west side of the Wall the evening after the border opened, capturing the excitement at the closing of this chapter of German history:

"1989: The Berlin Wall falls," CNN, [2010]

The fall of the Berlin Wall resulted in the weakening of the GDR and the eventual reunification of Germany in October 1990 when it was absorbed into the Federal Republic of Germany:

The GDR had ceased to be, and in the following years the question of how to confront its legacy would become the subject of bitter controversy between and within the two former Germanys. (Barbara Miller, Narratives of Guilt and Compliance in Unified Germany, 2002)

Barbara Miller

The GDR had ceased to be, and in the following years the question of how to confront its legacy would become the subject of bitter controversy between and within the two former Germanys. (Barbara Miller, Narratives of Guilt and Compliance in Unified Germany, 2002)

For more on the German reunification, see Frédéric Bozo, Andreas Rödder, and Mary Elise Sarotte’s edited collection German Reunification (2016).

Legacy

Once the Wall came down, the space it occupied was repurposed for new buildings, communal spaces, and memorials, such as the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe and the Berlin Wall Memorial. The East Side Gallery and Checkpoint Charlie also remain key tourist sites, attracting approximately three million and four million visitors each year, respectively.

November 2024 marks the 35th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, an event which symbolized the end of the Cold War and ultimately, reshaped the political landscape of postwar Europe. Though the Wall is long gone, its lasting psychological impact on German citizens cannot be understated, from Wall Sickness to the difficulties in merging two distinct German identities:

However you viewed it, The Wall made the city not just unique but completely abnormal. [...] Nobody knew how much the forty years had moulded East and West in separate ways, or even whether there was still a common German identity [...] Quietly in the background, hesitantly, carrying inescapable prejudices and preconceptions, the citizens of the two Germanys reached towards each other. Far from immediate satisfaction for the unleashed desires, ordinary people began to speak of it lasting generations. (Chris Hilton, After the Berlin Wall, 2011)

Chris Hilton

However you viewed it, The Wall made the city not just unique but completely abnormal. [...] Nobody knew how much the forty years had moulded East and West in separate ways, or even whether there was still a common German identity [...] Quietly in the background, hesitantly, carrying inescapable prejudices and preconceptions, the citizens of the two Germanys reached towards each other. Far from immediate satisfaction for the unleashed desires, ordinary people began to speak of it lasting generations. (Chris Hilton, After the Berlin Wall, 2011)

Further reading on Perlego

30 Years since the Fall of the Berlin Wall (2020) edited by Alexandr Akimov and Gennadi Kazakevitch

After the Berlin Wall: Germany and Beyond (2011) edited by Katherine Gerstenberger and Jana Evans Braziel

Checkpoint Charlie: The Cold War, The Berlin Wall, and the Most Dangerous Place On Earth (2019) by Iain MacGregor

The History of the Stasi (2014) by Jens Gieseke

Berlin Wall FAQs

What was the Berlin Wall?

What was the Berlin Wall?

Why was the Berlin Wall built?

Why was the Berlin Wall built?

Why did the Berlin Wall come down?

Why did the Berlin Wall come down?

Bibliography

50Minutes (2017) The Fall of the Berlin Wall: The End of the Cold War and the Collapse of the Communist Regime. 50Minutes.com. Available at:

Bannock, C. (2014) “Berlin Wall – readers' memories: ‘It's hard to remember how scary the Wall was.’”The Guardian. Available at:

Bozo, F., Rödder, A., and Sarotte, M. E. (eds) (2016) German Reunification: A Multinational History. Routledge. Available at:

https://www.perlego.com/book/1634657/german-reunification-a-multinational-history

Corner, L. (2009) “The Berlin Wall kept me apart from my baby son.” The Guardian. Available at:

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2009/nov/07/berlin-wall-sigrid-paul

Evans, S. (2011) “The Berlin Wall sickness that still lingers today,” BBC. Available at:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-14488681

Frye, D. (2018) Walls: A History of Civilization in Blood and Brick. Scribner. Available at:

https://www.perlego.com/book/1391075/walls-a-history-of-civilization-in-blood-and-brick

Gassert, P. and Steinweis, A. E. (2006) Coping with the Nazi Past: West German Debates on Nazism and Generational Conflict, 1955-1975. Berghahn Books. Available at:

Graham-Dixon, F. (2013) The Allied Occupation of Germany: The Refugee Crisis, Denazification and the Path to Reconstruction. I. B. Tauris. Available at:

Mensch, C. (2009) Modern Art and the Berlin Wall: Demarcating Culture in the Cold War Germanys. I. B. Tauris. Available at:

Meyer, M. (2010)1989: The Year that Changed the World: The Untold Story Behind the Fall of the Berlin Wall. Simon & Schuster UK. Available at:

Miller, B. (2022) The Stasi Files Unveiled: Guilt and Compliance in a Unified Germany. Routledge. Available at:

Miller, B. (2002) Narratives of Guilt and Compliance in Unified Germany: Stasi Informers and their Impact on Society. Routledge. Available at:

Noir, T. [2024] “The Berlin Wall.” Noir. Available at:

https://thierrynoir.com/biography/essays/berlin-wall/

Rottman, G. L. (2012) The Berlin Wall and the Intra-German Border 1961-89. Osprey Publishing. Available at:

https://www.perlego.com/book/3766843/the-berlin-wall-and-the-intragerman-border-196189

Schweizer, P. (2019) “The Fall of the Berlin Wall after Ten Years,” in Schweizer, P. (ed.) The Fall of the Berlin Wall: Reassessing the Causes and Consequences of the End of the Cold War. Hoover Institution Press. Available at:

West Brett, D. (2015) Photography and Place: Seeing and Not Seeing Germany After 1945. Routledge. Available at:

https://www.perlego.com/book/1644101/photography-and-place-seeing-and-not-seeing-germany-after-1945

Wilke, M. (2014) The Path to the Berlin Wall: Critical Stages in the History of Divided Germany. Berghahn Books. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/540452/the-path-to-the-berlin-wall-critical-stages-in-the-history-of-divided-germany

Willis, J. (2013) Daily Life Behind the Iron Curtain. Greenwood. Available at:

https://www.perlego.com/book/4183541/daily-life-behind-the-iron-curtain

Varon, J. (2004) Bringing the War Home. University of California Press. Available at:

https://www.perlego.com/book/551939/bringing-the-war-home

Zachau, R. and Apgar, R. (2022) Hidden Berlin: A Student Guide to Berlin's History and Memory Culture. Hackett Publishing Company Inc. Available at:

PhD, English Literature (Lancaster University)

Sophie Raine has a PhD from Lancaster University. Her work focuses on penny dreadfuls and urban spaces. Her previous publications have been featured in VPFA (2019; 2022) and the Palgrave Handbook for Steam Age Gothic (2021) and her co-edited collection Penny Dreadfuls and the Gothic was released in 2023 with University of Wales Press.